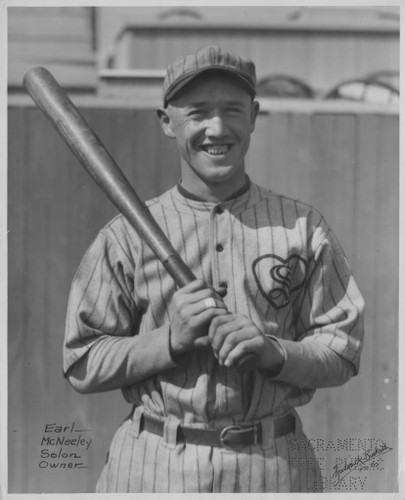

Earl McNeely

A 26-year-old rookie who came up in August, George Earl McNeely drove in the winning run in the 12th inning of the seventh game in the 1924 World Series, Washington’s only championship. Before his playing days ended, McNeely, known by his middle name, managed—and owned—a Pacific Coast League team.

A 26-year-old rookie who came up in August, George Earl McNeely drove in the winning run in the 12th inning of the seventh game in the 1924 World Series, Washington’s only championship. Before his playing days ended, McNeely, known by his middle name, managed—and owned—a Pacific Coast League team.

McNeely was born on May 12, 1898, in Sacramento, California, to William C. and Clara (Bateman) McNeely. His father, born in Pittsburgh, worked on horse saddles and made harnesses. His mother was born in Nevada. Earl’s paternal grandfather was born in Scotland and his paternal grandmother was from Ireland. William McNeely, 19 years older than his wife, was already 50 when Earl was born. Clare McNeely worked at home, raising their six children.1

Earl was the second-youngest of the six. He had an older brother and three older sisters. A younger brother was born in 1903. Growing up in the Sacramento area, where he spent his entire life, Earl attended the Oak Park School through eighth grade before playing basketball and soccer at Sacramento High School. The same school later produced Stan Hack, longtime Cubs third baseman. McNeely didn’t play baseball there, however.

“I was considered too small by the coach” for the varsity baseball team, McNeely told a reporter in September 1924. “I had to confine my playing with ‘kid’ teams in my section of town (but) I was always thinking, talking or playing baseball.”2

By the time he graduated, a war was raging in Europe. McNeely landed a job as a rod man, an entry-level position, on a surveying crew with the state Highway Commission in Sacramento. His experience helped him get assigned to the Army’s 23rd Engineers Regiment when he enlisted in 1917. After basic training, the 23rd Engineers shipped out to France in March 1918. There McNeely and his unit took part in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, which resulted in the November 11, 1918, armistice ending the war.3

When the 23rd Engineers returned to the United States in May 1919, McNeely headed home and resumed his work on the surveying crew. He soon was promoted to leveler before being certified as a transit man. By then, his younger brother John had joined him as a rod man with the Highway Commission survey crew.

At this point, Earl fully intended to make his career as a surveyor. “In the summer months, we would be out on survey work, which prevented me from playing baseball,” he said a 1924 interview. But his work schedule gave him time to play in the semi-pro Sacramento Valley Winter League, and in late 1920, McNeely won a spot on the Lobner’s Clothing House squad as a third baseman. He played for Lobner’s again in the winter of 1921-22, performing well enough to attract the attention of scouts. “I had a great season, so much so that Charlie Pick, … manager of the Sacramento team in the (Pacific) Coast League induced me to sign a contract,” said McNeely, who at first hesitated. But knowing that he would retain his surveying certification, he had a fallback plan if professional baseball didn’t pan out.4

It took McNeely a while to adjust to the PCL. Early in the 1922 season, still playing third base, he suffered a split finger from a sharp grounder and missed some time. He was moved to the outfield to take advantage of his speed, but learning a new position took a toll on his batting. He finished the season hitting .213 in 106 games. The 1923 season was a different story. McNeely found his batting stroke and hit .333. Appendicitis, however, limited him to 75 games.

McNeely showed early in 1924 that the previous season’s batting average was no fluke. Although he never hit for power – a right-handed batter, he stood 5-foot-9 and barely weighed 150 pounds – he entered August hitting .333. He had developed into an above-average center fielder as well.

In Washington, meanwhile, owner Clark Griffith was dissatisfied with his center fielders as his team battled the Yankees and Tigers for first place. Griffith had Goose Goslin in left and preferred Sam Rice, an outstanding fielder, in right. Nemo Leibold could hit but couldn’t handle center field very well. Wid Matthews, acquired six weeks into the season, had become a fan favorite for his hustle, but had begun to slump both at bat and in the field.

