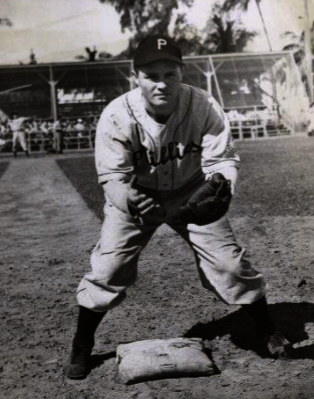

Pinky May

Those who served during World War II were collectively known as the Greatest Generation. Many young, and not so young, men went into the service during that time and returned home to resume their lives. But for those whose lives had been baseball, they often found that their days of playing major-league baseball were over.

Those who served during World War II were collectively known as the Greatest Generation. Many young, and not so young, men went into the service during that time and returned home to resume their lives. But for those whose lives had been baseball, they often found that their days of playing major-league baseball were over.

One such player was Merrill Glend “Pinky” May, who in the five seasons prior to going into the Navy after the 1943 season had played in more than 100 games at third base in each season for the Philadelphia Phillies. They were to be his only seasons at the major-league level.

May was born on January 18, 1911, in Laconia, Indiana. He was the fifth of six children born to Perry and Anna May. By the time the United States entered World War II, May was over 30 and had completed his third major-league season with the Phillies.

Perry May was a farmer in Laconia and would scold Merrill for playing ball on weekends, not realizing that his son could make a living at the game. Merrill graduated from Laconia High School in 1928, and went on to play at Indiana University. While at Indiana, he was scouted by Paul Krichell of the New York Yankees. After May completed his studies in 1932, Krichell signed him to a Yankee contract. Years later, Pinky looked back on the signing of his first contract as his biggest thrill. “As a young boy, I thought that ballplayers were on a different plateau than ordinary human beings,” he said. “It, being a professional baseball player, was something that an ordinary person couldn’t reach. But I reached it and was happy just to think I was going to get paid just to play baseball. I must have set a record for a long-distance run, because when I signed that first contract, I was in college and my coach had called me on the phone to say that Mr. Krichell was in his office and wanted to sign me to a Yankee contract. I was two miles away and ran the whole way.”1

May came to professional baseball without a nickname, but that was about to change. As he told it, “I got the nickname Pinky when I first got into professional baseball. When I arrived at my first minor-league team, sportswriters asked me what my nickname was and I told them I didn’t have one. I did tell them that when I played at Indiana University, that a couple of the boys on my team did call me Pinky, but the name never stuck. That was good enough for them because after that they always wrote my name up as Pinky, and it’s been Pinky ever since.”2 In those college days, May was so intense that his cheeks would glow bright red when his temper was not under control. Thus his teammates took to calling him “Pinky.”

May’s first stop was at Cumberland (Maryland) in the Class C Middle Atlantic League. In his first minor-league season, Pinky was playing in West Virginia and the hotel accommodations were not that good. There wasn’t even a sink in the room. The players were provided a water basin and a pitcher. When Pinky was finished, he saw a policeman down below and, very uncharacteristically, deposited the water atop the cop. He quickly concluded that his prank was not the smartest of ideas. May hastily departed the room and raced toward the lobby. He mingled with his teammates, waiting for the bus to the ballpark. The enraged patrolman was able to determine that the water came from May’s room and went looking for the young player. His fellow players covered for him and off to the ballpark they went.

May batted .264 for Cumberland and was promoted to Durham in the Class B Piedmont League for the 1933 season. Manager Bill Skiff switched him from the outfield to third base.3 During those early minor-league seasons, May was still under the wing of Paul Krichell, who convinced him that he wouldn’t succeed unless he learned to hit to all fields. At Durham, hitting to all fields, he batted .309. However, with the Depression in full swing, times were tough and Pinky and the rest of the team agreed to take a pay cut. “So I ended up playing in 1933 for $150 per month. And, you know, that was enough to get by on.”4

In 1934 May moved up to Binghamton in the Class A New York-Penn League and batted .301 with 69 RBIs.

