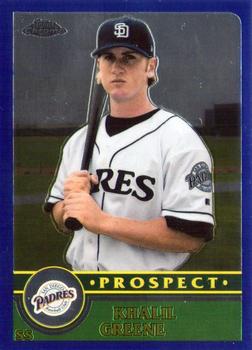

Khalil Greene

Khalil Greene’s performance in youth and collegiate ball was a showcase of abundant talent. The shortstop’s senior year at Clemson University in 2002 bespoke Hall of Fame ability. Less than two years later, Greene ascended to the majors. He had apparently begun to fully realize his huge promise at the top level in 2007.

Khalil Greene’s performance in youth and collegiate ball was a showcase of abundant talent. The shortstop’s senior year at Clemson University in 2002 bespoke Hall of Fame ability. Less than two years later, Greene ascended to the majors. He had apparently begun to fully realize his huge promise at the top level in 2007.

Yet despite the remarkable skill that Greene exhibited on the diamond, he faced an adversary he could not conquer: social anxiety disorder. His trademark cascading blond locks and serene disposition were reminiscent of a laid-back surfer – but Greene was grappling with extreme, self-imposed pressure. In 2010, still just 30, he quit baseball and retreated into deep privacy. His rise to the pinnacle of professional baseball attested to his skill – but his subsequent fall resonates even more profoundly.

Khalil Thabit Greene was born on October 21, 1979, in Butler, Pennsylvania (35 miles north of Pittsburgh). His parents were James and Janet (née Croskey) Greene. Khalil was the middle child of three, coming between daughters Anisa and Lua.1

James, a former Marine, grew up in the Lutheran Church. However, he found himself “searching for something more” spiritually upon his return from Vietnam.2 This ultimately led James and Janet (then still his wife-to-be) to embrace the Baha’i Faith.3 For Jim, the most appealing part of this religion was its unwavering commitment to achieving peaceful conflict resolution.4 As a show of their commitment to Bahá’í, James and Janet named their only son “Khalil,” which means “friend of God” in Arabic.5 Thabit, his middle name, means “steadfast.”6 Decades later, when asked about the origins of his name, the shortstop replied, “I think my dad said in an interview one time that he named me that because he felt that if I could live up to that title that I’d be doing fairly well for myself.”7

Khalil’s sisters were also named in accord with the teachings of the Bahá’í Faith. Anisa carries the meaning “Tree of Life.”8 Lua also has significance in the faith – a woman named Louise “Lua” Getsinger was one of its early proponents in the U.S. Janet considered training her children in Baha’i teachings of primary importance.9

Jim remembered his son wielding a Wiffle ball bat in the living room as a toddler – a first step on young Greene’s path to eventual stardom.10 However, that memory was accompanied by one of an eight-year-old Khalil reciting prayers from memory with the voice of “a believer.” As Jim described it, “We’ve always had the feeling he’s an old soul. An old man from a long time ago.”11

After Greene turned five, his family relocated to Key West. The move was reportedly prompted by a job opportunity that Jim received, although there’s still ambiguity regarding the exact nature of both parents’ professions. Various sources have depicted Jim as a jeweler, artist, and woodworker. A 2011 article noted that he was a graduate of the Art Institute of Pittsburgh and a sculptor whose chief inspiration was Baha’i themes and influences.12 Janet primarily has been characterized as an elementary school teacher, although one account also suggested her involvement in jewelry.13

Although Khalil Greene initially found comfort in soccer, his passion soon turned to baseball. When asked by a grade-school teacher what he wanted to do when he grew up, Greene replied “play baseball,” to which the teacher responded, “You need a backup plan.”14 However, Greene did not have one; Janet too knew her son was born to play baseball, saying, “There was no second choice, there never has been.”15

Greene went to Key West High School, where he became the starting varsity shortstop midway through his sophomore season. The Conchs won the state championship that season. Former coach Ralph Henriquez Jr. recalled Greene as being “very, very quiet. He didn’t say much, just played very hard. You’ve heard of players who lead by example by the way they play? Khalil was one of those.”16

Brooks Carey, a former Triple-A pitcher, took over as head coach in Greene’s senior year. However, some years prior Carey had been a youth league umpire and first witnessed his future superstar, then only 11. “I was standing behind the pitcher’s mound calling balls and strikes,” Carey said. “A ball was hit in the hole at shortstop, and this kid made a major-league play. Then the kid got to the plate. I thought he might be the best player in America. You couldn’t really be any better than he was.”17