Griffith sent his trusted scout Joe Engel to take a look at McNeely. Engel returned with a glowing report. Griffith agreed to purchase McNeely for $35,000 and three players, with Sacramento getting Matthews for the rest of the season. McNeely was told to report to the team when it got to Chicago. “Griffith, traveling with the team, waited for McNeely to check into the Senators’ Chicago hotel, and greeted him with ‘So you’re the fellow I paid all that money for,’ extending his hand in greeting,” Shirley Povich wrote in his 1954 team history. “‘Sorry,’ said McNeely, shrinking from Griffith’s handshake. ‘I can’t raise my right arm above my hip. Dislocated my shoulder last week in a game at Frisco.’”5

A livid Griffith wanted to cancel to deal, even calling on the commissioner to intercede. The Nats’ owner was told he could withhold payment until McNeely recovered. Indeed, Matthews had a pinch hit in Chicago on August 9, the day McNeeley made his debut as a mid-game sub in center for Leibold. McNeeley went 1-for-2. The pinch hit, Matthews’ last appearance in 1924 for the Nats, lifted his average to .305. No wonder the fans were skeptical of Griffith’s move.

Despite his shoulder injury, McNeely immediately began paying dividends. Ten days and eight starts in center fielder after he joined the team, McNeely was hitting .382. He kept his average above .300 through August, and after three hitless games dropped him to .291, he had begun a hot streak that lasted until the regular season ended. McNeely had five 3-hit games and a 4-hit game during the Nats’ September drive to the pennant. Hitting mostly leadoff, he finished at .330 in 193 plate appearances over 43 games. Griffith, well before the season ended, dropped the dispute over the McNeely deal and eventually paid Sacramento a total of $50,000.

McNeely’s play won over the critics. “The fans are certainly good to me, and it helps a lot trying to make good,” he told a reporter in early September. “The players on the team have been fine to me, too. They’re always ready to help me along.” Asked about the difference between the PCL and the American League, McNeely offered that “the Coast pitchers have more stuff” but don’t have “the control the fellows here have. Another thing that makes it easier for a batter here is that he doesn’t have to hit at bad balls because the umpires are better.”6

McNeely’s hot bat bolstered a lineup that featured Goslin (.344 with a league-leading 129 RBIs) and Rice (.334), both future Hall-of-Famers, and first baseman Joe Judge (.324). Washington won 16 of its last 21 games, a clip that was crucial with the Yankees nipping at their heels. The teams were tied as late as September 18 and New York was just a game back on September 26. The Nats clinched their first pennant by beating Boston on September 29, increasing their lead to 2 1/2 games with two to play as the Yankees were rained out in Philadelphia. McNeely was on the bench for the clincher. Harris started the left-hand batting Leibold against a right-hander. With the team’s stars resting, McNeely had two hits in a meaningless loss the next day. In the National League, the New York Giants, with a roster that featured seven future Hall-of-Famers, edged Brooklyn for the pennant.

Sentiment among baseball fans tended to be with Washington, making its first World Series, and especially with the aging Walter Johnson, finally getting into the postseason late in his brilliant career. Yet he lost Game One, despite 12 strikeouts in 12 innings. McNeely caught a fly to center for the game’s first out. He doubled and scored the Nats first run in the sixth, but the normally solid fielder “misjudged two flies” and “tried for a shoestring catch after a late start and failed” on pitcher Art Nehf’s single in the 12th. He then threw wildly to third, allowing both runners to advance.7 The Giants ended up scoring twice, the second run being the difference in a 4-3 final. Johnson lost again in Game Five as the Giants reached him for 13 hits and six runs. Despite Johnson’s two loses, the teams split the first six games, with three of them decided by one run.

McNeely played center field and led off for the Nats in six of the seven games. He pinch-hit in Game 3. He was 3-for-5 in Game Four, scoring Washington’s first run in the third and scoring again in the fifth. His second double of the Series came in the seventh inning. Washington won, 6-2, to tie the Series at two games each.

After Johnson lost Game Five, Washington held on to win Game Six, 2-1. McNeely played a key role. With two outs and Roger Peckinpaugh on third, Nehf walked McNeely. Although he was fast, McNeely wasn’t a great base-stealer. (He was successful less than 64 percent of the time in 110 attempts in his major league career.) But this time, he stole second without a throw, the Giants being wary of the tying run at third. A single to right by the 27-year-old player-manager Bucky Harris scored both runners. Tom Zachary made the one-run lead stand up to win his second game.

