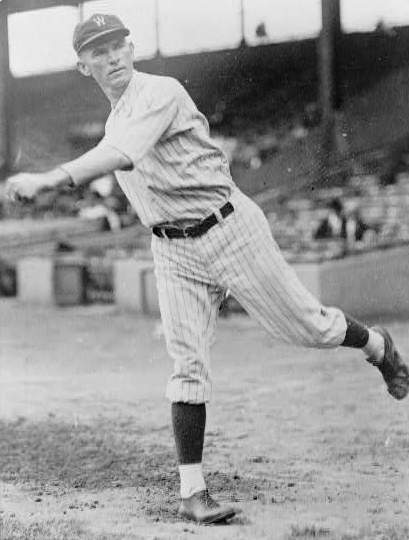

Tom Zachary

Tom Zachary pitched in the majors from 1918 through 1936, logging 186 victories.1 The Guilford College star — who took part in one of the greatest collegiate pitching duels ever waged — never played a minor league game, a rare occurrence in those days. He picked up three World Series checks and was on the World Champion Senators in 1924 and Yankees in 1928. In the postseason he had a lifetime 3-0 mark with a 2.86 ERA. In his most impressive regular season, he posted a 12-0 mark with the Yankees in 1929. No major leaguer has won more without a defeat in a season. However, with all those accomplishments, he is best remembered for delivering a low, inside fastball that Babe Ruth drove into the right field seats for his 60th home run in 1927.2

Tom Zachary pitched in the majors from 1918 through 1936, logging 186 victories.1 The Guilford College star — who took part in one of the greatest collegiate pitching duels ever waged — never played a minor league game, a rare occurrence in those days. He picked up three World Series checks and was on the World Champion Senators in 1924 and Yankees in 1928. In the postseason he had a lifetime 3-0 mark with a 2.86 ERA. In his most impressive regular season, he posted a 12-0 mark with the Yankees in 1929. No major leaguer has won more without a defeat in a season. However, with all those accomplishments, he is best remembered for delivering a low, inside fastball that Babe Ruth drove into the right field seats for his 60th home run in 1927.2

Jonathan Thompson Zachary was the seventh child born to Alfred and Mary E. (Guthrie) Zachary. He joined the family on May 7, 1896, on the family farm near Graham, North Carolina. Both his parents came from longstanding North Carolina families of Scotch-Irish decent. Tom attended school in Alamance County, graduating from high school in 1915. He went on to Guilford College, where he played baseball from 1916 through 1918. How many classes he attended is open to conjecture. A yearbook lists him as a sophomore in 1918. On the questionnaire he filled out for the Baseball Hall of Fame, it appears he listed his schooling as “6hrs” for his collegiate years.

On the diamond for the Guilford Quakers he played outfield and pitched. In 1916 he picked up wins over Trinity (twice) and Wake Forest. A left-handed batter, he played center field when not on the hill and batted .345, second to catcher Bill Futrell.3 The following year he teamed with future major-leaguer Tim Murchison to lead a powerful squad that went undefeated in the college ranks. Zachary was 4-0 on the hill but saw his batting average drop to .137.

He closed out his career in 1918 serving as team captain. In one of the greatest collegiate pitching duels ever waged, future major league pitchers Tom Zachary and George Murray faced off on April 6, 1918, at Guilford College. Murray was the star of North Carolina State University and would drive out four singles and steal a base against his opponent. Meanwhile Zachary collected two of his team’s six hits off Murray. The two men matched out for out over 16 innings. Murray amassed 20 strikeouts while Zachary fanned 14. The game, tied at 0-0, was finally halted after the 16th frame by the umpire, Sherwood Upchurch, on account of “haziness” even though the sun had not set. Many in the crowd of 700 were certain that Upchurch’s “appetite had run away with him and that he was no longer interested in baseball.”4

That tie and an earlier one-run loss to the University of North Carolina were the only blemishes on Zachary’s senior season. By now he stood 6-foot-1 and weighed 185. After the season, he signed up with the Red Cross for service during the war. He was in Philadelphia for training when he approached Connie Mack for a tryout with the Athletics.

