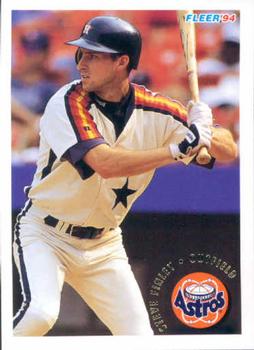

Steve Finley

Statistically, a 13th-round draft pick is highly unlikely to see the majors at all; even fewer go on to make two All-Star Game appearances or win five Gold Gloves and a World Series championship. Very few four-year college outfielders who debut in the majors at age 24 go on to have 19-year careers in which they accumulate over 2,500 hits. And almost no speed-and-defense center fielders wind up with over 300 career home runs. But Steve Finley managed all of those things en route to one of the more improbable careers of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Statistically, a 13th-round draft pick is highly unlikely to see the majors at all; even fewer go on to make two All-Star Game appearances or win five Gold Gloves and a World Series championship. Very few four-year college outfielders who debut in the majors at age 24 go on to have 19-year careers in which they accumulate over 2,500 hits. And almost no speed-and-defense center fielders wind up with over 300 career home runs. But Steve Finley managed all of those things en route to one of the more improbable careers of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Steven Allen Finley was born on March 12, 1965, in Union City, Tennessee. His parents, Fran and Howard, worked in education, and found jobs in the Paducah School District in Paducah, Kentucky, where Steve would grow up and become a baseball standout at Paducah Tilghman High. The only major-league baseball game Finley attended as a child —and, as of late 2017, one of only two he has ever attended as a fan —was Game Seven of the 1982 World Series at Busch Stadium, where, as a Tilghman High senior, he’d have seen Joaquin Andujar, Lonnie and Ozzie Smith, and Keith Hernandez lead the hometown Cardinals to a game and Series victory over Robin Yount and Paul Molitor’s Brewers.1

Finley attended Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois (an hour’s drive north of Paducah), impressed by coach Richard “Itch” (sometimes “Itchy”) Jones and the promise of a chance to compete for the starting job in center field from the outset. He won the center-field job in his freshman year, and with his excellence in hitting, speed, and defense, became perhaps the best all-around player the school has ever seen.

The Atlanta Braves drafted Finley in the 11th round in 1986, after his junior year, but Finley elected not to sign. Although having two parents in education was certainly a factor, it was breaking his leg in a summer league after his freshman year at SIU that really made the decision for him; in 1989, his mother told Ken Rosenthal: “He learned from that experience that nothing is a sure thing, that in a moment your life can change.” Finley returned for his senior year and completed a degree in physiology, after which —true to that goal of keeping his future options open —he was accepted into chiropractic school.2

Also in 1986, Finley was also selected to play for the American collegiate national team. It was a year that lacked the glamour of the Olympic teams of 1984 (which famously featured Will Clark, Barry Larkin, and Mark McGwire, among others) or 1988 (Jim Abbott, Ben McDonald, and Robin Ventura), but nonetheless gave Finley the opportunity to represent his country in the Netherlands in the Amateur World Series (whose name was changed to the Baseball World Cup the following year), along with future major leaguers including Scott Servais, Mike Remlinger, and Dave Hollins, and coached by legendary Fresno State coach Bob Bennett. Team USA finished 7-4 in the tournament and in fourth place, behind Cuba, South Korea, and Chinese Taipei.3

Finley had a successful senior year at SIU, wrapping up his career as the Salukis’ all-time leader in numerous offensive categories.4 Yet, he saw his draft stock slip from the year before —perhaps, as Rosenthal suggested in his 1989 profile, because teams questioned his commitment to the game after he chose not to sign a year earlier. Whatever the reason, the Baltimore Orioles selected him in the 13th round of the 1987 June draft —325th overall, 57 spots later than the Braves had picked him in ‘86.

This time, of course, Finley did sign. He reported to short-season Newark (New York-Penn League), where he was nearly two years older than the average player, and excelled both there and in Class-A Hagerstown for the remainder of 1987, batting .303/.357/.429, with 24 extra-base hits in 315 plate appearances, and 33 steals in 40 tries.

