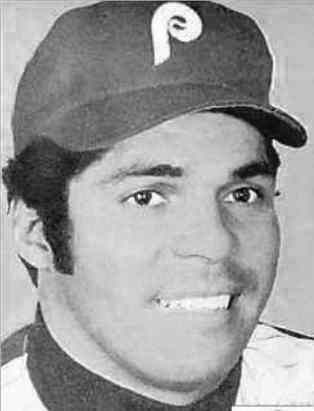

Sam Parrilla

When Sam Parrilla got the chance that every minor-leaguer hopes for, he thought of his father. But more than paternal pride ran through his mind; baseball’s indestructible link between fathers and sons sparked memories for the Puerto Rican native upon joining the Philadelphia Phillies at the beginning of the 1970 season. “My father, he’s a fanatic on baseball,” said Parrilla. “He used to take me to [Dodgers games at] Ebbets Field and to the parade grounds [sic] at Prospect Park. I always loved [Gil] Hodges, the way he played. I liked his style, his power. I dreamed of being a big league ballplayer, and for seven years I’ve waited for the opportunity.”1

When Sam Parrilla got the chance that every minor-leaguer hopes for, he thought of his father. But more than paternal pride ran through his mind; baseball’s indestructible link between fathers and sons sparked memories for the Puerto Rican native upon joining the Philadelphia Phillies at the beginning of the 1970 season. “My father, he’s a fanatic on baseball,” said Parrilla. “He used to take me to [Dodgers games at] Ebbets Field and to the parade grounds [sic] at Prospect Park. I always loved [Gil] Hodges, the way he played. I liked his style, his power. I dreamed of being a big league ballplayer, and for seven years I’ve waited for the opportunity.”1

It was an opportunity that lasted 11 games for the outfielder, who enjoyed an 11-year career in the minor leagues with some standout seasons.

Born on June 12, 1943 in Santurce, Puerto Rico, Samuel Parrilla Monges’s parents were Samuel Parrilla Vega and Emma Monges Ayala. The family’s ancestors were from Spain.

After moving to Brooklyn, Parrilla graduated in 1961 from John Jay High School, where he had played football as well as baseball. The Yankee Rookies, a program to develop young players, brought Parrilla on the team in the summer of 1961. It was their last season after a 22-year run. That team, coached by Arthur Dede, also included Steve Dillon.2

“There’s something really interesting about my dad that I had to confront. He had to lie about his ethnicity during his career because there was a fear that Puerto Ricans were not exalted at the time,” explains his daughter, actress Lana Parrilla, star of the ABC prime time show Once Upon A Time. “They weren’t given the same opportunities as Irish, Italian, or black players in the 1960s. Our family derives from Puerto Rico. But any time he spoke Spanish on the field or in the locker rooms, there was grief. For my father to have a shot, he had to lie about his ethnicity. So, the pronunciation of our name was ‘Pah-rill-ah.’

“Often, people asked me why my name wasn’t pronounced ‘Pah-ree-ah.’ When my acting career started to take off, I was in my early 20s. I changed it to ‘Pah-ree-ah.’”3

Discovered by scout José (Pepe) Seda, Parrilla signed his first pro contract with the Cleveland Indians organization.4 His pro career began in 1963 with the Dubuque (Iowa) Packers of the Class A Midwest League. The 5’11, 185-pound outfielder played in 118 games, batted .240, and tallied 51 RBIs. There were occasional examples of Parrilla’s power — 18 doubles, three triples, and 10 home runs.

It was the beginning of a minor-league journey that sent Parrilla across the country from Pawtucket to Portland — 11 teams, six leagues, and three levels of play (A, AA, AAA). He ended his career in the AAA Mexican League with the Chihuahua Dorados in 1973.

