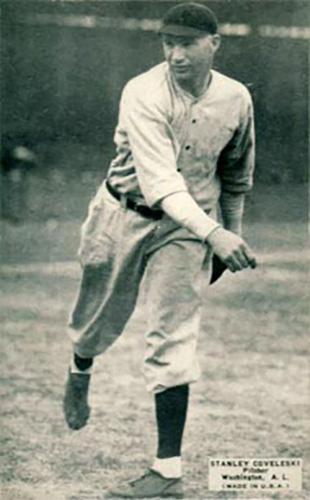

Stan Coveleski

With one of the finest spitballs in baseball history, Stan Coveleski baffled American League hitters from the final years of the Deadball Era into the 1920s. To keep hitters off balance, Coveleski went to his mouth before every pitch. “I wouldn’t throw all spitballs,” he later explained. “I’d go maybe two or three innings without throwing a spitter, but I always had them looking for it.” Though he led the American League in strikeouts in 1920, Coveleski prided himself on his efficient pitching. “I was never a strikeout pitcher,” he recalled, “Why should I throw eight or nine balls to get a man out when I got away with three or four?” The right-hander often boasted of his control, once claiming he pitched seven innings without throwing a ball; every pitch was either hit, missed, or called a strike. During his 14-year career, Coveleski ranked among the league’s top ten in fewest walks allowed per nine innings pitched seven times.

With one of the finest spitballs in baseball history, Stan Coveleski baffled American League hitters from the final years of the Deadball Era into the 1920s. To keep hitters off balance, Coveleski went to his mouth before every pitch. “I wouldn’t throw all spitballs,” he later explained. “I’d go maybe two or three innings without throwing a spitter, but I always had them looking for it.” Though he led the American League in strikeouts in 1920, Coveleski prided himself on his efficient pitching. “I was never a strikeout pitcher,” he recalled, “Why should I throw eight or nine balls to get a man out when I got away with three or four?” The right-hander often boasted of his control, once claiming he pitched seven innings without throwing a ball; every pitch was either hit, missed, or called a strike. During his 14-year career, Coveleski ranked among the league’s top ten in fewest walks allowed per nine innings pitched seven times.

Stan Coveleski was born Stanislaus Anthony Kowalewski to a family of Polish descent on July 13, 1889 in Shamokin, Pennsylvania, a coal mining town located 60 miles north of the state capital in Harrisburg. “Covey” later recalled working in the local mines by the time he was 12 years old, from seven in the morning to seven at night six days a week for $3.75 per week. The youngest of five boys – four of whom would play professional baseball – Stanley, like his older brother Harry, who won 81 games for the Phillies, Reds, and Tigers, anglicized his name to Coveleski when he moved into organized baseball (at some point after retirement the final ‘e’ came off his name). His oldest brother Jacob died during the Spanish-American war. Frank spent time with an outlaw club in Pennsylvania but fell victim to rheumatism that ended his career. John, a third baseman and outfielder, played in the minor leagues but could never quite break through.

As a young boy Coveleski built up his strength by hauling timber for the miners, stopping every now and then to throw rocks at birds. When he got home, Stan continued to practice by throwing rocks at tin cans; he later claimed he could even hit them blindfolded. It was while throwing at cans, Covey later recalled, that he was approached by a local school teacher to pitch on the school team.

In 1909 Coveleski signed with Lancaster of the Tri-State League. Stanley and his brother John were watching a movie when someone went to the front of the theatre and announced, “If Mr. Coveleski is in the house, he is wanted at the box office.” Neither knew which brother was wanted so both went and found the Lancaster manager waiting for them. It turned out he was looking for Stanley, but the unworldly and shy youngster was reluctant to sign. Only when the manager agreed to sign older brother John as well would Stan agree to join the club. By that time Coveleski had graduated to hauling and sawing wood for the miners, and his weekly pay had grown to $9.00, far below the $250 per month Lancaster offered him.

Coveleski hurled admirably in his first season in the league; in 272 innings pitched he led the league with 23 wins while losing only 11. His next two years, also in Lancaster, proved satisfactory – if not as spectacular as his rookie season. In 1912 he moved to Atlantic City in the same league and continued pitching well, finishing the season with 20 wins and a 2.53 ERA. Near the end of the 1912 season Coveleski caught the eye of manager Connie Mack from the nearby major league Philadelphia Athletics. Signed to a contract and given a couple of late-season starts, the 23-year-old Coveleski acquitted himself well, but Mack believed he needed additional seasoning. Accordingly, the manager sent Covey across the country to Spokane in the Northwestern League, apparently believing that he had a gentleman’s agreement with Spokane to retain the rights to the promising young pitcher.