Finley opened 1988 back in Hagerstown for his age-23 season, but as seasoned as he already was, spent just eight games there before getting a promotion to Double-A Charlotte, then played just 10 games there before he was promoted yet again, this time to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings. At Rochester, managed by future Orioles skipper Johnny Oates, Finley batted .314/.352/.419 in 120 games, contending for a batting title and being named International League Rookie of the Year while leading the Red Wings to the West Division title.5

Finley’s performance and meteoric rise through the minors had more than sufficed to put him on the Orioles’ radar for 1989. The 1988 Orioles were one of the worst teams of the era, opening their season by losing a league-record 21 straight on the way to a 54-107 finish, and as such were in need of a youth movement heading into 1989. Manager Frank Robinson (who had taken over for Cal Ripken Sr. just six games into that season-opening losing streak) had nearly an entire roster full of tough decisions to make, but one of the toughest was center field, where Finley was expected to compete with another young outfielder, Brady Anderson, who had been acquired from Boston, for the starting job.

The Finley-Anderson matchup was an interesting one, especially so because they were such remarkably similar players (but also because Finley and Anderson would become brothers-in-law6). Anderson is about 14 months older than Finley. Both hit and threw left-handed, and both were considered speed-and-defense outfielders with limited power potential, whose strengths as big leaguers (if any developed) would be getting on base and stealing bases. (And the similarities didn’t end in 1989, either; both would blossom as excellent leadoff hitters in 1991-92 and develop surprising power later in their careers.) Perhaps because they had such similar skill sets, Robinson expected the winner to emerge in spring training, while the loser —likely Finley, if only due to their relative ages —returned to Rochester for additional seasoning. They were joined in the competition by Mike Devereaux, a soon-to-be-26 outfielder acquired by the Orioles in mid-March from the Los Angeles Dodgers.7

Ultimately, though, each impressed in spring training, and Robinson kept all three. Anderson opened the season as the Orioles’ starting center fielder, and Finley started in right; in his major-league debut on Opening Day, April 3, Finley batted third, and flied out to right against Roger Clemens in his first at-bat, then injured himself fielding a Wade Boggs single in the fourth and was replaced by Joe Orsulak.

Finley went on the disabled list and didn’t play again for nearly three weeks. He got the start in right on his return on April 22, getting his first career hit, a bloop single off the Twins’ Freddie Toliver, in the third inning. He started in exactly half of the Orioles’ 84 games between April 22 and July 28, but on that date, a game the Orioles would win in 13 innings, Finley came out with an injury in the 11th and wasn’t able to return to the majors until September 2. He finished the year a disappointing .249/.298/.318 in 81 games. Meanwhile, led by Cal Ripken Jr., Mickey Tettleton, and Randy Milligan, and with strong showings by Orsulak and Devereaux, the Orioles rebounded all the way to 87-75 and second in the American League East, earning Robinson both the BBWAA and The Sporting News’ Manager of the Year Awards.8

The 1990 season opened with Finley again penciled in as the Orioles’ starting right fielder, and while he moved around the outfield quite a bit, he stayed healthy, and got 513 plate appearances in 142 games, hitting a similarly uninspiring .256/.304/.328, with 22 steals in 31 attempts. The Orioles were unable to repeat their stunning success of 1989, however, falling to 76-85 and fifth place.

The Orioles and general manager Roland Hemond believed that the team’s chief problem was a lack of power; although Finley, Devereaux, Orsulak, and Anderson in the outfield and the Ripken brothers up the middle gave them one of the strongest defenses in baseball, and while the Orioles’ 129 home runs were slightly above the league average, they were led by Tettleton’s seemingly flukish 26 (he’d go on to be a power hitter for many more years, but he was 28 years old and his previous high had been 11), and only he and Ripken Jr. (21) topped 15. The thought was that the Orioles needed a big “run producer” in the middle of the lineup if they were going to be competitive again.

On January 10, 1991, Hemond got his guy: the Astros’ Glenn Davis, a star first baseman who had averaged nearly 30 home runs and 90 RBIs a year since 1986. In return, the Orioles sent the Astros 24-year-old starter Pete Harnisch, 24-year-old middle reliever Curt Schilling, and the 25-year-old Finley. Finley and Harnisch nonetheless joined their now-former Orioles teammates on a cruise later that month: “I’ve got the ticket in my hand,” Finley told a reporter. “I’d like to see them take it away from me now.”9