Parrilla played his first five years and part of the sixth for the Indians organization. With Burlington (North Carolina) of the Class A Carolina League in 1964, he got more opportunities (135 games) as his batting blossomed. Parrilla broke .300 for the first of four seasons, hitting .315, drawing 91 walks, and knocking in 77 runs. He also led the league in triples (14). After the season, the Greensboro Daily News named him to its league All-Star team.5

In the winter of 1964-65, Parrilla returned to his native land to play winter ball for the first of six seasons. He hit .227 with no homers and 7 RBIS in 75 at-bats for the Arecibo Lobos. Back in the States, 1965 brought a change to Parrilla — two changes, actually. He was initially promoted to the AA Reading (Pennsylvania) Indians in the Eastern League, but his 1964 average dropped steeply, to .244 in 53 games. He found his groove with the Salinas Indians in the Class A California League, batting .299 in 43 games.

After another winter with Arecibo (7-24-.233 in 146 at-bats), Parrilla returned to the Eastern League for 1966. Cleveland’s affiliate there had become Pawtucket, Rhode Island. There was more playing time — 113 games — but he couldn’t break .250 at the plate. Parrilla hit .242 with 8 homers and 45 RBIs while striking out 91 times.

A good winter season with Arecibo ensued: 5-29-.281 in 231 at-bats, the most he ever received in Puerto Rico. The summer of 1967 brought a jump from AA to AAA, an improvement at the plate, and a shift in parent teams for the Brooklyn-raised prospect. Early in the season, he was with the Yankees’ affiliate in the International League, the Syracuse Chiefs. He batted .125 in eight games and then rejoined the Indians system (implying that he might have been on loan to Syracuse). Parrilla played 85 games for the Portland Beavers in the AAA Pacific Coast League. He didn’t quite break .300, but he got fairly close with a .283 average to go with five homers and 29 RBIs.

During spring training that year in Florida, Parrilla met his wife, Dolores Dee Azzara, while she was traveling with her mother on vacation. “They met at a pizzeria,” reveals Lana. “All the guys were checking out my mom, a beautiful Sicilian woman with olive skin and long black hair. The guys were making a bet on who would ask her out. My dad made a beeline straight for her. He asked her out and he was smitten. They learned that they were both from Brooklyn. His family lived on a street around the corner from my mother’s aunt in the same neighborhood, literally a block away from each other. I have one sister, Deena, and a half-sister from a previous relationship of my father’s.”6

Parrilla did not play in Puerto Rico in the winter of 1967-68. Despite his reasonably good ’67 season, he was sent back to the Eastern League once more in 1968. Cleveland had yet another new location for its EL affiliate, Waterbury (Connecticut). He hit merely 5-26-.202 in 117 games and was released.7

Parrilla returned to Puerto Rico for the 1968-69 season, but with a new club, the San Juan Senadores. Though he batted just .255 in 192 at-bats, he reached career highs on the island with 10 homers and 32 RBIs.

The Phillies organization picked up Parrilla, but he had to take yet another step backwards in 1969, to the Carolina League, where he had played five years previously. He saw action in 95 games and nearly reached the elusive .400 benchmark, batting .383. Though he’d shown moderate power before, he built on his winter showing for San Juan by slugging 28 homers and driving in 85 runs. Sportswriter Bob Moskowitz of the Daily Press (covering the Newport News area) declared that he voted for Lou Quinn of the Salem Rebels for “player of the year” because Parrilla, whom he described as a “late-season sensation,” didn’t play in enough games. Quinn, indeed, won the league’s MVP award with impressive stats, but fewer home runs (20) and RBIs (74) than Parrilla, and a .314 average in 119 games.

After the season, the Phillies announced that Parrilla and teammate Greg Luzinski were getting promoted to the 40-man big-league roster.8 His second winter with San Juan ended with a 3-12-.255 line in 110 at-bats.