Coveleski played two years in Spokane, hurling over 300 innings each year. In his stellar sophomore campaign Coveleski won 20 games and led the league in strikeouts. After the 1914 season, Portland of the Pacific Coast League traded five players to Spokane to acquire Coveleski, now considered the Northwestern League’s top pitcher. According to one story Mack had forgotten about his rights to Coveleski and failed to take up his claim for the player. Later, upon inquiring about Covey, Mack was sent a box of big red apples as thanks and told his rights had expired.

Despite not being particularly large at 5’11” and 166 pounds, Coveleski was bestowed the nickname The Big Pole. He typically threw overhand, but would drop down to a sidearm delivery once in a while. While at Portland Coveleski developed the spitball for which he later became famous. Coveleski felt that to become a top flight hurler he needed a pitch to supplement his fastball, curve, and slow ball. Covey developed excellent control of his spitball which he could make break in three directions depending on his wrist action: down, out, or down and out.

When he first started experimenting with the spitball he tried using tobacco juice. Later, at the suggestion of Joe McGinnity and Harry Krause, he switched to alum which worked much better. Covey kept the alum in his mouth where it became gummy; he would wet his first two fingers to throw the spitter. With his newly developed spitball, Coveleski led the Pacific Coast League in games pitched and finished the 1915 season 17-17 with a respectable 2.67 ERA. Despite his .500 record, Covey remained favorably regarded and prior to the 1916 season the Cleveland Indians, who enjoyed a close relationship with Portland, purchased his contract.

Coveleski was scheduled to pitch during the 1916 season’s first week against the Detroit Tigers and his brother Harry, a star coming off two straight 20 win seasons. Harry, however, demurred from pitching against his younger brother and the much-heralded matchup never occurred. Coveleski lost his first start, but went on to a respectable rookie season, finishing 15-13 with an ERA of 3.41. Cleveland won 77 games in 1916, 20 more than the club’s 1915 total.

In 1917 Cleveland and Coveleski both continued to improve. The team jumped to 88 wins and a third-place finish; Coveleski won 19 of those games, finished third in the league with a 1.81 ERA, and led the circuit with nine shutouts. During the war-shortened 1918 season, Coveleski was even more brilliant, ranking second in the league in ERA (1.82) and wins (22). One of those victories was a complete-game, nineteen-inning 3-2 victory over the New York Yankees on May 24. Thanks to Coveleski’s strong pitching, the Indians finished in second place, 2.5 games behind the Boston Red Sox. Cleveland finished second again in 1919, and Coveleski once again turned in a stellar performance, posting a 24-12 record with a 2.61 ERA.

Though he could be taciturn and ornery on days when he pitched, off the field Coveleski was generally considered friendly, though not particularly talkative. Stan also indulged a lively but sometimes malicious sense of humor. At spring training in 1921 in Dallas, manager Tris Speaker invited the team down to his nearby home for a barbeque. Coveleski and shortstop Joe Sewell took a rowboat out on the lake. Once out a ways from shore, Covey asked Sewell if he could swim. The rookie replied in the negative whereupon Coveleski shoved him into the lake and rowed away. A rescue party saved Sewell; Coveleski never explained himself, thinking the prank very funny.

1920 would prove to be a year of tragedy and triumph for both Coveleski and the Cleveland Indians. Covey, one of the 17 pitchers allowed to continue throwing the banned spitball under the grandfather clause, started the season hot by winning his first seven starts. On May 28, however, he received the tragic news that his wife of seven years, Mary Stivetts, had died. Although she had been sick for some time, her death was unexpected. Coveleski returned to Shamokin, where the broken-hearted pitcher grieved with his family before finally returning to the team on June 4. A couple of years after his wife’s death, Coveleski married her sister, Frances, who had been helping care for his two children, William and Jack. Covey’s second marriage would last until his death many years later.

On August 17, 1920 tragedy again struck the Cleveland Indians, with the death of shortstop Ray Chapman following a beaning at the hands of New York pitcher Carl Mays. Coveleski, who had been the opposing pitcher in the game, later recalled that he did not think Mays was purposely trying to hit Chapman but “at that time if we saw a fellow get close to the plate, we’d fire under his chin.”

