Bruce Petway

In 1952, a panel of 31 Negro baseball experts selected the greatest Negro ballplayers of all time. The catchers chosen for the first team were Josh Gibson and Biz Mackey. The second-team catchers were Roy Campanella and Bruce Petway.1 In the words of historian James A. Riley, Petway was “the first great receiver in black baseball history.”2

In 1952, a panel of 31 Negro baseball experts selected the greatest Negro ballplayers of all time. The catchers chosen for the first team were Josh Gibson and Biz Mackey. The second-team catchers were Roy Campanella and Bruce Petway.1 In the words of historian James A. Riley, Petway was “the first great receiver in black baseball history.”2

Bruce Franklin Petway was born December 23, 1885, in Nashville. His brother Howard was born the year before. Their parents, David and Elizabeth Petway, had 13 children (nine living) at the time of the 1900 U.S. Census. As a stationary engineer, David operated and maintained industrial machinery. Bruce and Howard played baseball in Nashville’s Sulphur Spring Bottom League. They formed a battery: Howard was a left-handed pitcher and Bruce was his catcher.3 Bruce was known by his nickname, Buddy.4

Bruce attended the Meharry Medical College in Nashville but left to pursue a career in professional baseball.5 He played on a team in Cairo, Illinois,6 and then moved north to Chicago where he joined Howard on the Leland Giants. On July 2, 1906, the Chicago Inter Ocean reported: “The Leland Giants, with the Petway brothers from Nashville, Tenn., as their battery, defeated the Frankfort (Ind.) team at Auburn Park, 5 to 1.” Bruce collected four hits in the game.

By August 1906, Bruce had left Howard in Chicago and joined the Cuban X Giants in Philadelphia.7 Howard pitched for the Nashville Standard Giants in 1907, and moved to the St. Paul (Minnesota) Gophers the next year.8 Bruce was the starting catcher for the Philadelphia Giants from 1907 to 1909, and turned heads with his outstanding play.

In a game against the Cuban Stars in August 1908, Bruce threw out six baserunners attempting to steal second base.9 He resembled Lou Criger, one of the best defensive catchers in the American League, in ability and build.10 Both men had strong, accurate throwing arms and were slender, especially for a catcher, about 5-foot-10 and 160 pounds. Petway, though, was a faster runner. In December 1909, he was rated the top catcher in Negro baseball by sportswriters Harry Daniels and Jimmie Smith. “Petway … is the best throwing and base-running catcher colored base ball has seen,” wrote Daniels.11

Rube Foster, the great pitcher and manager, recruited Bruce Petway and John Henry Lloyd to play for the Chicago Leland Giants in 1910. Petway and Lloyd were teammates on the Cuban X Giants and Philadelphia Giants; they “were very close, like brothers,” said Lloyd’s wife Nan.12 Lloyd, a shortstop and future Hall of Famer, would be compared to the great Honus Wagner.

Unofficially, the 1910 Leland Giants compiled a phenomenal record of 123 wins and 6 losses through games of September.13 The team played in Cuba in the fall and returned to the United States, but Petway and Lloyd remained in Cuba to play for the Havana Reds in a series of exhibition games against the Detroit Tigers and Philadelphia Athletics. In 11 games against these major-league opponents, Lloyd batted .405 (15-for-37), and Petway hit .257 (9-for-35), and as catcher, tallied 40 putouts, 16 assists, one error, and one passed ball.14 The Havana Reds won six of the 11 contests (3-3 against the Tigers and 3-2 against the Athletics). American League umpire Billy Evans, who umpired several of these games, was impressed with Petway’s work behind the plate. “I have worked back of few better catchers than Petway,” said Evans.15

Arriving late to Cuba, Ty Cobb played in just two games for the Detroit Tigers against Petway and the Havana Reds. The Tigers lost the first one, 3-0, on November 28; Cobb, after drawing a walk, was thrown out by Petway when he attempted to steal second base.16 This feat made Petway famous. In the second game, on December 4, Cobb and the Tigers clobbered the Reds, 12-4.17 It is known that Cobb did not steal a base in two games against Petway, but unknown how many times he attempted to steal. Even before Petway stopped Cobb on the basepaths, the Washington Evening Star reported that Petway was “making a great impression” in Cuba, and the Detroit Free Press said Petway was “probably one of the best catchers in the world, who could be in the big leagues were it not for the color line.”18

Rube Foster formed his own team, the Chicago American Giants, in 1911, and Petway was the American Giants’ primary catcher from 1911 to 1918. On a typical day, he “instilled fear into the hearts of […] runners by his pegging, holding [them] close to the bags at all times.”19 Petway was one of the first catchers to throw from a squat, without rising.20 He could also throw runners out from his knees.21 He did not throw a “heavy” ball; his snap throws were “light,” easy for an infielder to catch.22 Petway would sometimes intentionally drop the ball, to entice a runner to leave his base, and he was an uncanny judge of foul popups.23