Mack liked what he saw and gave lefty “Zach Walton” (Zachary’s alias) a start with the Philadelphia Athletics on July 11, 1918. Zachary supposedly used “Walton” to preserve his college eligibility if he chose to return after the war.5 He went three innings against the St. Louis Browns and left the field leading, 6-3; under the scoring rules of the day he received credit for the 8-5 victory. On July 20 he took the mound against the Cleveland Indians and worked the first five innings. Up 5-1 when Scott Perry relieved him, Zachary recorded his second win.

Zachary’s tenure with the A’s coincided with the issuance of a “work or fight” edict that would eventually shut down major league baseball in early September. A few days after his second appearance, the A’s left on a road trip with all roster players except “Zack Walton, who did not get as far as signing a contract with the A’s.”6

Zachary was tightlipped about his time with the Mackmen. Asked by a reporter a decade later about the experience, he simply said, “The less said about it, the better.”7 Zachary saw service in France with the Red Cross before being released in June 1919. Philadelphia had not placed him on their reserve list, making him free to sign with any team.

Zachary was signed by Clark Griffith and the Washington Senators. He debuted with an inning of scoreless relief in Chicago on July 18. He followed that up with two stints in St. Louis before earning his first start on July 27 at home against Philadelphia. Whether Mack recognized the former Zach Walton is uncertain. Certainly, the newspaper writers were of little help. Some writers used his initials, J.T., that first year but his name also appeared as Joe and Zeke in the press.8

Whatever name was attached to him the results were the same; he was pitching fine ball for a rookie. Writer Paul Eaton for The Sporting News went so far as to call him “a real find and a future star.”9 On September 11 he made his fifth start and lost, 5-0, to the White Sox despite surrendering only two earned runs. His ERA stood at 1.96 after the game. He made two more starts but only lasted a total of two innings and surrendered seven runs to raise his ERA to 2.92. That was still third on the team for pitchers with over 50 innings.

Zachary was the type of pitcher who did not have “a world of stuff,” but had more than enough on his fastball and curve to confuse hitters.10 While not blessed with Walter Johnson’s heater, he made up for it with a “puzzling change of pace and a good curve.” He had “a way of “slopping” the ball at the batters, slow and easy,” inviting them to take their cut.11

Sportswriter Herman Wecke used variations of the phrase “he ain’t got nothing” at least a half dozen times in an article to describe the frustration hitters felt.12 Zachary’s secret to success was that he rarely got ruffled. “All batters look alike to me. I don’t get scared in the pinch. When there’s men on base and the going gets tough that’s when I get good.”13

Zachary joined the Senators’ rotation in 1920 and compiled a 15-16 record with three shutouts. He led his team in wins and complete games and was second to Johnson in ERA. The following season Washington added lefty George Mogridge to the staff. The threesome of Johnson, Mogridge and Zachary would lead the team to the World Series in 1924.

The 1924 Senators sputtered early in the season and entered June under the .500 mark. They swept the Yankees in four games June 23-25 to move into first place. They faltered in early August but scratched their way back to the top and finished the season ahead of New York.

In the World Series Walter Johnson started Game 1 and fell victim to the Giants, 4-3. Zachary pitched eight strong innings in the next game but needed relief from Firpo Marberry when he tired in the ninth. Zachary had allowed two runs to tie the game when Marberry came in with two outs and fanned Travis Jackson to close the frame. The Senators pushed across a run in the bottom half for a 4-3 victory.

The game was exciting but free of disputes. It was what happened postgame that created a stir in the baseball community. The win was originally granted to Marberry and appeared that way in early box scores and in The Sporting News. After the game, noted sportswriter Frederick G. Lieb, who was chief scorer, “posted notice at press headquarters” that Zachary deserved the win based upon his strong eight innings.14 The decision was met with strong discussion throughout the nation’s press, but the decision stood, and Zachary was given the win.

The Senators were down three games to two when Zachary toed the rubber for Game 6 in Washington. He had the Giants batters muttering to themselves for the next two hours as he scattered seven hits. New York scored once in the first before taking the 2-1 loss. The Senators captured the title with a Game 7 win behind Walter Johnson.

The Senators brought in Stan Coveleskie and Dutch Ruether for the 1925 season, which made Mogridge the odd man out. The starting staff of Covey, Ruether, Johnson and Zachary, with relief help from Marberry, led the team to 96 wins and the league title. Zachary was the only one of the group to post a losing record, 12-15.