His next four years were spent at Double-A which at the time was the highest level of minor- league baseball. Except for most of the 1937 season, which he spent at Oakland (Pacific Coast League), he played with the Newark Bears.5 At the end of the 1936 season, during which he hit .280 with 10 homers and led the league’s third basemen in fielding, he was recalled by the Yankees but did not get into any games with New York. At Oakland in 1937, he batted .304 in 120 games.

In 1938, with Newark, May batted.331. He had 53 extra-base hits (including a career-high 12 home runs), and 108 RBIs, but the Yankees, who had just won their third consecutive World Series, were set at third base with Red Rolfe. May had his best game ever on May 1 of that year when, in four trips to the plate, he drove in four runs with two homers, a single, and a double as the Bears defeated Rochester, 12-8.6

While May was at Newark in 1935, fellow Laconian Art Funk was playing for Louisville. They got to be friends. On one occasion the two players were driving and Art brought along his 18-year-old niece Veneva Jane Weaver. It was the first meeting for Pinky and Jane. The two were married on February 25, 1939. Pinky and Jane were married for 61 years and had three children (Merrill, Milt, and Mira Jane), five grandchildren, and 14 great-grandchildren. Pinky would ultimately take over the farm and sold it when his family relocated to St. Petersburg, Florida in 1960.

May was frustrated at being trapped in the Yankee farm system for so long. In those days, only one ballplayer could be drafted off any one minor-league club. The Yankees had Double-A clubs in Newark and Kansas City and a working arrangement with Oakland in the Pacific Coast League. “They put their best players on the Newark roster so when one was drafted, the others were protected,” May told a sportwriter.7

After the 1938 season, May was drafted by the last-place Philadelphia Phillies, and he finally made it to the majors with Philadelphia in 1939 at the not-so-tender age of 28. “I was fortunate that I got drafted at the end of that 1938 season,” he said. “That gave me a chance to play in the major leagues. It didn’t bother me that the Phillies were a last-place team. It was still major-league baseball, and I was going to get my chance.”8

In 1939 May had a good spring with the Phillies, but it briefly appeared that he would be sidelined, as he twisted his spinal column chasing a foul pop on March 30 in an exhibition game. He was hospitalized briefly, but whipped himself back into shape and missed only the season opener.

May’s first major-league hit came in a 5-4 12-inning win over Brooklyn on April 23, 1939. His sixth-inning single off Brooklyn’s Whitlow Wyatt drove in two runs and gave the Phillies a 3-0 lead. The Dodgers tied the game and the contest went into extra innings. In the decisive 12th inning, May walked and scored the tying run after the Dodgers had taken a 4-3 lead in the top of the inning.

In the very early going, it appeared that the Phillies might escape their doormat status. They won four games in a row from April 22 through April 25 and had a 4-2 record through six games. In the April 25 game, an 8-1 win over the Giants, May went 2-for-4 with an RBI and a stolen base. By May 6 he had six multiple-hit games to his credit, and his batting average stood at .422.

May’s first career four-hit game came on June 5, 1939, when he went 4-for-4 with two RBIs in an 8-7 win over the Cubs. His batting average stood at .333. The following day, with Philadelphia down 8-6 going into the bottom of the ninth, May’s hit was the second of five consecutive Phillies singles that allowed them to rally for a 9-8 win.

May was definitely not a home-run threat and his only two round-trippers of 1939 came in back-to-back games on August 12 and 13 against the Giants at the Polo Grounds.

The Phillies, despite May’s efforts, slipped into the cellar on May 18 and remained there for the balance of the season. There were few bright spots, as the team went 45-106 for the season, 18 games behind the seventh-place Braves and 50½ games behind the pennant-winning Reds. During each of May’s first four seasons with the Phillies, they lost at least 100 games.

For his rookie season, he batted .287 with 67 RBIs. His 41 walks gave him an on-base percentage of .346. He tied for the league lead with 25 sacrifice hits, and posted the best fielding percentage among the National League’s third basemen. In his five seasons with the Phillies, he led the league’s third basemen in fielding three times. The other two seasons, he finished second.