The Sporting News, in a capsule with no byline, immediately lauded the Orioles and panned the trade for the Astros. It began: “The Houston Astros, as we have previously known them, cease to exist.” The paragraphs analyzing the Astros’ side of the trade were titled “HONEY, I SHRUNK THE ASTROS” and accused the team of “shed[ding] every big salary on the roster in an effort to make the team attractive to buyers. The question is: Who will buy a ticket to watch this dreadful team? … [T]he Astros do not possess anyone resembling a major league first baseman. … At least Harnisch, a starter of some potential, and Schilling, a middle reliever, will help fill out a pitching staff reduced to rubble by free agency. Finley, a part-time starter in the Baltimore outfield, is a speedy singles hitter who should benefit from playing in the Astrodome. But who is going to drive in runs?” The capsule concluded: “Orioles fans should rejoice; Astros fans should revolt. … The Astros didn’t receive enough for a player of Davis’ magnitude and will be hard-pressed to win 60 games this season.”10

The writer’s immediate projection for the Astros wasn’t off by much; the ’91 squad went 65-97. But the trade, of course, was almost immediately recognized as a win for the Astros, and perhaps the worst in Baltimore franchise history. Davis suffered a freak injury in spring training in 1991, was never effective again, and was out of baseball by early 1993. (The Orioles had compounded their error by signing Davis to an extension that at the time was the richest contract in club history.)

Meanwhile, Harnisch immediately became the Astros’ staff ace, posting a 2.70 ERA in 216⅔ innings and earning an All-Star nod; Schilling continued to show some promise in 75⅔ innings of middle relief (though the Astros traded him to the Phillies at the opening of the following season for slightly younger reliever Jason Grimsley); and Finley blossomed into precisely the hitter the Orioles might have hoped he would become. In 159 games, Finley hit .285/.331/.406 (a well-above-average 113 OPS+), hit 10 triples along with 8 homers, and stole 34 bases (though he was caught 18 times as well). Finley’s 5.2 wins above replacement (WAR), per baseball-reference.com, led the team, just ahead of Rookie of the Year Jeff Bagwell, who’d decisively answered The Sporting News’ concern over first base.

Finley was even better in 1992; he hit .292/.355/.407, a 121 OPS+, and stole 44 bases in 53 tries. He again led the Astros in WAR at nearly 6, which, along with improvements from Bagwell, catcher-turned-second-baseman Craig Biggio, and third baseman Ken Caminiti, saw the Astros climb all the way back to 81-81. Finley, Bagwell, and Biggio each played in all 162 games, the first time three teammates had accomplished that feat together since the 1974 Phillies (Larry Bowa, Dave Cash, and Mike Schmidt).11 If there was a downside to Finley’s brilliant season, it was that he still wasn’t as valuable (5.7 WAR to 6.6) as rookie Kenny Lofton, whom the Astros had traded to Cleveland the previous December because he was stuck behind Finley. (So when Schilling was dealt in April of ’92, that made two young Hall of Fame-worthy talents the Astros had given up in four months, with very little to show for them.)

The Astros and new owner Drayton McLane avoided arbitration by signing Finley to a three-year, $10.4 million contract entering the 1993 season. Probably not coincidentally, Finley donated $250,000 that winter toward establishing a charitable youth fund to keep Houston-area children in school and off drugs, and an additional $20,000 worth of Astros tickets as incentives for the children in that program. But while the Astros would improve by four wins in 1993, they didn’t have Finley to thank for much of it, as he struggled to a .245/.301/.340 first-half line, and while he improved somewhat by batting .284 over the second half, he finished with just an 88 OPS+, missing 20 games along the way, mostly due to an injury in late April.

There were numerous rumors about the cash-strapped Astros trading Finley over the winter (along with Biggio, which is unthinkable in retrospect), but when Opening Day 1994 rolled around, Finley was still on the team, batting second and playing center field. He would rebound somewhat, missing another 20 games due to a mid-June injury and batting .276/.329/.424 in 94 games in the strike-shortened season —roughly league average —and setting a career high with 11 home runs.

The Astros took another huge step forward in ’94, thanks largely to Bagwell’s MVP-winning career year, and were on about a 93-win pace when that year’s players’ strike hit. But lower-than-expected attendance hit McLane’s pocketbook hard even before the strike eliminated nearly 50 games worth of revenue, and so on December 28, 1994, with the strike still unresolved, the Astros traded Finley to the Padres, in a remarkable 12-player deal, the highlights of which were Finley and Caminiti, two of the Astros’ higher-paid players, on Houston’s side and talented younger outfielder Derek Bell on San Diego’s.

The move seemed to revitalize Finley, who played all but five of the Padres’ 144 games in 1995 and batted a career-high .297, posted a 110 OPS+, scored over 100 runs for the first time in his career, hit double digits in home runs with 10 for only the second time, stole 36 bases at a 75 percent success rate, and won his first Gold Glove.