Seven of those losses came after August 9 and cost him a spot in the starting rotation against the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. He made only one appearance in the postseason, a lackluster relief showing in Game 5. That game started the Pirate comeback of three straight wins to win the crown.

In February Zachary was part of a four-player swap with the St. Louis Browns that sent Bullet Joe Bush to Washington. Manager George Sisler made Zachary his starter for the second game of the season in Chicago. It proved to be one of his worst outings ever. Four hits, two walks and two errors led to eight runs and the hook for Zachary with two outs. Undeterred, he tossed complete games in his next three starts and became the team’s ace. He led the Browns in starts and innings pitched, with 18 complete games for the seventh-place club.

Zachary was inconsistent during the spring of 1927 and found himself hitting the showers before the fifth inning on four occasions in May and June. The Browns front office shopped him around following a June 16 game where he allowed back-to-back first inning blasts to Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

On July 7 he was traded back to the Senators for pitcher Alvin “General” Crowder. Zachary picked up three wins but then went on a six-game losing streak in August and early September, which was followed by a string of no-decisions. On September 25 he shut out the Browns for his first win since August 4. His next start would be in New York on September 30.

Babe Ruth had 57 home runs entering the final series against the Senators. He smashed two homers and drove in six on September 29. The dingers tied his career high of 59 and he had two games left to set a new standard. Zachary had faced the Babe many times since 1919. The Babe had hit eight home runs off his offerings, including two earlier in the season. “But few recall how many times I struck ol’ Babe out.”15

Zachary claimed that pitchers always bore down when facing Ruth. He would joke that if pitchers had tried that “hard against everyone else, they would have pitched many of the weaker hitters out of the league.”16The Babe walked on four pitches in the first inning. He singled and scored on a Bob Meusel sacrifice fly in the fourth to cut the Washington lead in half. He singled and scored on a Meusel single in the sixth to tie the game. The game was still tied in the eighth when Mark Koenig slammed a one-out triple. Ruth connected on Zachary’s third pitch and sent the ball curving towards the right field corner. It settled into the seats “no more than a foot inside” fair territory according to Senators catcher Muddy Ruel and plate umpire Bill Dinneen.17 New York won the game, 4-2, sending Tom to his 13th loss of the year.

That September game proved to be the last time Zachary faced the Babe in the regular season. In 20 games with Washington the following season, he posted his highest ERA (5.44) and WHIP (1.656) since his first games with the A’s. The Senators placed him on waivers and the Yankees picked him up on August 23, 1928.

Herb Pennock was injured at the time and Zachary’s left arm was needed for the final pennant run. He twirled three complete game victories in six starts and turned in a relief appearance that would earn a save in today’s world. Tom also launched one of the longest home runs ever hit in Comiskey Park on September 21. The ball “landed in the fourth tier of the second deck in the right field stands.”18 He closed out the year with a 9-12 record and prepared for the World Series against the Cardinals.

Zachary started Game 3 of the Series against Jesse Haines. The Cardinals struck early by scoring twice in the first on three hits. Zachary settled down after that and allowed only one more run on the way to a 7-3 win. His seven strikeouts were the most he had recorded since August 4, 1925.

While the Yankees dropped from first place in 1929, Zachary completed his most noteworthy season statistically, with a 2.48 ERA as he went 12-0. His sparkling ERA was more than a run lower than any of his teammates and was lower than Lefty Grove’s 2.81.19 Although Zachary pitched only 119 2/3 innings, The Sporting News declared him the “A.L. Pitcher of Year” and noted he had the best “earned run average record.”20 (Modern encyclopedias recognize Grove as the ERA leader since Zachary did not pitch enough innings to be eligible under today’s rules.) Tom was especially tough on Cleveland; he shut them out twice and recorded four wins at their expense.

The 1920s were good to Zachary. The booming economy and his strong left arm brought him contracts of $10,000, which was easily twice what the average worker was making. He had a farm in Alamance County and played the role of gentleman farmer. An avid hunter, he enjoyed hunting trips for fowl and small game during the off-season.

Zachary struggled at the opening of the 1930 season. Plagued with poor control in his first three starts, he had a 4.86 ERA. The nickname “Old Tom” had been following him for several years. Now 33, he struggled in the chilly spring and fans wondered if age had caught up to him. He finally picked up a win on May 7 (his 34th birthday) when a three-run homer by Ruth helped him to an 8-7 win over Cleveland.21 The Yankees had seen enough and placed him on waivers. He was signed May 12 by the Boston Braves.