Petway contributed on offense, too. Batting leadoff on July 30, 1913, he smacked two singles and a double, stole a base, and scored two runs off pitcher “Cyclone Joe” Williams, a future Hall of Famer.24 The American Giants earned a 9-5 victory that day over the New York Lincoln Giants, who were managed by John Henry Lloyd. The following year Lloyd was Petway’s teammate on Foster’s squad. Walter “Judge” McCredie, manager of the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League, extolled the pair:

“There are two ballplayers of black color whom I think are, in their respective positions, as good as anyone else in the world. These two are Lloyd who played short last spring for the Chicago Colored Giants and Petway who caught for the same team. I think Lloyd is another Hans Wagner, while Petway is easily one of the greatest backstops in the game.”25

On April 2, 1914, Petway slugged a double, triple, and home run versus the Portland Colts of the Class B Northwestern League.26 His game-ending single on August 25, 1914, drove in the winning run in the second game of a doubleheader against the Indianapolis ABCs.27 On August 18, 1916, Petway tripled and homered in the American Giants’ 17-7 rout of the Lincoln Giants.28 He missed several months of the 1914 and 1915 seasons with a sore arm.29

On April 2, 1914, Petway slugged a double, triple, and home run versus the Portland Colts of the Class B Northwestern League.26 His game-ending single on August 25, 1914, drove in the winning run in the second game of a doubleheader against the Indianapolis ABCs.27 On August 18, 1916, Petway tripled and homered in the American Giants’ 17-7 rout of the Lincoln Giants.28 He missed several months of the 1914 and 1915 seasons with a sore arm.29

With Foster’s blessing, Petway left the American Giants in 1919 to join the newly formed Detroit Stars, managed by Pete Hill, a slugging center fielder and future Hall of Famer. Petway got off to a fast start on his new team: On May 11, 1919, he went 5-for-5 with a double and triple in the Stars’ 18-3 drubbing of the Cleveland Giants.30 The next year the Stars joined the newly formed Negro National League.

Petway remained with the Detroit Stars through the 1925 season and was playing manager of the team from 1922 to 1925. On the Stars, he was credited with developing a pair of eventual Hall of Famers, pitcher Andy Cooper and outfielder Turkey Stearnes.

Petway married Mamie Biassey in Philadelphia in 1907.31 The couple divorced about 1919, and he married Emma Jefferson in Lake County, Indiana, in 1920.32

Petway retired from professional baseball in 1926, at the age of 40. He and Emma settled in Chicago, and he took a job managing kitchenette apartments.33

The great backstop died on June 28, 1941, in Chicago, at the age of 55. In the words of his obituary, “Death ‘tagged’ Buddy Petway … at the Cook county hospital where he had been sick a month — but Buddy went out smiling just as he took things in life.”34

In 2006 Petway was one of the preliminary candidates considered for election into the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues, but he was not chosen for induction.35 His career batting average, estimated to be .232 by Seamheads.com,36 was probably not high enough. But there should be no question that Petway was one of the greatest defensive catchers in baseball history.

