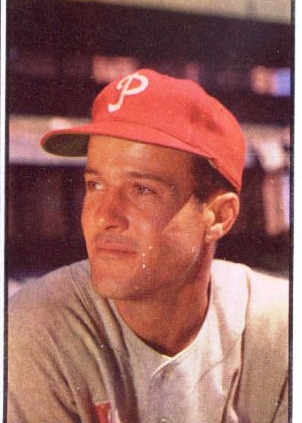

Connie Ryan

Although he had far from the best year of his career in 1948, Connie Ryan was a valuable utility infielder for the Boston Braves that season — primarily backing up incumbent Eddie Stanky (and later his replacement, Sibby Sisti) at second base. Ryan was an intense competitor as well as an occasional sparkplug for the National League pennant-winners, and could be counted on to play solid defense. He was also not averse to a scuffle now and then.

Although he had far from the best year of his career in 1948, Connie Ryan was a valuable utility infielder for the Boston Braves that season — primarily backing up incumbent Eddie Stanky (and later his replacement, Sibby Sisti) at second base. Ryan was an intense competitor as well as an occasional sparkplug for the National League pennant-winners, and could be counted on to play solid defense. He was also not averse to a scuffle now and then.

Those qualities stood out to former New York Giants manager Mel Ott, who had scouted Ryan before bringing the young infielder to the major leagues in 1942. “From all the tales that have come on here before Ryan he is a competent and aggressive agent,” read one unattributed 1942 newspaper account found in Hall of Fame files. “Ott saw him [Ryan] in New Orleans — his home town too — and admired his fighting spirit as well as his ability. He is a peppery, chip-on-shoulder player like [Dick] Bartell or John McGraw.”

Ryan’s teammates typically viewed him as pleasant and gentlemanly. Another 1942 account claimed that Connie was “much more articulate than the average rookie getting his first major league chance, and so humble that he ministers to everybody from the bellhops to the bat-boy.”

Yet Ryan’s competitiveness occasionally boiled over. In 1940, while playing second base in the minor leagues for Savannah, he had a scuffle with future major league teammate Eddie Stanky, who was then the second baseman for the opposing Macon team. As Ryan recounted years later, “Every time that I went out to my position, I noticed that my glove was in right field instead of near second base [fielders routinely left their gloves on the field between innings in those days]. I figured somebody was kicking it out there, so I watched — and it turned out to be Stanky kicking it.

“I ran over and took a swing at him, and we got into a little scrape before other players tore us apart. The next thing we knew, we were on the way to the Savannah jail. He was fined $100 and I got off for nothing, for some reason. We got back to the park about a half hour later and finished the game.”

While Ryan reportedly was “not overly proud of his pugilistic exploits,” he was a part of two other incidents during his career that received significant attention from the press. During a 1950 game while with the Reds, he was covering first base on a bunt when Philadelphia’s Willie Jones spiked him. When the same thing happened at second base a few weeks later, Ryan went after Jones because Ryan “figured [Jones] was doing it deliberately. I missed with a right and then somebody broke us up.” The two became good friends when Ryan joined the Phillies a couple years later, and Ryan eventually smoothed things over with Stanky as well.

In addition, when Ryan was managing in Corpus Christi after his major league career was over, he “set off a real donnybrook” in August 1955 when he “unloaded a right cross to the jaw of Pitcher [sic] Bill Bagwell” of Port Arthur. The incident took place after Bagwell had thrown two pitches close to a Corpus Christi batter following some apparent taunting by Corpus Christi’s Rene Vega following a home run.

These episodes notwithstanding, Ryan was remembered as “a good team player” and as “an excellent baseball man.” Such compliments were traceable to his rookie season of ’42, when an article commented on how he was “an eager and enthusiastic youngster, though a pleasantly restrained and polite one, looking much like [boxing great] Billy Conn and exuding Conn’s engaging sureness in himself.”