Finley never stole that many bases again, but also never hit as few as 10 homers again until he was 41 years old, as he went through one of the more startling transformations in baseball history between the 1995 and ’96 seasons. Batting in the number-two slot as usual (he’d slide down to third in the order in July, behind Tony Gwynn), Finley hit .318/.371/.598 in May after a bad April, and established a new career high with his 12th and 13th home runs on June 27, his 79th game. Finley credited Padres hitting coach Merv Rettenmund for his transformation.12

Finley finished the year batting .298/.354/.531, with 30 home runs, 126 runs scored, and 95 RBIs. Finley and NL MVP Caminiti presented a formidable 3-4 combo that combined for 70 home runs, and along with Gwynn led the Padres to a 91-71 record and first place in the NL West, the team’s first postseason since its 1984 World Series appearance. Finley went just 1-for-12 in the three-game Division Series sweep at the hands of the Cardinals.

The 1997 season was a letdown for the Padres, who fell back to fourth place, as all of those pieces save Gwynn (who, at 37, batted .372 in 149 games) took a step back. Finley nonetheless nearly matched his shocking 1996 home-run production, with 28, scored over 100 runs again, and stole 15 bases in 18 tries. Finley was named to his first All-Star team, replacing Barry Bonds in the field in the sixth inning and striking out against Randy Myers in his only at-bat.

Then 33, Finley may have seemed to be tailing off in 1998, at about the age that players with his skillset often do —while he played all but three of the Padres’ games and hit 40 doubles, he batted just .249 and dropped back down to 14 home runs, and, with a 90 OPS+, provided below-average offense for the first time in five years. The Padres had perhaps the best year in their history, however —driven by Vaughn’s 50 home runs and a stellar season by mercenary starter Kevin Brown —winning 98 games and their second NL West title in three years. After another poor NLDS, Finley was instrumental in the Padres’ NLCS victory over the Braves, batting .333 and drawing six walks in the six games, scoring three runs and driving in two. The Padres were then swept out of the World Series by the historically great, 114-win Yankees, Finley going 1-for-12 with a double.

After the season, Finley was a free agent, and although he expressed his preference to stay in San Diego, the expansion Arizona Diamondbacks, coming off a 97-loss inaugural season, were eager to bring in a winner, and went about it in a way that is almost never successful —luring in a slew of mid-30s free agents. They inked the 34-year-old Finley to a four-year, $21.5 million contract on December 18, 1998, a little less than three weeks after landing their real prize, a four-year, $52 million deal for Randy Johnson (35), and 10 days before they traded for Luis Gonzalez (31), Finley’s former Houston teammate. They joined inaugural-season Diamondbacks Jay Bell (33), Matt Williams (33), and Andy Benes (31) to form the core of a team that certainly looked better than the 1998 squad, but whose age left a lot of reason to be skeptical.

Instead, all of those players met or exceeded their perfect-world projections, as the Diamondbacks won a shocking 100 games and the NL West in just their second season. Finley rebounded to set a new high with 34 home runs (including three in one game on September 8 against the Brewers), and scored 100 runs while driving in 103 (yet didn’t lead the team in any of those categories). He won his second Gold Glove in center, and hit a brilliant .385/.500/.462 in the Division Series, though the Mets beat the D-Backs in four games.

It was around this time that baseball media and fans began seriously discussing the use of performance-enhancing drugs in baseball, and Finley (again like Brady Anderson) inevitably came up in those discussions. To be sure, with his late-career power surge, his unusual aging curve and spending several years as a teammate of admitted PED user Ken Caminiti, Finley’s career had several markers that people inclined to have such suspicions might find suspicious. At the same time, though, Finley’s power surges (like his brother-in-law’s in 1996) all came outside his contract years; indeed, 1998, his one big contract year, was one of the worst years of his career; he fell to 14 home runs after seasons of 30 and 28. So if he was using a substance and that substance gave him his sudden power, one questions his motive for apparently stopping that usage during the year in which he stood to make the most money. Also, Finley never displayed a noticeable change to his figure; pictures of him from 1990 look startlingly similar to ones from 2006. For his part, Finley has always strongly denied any such charges, and credited his transformation to coaching from Rettenmund and Gwynn that transformed his swing from a flat, slashing type of swing to one with a more upward arc, much as hitters two decades later began to discuss creating “launch angle.”13

The year 2000 saw the Diamondbacks slip by 15 games and into third place in the West, but Finley set a second straight career high in home runs with 35 (hitting his age in homers for the second straight year), putting up a .280/.361/.544 line and making his second career All-Star team, where he replaced Gary Sheffield in left in the seventh inning and got an RBI single off Mariano Rivera in the ninth in an unsuccessful NL comeback effort. That season also saw the Diamondbacks swing a five-player deadline deal with the Phillies that brought back Finley’s former underappreciated Orioles and Astros teammate turned superstar starter, Curt Schilling, which would set the stage for the most memorable year in franchise history.