Greene and Carey led the Conchs to another state championship in 1998, the 10th in school history.18 That year Greene hit .500 with 54 RBIs, scored 50 runs, and stole 30 bases.19 Years later, Carey recalled one of his fonder memories from coaching Greene. “I played with Cal Ripken when he was 17 and 18 years old, and I thought Khalil had more talent than Cal. Cal used to get upset when I said that. So, during spring training, the Orioles had a day off and I asked Cal to come down and throw out the first pitch at one of our games and told him, ‘Watch the kid play. I don’t know what to tell you. He’s better than you.”20 Greene hit a mammoth home run in his first at-bat that game.

After graduating from high school, Greene had to decide whether to go to college or accept an offer from the St. Louis Cardinals that included a $250,000 signing bonus contingent upon his transition to catcher.21 The decision was made at a breakfast between Greene, Carey, and Cardinals’ scout Doug Carpenter. Carey recalled telling Carpenter, “You are going to ask him, and he is going to look at you and say no. He doesn’t talk in sentences. I never heard his voice until the middle of the season when I went out to shortstop one day at practice and asked him a question.”22 Sure enough, after Carpenter made his offer, Greene replied with a simple “no thanks,” and kept eating.23

Every team passed on Greene in the draft that summer. Despite Carey’s plea to his former coach at Florida State University, Mike Martin, there was no spot for Greene in Tallahassee. However, Tim Corbin – currently Vanderbilt University’s head coach and then an assistant at Clemson – was impressed by Greene’s talent after seeing him for a second time at a high school showcase in Atlanta. “The more I saw him over the course of that week, the more I knew he was a really good player who could do a lot of different things,” Corbin said. “When he was at bat or had a ball hit to him, you would walk away thinking, ‘That’s the best player on the field.’”24 Clemson offered, and Greene accepted.

Greene enrolled at the South Carolina school in 1999; his roommate at the time, Kyle Frank, summed up the new kid as a “fish out of water.”25 As Frank explained, “I think he’s the type of guy that doesn’t really feel comfortable or confident until he establishes himself with baseball.”26

For the first time in his career, Greene found himself playing third base. He started in 68 out of 69 games and compiled a team-leading 98 hits, a Clemson freshman record.27 He also led the Tigers in multi-hit games (31) and at-bats (274), while hitting .358. Greene’s freshman year concluded with a unanimous selection to the All-Regional Team.28

Greene was known off the field for his eating habits. Intent on eating six meals a day, he would wrap chicken patties from the cafeteria in a napkin and bring them to the ballpark.29 Sometimes he even would carry a drumstick under his shirt or in his back pocket.30 Greene was “religious” about his meals, according to Clemson first baseman Mike Calitri, who recalled, “When somebody brings a pizza into the hotel room when we’re traveling, Khalil’s saying, ‘No, thank you. It’s not right.’”31 Greene never ate breakfast with the team, but head coach Jack Leggett never cared, saying, “I know he’s eating right and I know he’s not sleeping, so I’m fine with it because I’m not sure any kid I’ve ever had has the respect of his teammates as a baseball player as much as Khalil has.”32 Corbin often said of Greene: “He treats his body like it’s a newly bought Mercedes Benz.”33

His away-game outfits also got attention. Greene boarded airplanes dressed in white leisure suits, snakeskin cowboy boots, and a fur coat. “Unbelievable” was the only word Leggett could use to describe his superstar’s outfits.34

Greene’s bat continued to sizzle in his sophomore season. He hit .364, with five homers, 64 RBIs, an on-base percentage of .470, and a team-leading .444 average with runners in scoring position.35 During a weekend series against Florida State, then ranked No. 2 in the nation, Greene went 6-for-8 with five RBIs and collected the ACC Player-of-the-Week award.36

Greene spent that summer playing for Falmouth in the Cape Cod Baseball League. His coach with the Commodores, Jeff Trundy, admitted that most players he coached over the years followed daily routines, but Greene was “more dedicated to them than others. He’s very strict about it.”37

In his junior year, Greene returned to his best position – shortstop – and posted a fielding percentage of .965.38 He broke the previous school record of .950 set by Bill Spiers in 1987.39 Although Greene’s batting average was down from previous years, he still hit .303 and slugged .403 in 241 at-bats, including 12 dingers, two triples, and a team-high 18 doubles. Greene earned ACC Player of the Week honors in May after batting .412 with 10 RBIs.40 As the draft approached, baseball columnist Peter Gammons declared, “You won’t find Clemson shortstop/third baseman Khalil Greene or Wake Forest center fielder Cory Sullivan on any top-100 list but check back five years from now and see if they aren’t remarkably like Jeff Cirillo and Steve Finley.”41 Greene fell to the 14th round, 408 overall, to the Chicago Cubs. He did not sign.