Despite these tragic circumstances, both Coveleski and the Indians persevered to narrowly win the American League pennant. Once again, Coveleski was a big reason for the Tribe’s success, winning 24 games, finishing second in the league with a 2.49 ERA and leading the league with 133 strikeouts. His best work he saved for that year’s best-of-nine World Series against the Brooklyn Robins, pitching three complete-game victories, including a shutout in the series-clinching Game Seven. Covey posted a 0.67 ERA for the series, while walking only two batters in 27 innings.

From 1921 through 1924 Cleveland gradually fell out of contention as ownership did little to improve the ball club. In 1921 Covey won 23 games: his fourth straight year of at least 22 victories. Although his win totals declined thereafter as the fortunes of the team waned, Coveleski continued to pitch well, winning his first ERA title in 1923.

After a sixth-place finish in 1924, the Indians traded Coveleski, coming off a subpar year (15-16, 4.04 ERA) to the world champion Washington Senators. Despite having spent nine years of his career there, Coveleski had no regrets about leaving Cleveland behind. “I never did like Cleveland,” he later explained. “Don’t know why. Didn’t like the town. Now the people are all right, but I just didn’t like the town.” He even admitted that his dissatisfaction with his surroundings had come to affect his performance. “You know I got to a point where I wouldn’t hustle no more,” Covey remembered. “See, a player get to be with a club too long. Gets lazy, you know.”

True to form, Coveleski rebounded strongly for the Senators in 1925, finishing the season with a 20-5 record and capturing his second ERA title with a 2.84 ERA, though he lost both of his starts in Washington’s World Series defeat against Pittsburgh. After turning in another good year in 1926, Coveleski came down with a sore arm in 1927 and the Senators gave him his unconditional release. Covey caught on with the Yankees for the 1928 season, but pitched poorly and was released in August.

Now out of baseball and with the opportunity to coach a boys’ amateur team, Coveleski moved his family to South Bend, Indiana, where he and his wife purchased a home on Napier Street from the Napieralskis, one of the city’s founding pioneer families. Coveleski then acquired and ran the Coveleski Service Station on the city’s West Side. During the Great Depression, however, both gas and business became hard to come by, and Covey quit the business. Coveleski, now fully retired, spent his time hunting and fishing – often driving to a nearby lake at 6 A.M. – and generally enjoying life, although he had to endure the death of his son Jack in 1937.

On the strength of his 215 career wins and lifetime .602 winning percentage, Coveleski was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1969. In his own stoic way he expressed both his appreciation and frustration for having to wait so long: “It makes me feel just swell,” he said. “I figured I’d make it sooner or later, and I just kept hoping each year would be the one.” Coveleski died at the age of 94 on March 20, 1984 in a nursing home after a lengthy illness; he was buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery in South Bend. At the time of his death he was the oldest living Hall of Famer.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Armour, Mark L. and Daniel R. Levitt. Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got That Way. Brassey’s, Inc., 2003.

Baseball Magazine, July 1916.

Baseball Quarterly, Fall, 1977.

Cohen, Richard M., and others. The World Series. The Dial Press, 1979.

Stanley Coveleski file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Coveleski, Stanley. Uncredited Interview, Stanley Coveleski file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Danzig, Alison and Joe Reichler. The History of Baseball: Its Great Players, Teams and Managers. Prentice Hall, 1959.

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. The Free Press, 2001.

James, Bill and Rob Neyer. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. Fireside, 2004.

Karst, Gene and Martin J. Jones Jr. Who’s Who in Professional Baseball. Arlington House, 1973.

Lewis, Franklin. The Cleveland Indians. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1949.

Lieb, Frederick C. Connie Mack. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945.

Murdock, Eugene. Baseball players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game, 1920-1940. Meckler, 1991.

Neft, David S., Richard M. Cohen, and Michael L. Neft. The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball 2001. St. Martins Griffin, 2001.

Palmer, Pete and Gary Gillette eds. The Baseball Encyclopedia. Barnes & Noble Books, 2004.

Pietrusza, David, Matthew Silverman and Michael Gershman, eds. Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. Sport Media Publishing, Inc., 2003.

Reach’s Official Baseball Guide. A. J. Reach Co., various years.

Ritter, Lawrence S. The Glory of Their Times. Vintage Books, 1985.

Smith, David, et. al. Retrosheet website. www.retrosheet.org.

Sowell, Mike. The Pitch That Killed. Macmillan Publishing Company, 1989.

Chicago Tribune

Los Angeles Times

New York Times

The Sporting News

Full Name

Stanley Anthony Coveleski

Born

July 13, 1889 at Shamokin, PA (USA)

Died

March 20, 1984 at South Bend, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.