May was named to the All-Star team in 1940, in his second major-league season. He was part of a Phillies infield (Art Mahan, 1B; Herman “Ham” Schulte, 2B; Bobby Bragan, SS; and May) that was described as the “Pepper Pots” by sportswriters for their sure-handed fielding.9 In two plate appearances in the All-Star Game, he flied out and was hit by a pitch, as the National League won 4-0.

The third baseman batted .293 with a career high 147 hits in 1940. Both figures were the best on the Phillies that season and he tied for the team lead in doubles with 24. During the course of the season, he had 11 three-hit games. From August 14 through August 26, May put together a career-best 14-game hitting streak, and his batting average was .300 as late as September 19. A late-season slump sent him below .300. The Phillies finished at 50-103, completing their third consecutive year in the basement.

In 1941 May got off to a terrible start, batting .134 (13-for-97) in his first 26 games. But he turned things around and batted .300 for the balance of the season to wind up with a .267 average (but with no home runs and only 21 extra-base hits). His fielding numbers were the best of his career. He led the National League with career highs in fielding percentage (.972), putouts (194), assists (324), and double plays (31). But the Phillies once again were in the cellar, this time with a 43-111 record, their lowest winning percentage during May’s time in the City of Brotherly Love. Teammate Danny Litwhiler remembered, “We all pretty much stuck together. It was a good group of guys. No one got angry with anyone else. We didn’t blame each other for what happened. We got on pretty well, considering.”10

During the 1942 season, May roomed with Ernie Koy, another player whose career was interrupted by the war. Koy, like May, had originally signed with the Yankees, and the two were teammates for four seasons in the Yankee farm system. Koy entered the Navy in 1943. Koy’s assessment was that “Pinky May was a great third baseman, but he couldn’t run. We would take Pinky down the right-field line before a game and try to teach Pinky to run faster, but he just couldn’t. Pinky should have made the majors long before he did.”11

May had an off-year in 1942, playing in only 115 games and batting .238. The team sank to a new low, winning only 42 games, the least of any Phillies team in the 20th century. Mercifully, three games were postponed and not made up. The manager that year was Hans Lobert, and he was so concerned about the opposition stealing signs that he used a different set of signs for each player on the team. He used word signals, and the bunt sign for May was “Chatfield.”12 If anyone was confused by this, it was most definitely not the opposition.

In 1943 May returned to form, batting .282 in 137 games. The game against the Pirates on October 3 was his last in the majors. His batting average was the second best on the team, and his on-base percentage of .369 led the Phillies. The team improved, too, winning 64 games and climbing out of the cellar after five consecutive eighth-place finishes. Even the players’ wives were part of the team’s success. Pinky’s wife, Jane, along with the wives of Danny Litwhiler, Ron Northey, and Si Johnson, gave up eating steaks, handing over their war ration points to their husbands, so as to make them stronger.13 Pinky’s RBI count increased from 18 to 48, and the team’s home run production, with Northey leading the way with 16, jumped from 44 (worst in the league) to 66 (third).

As late as June 30 the Phillies were in fourth place, and within a game of .500. Could this continue? On July 8, the second game of a doubleheader against Cincinnati was a scoreless tie in the bottom of the 14th inning. Dick Barrett, who had not won a game all season, had pitched 14 shutout innings for Philadelphia. With the winning run at third base and two out, manager Bucky Harris summoned May to pinch-hit for his pitcher. May’s single scored Coaker Triplett with the winning run. By that point, the Phillies had slipped to fifth place, but were still within 11 games of the league lead. They would not get any closer, although they put together a seven-game winning streak in August. They eventually sank to seventh place, 41 games behind the pennant-winning St. Louis Cardinals.

Bucky Harris had become the Phillies manager at the start of the season. On July 28 he was abruptly fired by team owner William D. Cox. Freddie Fitzsimmons managed the team for the balance of the season. Harris had an impact not only on May the player, but also on May the man. May said Harris had the happy faculty of making the players believe they could win a game that appeared to be hopelessly lost.14 Harris’s record with the Phillies was 39-53.