Greene’s senior season was extraordinary. In 285 at-bats, he accumulated 134 hits, including 27 homers, for a .470 batting average. He drove in 91 runs while scoring 93 and struck out only 22 times. These stats were complemented by a .552 on-base percentage and an .877 slugging percentage. His .967 fielding percentage surpassed the record he had set the preceding season.42 Greene won ACC Player of the Week honors three times.43 He concluded his journey at Doug Kingsmore Stadium with a memorable home run in his final at-bat.44 The Tigers made it to the College World Series, only to fall to South Carolina in the semifinals.

After the season’s conclusion, Greene reflected on his time in a Tiger uniform. “I want to be remembered for being consistent more than anything else,” he said. “For me, that means a lot more than the records do. There are a lot of guys that probably could have played that much. But they might not have put up the numbers to stay there.”45

That summer, USA Baseball announced that Greene had been named the recipient of the 2002 Golden Spikes Award.46 Upon receiving the news, he remarked, “I wanted to go out and play every game as hard as I could this season, with it being my last year in college. To be able to look back on the year and know that I was named the best amateur player as the Golden Spikes Award winner, it’s just a very special honor.”47

Greene took home various other awards after the season ended, including:

- National Player of the Year, as named by Collegiate Baseball48

- ACC Player of the Year49

- Louisville Slugger NCAA Division I All-American50

- Baseball America College Player of the Year

- The Rotary Smith Award

- The Dick Howser Award

His name remains listed multiple times in the Division I baseball record book, most notably for:

- 134 hits in a single season (tied for fifth all-time)

- 250 total bases in a single season (tied for sixth)

- 1,069 career at-bats (sixth)

- 403 career hits (second)

- 668 career total bases (fourth)

- 726 career assists (fourth)

- 95 career doubles (leader)

Greene graduated that spring with a degree in sociology. He earned All-Conference Academic Honors three consecutive years.51 In one final “tip of the cap” to Greene’s collegiate career, he received a special resolution from the South Carolina General Assembly.52

Reflecting on Greene’s senior season at Clemson, Leggett stated, “The year he had was the best I have ever seen. He was always very private and quiet, but when it came time to play, he was always ready, he always had the right frame of mind.”53 Leggett continued, “He was very disciplined off the field and very regimented in what he ate. He ate tuna fish right out of the can and ate oatmeal for breakfast every morning. He just marched to his own drum. But all of his teammates would probably tell you he was the best player they ever played with.”54

Years later, after being inducted into the Clemson Ring of Honor, Greene’s name was etched in the outfield wall in Doug Kingsmore Stadium, where it remains today.55

The San Diego Padres selected Greene with the 13th overall pick in the 2002 major-league draft, then paid him a $1.5 million signing bonus.56 He was dispatched to Low-A Eugene, but after just 37 at-bats won promotion to High-A Lake Elsinore.57

In 2003, Baseball America ranked Greene as the team’s No. 2 prospect and stated, “All of Greene’s tools are average or better, and he supplements them with excellent instincts. His bat speed, hand-eye coordination, pitch recognition and ability to adjust make him the best pure hitter in the system. He also has surprising power for his size. Scouts question whether he’s a pure shortstop, but his hands, range, arm, first-step quickness, and body control are all assets.”58

The following year Greene opened with Double-A Mobile and then quickly elevated to Triple-A Portland. After just 319 at-bats in Triple-A, Greene was on his way to Petco Park.59 He was the first position player from the 2002 draft to reach the majors.60

Baseball America kept Greene ranked as the No. 2 prospect in the organization, but Baseball Prospectus had a different take: “The Padres rushed Greene, who was just getting by at Double-A, through two levels last year and had him at Qualcomm just 15 months after draft day. A short, muscular player [5-feet-11 and 210 pounds] with decent power potential, Greene hasn’t shown the plate discipline as a pro that helped him become the 13th pick in the 2000 draft.”61