Game Seven was one of the classic World Series finales. As they had been for Game One, President Calvin Coolidge and his wife were in the stands at Griffith Stadium. Harris pulled a surprise, starting sore-armed Curly Ogden, but had lefty George Mogridge warming up under the stands. The plan was to ensure that manager John McGraw start the left-hand batting Bill Terry, 6-for-12 in the Series at that point, at first base. After a strikeout and a walk, Ogden was lifted for Mogridge. McGraw pinch hit for Terry in the sixth. After the Giants had taken a 3-1 lead, Harris tied it in the home eighth when his grounder to third took a bad hop and bounced over the head of Freddie Lindstrom. The common belief was that the ball hit a pebble. In any case, the hit scored two runs, giving Harris all three Washington RBIs.

The Washington rally set up a fairy-tale story. To the roar of the capacity crowd, Walter Johnson headed to the mound in the ninth inning. He worked in and out of trouble through the 12th, setting the stage for another historic bad hop, the one that would give McNeely his place in World Series history.

With one out against the Giants’ Jack Bentley, Washington catcher Muddy Ruel lifted what seemed to be an easy popup behind home plate. Circling under the ball, catcher Hank Gowdy tossed his mask away—but not far enough. As he was about the make the catch he stepped on his mask and dropped the ball. Ruel made the most of his new life and doubled to left. Johnson, a good hitter, batted for himself and grounded to short. With Ruel holding second, Travis Jackson fumbled the ball long enough for Johnson to reach. That brought up McNeely.

On the second pitch, he hit a sharp but playable grounder toward Lindstrom. Again the ball took a bad hop over the third baseman’s head. Harris, on deck, waved the lumbering Ruel home. Surprisingly, left fielder Irish Meusel made no attempt to throw out Ruel at the plate. The run Ruel scored gave McNeely the game-winning RBI, Johnson the victory and Washington its first World Series championship.

“Earl McNeely hit a chopper over Lindstrom that was a twin brother to Harris’ hit in the eighth, except that it was a little harder and therefore, a more legitimate hit,” the New York Times wrote on October 11.8 “As soon as it left the bat, it looked like a routine play at any base,” Harris wrote for the Associated Press in 1954. “I was on deck and moved behind the plate to wave Ruel home…. He was trying to force himself to run and getting nowhere. I thought he would never score.” Inexplicably to Harris, Meusel just picked the ball up and put it in his glove.9

“In the late stages of a close game,” Harris wrote, “McGraw normally shifted Ross Youngs, the right fielder and Meusel. This time he didn’t do it.”10

As Ruel slid across the plate, the Washington crowd erupted. “Before the gallant McNeely could get to the dugout, two policemen grabbed him, trying to protect the new hero. The player’s buttons were pulled from his shirt and the upper part of his uniform was torn to shreds,” the Washington Post wrote in one of the many stories that filled the next day’s front page. “Men grabbed and kissed him, while women screamed for the same opportunity.”11

In the safety of the clubhouse, the Nats were ecstatic. “I wouldn’t trade places with President Coolidge today,” said McNeely. “I didn’t get but one hit. But boy, what did it mean. Yeah, I know it was a lucky one, but ain’t all hits lucky?”12

“We paid $50,000 for McNeely,” Harris told reporters, “and he repaid us today.”13

Back in Sacramento, planning began immediately for a celebration in McNeely’s honor. A parade with a marching band was scheduled as was a banquet. The new hero would be given a new $5,000 automobile as soon as he returned home. After basking in the accolades in the offseason, McNeely began 1925 as the presumptive regular center fielder for Washington. He even sent his first contract back unsigned in January, asking for more money.

He started the first five games of the season, but managed just three hits and lost playing time, first to Leibold and then to the newly acquired Joe “Moon” Harris. Harris would play either corner outfield position with Sam Rice moving to center. McNeely’s was the tale of three seasons. Going into the game of June 10, he was hitting .211, but after four hits that day, he went 16-for-29 over the next week to raise his average to .326. He reached a high of .353 after a 2-for-5 day on July 5. He made 72 of his 91 starts between June 10 and September 9.

McNeely was hitting .301 after a four-hit day on August 26, but the final month of the season was a disaster for him. He hit .212, going 14-for-66, from August 27 until the end of the season. Even though McNeely finished at a respectable .286, it’s no surprise that manager Harris chose to put Moon Harris in the starting lineup over McNeely in the 1925 World Series. Moon ended up as the Nats’ top hitter in a losing effort against the Pirates, with McNeely getting into just four of the seven games as a defensive sub and pinch runner. Perhaps McNeely’s worst statistic of 1925 was his base-stealing: He was successful in just 15 of 31 attempts during the season.