In fact, when he first came to the majors that spring with the New York Giants, the 5’11”, 175 lb. Ryan was reportedly so deferential that he referred to teammates, including Carl Hubbell, as “Mister.” At one point, manager Ott took Ryan aside and told him that everyone with the team would prefer that Connie use their respective first names. With that, one newspaper reporter remarked: “Suddenly you remembered who Connie Ryan reminded you of. Another quiet, courteous gentleman from New Orleans, named Mel Ott.”

Cornelius Joseph Ryan was born on February 27, 1920 in New Orleans. He was of Irish heritage and had two younger brothers; his father did administrative work for a New Orleans barge line.

Connie’s interest in sports was evident from an early age, and the young man played for local American Legion teams in 1935 and 1936. Ryan also saw action on the baseball, football, basketball, and track teams at Jesuit High School in New Orleans, the same school attended by future major league All-Stars Rusty Staub and Will Clark. In addition to becoming the first person ever to receive a full baseball scholarship to Louisiana State University — where his future Braves double-play partner, shortstop Al Dark, would star a few years later. Ryan also played semipro ball in 1938 for Angier, North Carolina, and the next year was with a developmental team in Colonial Heights, Virginia.

Ryan’s love of the game led him to leave LSU over the Christmas break of his sophomore year to play pro ball for the Atlanta Crackers in the Southern League. He was reportedly conflicted between a career in baseball or in the legal profession, but elected to chase grounders. While he was optioned to Savannah of the Sally League during that first season, Ryan was sent back to Atlanta in 1941 after batting .316 in 113 games for Savannah. During the ’41 season with the Crackers, Ryan batted .300 in 151 games with 83 runs batted in and was chosen as Atlanta’s Most Valuable Player.

During that period, player-manager Mel Ott felt that the Giants were neglecting to scout talent from his hometown of New Orleans. The team signed Lucius Caruso, a 19-year-old first baseman also from Jesuit High School, as the first New Orleanian on Ott’s watch. “We’ve been missing a lot of good talent here, but from here out our scouts will spend a lot of time in New Orleans and we’ll get more boys like Connie Ryan,” Ott later said.

The Giants purchased Ryan’s contract from Atlanta on August 7, 1941, and soon began preparing him to be the team’s second baseman in place of Burgess Whitehead, who left the team after a subpar 1941 season. According to an unattributed February 28, 1942 article: “The kid from Atlanta reminds some of Billy Conn, others of Larry Doyle, but despite the ballyhoo, he has managed to remain Cornelius Ryan, Jr., with a great deal of dignity for a 21-year-old. The boy moved stylishly at second base yesterday, but it’s no time to put the plug in for him. If he’s overly praised now, it might have to be said next week that Ryan doesn’t look like Ryan did last week. In brief, he’s just a rookie.”

In spite of the high expectations, Ryan played in only 11 games in 1942, batting .185 with two RBIs. He also committed an alarming four errors. “The boy is very nervous, all tightened up,” said a newspaper account of May 20, 1942. “That is plain, and there is no need to go beyond that into the play by play of the rookie’s misadventures. Summing up, Ryan has not hit, has not come through on double-plays and has not fielded with assurance.”

While noting that Ryan had performed all of these tasks well in the minor leagues, sportswriter Joe King went on to say: “There’s a lot of ball-player in him — it will come out again in awhile, but the Giants need it now.” The popular perception was that Ryan suffered a nervous breakdown, similar to what Mickey Witek — “the breakdown boy of 1940” — had endured two years prior.

One bright spot in a mostly forgettable abbreviated rookie season was the time Ryan almost turned an unassisted triple play against Pittsburgh. On May 12 at the Polo Grounds, the Pirates’ Frank Gustine hit a line drive to Connie in the seventh inning. Rather than touching second base to force Johnny Lanning and then tagging out Pete Coscarart, who were both running on a 3-and-2 pitch, Ryan instead threw to shortstop Billy Jurges, who forced Lanning and tagged Coscarart for the triple play. “Just a few steps,” said one report, “and Ryan could have retired the side [himself].”

