July 18, 1882: Tony Mullane goes both ways

You have to wonder what kind of mind-altering substance could have inspired the Baltimore Sun to claim that its city’s ballclub was “now the equal of some of the best nines” in the American Association.

You have to wonder what kind of mind-altering substance could have inspired the Baltimore Sun to claim that its city’s ballclub was “now the equal of some of the best nines” in the American Association.

Seriously? The Baltimores had just lost three straight, had gone 0-for-June, and were planted in the league basement with a 6–30 record as the Eclipse team of Louisville pulled into town for a four-game mid-July series in 1882.

When the Baltimores built a 7–1 lead after three innings of the July 18 series opener, the Sun’s hubris did not seem so misplaced. For the fans at Newington Park that Tuesday afternoon, this was a rare sight. But in a few moments they would witness something stranger than a Baltimore lead.

The Eclipse’s dashing young pitcher, Tony Mullane, playing his first full major-league season (and en route to the first of five consecutive 30-victory seasons) wasn’t used to being bullied this way, certainly not against the likes of the lowly Baltimores.

The right-hander was getting frustrated so he did something no one had ever seen in a big-league game before. He switched pitching hands.

“Mullane, of the Eclipse club, changed hands in the fourth inning and pitched with his left,” the Sun reported, retiring the Baltimores, “in good style.” Mullane had just become the first ambidextrous pitcher in major-league baseball history.

The 23-year-old Irish-born Mullane was really just beginning an incomparable career as one of the 19th century’s dominant pitchers and great characters, a handsome, free-spirited rogue and one of the game’s most versatile athletes.

A strong-armed pitcher who completed 468 of the 504 games he started, Mullane had injured his right arm in a distance-throwing contest a few years earlier, so he’d taught himself to throw left-handed. That’s why on July 18, 1882, he was capable of giving his self-made sinistrality a test run against a Baltimore team that ranked among the weaker ones in the American Association.

The weakling Baltimores were halfway through a season that would end with a miserable 19–54 record and a team batting average of .207. Oddly, they were actually pretty good in close games, finishing 8–5 in one-run contests. They had a solid rookie outfielder, Tom Brown, who would bat .304 in ’82.

The Eclipse was 20–18 coming into the game en route to a third-place finish (42–38–1) in the sixteam league. The Eclipse had a superstar rookie outfielder, Pete Browning, who would lead the American Association with a .378 batting average that year (the first of three batting titles for the original “Louisville Slugger”). And they had a soon-to-be- 30-game winner in Mullane.

But the Louisville-based team had lost four straight before arriving in Baltimore and seemed ready to roll over again as the home team took a 3–0 lead in the first, highlighted by Brown’s tworun triple. They made it 7–0 after two, with Charlie Householder, Doc Landis, Henry Myers, and Charlie Waitt crossing the plate.

Mullane’s ambidextrous turn in the fourth may have lit a little fire for the Eclipse, who scored four runs in the fifth, “by heavy batting, aided by wild throwing,” the Sun reported. And Mullane mostly kept Baltimore off balance, switching back and forth, throwing right-handed to left-handed hitters and lefty to righties.

The Eclipse knotted the score, 8–8, in the eighth on a home run by Guy Hecker.

But in the bottom of the ninth, the Baltimore crowd saw something that was almost as rare as an ambidextrous pitching performance—a home run by first baseman Householder, his only one of the season (he hit four in his career). It was “a tremendous hit over centre-field, nearly to the fence,” according to the Sun. “He was surrounded by the crowd and received an ovation.”

Less than two months later, on September 11, Mullane pitched a no-hitter against the Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first of its kind in the American Association.

But he is still remembered most for switching hands in a game he lost. He was not the last to pitch with both hands, nor was that game in Baltimore the last time he tried. He did it twice more: On July 5, 1892, and again on July 14, 1893, throwing left-handed in the final inning of a 10–2 loss to the Chicago Colts.

He wasn’t even the last Louisville pitcher to do it. On May 9, 1888, Elton “Icebox” Chamberlain, a right-hander, threw shutout ball with his left hand over the final two innings of an 18–6 win over the Kansas City Cowboys. (Chamberlain would pitch ambidextrously one more time, for Philadelphia’s American Association team in 1891.) Two years after Mullane did it, on June 16, 1884, right-handed Larry Corcoran, pitching for the Chicago White Stockings, became the first ambidextrous hurler in the National League, alternating arms in a 20–9 loss to the Buffalo Bisons.

Only two other players in major-league history are known to have tried since then. On September 28, 1995, Greg Harris, a natural right-hander, pitched lefty to two batters in a 9–7 loss to the Cincinnati Reds. (There are disputed reports that George Wheeler pitched ambidextrously for Philadelphia in the late 1890s.) In 2015, Pat Venditte made his major-league debut with the Oakland A’s. He is the first pitcher since the 19th century to “switch-pitch” regularly, typically using whichever hand gives him the platoon advantage against the hitter.

But Mullane had set the standard. He wound up with 284 victories in his 13-year career, second all-time in wins among pitchers not in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Mullane won fame and earned infamy away from the playing field, challenging the reserve clause, jumping from team to team (he played for eight different clubs), and earning a suspension in the prime of his career (1885), which almost certainly cost him the victories he needed to reach 300. (He also sat out part of another season to protest a pay cut.)

Nicknamed the Count and the Apollo of the Box, Mullane was considered so handsome that teams would schedule Ladies Day when he was pitching. In other ways, however, Mullane was a less attractive figure. In 1884 he pitched for the Toledo Blue Stockings, where his catcher was the African American Moses Fleetwood Walker. Mullane called Walker the best catcher he ever worked with, but also said he disliked blacks and refused to take signals from Walker. So Mullane threw whatever he wanted, without warning, crossing up (and occasionally injuring) Walker and hurting the team in the process.

Mullane played every position except catcher at one time or another. He was also a fine ice skater and boxer, known for putting his pugilistic skills to the test on a ballfield.

There is no record of whether his right cross was better than his left hook, however.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

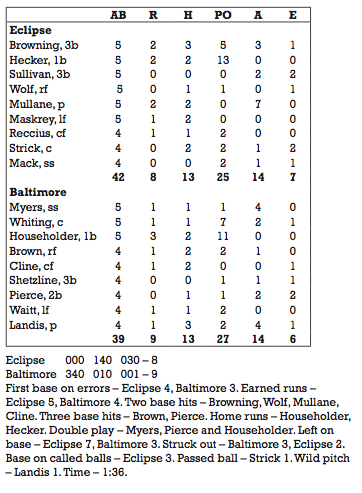

Lord Baltimores 9

Louisville Eclipse 8

Newington Park

Baltimore, MD

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.