But the 2001 Diamondbacks were a pitching-first team; only three regulars provided above-average offense by OPS+ (led by Gonzalez and his 57 home runs), and Finley was not one of the three, slipping back to 14 home runs and a .430 slugging percentage, for a 91 OPS+ in 140 games. But Johnson and Schilling finished first and second in the Cy Young Award voting, the team won 92 games and the West, and Finley dazzled throughout the postseason; in the NLDS against the Cardinals, he hit .421 with a double, and knocked in the only run with a single in Game One, permitting Schilling to outduel Matt Morris, 1-0, as the Diamondbacks went on to win in five games. In the NLCS, Finley again provided the offense behind a sterling pitching performance by Schilling, driving in three of the team’s five runs in a 5-1 win in Game Three, and then helped spark a big rally in their 11-4 Game Four win, as the Diamondbacks again won in five games. Finley then drove in two key runs in the Diamondbacks’ thrilling seven-game win over the Yankees in the World Series; Johnson and Schilling were named co-MVPs, but Finley may have been the series’ offensive MVP, batting .368/.478/.526 with a home run and five runs scored, and making an excellent running catch in Game Seven. In just their fourth year in existence, the Diamondbacks became the fastest expansion team to reach (and, of course, the fastest to win) the World Series. Finley has identified the world championship, as one might expect, as one of the major highlights of his career.14

One might reasonably have assumed again that despite his great postseason performance, Finley had entered a steep decline, having just finished his age-36 season with poor overall numbers. Instead, he again rebounded, playing 150 games for the 2002 Diamondbacks (who would win 98 games but be swept by the Cardinals in the NLDS, in which Finley was a nonfactor), hitting 25 home runs and putting up a 117 OPS+; in 2003 he added a virtually identical year to his 2002, except that with 10 triples (up from 2002’s four), he became the 17th player ever to reach double digits in his age-38 season or later, and the second ever (and first since 1922) to lead his league in that category.

The Diamondbacks were a team in decline, though, and when Schilling left Arizona for Boston via trade in November of 2003, it was clear that 2004 would be a tough season in Phoenix. When at the end of July Finley was as productive as ever (turning several of those triples into home runs, with 23 already), but the Diamondbacks were a staggering 33-72, they dealt Finley to the Dodgers. In LA, Finley continued hitting, and continued hitting home runs, adding another 13 to set another career high at 36 for the season, though none (in 2004, or his entire career) would be as important as his very last. On October 2, heading into the second-to-last game of the season, the Dodgers were 92-68 and at home to face the 90-70 Giants, a situation in which a win would clinch the NL West title. Brett Tomko had stymied the Dodgers for seven innings, then he and two relievers shut them down in the eighth, after which the Giants held onto a 3-0 lead. In the bottom of the ninth, though, a series of singles, walks, and a key error brought the game into a tie, and Finley came up against a fellow lefty, Wayne Franklin, with the bases loaded and one out. In almost exactly the moment every kid playing baseball in his or her backyard dreams of, Finley took an 0-and-1 pitch out to deep right-center —a walk-off, pennant-clinching grand slam. Finley has, unsurprisingly, named this as the top individual moment of his career.15 The Dodgers fell to St. Louis in the NLDS —the fourth time in Finley’s career that he had faced the Cardinals in that round of the postseason, and his team’s third loss —as Finley went 2-for-16.

Finley signed as a free agent with the Angels for the 2005 season, and served as the primary center fielder for a team that made it to the American League Championship Series, in his age-40 season. It was the worst of his career offensively, at just a 71 OPS+, but he played 112 games and continued to start for the Angels through the postseason.

Finley was traded to the Giants for his age-41 season, and had something of a comeback, though his overall offense was still well below average, at an 83 OPS+. He did hit 12 triples (in a year in which Lofton and Finley’s Giants teammate Omar Vizquel joined him in that exclusive club of players who’d hit 10 triples or more at age 38 or later), making him only the second player in his 40s to reach double digits, along with Honus Wagner. His 300th home run came on June 14, leading off the game against Claudio Vargas back at his old home park in Arizona.