His part in one of baseball’s rarest feats notwithstanding, New York soon optioned Ryan to Jersey City of the International League for more seasoning. And after hitting a disappointing .241 in 112 games there, the highly-touted second baseman never made it back to the Giants. On April 27, 1943, Ryan was traded to the Braves along with catcher Hugh Poland in exchange for six-time All-Star catcher Ernie Lombardi. There was some controversy surrounding the deal, with rumors that Boston may have received a secret $30,000 as part of the trade. Yet it was well known that Lombardi was not content with the Braves, and, as one reporter put it, Boston had an incentive to deal “a bachelor who might be called to war any day.”

It was a great move for Ryan, as he was the regular second baseman in 1943 for the sixth-place Braves club managed by Casey Stengel and Bob Coleman (who took over during Casey’s convalescence from a broken leg). In 132 games during his first full major league season, Ryan batted only .212. He did, however, hit a two-run pinch-hit homer against his former Giants teammates: “With the count two balls and one strike he got hold of an outside pitch and away went the ballgame.”

Apparently over his nervousness, Ryan’s hitting and fielding the next year improved dramatically, and he was chosen for the first and only time to the National League All-Star team. Ryan played all nine innings of the 1944 All-Star Game at second base, got two hits, and had the lone stolen base of the contest during a 7-1 National League victory at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field.

Exactly two weeks later, and less than two months after the Allied invasion at Normandy, Ryan enlisted in the Navy on July 25, 1944. At the time, his batting average of .295 was second on the team, he was tied for the N.L. lead in stolen bases with 13, and his fielding average was on pace to lead the circuit as well. Duty called, however, and so like many ballplayers during World War II, he traded one uniform for the other while at the top of his game. He wound up playing in just 88 contests that year before heading off for service, yet he made enough of an impression that he still received votes for NL Most Valuable Player that October.

Ryan served overseas during the remainder of the war, and was discharged in January 1946 having missed one-and-a-half seasons. Returning to the Braves, he stepped right back in as the team’s starting second baseman for the 1946 and 1947 seasons. The club was much improved; under new manager Billy Southworth, it rose to fourth place in ’46 and third in ’47. Ryan was a steady contributor on defense and at bat showed surprising pop — finishing among team leaders in doubles both years and placing third in RBIs with 69 in the latter campaign. However, when the team traded for Dodgers second baseman and sparkplug Eddie Stanky shortly before the 1948 season began, Connie became a reserve.

Ryan did play briefly in the 1948 World Series, appearing in two games and striking out in his only at-bat. Still, he was appreciated largely for his defense rather than for his hitting. As baseball historian Arthur Schott noted, “He didn’t hit for a big average (.248 in his career), so he had to be an outstanding fielder to stay in the majors as long as he did.”

Connie is well remembered for an incident that took place on September 29, 1949 at Braves Field, during his last year with Boston. During a meaningless end-of-season Ladies Day game, as rain fell and the skies darkened at Braves Field, Ryan donned a raincoat while waiting to bat in the on-deck circle. Home plate umpire George Barr saw Ryan’s coat and threw him out of the contest for his not-so-subtle suggestion that the game be called.

As Ryan later recounted: “They wouldn’t listen to us when we hollered at them from the bench that it was raining too hard to play. They wouldn’t even take a hint when we built a little fire out of programs and newspapers in front of the dugout. I thought I’d try to convince them some other way, that’s all.”

Minus his raincoat, Ryan remained with the Braves until May 10, 1950, when he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds for catcher Walker Cooper — an excellent veteran player whom Boston manager Billy Southworth had previously managed in St. Louis. Ryan started at second base for the Reds through 1951, and proved pretty crafty himself. During a game against the Giants on May 6 of ’51, for instance, he infuriated New York manager Leo Durocher when he successfully pulled the “hidden-ball trick” in the 10th inning of a 4-3 contest at the Polo Grounds. New York’s Whitey Lockman was tagged out at second base, though he would later argue that his foot was still on the base. “It fooled all the Giants, most of the Reds, the entire press box…perhaps every one of the 27,766 fans, and even an umpire who was a few feet from the scene,” said a newspaper report.