In that October 3 game, May had four hits as the Phillies swept a twin bill from the Pirates to finish at 64-90. His 4-for-10 day brought his batting average to .282. May, who once again led the league’s third basemen in fielding percentage, would never again play an inning of major-league baseball. He enlisted in the Navy after the season, and played for Lieutenant Mickey Cochrane‘s Great Lakes Naval Station team in 1944, then was sent to Hawaii at the beginning of 1945 as part of the Western Pacific Tour squad that played before fighting troops on Pacific Islands. He was then assigned to the island of Tinian, where the Quonset hut he lived in was less than 100 yards from an airstrip. He spent many evenings watching B-29s take off to bomb Japan.15 On August 6, 1945, he was watching as the Enola Gay took off at 2:45 A.M. and headed toward Hiroshima.

May returned to the Phillies after the war, only to be released on May 7, 1946. He had an opportunity to resume his playing career with the Pirates in 1947; in need of third-base help, they offered him a job. But Pinky elected to forgo playing in the majors, and embarked on a managerial career. In 1947 he joined the Albany Senators, the Pirates’ affiliate in the Eastern League, as a player-manager. In his first season, he batted .322 as the team finished in second place with an 80-58 record. In the playoffs the Senators defeated Scranton in seven games before losing to Utica in the final series.

Charles Young, in Albany’s Knickerbocker News summed up May’s qualities, both as a man and as a manager: “May is serious virtually all the time. No man has more of the will to win spirit in baseball. He talks, eats, and sleeps baseball. Playing for May is a breeze if the players cooperate with him.” May didn’t expect the player to “do the impossible.” On the other hand, he did not have “any use for a player who does not give 100 per cent effort at all times.”16

May eased himself out of the lineup over the following two seasons (1948-49), playing his final minor-league game (with the exception of a lone pinch-hitting appearance later in his career) in 1949. In 1949 his Albany Senators, led by pitcher Orie “Old Folks” Arntzen’s 25-2 record, won the pennant,17 but lost in the playoffs. In 1950 they slipped to fourth place. Pittsburgh severed its working arrangement with Albany before the 1951 season and May’s team finished in eighth place.

May left Albany and moved on to the Cleveland Indians’ organization in 1952. His first stop was Spartanburg, South Carolina, in the Class B Tri-State League. He managed the team, which included a young Rocky Colavito, to third place. The following season, May led the Sherbrooke Indians, who finished first in the Provincial League with an 84-41 record but lost in the first round of the playoffs.

After spending 1954 managing Reading in the Eastern League, May moved on to Keokuk, Iowa, where his 1955 team, the Kernels, finished first with a 92-34 record in the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League, the best winning percentage of May’s managerial career, and won the league playoffs. The fans were so elated that they presented him with a thoroughbred heifer for his farm in Indiana.18 When baseball historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright compiled their list of the best 100 teams in minor-league history, the 1955 Kernels ranked 30th.19 May’s star player was 19-year-old Jim “Mudcat” Grant, who posted a 19-3 record in his second professional season.

In 1958 May’s Class B Alamance (Burlington, North Carolina) team qualified for the Carolina League playoffs, after being in the cellar on July 8 and in seventh place, just two games ahead of the last-place team at the end of July. The common refrain was “all the way with Pinky May.”20 The team finished fourth with a 70-67 record and won the league championship by defeating Danville and Greensboro in the playoffs. May’s top players were pitcher Steve Hamilton and outfielder Walt Bond.21 At one point during the season, May grabbed his bat for a pinch-hitting appearance, but failed to reach base safely.

May continued to manage in the Indians’ organization through 1962. In his third season at Burlington in 1960, he was chosen the Carolina League’s Manager of the Year as he brought his team from far behind to win second-half honors with a 41-29 record, and a place in the playoffs against first-half winner Greensboro. Burlington had gone 26-44 to finish dead last during the first half, and were 2-8 after ten games in the second half before storming back to win 39 of their last 60 games. But May’s Burlington squad lost the best-of-seven playoff final in five games.