Parrilla competed for and won a major-league job in spring training 1970. A spot was open in the Phillies’ outfield because Curt Flood, who’d been traded to Philadelphia in October 1969, was sitting out after launching his challenge to baseball’s reserve clause. Larry Hisle, who’d had a fine rookie year in 1969, was a lock. Johnny Briggs became a starter, and so did Byron Browne, who’d also come over from St. Louis in the Flood deal. The fourth outfielder was Ron Stone. Longshot Parrilla emerged from a group that also included Oscar Gamble, Joe Lis, and Scott Reid.9

After Parrilla officially made the big club’s roster, he felt like a weight had been lifted. In a game late in the exhibition season against the Minnesota Twins, his relaxed state of mind led to a star performance — he knocked a home run in the sixth inning and sparked an eighth-inning come-from-behind rally. The Twins led 3-2 when Parrilla singled; the Phillies scored two runs on a stolen base, an error, and two singles. “When I went up to hit in the sixth, I was more relaxed than I’ve been all spring,” Parrilla explained.10

Parrilla batted .125 in his 11-game stint for the Phillies. He started three times in left field; his other eight appearances came as a pinch-hitter. His first hit was a single off Mike McCormick in a start on May 3 at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. His only other hit was a pinch double off Claude Osteen as the Phillies faced the Dodgers at Connie Mack Stadium on May 8. After Parrilla’s shot off the right field wall, that was all for Osteen. But after a walk and a flyout, reliever Jim Brewer ended the inning by picking Parrilla off second base.11

In mid-May, trying to snap a losing streak that eventually reached 10 games, the Phillies sent Parrilla to the Eugene Emeralds in the Pacific Coast League while bringing up Oscar Gamble from Eugene.12 Parrilla hit briskly in the PCL, compiling a line of .334, with three home runs and 34 RBIs in 67 games.

Because of a salary dispute, Parrilla skipped winter ball again in the 1970-71 season.13 In December 1970, Phillies management traded him, southpaw Grant Jackson, and utiilityman Jim Hutto to the Baltimore Orioles for International League MVP outfielder Roger Freed. Baltimore also got $100,000.14

Jackson played for the Orioles in 1971; Parrilla and Hutto went to Triple-A Rochester.15 It was a noteworthy year for Parrilla, who had 11 homers, 70 RBIs, and a .333 average. Facing the Tidewater Tides in the International League playoffs, the Red Wings found victory through Parrilla in Game Five.

Initially unaware that bonus money came with advancing to the Little World Series, Parrilla learned this financial detail by accident. “We were postponed for two straight nights, and while we were waiting for the rain to stop, Sam overheard some of the players talking about getting a share of the gate receipts from the first four games if we reached the Little World Series,” recalled former Red Wings skipper Joe Altobelli nearly a quarter-century later.16

Whether that influenced his performance or not, Parrilla smashed two home runs for four RBIs in the 8-5 victory. And so, the Red Wings advanced to face the American Association champs, the Denver Bears, whom they beat in seven games for the Little World Series title.

Parrilla had a last go-round in the Puerto Rican Winter League in 1971-72, posting a line of 3-7-.333 in 60 at-bats for the Caguas Criollos. In 1972, he faced a severe decrease in playing time because of an ankle injury.17 He played in 51 games and hit .261 for Rochester; he then returned to the Cleveland organization after his contract was sold to Portland in July. Parrilla threatened to quit at first but reconsidered, one reason being that the resulting suspension would have made him ineligible to play winter ball (the irony was that he did not do so again).18 For the Beavers, he played in 43 games, with marks of 7-18-.288. That September, he joined the Caribbean All-Stars, one of five teams playing in the Kodak World Baseball Classic, a round-robin baseball tournament at Honolulu Stadium. The other four were the Hawaii Islanders and the champions of the three Class AAA leagues. Yet despite the high talent level, attendance was very poor and this tournament was a one-off.

After his short stint in the Mexican League in 1973 (1-26-.376 in 38 games), Parrilla retired from baseball.

Sam and Dolores divorced in the early 1980s, but the family remained close. “My father was a very fun-loving family man and protective of us,” says Lana. “He loved his mother and his daughters and made sure the family did things together. He loved children and dogs. Most people didn’t know that he was very funny. He had incredible comic timing and he liked to portray characters. He was a bit of a prankster, but in a comical way, not a scary way. He was also an artist who drew very well. He built things and was very creative with his hands.”