Finally, just before spring training and two weeks before his 42nd birthday, Finley signed with the Colorado Rockies, making him and reliever Matt Herges (who also signed with the Rockies that season) the first two, and (through 2018) the only players to have played for all five teams in the National League West. But while the Rockies would ultimately advance to the World Series, Finley simply didn’t have it anymore, drawing his release on June 13 after hitting just .181/.245/.245 in 43 games. He retired with a batting line of .271/.332/.442 and a 104 OPS+. With 44.3 WAR per baseball-reference, Finley sits (as of 2018) just outside the all-time top 400, in the same neighborhood as such very-good-but-not-quite-Hall-worthy outfielders as Rocky Colavito, George Foster, and Al Oliver. With 304 home runs and 320 stolen bases, Finley remains one of just eight players all time with more than 300 in both categories (joined by two of his former teammates, Reggie Sanders and Barry Bonds). Finley appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot in 2013, but got just four votes and fell off the ballot.

Finley returned to San Diego after his retirement, and has had various roles with the team’s broadcasting crews and the team itself; as of at least 2017, he was the Padres’ player development special assistant.16 Finley is also a registered broker/dealer with Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC, focusing on helping professional athletes manage their money with Morgan Stanley’s Global Sports and Entertainment Group.17 He has also made an (unsuccessful) foray into the restaurant world.18 After divorcing his first wife, Amy Jantzen Finley, to whom he was married from 1992 until 2008, Finley married Meaghan Hunt in June 2012.19 Finley has five children, one of whom, Austin Finley, became a professional surfer.20

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Steven Kutz, “Former All-Star Steve Finley on Helping Today’s Players Be Smart with Money,” MarketWatch.com, November 5, 2017. marketwatch.com/story/steve-finley-who-played-for-both-the-dodgers-and-astros-shares-what-its-like-to-play-in-a-world-series-2017-10-27.

2 Ken Rosenthal, “The Meteoric Rise of Oriole Steve Finley,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 3, 1989. articles.latimes.com/1989-05-03/sports/sp-2565_1_charlie-finley-oriole-steve-finley-orioles-manager-frank-robinson.

3 usabaseball.com/team-usa/collegiate-national-team/history.

4 siusalukis.com/hof.aspx?hof=67; Southern Illinois Salukis 2017 baseball media guide, available at siusalukis.com/documents/2017/2/15//2017_BSB_Media_Guide_spreads_small.pdf?id=6133.

5 “Around The Minors,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1988: 39.

6 The relationship is mentioned on both players’ Baseball-Reference pages and in numerous other online sources, but it isn’t clear where in their families the connection was formed.

7 “A.L. East,” The Sporting News, March 27, 1989: 31.

8 The Sporting News, November 13, 1989: 57.

9 “David Trade Opens Door for Tolentino,” The Sporting News, January 28, 1991: 38.

10 “Two Minor Leaguers to Vie for Davis’ Role,” The Sporting News, January 21, 1991: 39.

11 Neil Hohlfeld, “Houston Astros,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1992: 19.

12 The Sporting News, July 8, 1996: 25.

13 Finley discussed this approach —without any mention of steroids —in a segment that aired on Fox Sports’ San Diego station in August 2018, available at foxsports.com/san-diego/video/1299911235524.

14 Steven Kutz.

15 Ibid. A video of the walk-off grand slam, called by Vin Scully, is available at youtube.com/watch?v=d5NdnmQ_XSA.

16 audioboom.com/posts/6148920-tincaps-interview-steve-finley-padres-player-development-special-assistant.

17 linkedin.com/in/steve-finley-68189730/; fa.morganstanley.com/rsf/mediahandler/media/9974/Steve%20Finley,%20Athletes%20Quarterly%20article.pdf

18 Tanya Mannes, “Ex-Padre Finley Strikes Out as Restaurateur,” San Diego Union Tribune, February 21, 2010. sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-ex-padre-finley-strikes-out-as-restaurateur-2010feb21-story.html.

19 insideweddings.com/weddings/meaghan-hunt-and-steve-finley/434/.

20 Steven Kutz; worldsurfleague.com/athletes/12791/austin-finley.

Full Name

Steven Allen Finley

Born

March 12, 1965 at Union City, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.