The Reds were a dismal sixth-place team, and despite his sharp baseball mind and solid day-to-day contributions — he led the 1951 team with a career-high 16 home runs — Ryan was one of the casualties as the organization sought to rebuild. On December 10 of ’51, Cincinnati traded Connie along with Smoky Burgess and Howie Fox to the Philadelphia Phillies for Andy Seminick, Eddie Pellagrini, Dick Sisler, and Niles Jordan. Phillies manager Eddie Sawyer was thrilled to acquire Ryan, saying: “I think Ryan at second with Granny Hamner at short will make a dandy keystone combination.”

It did, for a while. Connie hit another 12 homers in 1952, scored a career-high 81 runs, and he and Hamner both turned nearly 100 double plays. A highlight of Ryan’s time with Philadelphia was getting six hits in six at-bats during a game at Pittsburgh on April 16, 1953, making him the first Phillies player — and just the 31st in major league history — to accomplish what at the time was a big league record. This was the springboard for another strong year at the plate, as Ryan hit .296 through the first half of the year. But Philadelphia still left him unprotected later that summer, and when released on August 25 he was picked up on waivers by the Chicago White Sox. He played in only 17 games for Chicago (hitting just .222), then was traded back to the Reds with Rocky Krsnich and Saul Rogovin for Willard Marshall on December 10 of ’53. His only appearance in his second stint with Cincinnati, on April 19, 1954, turned out to also be his last game in the big leagues. He finished his 12-year career in the majors with 988 hits in 1,184 games, 56 home runs, 381 RBIs, and a .248 batting average.

Not surprisingly, Ryan’s reputation as a tough, heads-up ballplayer helped him to stay in the game. He played the rest of the ’54 season in the minor leagues for Louisville of the American Association, then in 1955, played and managed for Corpus Christi of the Big State League. After appearing in 45 games as player-manager for Austin of the Texas League in 1945, his professional playing days were over, but his managerial career was just beginning. Ryan’s other minor league skippering stints were with Seattle of the Pacific Coast League in 1958, Oklahoma City of the American Association in 1962, and Twin Falls of the Pioneer League from 1968 through 1970. Ryan was also an interim manager twice in the major leagues: for 27 games with Atlanta in 1975 and for six games with Texas in 1977. Both times the full-time position went to other men, perhaps because Connie’s no-nonsense approach worried management. “I am not concerned with anybody’s feelings,” he was quoted as saying, while the Braves’ interim manager. “I would pinch-hit for my mother to win a ball game.”

He never achieved fame as a manager at the big-league level, but Ryan did have some other memorable moments while in the non-playing ranks. He was a coach on the 1957 Milwaukee Braves team that won the World Series over the Yankees, and discovered future All-Star Vida Blue while scouting for the Athletics in the 1960s. And perhaps most excitedly, while serving as third-base coach of the Atlanta Braves in 1974, Ryan was the first man to shake Hank Aaron’s hand as Aaron rounded third base after setting the new all-time home run record of 715. As a tribute to all his achievements, Ryan was also chosen for both the New Orleans and the Louisiana Sports Halls of Fame.

After his coaching and scouting days were through, Ryan kept busy in church and civic groups during his retirement. He was a member of the executive board of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the New Orleans Diamond Club, and the Major League Players Association, According to the New Orleans Times Picayune, he was also active in the St. Mary Magdalen and St. Clement of Rome Catholic churches.

When Ryan’s name comes up today, it’s usually by a fan recounting for the umpteenth time the tale of Connie and his raincoat. It’s a fun image, but it doesn’t do full credit to the man. Ryan could joke with the best of them, but most of the time he was all business whether in the field, at the plate, or making decisions in the dugout. “Connie was a great guy,” said Mel Parnell, who pitched for the Red Sox while Ryan was in Boston with the Braves. “He was serious when it came to baseball, and he was a great student of the game.”