Zachary had struggled in the American League and was now headed to the National League, where the batters were tearing the cover off the ball. The Nationals ended the season with a cumulative .303 batting average, 15 points higher than the final number in the AL. The senior circuit batters hit .317 off “Old Tom”, but the wily veteran scattered the hits. In his first outing he gave up nine hits to the Giants but beat them, 4-1.

Zachary made 22 starts for the Braves and completed 10 of them. His 11-5 record was the highest winning percentage on the staff. At the plate he batted .241 and launched the last two of his six career homers. That fall he was part of an all-star group that went to Cuba. The 25 players split into two squads and played seven games against each other and two versus Cuban teams. Teamed with Giants Bill Terry and Carl Hubbell, Tom lost twice to the Americans.22

Zachary looked good the next spring in the Braves training games in Florida. If there was a bounce in his step, it could be attributed to his January 16 wedding to Etta McBane in Buncombe, North Carolina. The couple would have two children, Jonathan and Sally.

He faced the Yankees just before the team broke camp and fanned Ruth twice while allowing five hits.23 Performances like that earned him the nod for opening day against the Brooklyn Robins. The first four men he faced reached base. After a strikeout he issued his second walk and was sent to the showers. The Braves rallied to win but Zachary was looking at an 81.00 ERA.

Manager Bill McKechnie stuck with his veteran lefty and Tom responded with two wins including a shutout of the Robins in Brooklyn the following week. He would later add two shutouts over the Pirates. On August 22, he beat Pittsburgh, 2-1, to run his record to 10-8. The Braves went into a stunning freefall after that and only won six more games. Zachary took seven defeats in that span and finished at 11-15 with an excellent 3.10 ERA.

The Braves opened in Brooklyn in 1932. Like the previous season, the Dodgers (as they had become known once again following Wilbert Robinson’s retirement) treated Zachary rudely in his first start when they exploded for four runs in the seventh to send him to the bench. Zachary took a while to reach his form and had only three wins when July opened. After that he went 9-5 while dropping his ERA from 4.46 to 3.10. His record might have been much better had the Braves scored more than a measly nine runs for him in five August starts.

A 37-year-old Zachary went to spring training in 1933 and took longer than normal to work into shape. McKechnie did not use him in early exhibitions and for the most part “left him to his own devices” to work into shape.24 Zachary experienced a sore arm and was not ready to pitch until May 8, when he lost, 3-0, to Pittsburgh. Unlike the previous year, he had a very successful August when he won three games (two of them shutouts) and lowered his ERA nearly a full point. Working in relief and as a fifth starter, he finished the season 7-9.

The following year he rounded into form in spring training without any issues. Once again, his season opened in Brooklyn, where he tied, 1-1, on April 19. A week later he shut out the Dodgers at home, 2-0. Zachary’s success versus the Dodgers made manager Casey Stengel comment sarcastically about his team’s fortunes. “Tom Zachary… how old is he, 60 or 61? He’s pitched two ball games against us… and we have slaughtered him to the extent of one run.”25

Unfortunately for Tom, there were other teams in the league. After a couple of road losses he was sent to the end of the bench. The Braves released him unconditionally on May 28. Ten days later he was signed by Stengel for his pitching staff. Zachary would remain in Brooklyn until April 1936. He appeared in 48 games and posted a 12-18 mark. He closed out his career with the Phillies in 1936 with an 0-3 mark.

Tom and Etta settled into life on the farm with the children. Jonathan attended the University of North Carolina, where he lettered playing first base for the Tar Heels. The soft-spoken Zachary was “part of the everyday scene in Graham. He was not pretentious… and wore plain farmer’s clothes more than anything else.”26 Etta was involved in the social scene around Graham. She had a marvelous green thumb and won awards for her flowers.

As time went on Tom found himself being invited to Old Timers’ games in New York and Washington and around the Carolinas. In 1948 he was in Yankee Stadium on June 13 for Babe Ruth’s final appearance, when his number 3 was retired. A two-inning old-timers’ game was held following Ruth’s speech and Tom’s team lost, 2-0, to the 1923 Yankees.