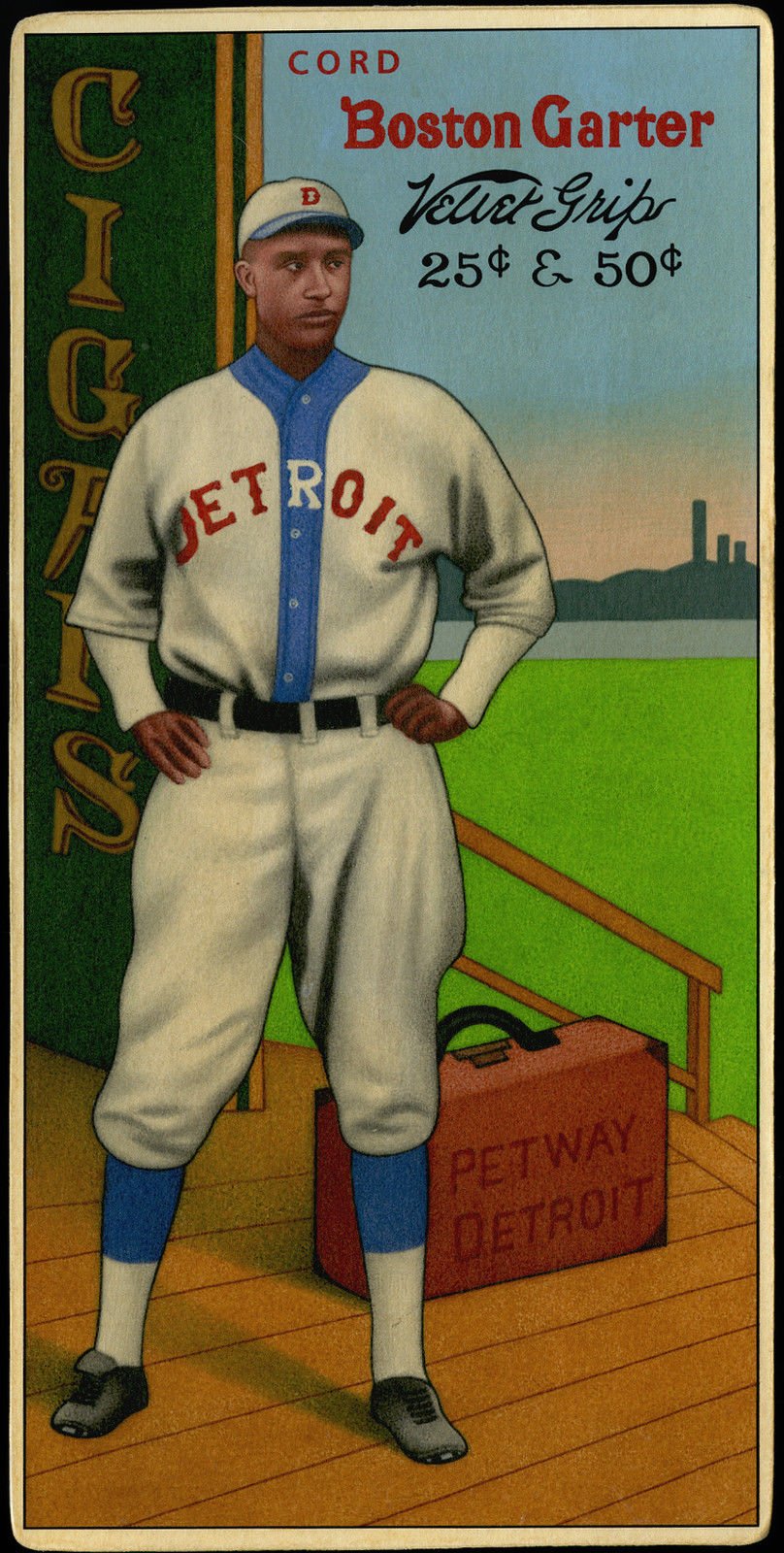

Photo credit

Image courtesy of Helmar Art Cards.

Notes

1 Robert Charles Cottrell, The Best Pitcher in Baseball: The Life of Rube Foster, Negro League Giant (New York: New York University Press, 2001), 182.

2 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 624.

3 Nashville Globe, March 25, 1910.

4 Ibid.

5 Chicago Defender, July 12, 1941.

6 Nashville Globe, March 25, 1910.

7 Brooklyn Standard Union, August 9 and 20, 1906; Chicago Tribune, September 3, 1906.

8 Nashville Globe, February 22 and June 14, 1907; Chicago Inter Ocean, May 7, 1908.

9 Brooklyn Standard Union, August 23, 1908.

10 Detroit Free Press, August 10, 1909.

11 Indianapolis Freeman, December 25, 1909.

12 Wes Singletary, The Right Time: John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 22.

13 Cottrell, 59.

14 Sporting Life, December 31, 1910, and January 21, 1911.

15 Washington Evening Star, March 13, 1912.

16 Detroit Free Press, November 29, 1910.

17# Detroit Free Press, December 5, 1910.

18# Washington Evening Star, November 23, 1910; Detroit Free Press, November 27, 1910.

19 Seattle Star, April 5, 1913.

20 Chicago Defender, July 12, 1941.

21 John B. Holway, Blackball Tales (Springfield, Virginia: Scorpio Books, 2008), 5.

22 Pittsburgh Courier, April 30, 1927.

23 Pittsburgh Courier, March 1, 1930.

24 Chicago Tribune, July 31, 1913.

25 Oakland Tribune, December 29, 1914.

26 Oregon Daily Journal, April 3, 1914.

27 Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1914.

28 Chicago Tribune, August 19, 1916.

29 Chicago Defender, April 25, 1914, and August 28, 1915.

30 Chicago Defender, May 17, 1919.

31 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Marriage Index, 1885-1951, at Ancestry.com.

32 Indiana, Marriage Index, 1800–1941, at Ancestry.com.

33 Chicago Defender, July 12, 1941.

34 Chicago Defender, July 12, 1941.

35 http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/2006_Special_Committee_on_the_Negro_Leagues_Election. Accessed January 18, 2016.

36 http://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?ID=624. Accessed January 18, 2016.

Full Name

Bruce Franklin Petway

Born

December 23, 1885 at Nashville, TN (US)

Died

June 28, 1941 at Chicago, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.