Still, McNeely was in center field for the most memorable play of the ’25 Series: Rice’s catch of Earl Smith’s long drive in Game Three. When Smith connected, Rice ran back toward the temporary bleachers, leaped, snagged the ball and fell head-first into the stands. He disappeared for at least 10 seconds before McNeely, who had just entered the game in center, pulled him out by his uniform jersey. Rice held the ball high and the out call was made. The Pirates were furious, but as Rice said for the rest of his life, when asked if he had held onto the ball, “the umpire said I did.” In a letter opened after his death, Rice insisted he never lost possession of the ball.14

That winter, McNeely’s father died after a long illness. William and Clare McNeely had been living with her parents in Alameda, south of Oakland on the San Francisco Bay, for the past decade. He was 77. Several weeks later, on February 3, Earl married Ethel Greenhalgh, whose family had moved to the Sacramento area from Minnesota 20 years earlier. Her mother had emigrated from Germany. Her father was a fruit farmer.15

Although the Nats fell to a disappointing fourth in 1926, McNeely had a bounce-back year. He didn’t start a game until May 1, but he got hot fast. After a 4-for-4 day on July 17, he was hitting .364, close to the league-lead. Even though he couldn’t sustain that pace, he never fell below .300 and finished at .303. He had the best game of his career at the plate on July 13: 5-for-5 with a double and four runs batted in, hitting lead-off. His base running improved, too, in ’26: He stole 18 bases and was caught just six times.

Despite his solid season, McNeely went into 1927 knowing he would not be a regular: Washington had acquired Tris Speaker to play center. McNeely did not make a start until April 28. By June 20, he had started just seven games. He started 10 straight games between June 21 and 28, but then didn’t start again until a month later. Still, hitting 4-for-9 after two days in the lineup raised his average to .315 on July 29. He got 14 starts in August, the last three at first base, a position he had played just once before in the majors. He finished 1927 with 300 fewer plate appearances than the year before, but hit .276.

That fall, he was traded to the St. Louis Browns with pitcher Dick Coffman for pitchers Milt Gaston and Sad Sam Jones. McNeely played more than he ever had. He led the league by being hit by eight pitches and in assists as a right fielder with 19. Otherwise, his 1928 results were far below his previous performance. At age 30, his .236 average and .299 on-base percentage spelled the end of his days as a regular. A .243 average in 69 games as a reserve in 1929 was hardly better (his OBP dropped to .272). He rebounded a bit in 1930, hitting his career average at .272 with a .340 OBP, and making himself useful by playing 27 games at first base. McNeely became a player-coach in 1931, but still started 26 games in the outfield.

The Browns released him to Milwaukee after the season, but he played just four games before the American Association team sold him to the Sacramento Senators. Back at home in the PCL, McNeely played in 100 games in 1932 and hit .281. On August 4, he took over as manager, replacing Buddy Ryan. He won his first game that day and the team went on a hot streak, winning 12 of 13. By season’s end, Sacramento had jumped from sixth to third place and was viewed as a contender for the PCL title in 1933. McNeely hit .308 in 94 games, but his Senators, commonly called the Solons, faded late and finished fourth at 96-85 in the long PCL season.

In February 1934, Sacramento’s longtime owner Lew Moreing was unable to repay a loan on which he had pledged the team as collateral. The bank foreclosed on Moreing and then sold the Solons to Earl McNeely for $135,000, to be paid in installments over three years.16 The purchase made McNeely, at 35, the nation’s youngest owner of a top-level minor league team. “I believe this to be the opportunity of lifetime,” McNeely said the day the deal closed. “Sacramento is a good baseball town…. The club has always been a money-maker.”17

His need to sell players to pay the bills didn’t help the team’s performance on the field. He stayed on as manager, while acting as team president, treasurer and business manager—a tall order. Several factors kept McNeely from financial success as an owner. He had no personal fortune. The Great Depression had driven down PCL attendance in general and Sacramento’s in particular (its 1934 average attendance was about 700). The Los Angeles Angels, picked in 2001 as the best minor league team of the 20th century, ran away with both halves of the season with a combined record of 137-50.18 Sacramento was 79-109.