Greene remained steadfast and open in his dedication to the Baháʼí Faith upon reaching the major leagues. He told The Portland Tribune in 2003, “We believe in Jesus Christ, (prophet) Mohammed and Moses and all their writings, but further it with the Baha Allah, who came to preach the faith as a manifestation of God. It’s not pacifism.”62 He added that the Baháʼí Faith declares “oneness of mankind, equality of gender and races,” as well as “a progression of revelations and religions.”63

The following year, Greene revealed that reliance on his faith had grown since his debut. He remarked, “There are so many things you can apply it to in terms of handling failure, handling success, dealing with any type of pressure that is applied, whether it be by others, by yourself.”64 Although Greene acknowledged the importance of the sport, he consistently endeavored to adhere to the teachings of his faith. “If I accept the fact that what I do brings happiness to people and they enjoy watching me play, then I feel that in itself is a form of worship. We’re taught in (the Baháʼí) faith that your work can be a form of worship. I try to do that and play the game like it’s meant to be played.”65 Greene began reciting a particular prayer at the ballpark that commences with “Bear witness, oh my God, that thou has created me to know thee and to worship thee.”66 Greene always felt a sense of joy and pride when others said of him, “He’s a Baháʼí.”67

After getting his feet wet with 20 games for the Padres in 2003, Greene hit .273 (132-for-484), with 15 home runs in 2004. He finished second in the National Rookie of the Year voting.

The next year Greene began to struggle at the plate, which would intensify over time. In 436 at-bats in 2005, he hit .250 with a .296 on-base percentage. While his on-baseball percentage improved in 2006, his batting average and slugging percentage dropped. Despite Greene’s troubles at the plate, David Pinto’s Probabilistic Model of Range ranked him as the fourth-best defensive shortstop that season. John Dewan’s Fielding Bible also gave him a positive review: “Greene is a very good defender despite having only average range and arm for the position. He has superb instincts, always positions himself well and has a quick release that makes up for his lack of arm strength. He is also very smooth turning double plays.”68

Some wondered if Greene’s poor performance stemmed from a series of injuries – a broken finger in 2004, fractured toe in 2005, and torn finger ligament in 2006.69 When asked about the injuries during spring training in 2007, Greene replied, “I don’t look at it as I’m unlucky or that this is unfortunate, I look at it as a test. There are things that happen to you – whether it’s in your profession or outside of your profession. Things happen for a reason, and it’s not for me to analyze it and find out a reason why. Sometimes it’s for you not to figure out, you’re not necessarily to know everything.”70

In 2007, Greene surged at the plate, hitting 27 home runs while driving in 97 runs and slugging .468. All were career highs. He set a new team record for fielding percentage at short of .984.71 His performance led to a two-year contract worth $11 million during the ensuing offseason.72

Greene was well-liked in the Padres clubhouse. His teammates frequently complimented him on his attitude; Phil Nevin said, “You just don’t see players of his age and experience come to the park as prepared as he does. He reminds me of Ripken, the way he works to recognize where the ball is in the strike zone and what the hitter’s swing is like.”73 In addition to his daily oatmeal and tuna diet, Greene was also known for writing his own hip-hop lyrics, wearing his uniform baggy, parting his blond hair down the middle.74 To Greene it was “all about the flow … fluidity of motion and thought.”75

After his career year in 2007, Greene struggled in 2008, hitting only .213 with 10 home runs and 15 doubles. His slugging percentage fell to .339, while his on base percentage dipped to .260. All were career lows. Greene’s 2008 season – and action as a Padre – ended in the seventh inning on July 30. He suffered a broken hand punching a storage cabinet after his 100th strikeout of the season.76

That offseason, San Diego traded Greene to the St. Louis Cardinals. On the day of the trade, former Padres’ manager Bud Black said, “One of the things that people don’t really see is how he internalizes so much. He doesn’t let it out, but he’s a player who cares a great deal about his performance, to the point where it gets to him. I wish he would let go and enjoy how good he is. But for whatever reason, he can’t do it.”77

Initially, a change of environment revitalized Greene’s performance. During spring training, Greene hit .408 and drove in 17 runs, prompting manager Tony La Russa to bat him cleanup on opening day.78 However, despite his hot exhibition season, he hit only .219 in April and .171 in May.79