In 1956 he made an appearance on Ed Sullivan’s “Toast of the Town” where he discussed Ruth’s sixtieth home run. His life slowed considerably in 1967 when he suffered a mild stroke. He shook off the effects of that attack but was hit with a more severe stroke on January 8, 1969. He died in the hospital in Burlington, North Carolina, on January 24 when a massive stroke took his life.27 He was laid to rest in the Alamance Memorial Park in Burlington. In addition to his wife and children, he was survived by three grandchildren.

In 1966 Zachary was inducted into the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame along with race driver Lee Petty. He was the fourth baseball player to join the ranks, following the Ferrell brothers (Rick and Wes) and Enos Slaughter. In later years he would be joined by General Crowder and pitcher Ernie Shore, who had preceded him at Guilford College.28

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Warren Corbett.

Notes

1 He is tied with Jimmy Key for 153rd place in wins by pitcher, but he will likely be passed by Jon Lester in the 2019 season.

2 Gayle Talbot, “Writer Recalls Ruth’s Home Run of Zachary,” The Daily News-Times (Burlington, North Carolina), September 15, 1953: 5.

3 “Baseball Season at Guilford a Success,” Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, May 7, 1916: 21.

4 “Not One Run in Sixteen Frames,” News and Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina), April 7, 1918: 14.

5 “Lank” Leonard, “Ryan and Zachary Must Have Been Born Under a Lucky Star,” Brooklyn Citizen, September 19, 1928: 9.

6 “Want to Finish the Season Before Obeying Order,” The Evening News (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), July 24, 1918: 5.

7 George Kirksey, “Southpaw May Save Yankees,” Manitoba (Winnipeg) Free Press, October 4, 1928: 20.

8 Years later a story surfaced that his name was really Thomas Jonathan Jackson Zachary and that he’d been named after Stonewall Jackson from the Civil War. The Sporting News, August 29, 1929: 3.

9 Paul W. Eaton, “Rube Schauer Gets Another Trial at it,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1919: 3.

10 Billy Evans, “According to Billy Evans,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1926: 7.

11 Damon Runyon, “Three Pitched Balls Gives Marberry Victory in Second Series Tilt,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minn.), October 6, 1924: 10.

12 Herman Wecke, “Zachary in his Twelfth Year in Majors Pitcher in 12 Games, Without Losing One,” The Sporting News, January 23, 1930: 5.

13 Kirksey, Manitoba Free Press.

14 “Official Scorer Posts Award to Tom Zachary,” The Morning Herald (Uniontown, Pa.), October 7, 1924: 11.

15 Bill Hunter, “Former Major League Pitching Great Tom Zachary Dies at 72,” The Daily News-Times, January 25, 1969: 14.

16 Don Bolden, “Spring Training Brings Major League Memories to Graham’s Tom Zachary,” The Daily News-Times, March 26, 1954: 8.

17 “Gayle Talbot, “Writer Recalls Ruth’s Home Run Off Zachary,” The Daily News-Times, September 1, 1953: 5.

18 Bolden, “Spring Training Brings Memories”.

19 Modern record books and online sources list Grove as the 1929 ERA Leader because they use the criterion of pitching one inning or more for each game on the schedule.

20 “Veteran Tom Zachary of Yankees Was Leading A.L. Pitcher of Year,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1930: 5.

21 Hugh S. Fullerton, Jr. “Ruth’s Homer with Two Men on Helps Yanks Win,” The Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), May 8, 1930: 19.

22 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball, A Statistical History, 1878-1961, (Jefferson, NC.: McFarland, 2003), 188-89.

23 “Tribe Routs Yanks in Last Tilt, 9-2,” The Boston Globe, March 23, 1931: 11.

24 James C. O’Leary, “Braves, Yanks Renew Series,” The Boston Globe, March 23, 1933: 18.

25 Tommy Holmes, “Zachary, Like Betts, is ‘Easy to Hit’ But Still Dodgers Fail,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 27, 1934: 22.

26 Hunter, “Pitching Great Dies”.

27 Ibid.

28 https://www.ncshof.org/page/show/3187260-baseball-last accessed on July 11, 2019.

Full Name

Jonathan Thompson Walton Zachary

Born

May 7, 1896 at Graham, NC (USA)

Died

January 24, 1969 at Burlington, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.