Yet McNeely received little sympathy when he sounded an alarm at a PCL directors’ meeting in May 1935. He called for cuts in ticket prices and players’ salaries and for the league to play at a lower level than AA. Some of the other owners blamed McNeely’s financial trouble on the high salaries he had to pay the players optioned to Sacramento from Brooklyn, with whom McNeely had a working agreement.19

Sacramento had another awful season in 1935, finishing 75-100. When the bank that held the title to Moreing Field went into receivership, the Solons’ home park was sold for $15,000.20 To save money, McNeely let his new field manager go and returned to the dugout himself. That fall, McNeely and a representative of another bank, to which he owed the balance of the purchase price for the team, went to the annual minor league meeting in Dayton, Ohio, and sold off all the players they had under contract.21

McNeely accepted an offer to become the third base coach of the Washington Senators for 1936 under his old manager Bucky Harris. In December, knowing he wouldn’t be back, McNeely turned over what was left of the Solons to Branch Rickey and the St. Louis Cardinals. No money changed hands, McNeely said, with the Cards presumably settling the team’s debt.22

After two seasons as a coach in Washington, the Senators let him go, and McNeely was done with baseball. He returned to the Sacramento valley and went into the dried fruit business with his brother-in-law. He and Ethel had their only child, a daughter Carol, in 1939. McNeely also raised cattle on his farm in Orangevale and dabbled in real estate.

Becoming active in local affairs, he joined the volunteer fire department and later became director of the fire district. He ran unsuccessfully to be a county supervisor. He was the head of the Orangevale school board. “I wrote the checks, hired the teachers, hunted up the substitutes (and) worked on … introducing school buses,” McNeely wrote in a 1959 collection of reminiscences by longtime residents of Orangevale.23

The achievement of which he seemed most proud was his role in establishing American River Junior College in 1955. He served as founding member of the college’s board.24 American River, in northern Sacramento County, has grown into one of the largest two-year colleges in California with more than 35,000 students.

McNeely returned to Washington three times to participate in reunions of the 1924 World Series champs. The first time, in 1932, Griffith had to send him the air fare. He and his former teammates took part in a September 1951 re-enactment of the deciding game. The final gathering came in 1959, a year before the Griffith franchise’s final season in Washington.

McNeely spent his last years in his native Sacramento valley. He retired from business in 1959 and had become an avid golfer. After a long illness, he died of lung cancer on July 16, 1971. He is buried at Mount Vernon Memorial Park in Sacramento County.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Skylar Browning and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 U.S. Census, 1900, 1910 and 1920, accessed through www.familysearch.org.

2 John Drohan, “Senator Star Is Transit Man,” Boston Traveler, September 27, 1924, page unknown, accessed from McNeely’s clip file at the Hall of Fame’s research center.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Shirley Povich, The Washington Senators, (New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons,1954): 114-115.

6 Leo McClatchy, “Washington Is Ball Crazy,” (syndicated feature), (Reno) Nevada State Journal, September 2, 1924: 5.

7 Henry L. Farrell, United Press, “Giants Defeat Johnson.” (Madison) Wisconsin State Journal, October 5, 1924: 48.

8 Bill Corum, “Senators Win World Championship,” New York Times, October 11, 1924: 9.

9 Bucky Harris, “Plays That Count” AP Newsfeatures, (Long Beach, CA) Press-Telegram, April 13, 1954: 12.

10 Ibid.

11 Francis P. Daily, “Crazed by Thrills, Mad Mob Engulfs Heroes After Game,” Washington Post, October 11, 1924: 2.

12 “What Nats Say,”, Washington Post, October 11, 1924: 4.

13 “Team Spirit Won, Says Bucky Harris,” New York Times, October 11, 1924: 10.

14 Brian Cronin, “Did Sam Rice reveal a World Series Secret in a letter opened after his death?”, Los Angeles Times blog post, September 7, 2011, http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/sports_blog/2011/09/, accessed October 8, 2017.

15 1920 U.S. Census.

16 United Press, “McNeely, Sacs Manager, Buys Club Franchise,” Santa Rosa Press Democrat, February 15, 1934: 4.

17 “McNeely, Former Washington Outfielder, Becomes Sacramento Boss,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 15, 1934: 17.

18 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, “Top 100 Teams,” 2001, http://milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=1.

19 “Coast League Directors Go Into Pow Wow,” Ogden Standard Examiner, May 21, 1935: 10.

20 United Press, “Cardinals Get Moreing Field,” Oakland Tribune, January 7, 1936: 13.

21 United Press, “St. Louis Owns Senators Now,” Bakersfield Californian, December 13, 1935: 16.

22 Ibid.

23 Mark L. Pelesh, “Away Flies the Boy,” Hardball Times, October 15, 2015, https://www.fangraphs.com/tht/away-flies-the-boy/, accessed October 9, 2017; In addition to much about McNeely, Pelesh’s essay also includes a detailed look at Muddy Ruel’s career.

24 Email from Scott Crow, Public Information Officer, American River College, on October 17, 2017.

Full Name

George Earl McNeely

Born

May 12, 1898 at Sacramento, CA (USA)

Died

July 16, 1971 at Sacramento, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.