Later that month Greene was placed on the disabled list because of social anxiety disorder. A St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter, the late Joe Strauss, reported that Greene’s disorder was “brought on by fatigue caused by incessant stress.” Strauss added, “Any failure, such as a strikeout or an error, reinforces a sense of frustration that finds release only through verbal or physical outbursts, followed by embarrassment and regret.”80

Teammates soon noticed Greene “punishing himself,” to which he responded, “It’s the only way I can get it out.”81 Greene later admitted to “cutting himself in mental anguish.”82

Reinstated by St. Louis on June 18, Greene struck out in his only at-bat as a pinch-hitter in his first game back. He then homered in each of the next three games.83 However, 11 days later, Greene returned to the disabled list as his anxiety resurfaced. Greene returned to the team August 2 and played sporadically throughout the month as a pinch-hitter and third baseman. On August 28, Greene, as an eighth-inning pinch-hitter, blasted a home run to tie the game against the Washington Nationals. It was the first pinch-hit homer of his big-league career. During his sole season in St. Louis, Greene managed just 193 plate appearances and had a career-low .200 batting average.

After becoming a free agent, Greene signed a one-year, $750,000 contract with the Texas Rangers in January 2010.84 However, his contract was voided the next month after he was unable to report to spring training. Greene’s agent, Mike Milchin, cited “recurrence of issues he’s dealt with in the past.”85

Greene’s career ended after seven seasons. His final stats in 736 games played: 2,567 at-bats, 628 hits, 352 RBIs, 90 home runs, and 556 strikeouts. He earned an estimated $14.3 million during his career.86

In 2018, Rob Rains, editor of STLSportsPage.com, sought out Greene in hopes of gaining some perspective on his life after retirement. Unfortunately, despite numerous interview requests, no successful contact was made with him. However, Rains did eventually find that as of 2018, Greene resided in Greer, South Carolina, alongside his wife Candice (née Cole, married November 18, 2006) and their two sons. While Rains was not able to speak to Greene directly, he did speak with a handful of his former teammates and coaches.

Mark Loretta, a former teammate with the Padres, expressed only “fond memories of playing with him and knowing him.”87

Cardinal Adam Wainwright echoed that sentiment, remarking, “I thought he was a great guy, a great teammate. He was extremely sneaky funny with a very dry humor.”88 Wainwright did mention that one time Greene told him, “When I get done with baseball, you will probably never see me or hear of me again.”89

Former teammate Skip Schumaker also voiced his admiration for Greene’s abilities, yet provided insight into the emotional turmoil Greene was experiencing. “He really cared about baseball and really wanted to perform well, and when it didn’t happen, he didn’t know what else to do except hurt himself. It was sad to watch and witness. He would just get really frustrated and not know how to react or show it without hurting himself a little bit.”90

Not even Jack Leggett has been able to connect with his former shortstop. “I’ve tried to reach out and leave messages,” said the coach, “but I don’t know if they are being heard or not. At one point I talked to his parents (who also live in Greer) a while back. I always had a soft spot in my heart for him. I love Khalil, and I love what he has done for our program. All the memories and thoughts I have of him are positive.”91

According to Rains, the only person who still maintains a relationship with Greene is Corbin, because their wives are friends. As Corbin says it, “I give him space. Unless you reach out to him, he is not going to bother you. He has kids now, and he is just kind of doing his thing. I get a general idea of how he’s doing. I do want to pick up and get with him again. I guess life just moves on, and you get distracted with a lot of different things. It’s not because I don’t think about him. I love him as a person, and I love what he’s about. He’s a special kid.”92

Unless he should someday reemerge in the public eye, Khalil Greene’s narrative will forever be framed by his personal trials. One may contemplate the extent to which these challenges reshaped the trajectory of a career that held brilliant passages with just a fraction of his promise realized.

Last revised: October 30, 2023

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Mike Eisenbath and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Photo credit: Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com, thebaseballcube.com, baseball-almanac.com, NCAA Division I Baseball Records, 2019 (http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/stats/baseball_RB/2021/D1.pdf), and ancientfaces,com (wedding date).

Notes

1 Dan Patrick, “Dan Patrick turns two with Khalil Greene,” ESPN.com, April 11, 2005 (https://africa.espn.com/espn/magazine/archives/news/story?page=magazine-20050411-article50).