“His favorite actor was Robert De Niro. He loved Bruce Lee movies, Westerns, and anything by Martin Scorsese. We saw three or four movies every weekend. It’s where I got my love of film and acting. He nurtured that and probably created it. I also got a lot of inspiration from my Aunt Candy — my mother’s sister.” Candice Azzara is a character actress with many roles to her credit.

“Even when he didn’t have much, my father was a mindful, generous man. Selfless. Conscientious. I got that from both of my parents. That’s why volunteer work is a big part of my life. One time, my father let a homeless man into our house and use our bathroom because the man needed a place to clean up.”19

Parrilla’s death is one of baseball’s tragedies. He was shot on February 9, 1994 at the corner of Hoyt and Pacific Streets in Brooklyn; he died in Long Island College Hospital that same day. The murder happened because of an argument resulting from a car accident. A jeep with several passengers crashed into Parrilla’s car; three days later, as agreed, he went to Hoyt and Pacific to get money for damages. The shooter, who was 15 years old, was tried as a juvenile. “It’s unfortunate because the laws were different,” says Lana. “The shooter got six years. It’s not enough time. We’re happy the laws have changed.”20

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Puerto Rican Winter League statistics: Courtesy of SABR member Jorge Colón Delgado, who oversees the database originally compiled by José A. Crescioni.

Mexican statistics: Pedro Treto Cisneros, editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano, 11th edition. Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 2011.

Notes

1 Stan Hochman, “Break Out the Chianti — Sammy Made It!”, Philadelphia Daily News, April 2, 1970: 56.

2 Matt Rothenberg, “‘Rookie’ Teams Of New York City Fostered Prospects For Dodgers, Yankees,” National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum (https://baseballhall.org/discover/rookie-teams-of-new-york-fostered-prospects-for-dodgers-yankees).

3 Telephone interview with Lana Parrilla, June 29, 2018. The self-imposed description of his ethnicity is why there are incorrect descriptions in some sources of Parrilla as being “of half Puerto Rican and half Italian descent.” For example, the “Chianti” in the headline of Stan Hochman’s article (note #1) is a clear allusion.

4 Samuel Parrilla Biographical Summary, Samuel Parrilla File, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

5 “[Steve] Whitaker Rated Top Slugger,” The Sporting News, September 19, 1964: 38.

6 Telephone interview with Lana Parrilla.

7 “[Dick] Allen brother on Phils’ roster,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, October 29, 1969: 49.

8 “Phils Promote Sam Parrilla, Greg Luzinski,” Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia), October 29, 1969: 21.

9 “Speaking of Sports,” Hazleton (Pennsylvania) Standard-Speaker, February 5, 1970: 28.

10 “Sam Parrilla More Relaxed After Phils Cut,” Associated Press, Lebanon (Pennsylvania) Daily News, April 2, 1970: 25.

11 “Dodgers’ Extra-Base Hits, 4 Runs in 12th Beat Phils, 8-4,” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1970: 53.

12 “Phils Call Gamble,” Pittsburgh Press, May 15, 1970: 40.

13 Miguel Frau, “[Roberto] Clemente On, Off San Juan Roster During 24-Hour Span,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1971: 55.

14 Bill Conlin, “[Wally] Moses, Freed Fill Phils’ Christmas Stocking,” Philadelphia Daily News, December 17, 1970: 56.

15 “Birds Swap Roger Freed And Get Grant Jackson,” Associated Press, York Daily Record, December 17, 1970: 28.

16 Bob Matthews, “Parrilla gave it his all for 1971 team,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, March 27, 1994: 63.

17 Craig Stolze, “Wings Will Get Better,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 7, 1972: 45.

18 “Coast Toasties,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1972: 38.

19 Telephone interview with Lana Parrilla.

20 Ibid.

Full Name

Samuel Parrilla Monge

Born

June 12, 1943 at Santurce, (P.R.)

Died

February 9, 1994 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.