September 11, 1882: Tony Mullane throws the first no-hitter in American Association

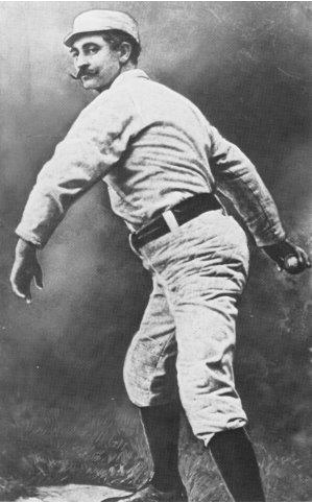

If you had mentioned the name Tony Mullane to his teammates and opponents during his baseball-playing days, many differing opinions of his actions might come to mind. For example, Mullane, who came to the United States with his family from Ireland in 1864, was handsome and is said to be one of the reasons that ladies’ day games became popular in the 1880s. He was also willing to bend the rules of baseball, pitching above the shoulder at a time when this was considered an illegal pitch; he was also considered to be tightfisted with his money, often wearing clothes until they became raggedy. But one thing that was universally acknowledged about him was that Tony Mullane was one of the dominant pitchers in professional baseball of his time, posting 284 career wins.

If you had mentioned the name Tony Mullane to his teammates and opponents during his baseball-playing days, many differing opinions of his actions might come to mind. For example, Mullane, who came to the United States with his family from Ireland in 1864, was handsome and is said to be one of the reasons that ladies’ day games became popular in the 1880s. He was also willing to bend the rules of baseball, pitching above the shoulder at a time when this was considered an illegal pitch; he was also considered to be tightfisted with his money, often wearing clothes until they became raggedy. But one thing that was universally acknowledged about him was that Tony Mullane was one of the dominant pitchers in professional baseball of his time, posting 284 career wins.

After a five-game pitching debut with the Detroit Wolverines of the National League in 1881, during which his won-loss record was 1-4, Mullane appeared to be a long shot to succeed in professional baseball. But despite his less-than-impressive first season, the Louisville Eclipse of the American Association sought his services as a change pitcher and first baseman, and signed him for the 1882 season, the Association’s inaugural season. The circuit adopted the same dimensions for the pitcher’s box (6 feet by 4 feet) and the distance from the front of the pitcher’s box to the center of home plate (50 feet) as the rival National League.1 Mullane, having pitched in the National League in 1881, had already adjusted to the distance to home, and compiled a 30-24 won-lost record with a 1.88 ERA in 1882.

Mullane was involved in two particularly noteworthy games during the 1882 season. First, on July 18 he used both hands to throw to batters, (throwing left-handed to left-handed batters and right-handed to right-handed batters), becoming professional baseball’s first ambidextrous pitcher, in a 9-8 loss to the Baltimore Orioles.2 On September 11 he pitched a no-hit game against the Cincinnati Red Stockings, the Association’s first.

In the no-hit game, Mullane’s pitching opponent was Will White of the Red Stockings, an accomplished hurler in his own right, who would win 229 games over a 10-season career with a lifetime 2.28 ERA; in 1882, he would go 40-12 with a 1.54 ERA. The game was played at Bank Street Grounds in Cincinnati before 1,922 fans with the temperature in the high 60s on a day when Cincinnati was beginning to close in on the first American Association pennant.3 Cincinnati, the home team, opted under the rules of the day to bat first.

Cincinnati’s leadoff batter, Joe Sommer, drew a base on balls. But he was doubled up on an outfield fly, his mistake compounded when the next batter, Hick Carpenter, reached base on a two-base error and went to third on a passed ball; no damage was done, as Carpenter was left stranded at third. After the visiting Eclipse went out in order in the first, the Red Stockings failed to capitalize on a muffed fly by John Reccius in center field in the second inning; in the bottom of the inning, the Eclipse wasted a single by Mullane when he was thrown out by catcher Pop Snyder trying to advance on a passed ball.

The third and fourth innings were uneventful for both teams, and the Red Stockings were retired in order in the fifth and sixth. The Eclipse, however, in the sixth inning, provided some excitement when Samuel Maskrey, known by his middle name, Leech, reached on an error by Red Stockings third baseman Carpenter. Reccius hit to right field, and he and Maskrey both advanced a base on Harry Wheeler’s throw to home. With no outs and runners at second and third, a big inning appeared imminent, but pitcher White of the Red Stockings bore down and retired Pete Browning, Guy Hecker, and Dan Sullivan to end the threat.

After a scoreless seventh frame, the Eclipse scored two runs in the eighth. Leadoff batter Bill Schenck reached on an error by shortstop Chick Fulmer. Maskrey flied out but Reccius swatted a three-base hit to right center, scoring Schenck, and scored himself when right fielder Wheeler threw wild attempting to get Reccius at home. The next batter, Pete Browning, made history of his own when he became the first American Association player to reach base safely but getcalled out for being an illegal baserunner.4 Browning, who had a pulled leg muscle, had requested that someone run for him when he was hitting, his teammate Hecker. With Hecker standing behind him ready to run to first when the ball was hit, Browning stroked a hit to right field. But in his excitement at getting a hit, Browning began to run to first. Hecker, confused at seeing Browning begin to run, stopped and ran off the field, while Browning continued to first, and eventually was declared out for being an illegal baserunner. Browning batted .378 and won the Association’s batting title by a whopping 36 points in 1882. The lost hit affected his career batting average by one point (.341), preventing him from tying Dan Brouthers (.342) for the highest career batting average among players active primarily before 1893, when the pitching distance was lengthened.5

Sommer struck out to lead off the Cincinnati ninth, but got to first when catcher Sullivan missed the third strike. Wheeler flied out and Carpenter forced Sommer at second. With two out, Reccius muffed a fly ball by Snyder, and Carpenter went to third and Snyder to first. However, Dan Stearns forced Snyder at second, ending the game. Both White and Mullane pitched well, and umpire Mike Walsh was praised for his fairness in calling balls and strikes. the game was completed in 1 hour and 40 minutes. No matter what people thought of the antics of Mullane over the years, it cannot be denied that pitching a no-hit game in your first full year of professional baseball is a great way to start your career.

This article was published in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin. To read more Games Project stories from this book, click here.

Notes

1 Eric Miklich, “The Pitcher’s Area,” 19cbaseball.com/rules.html

2 Jerry Grillo, “Mullane Goes Both Ways,” Bill Felber, ed., Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2013).

3 “Mullane’s Mash,” Cincinnati Tribune, September 12, 1882.

4 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball (New York: Penguin Books, 1997), 175.

5 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Louisville Eclipse 2

Cincinnati Red Stockings 0

Bank Street Grounds

Cincinnati, OH

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.