2 Eric Neel and Tim Kurkjian, “Deep Short | Cheap Relief,” ESPN.com, July 10, 2012 (https://www.espn.co.uk/espn/magazine/archives/news/story?page=magazine-20040621-article31).

3 Neel and Kurkjian, “Deep Short | Cheap Relief.”

4 Neel and Kurkjian, “Deep Short | Cheap Relief.”

5 Jon Solomon, “Shades of Greene: Clemson Shortstop Khalil Greene Is One of College Baseball’s Best Players and Maybe Its Most Unique,” Anderson (South Carolina) Independent-Mail, May 30, 2002. Accessed via Baha’i Library Online, (https://bahai-library.com/newspapers/2002/020530.html).

6 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

7 Sandi Dolbee, “Passion for Game, Faith Drives Padres’ Greene,” Religious Forums, November 16, 2004 (https://www.religiousforums.com/threads/passion-for-game-faith-drives-padres-greene.5614/).

8 Virginia Miller, “Callery woman seeks U.N. support of Baha’i,” North Hills (Pennsylvania) News Record, February 5, 1982: 4. David Langness, “The Anisa Project: A Baha’i-Inspired Educational Model,” BahaiTeachings.org, April 12, 2016 (https://bahaiteachings.org/anisa-project-bahai-inspired-educational-model/).

9 Miller, “Callery woman seeks U.N. support of Baha’i.”

10Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

11 Neel and Kurkjian, “Deep Short | Cheap Relief.”

12 Robin Edgar, “Nature-inspired mixed media: James G. Greene,” Tryon (North Carolina) Dailly Bulletin, April 27, 2011 (https://www.tryondailybulletin.com/2011/04/27/nature-inspired-mixed-media-james-g-greene/)

13 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

14 Rob Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?” News from Rob Rains, STLSportsPage.com, January 25, 2019 (https://stlsportspage.com/2018/11/09/whatever-happened-to-former-cardinals-infielder-khalil-greene/).

15 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

16 Ralph Morrow, “Sports & Mental Health: First Khalil, Now Simone,” Florida Keys Weekly Newspapers, August 6, 2021 (https://keysweekly.com/42/sports-mental-health-first-khalil-now-simone/).

17 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

18 Key West Conch Baseball, May 7, 2020 (https://www.facebook.com/KwPrepLeague/photos/a.523995610995456/3109755069086151/?type=3).

19 Key West Conch Baseball.

20 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

21 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

22 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

23 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

24 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

25 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

26 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

27 JP Priester, “Clemson Baseball: Remembering Khalil Greene,” Sports Illustrated, April 18, 2020 (https://www.si.com/college/clemson/baseball/khalil-greene-clemson-ring-of-honor).

28 Priester, “Clemson Baseball: Remembering Khalil Greene.”

29 David Harry, “Khalil Greene: Anything but Average,” TigerNet.com, May 24, 2000, (https://www.tigernet.com/clemson-baseball/story/khalil-greene-anything-but-average-497).

30 Harry, “Khalil Greene: Anything but Average.”

31 Harry, “Khalil Greene: Anything but Average.”

32 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

33 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

34 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

35 Priester, “Clemson Baseball: Remembering Khalil Greene.”

36 “Clemson Baseball Hosts Florida State in Tigertown This Weekend,” Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site, May 3, 2000. ( https://clemsontigers.com/clemson-baseball-hosts-florida-state-in-tigertown-this-weekend/). “Baseball’s Khalil Greene Named ACC Player-of-the-Week,” Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site, May 8, 2000 (https://clemsontigers.com/baseballs-khalil-greene-named-acc-player-of-the-week/).

37 Neel and Kurkjian, “Deep Short | Cheap Relief.”

38 “Baseball Team Names Four Captains for 2002,” Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site, November 8, 2001 (https://clemsontigers.com/baseball-team-names-four-captains-for-2002/).

39 “Baseball Team Names Four Captains for 2002.”

40 “Steve Reba and Khalil Greene Share Weekly ACC Honors,” Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site, May 14, 2001 (https://clemsontigers.com/steve-reba-and-khalil-greene-share-weekly-acc-honors/).

41 Peter Gammons, “Baseball Draft so Unpredictable,” ESPN.com, June 2, 2001 (http://www.espn.com/gammons/s/2001/0602/1208718.html).