May spent 1961 season with Dubuque in the Class D Midwest League, where his son Milt was the team’s batboy. Pinky moved on to the Selma Cloverleafs in the Class D Alabama-Florida League in 1962. His star player, as the team swept through the playoffs to the league championship, was 18-year-old Lou Piniella, who was in his first year of professional ball. Piniella remembered May taking him under his wing when he reported to Selma and got off to a bad start. May’s advice to Piniella was, “You have to prove you can hit the fastball. Nobody plays in the big leagues without being able to hit the fastball first. Show us you have power and strength. We’ll teach you how to hit a curve ball. I guarantee it. First I want you to hit the fastball, regain your confidence, and get comfortable with your swing.” Piniella was on his way, and in 1969, he was American League’s Rookie of the Year. The 1962 season was the last for Selma and for the Alabama-Florida League, as Alabama Governor George Wallace stood in the way of integration when every other league in Organized Baseball accepted black players.22

May left the Indians organization and spent the early part of the 1963 season with the Fort Lauderdale Yankees, before being fired on June 26. He was with the Reds organization from 1964 through 1966. His 1965 Tampa and 1966 Peninsula clubs included future stars Bernie Carbo, Johnny Bench, and Hal McRae. In June 1965 he and Jack Cassini switched teams, with May heading from the Tampa Tarpons in the Florida State League to the Peninsula Grays (Hampton, Virginia) in the Carolina League. May took over a team with a 23-31 record. Peninsula went 63-27 the rest of the way to win its division by ten games.

On June 21, 1966, May became the last man to manage Satchel Paige. The Grays brought in Paige as a publicity stunt and the ancient one, then age 59, pitched his last two professional innings.23

May returned to the Indians in 1967 and managed at the Class A and Rookie levels through 1972. In 1969, when he managed the Statesville-Monroe team in the Western Carolinas League, the lineup of the opposing Gastonia team featured an 18-year-old catcher in his second year in the minors. The kid got into 86 games and slugged 11 homers, including ten against May’s team. The kid happened to be Pinky’s son Milt. In a game on June 11, Pinky was ejected from the game for protesting that Milt’s inside-the-park homer should have been ruled a ground-rule double as his line drive had become lodged in the batting cage that was being stored down the left-field line. Milt also gunned down three of Pinky’s runners who were trying to steal third base.24

On July 9 at Gastonia, Milt hit two homers. The next night Milt hit another pair of four-baggers, this time in successive at-bats,25 and the next time up, Pinky ordered his pitcher to throw at Milt.26 During the at-bat in the seventh inning, three pitches came at Milt before he was walked. On ball four, he was sprawled in the dirt and looked toward the opposition dugout where his father was smiling. Pinky’s wife, Jane, bawled him out for having his pitcher throw at Milt. Unfazed, Milt slammed another pair of homers against Pinky’s team on July 25.27

In 1970 Pinky managed Reno to a second-place finish in the Class A California League with a 79-61 record. He remained with Reno through 1971 and was with the Indians affiliate in the Gulf Coast League in 1972. He was slated to return that position in 1973, but resigned on February 15.

In his 26-year managerial career, May put together a record of 1698-1580. After retiring from managing, he worked in a chain of liquor stores in the St. Petersburg, Florida, area for about ten years.

In 1986, Pinky and Jane moved to San Antonio, Texas, to be closer to their older children, Merrill and Mira.

The May family was on the verge of having three generations succeed in professional baseball when fate intervened in 1990. Milt’s son Scott, a student at Manatee (Florida) High School, was involved in an automobile accident on December 24, 1990, suffering life-threatening head injuries. He recovered and resumed his baseball efforts at Manatee Community College and Carson-Newman (Tennessee) College. In 1996 he was drafted by the Pirates in the 41st round.28 He batted .250 in 44 games during 1996 and 1997 at Erie in the New York Penn League and Augusta in the Sally League, after which he left baseball and became involved in the family’s orange groves in the Bradenton area, as well as coaching high-school and Little League ball.