Connie Ryan died on January 3, 1996 at East Jefferson General Hospital in Metairie, Louisiana following a heart attack. He was 75 years old, and was survived by his wife, Lorraine Chalona Streckfus Ryan, four children, six grandchildren, and a great-grandchild. He is buried in Metairie Cemetery.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Biographical and statistical information from websites baseball-reference.com, baseball-almanac.com, and baseballlibrary.com.

Clippings from Connie Ryan’s player file at the Hall of Fame:

Cincinnati Reds biography, 1951.

“Connie Ryan Discharge Today,” January 17, 1946.

“Connie Ryan, Veteran of Baseball Battles, Could Rub Some of His Fight on Braves,” December 9, 1956.

“Cooper for Connie Ryan,” May 19, 1950.

Daley, Arthur. “Triple Play by Ryan and Jurges Marks 7-3 Success for Ott Team,” May 13, 1952.

Daniel, Dan. “Daniel’s Dope,” April 29, 1943.

“He Reminded You of Someone,” Giant Jottings, March 18, 1942.

King, Joe. “Ryan Touted Early as Rookie of ’42: But New Giant Retains His Poise,” February 26, 1942.

King, Joe. “Nerves Still Wrecking Ryan’s Play: Another Rest May Solve His Problem,” May 26, 1942.

King, Joe. “Ryan Relieved of Keystone Job on Giants: Witek Takes Over for Jittery Recruit,” March 1942.

King, Joe. “Unassisted Triple Play — Almost: Few Steps Would Have Turned the Trick,” May 13, 1942.

King, Joe. “Rookie Ryan Key Player of Giant Infield: Ott Banks on Youth To Fill Keystone Spot,” February 24, 1982.

King, Joe. “Nerves Still Wrecking Ryan’s Play: Another Rest May Solve His Problem,” May 20, 1942.

Lewis, Ted. Obituary. “Player, coach, scout Ryan dies at age 75.” New Orleans Times Picayune, January 4, 1996.

Minor league data, apparently from the 1978 Texas Rangers media guide, provided by the Hall of Fame.

Minshew, Wayne. “Trade Winds Send Players Into Motion,” September 20, 1975.

Mitchell, Jerry. “Ott Is Sold on Connie Ryan: Rookie Second Baseman’s Fielding Impresses,” 1942.

“New Orleans Boys Get Break from Mel Ott,” February 4, 1942.

Obituary, “Connie Ryan 75,” Sports Collector’s Digest, February 2, 1996.

Obituary. “Infielder ‘Connie’ Ryan II, N.O. baseball legend, dies,” New Orleans Times Picayune, January 4, 1996.

“Ott at Last Gets Slugger He Long Has Been Seeking: Mel’s Infield Reserve Strength Reduced to Bartell by Trade,” April 28, 1943.

“Redleg in a Rhubarb: One of the reasons Connie Ryan has become Cincy’s ace second sacker is because he once went to bat in a raincoat when he was with Boston.”

Roeder, Bill. “Giants Not Amused by Connie’s Con Game,” May 7, 1951.

“Ryan of Braves Goes Into Navy,” July 25, 1944.

“Ryan Is 31st To Get 6 Hits”

“Ryan First Phil To Get ‘6 For 6,’” April 17, 1953.

“Sawyer High on Ryan’s Hustle,” Boston Daily Record, March 17, 1952.

Smith, Ken. “Ryan Homer in 9th Shames Giants, 3-2,” Daily Mirror, April 29, 1943.

Tagliabue, Emil. “Ryan’s Right Cross Starts Corpus Christi Mass Fight: Park Police Stop Melee Between Teams,” August 17, 1955.

United Press, “Braves Sign Connie Ryan To Coach at 3d,” October 6, 1956.

“Walker Cooper for Braves’ Ryan,” May 11, 1950.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Cornelius Joseph Ryan

Born

February 27, 1920 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

January 3, 1996 at Metairie, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.