42 Priester, “Clemson Baseball: Remembering Khalil Greene.”

43 “Khalil Greene Named ACC Co-Player-of-the-Week,” Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site, May 6, 2002, (https://clemsontigers.com/khalil-greene-named-acc-co-player-of-the-week-2/#:~:text=He%20is%20the%20only%20player,for%2D16%20in%20five%20games).

44 Priester, “Clemson Baseball: Remembering Khalil Greene.”

45 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

46 “Khalil Greene Wins Golden Spike Award,” Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site, July 9, 2002, (https://clemsontigers.com/khalil-greene-wins-golden-spike-award/).

47 “Khalil Greene Wins Golden Spike Award.”

48 “Khalil Greene Wins Golden Spike Award.”

49 “Khalil Greene Wins Golden Spike Award.”

50 “Khalil Greene Wins Golden Spike Award.”

51 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

52 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

53 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

54 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

55 Priester, “Clemson Baseball: Remembering Khalil Greene.”

56 “Khalil Greene Stats & Scouting Report,” College Baseball, MLB Draft, Prospects – Baseball America, August 24, 2023 (https://www.baseballamerica.com/players/11715-khalil-greene/).

57 “Khalil Greene Player Card,” Baseball Prospectus, accessed August 25, 2023 (https://www.baseballprospectus.com/player/31525/khalil-greene/).

58 “Khalil Greene Player Card,” Baseball Prospectus.

59 Marc Normandin, “Player Profile: Khalil Greene,” Baseball Prospectus, April 25, 2007 (https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/6148/player-profile-khalil-greene/).

60 Normandin, “Player Profile: Khalil Greene.”

61 Normandin, “Player Profile: Khalil Greene.”

62 Jason Vondersmith, “Not Your Everyday Baseball Player,” Portland (Oregon) Tribune, August 1, 2003. Accessed via Baha’i News (https://bahai-library.com/newspapers/2003/030801-1.html).

63 Vondersmith, “Not Your Everyday Baseball Player.”

64 Dolbee, “Passion for Game, Faith Drives Padres’ Greene.”

65 Dolbee, “Passion for Game, Faith Drives Padres’ Greene.”

66 Dolbee, “Passion for Game, Faith Drives Padres’ Greene.”

67 Solomon, “Shades of Greene.”

68 “Khalil Greene Player Card,” Baseball Prospectus.

69 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

70 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

71 “Padres, Greene Nearing Two-Year, $11 Million Deal,” ESPN.com, February 2, 2008, (https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=3227810).

72 “Padres, Greene Nearing Two-Year, $11 Million Deal.”

73 Neel and Kurkjian, “Deep Short | Cheap Relief.”

74 Neel and Kurkjian, “Deep Short | Cheap Relief.”

75 Neel and Kurkjian, “Deep Short | Cheap Relief.”

76 “Khalil Greene a Bench Player for Now,” ESPN.com, May 20, 2009 (https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=4188392).

77 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

78 “Khalil Greene: A Season on the Brink with Cardinals,” RetroSimba, December 5, 2018, (https://retrosimba.com/2018/12/05/khalil-greene-a-season-on-the-brink-with-cardinals/).

79 “Khalil Greene: A Season on the Brink with Cardinals.”

80 “Khalil Greene: A Season on the Brink with Cardinals.”

81 Justin Hulsey, “Report: Cardinals’ Khalil Greene might be cutting himself,” Bleacher Report, May 27, 2009, (https://bleacherreport.com/articles/184898-khalil-greene-cuts-himself).

82 Rick Scuteri, “Before Fernando Tatis Jr., We Had Khalil Greene,” audacy.com, January 10, 2020 (https://www.audacy.com/973thefansd/blogs/alex-perlin/before-fernando-tatis-jr-we-had-khalil-greene).

83 “Khalil Greene: A Season on the Brink with Cardinals.”

84 Richard Durrett, “Rangers Void Contract of IF Greene,” ESPN.com, February 25, 2010, (https://www.espn.com/dallas/mlb/news/story?id=4946015).

85 Durrett, “Rangers Void Contract of IF Greene.”

86 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

87 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

88 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

89 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

90 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

91 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

92 Rains, “Whatever Happened to Former Cardinals Infielder Khalil Greene?”

Full Name

Khalil Thabit Greene

Born

October 21, 1979 at Butler, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.