In his later years, Pinky May returned to Indiana, where he died on September 4, 2000. He was survived by his wife, Jane, and their three children, Merrill, Milt, and Mira Jane. Jane, who spent her last years living with her daughter in San Angelo, Texas, died on September 30, 2010, at the age of 92.

May was inducted into the Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame in 2003. In 2009 his hometown of Laconia, Indiana, honored him, and his son Milt by naming the town’s baseball complex in their honor. The renamed May Fields opened on July 4, 2009.

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Piniella, Lou, and Maury Allen, Sweet Lou (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1986).

Roberts, Robin, and C. Paul Rogers, III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996).

Van Blair, Rick, Dugout to Foxhole: Interviews with Baseball Players Whose Careers were Affected by World War II (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 1994).

Cameron, Brad, “Bees Commemorating ’55 Keokuk Kernels with Special Jerseys for Tonight’s Game, Daily Gate City (Keokuk, Iowa), June 21, 2002.

Gaven, Michael F., “Minors Worth Watching,” Newark (New Jersey) Star Eagle, July 7, 1938.

Hunter, Bill, “Pinky Recalls Hamilton, Bond and Playoff Champs of 1958,” Burlington (North Carolina) Daily Times-News, June 10, 1965, 2B.

Young, Charles, “Sports Stadium: Rip Collins and Pinky May Are Compared; Both Managers are Easy on Their Players; Present Albany Boss More Serious Than Jimmy,” Knickerbocker News (Albany, New York), April 3, 1948, 10-B.

Albany Times-Union

Burlington (North Carolina) Daily Times-News

Gastonia (North Carolina) Gazette

Hartford Courant

New York Times

The Sporting News

Ancestry.com

FultonHistory.com

GenealogyBank.com

NewspaperArchive.com

Newspapers.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Pinky May file at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Interviews with Milt May, February 11 and March 4, 2014.

Interview with Merrill May, March 14, 2014.

Notes

1 Van Blair, 131, 137.

2 Van Blair, 128.

3 Gaven, July 7, 1938

4 Van Blair, 129

5 At the time, Double B was the highest level of minor-league ball, equivalent to today’s Triple A.

6 New York Times, May 2, 1938, 21.

7 Van Blair, 129

8 Van Blair, 129

9 Tom Mahon. Philadelphia Daily News, July 1, 1993.

10 Ed Hilt, The Press (Atlantic City, NewJersey), July 10, 1997.

11 Van Blair, 85

12 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers, III, 23.

13 Racine (Wisconsin) Journal Times, April 30, 1943, 16

14 Young, April 3, 1948

15 Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball in Wartime,” 2008

16 Young, April 3, 1948.

17 Hartford Courant, August 28, 1949, 10.

18 Ronald Melcher, “Grist from the Sports Mill,” Hartford Courant, September 10, 1955, 13.

19 Brad Cameron, June 21, 2002.

20 Burlington (North Carolina) Daily Times-News, June 8, 1965, 2B

21 Bill Hunter, “Pinky Recalls Hamilton, Bond and Playoff Champs of 1958,” Burlington (North Carolina) Daily Times-News, June 10, 1965, 2B.

22 Lou Pinella and Maury Allen, 33-34.

23 Mike Holtzclaw, Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia), August 21, 1994.

24 Dwight Frady, “G-Pirates Roll, 14-1: Bucs Win, So do (Greenwood) Braves,” Gastonia (North Carolina) Gazette, June 12, 1969, 2-B.

25 Neal Patrick, “Milt Hits Two More Homers Against Pop Pinky’s Team,” Gastonia (North Carolina) Gazette, July 11, 1969, 2-B.

26 Larry Hug, Evening Independent (St. Petersburg, Florida), August 23, 1969, C1.

27 Gastonia (North Carolina) Gazette, July 26, 1969, 2-B

28 Bradenton Herald, June 9, 1996.

Full Name

Merrill Glend May

Born

January 18, 1911 at Laconia, IN (USA)

Died

September 4, 2000 at Corydon, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.