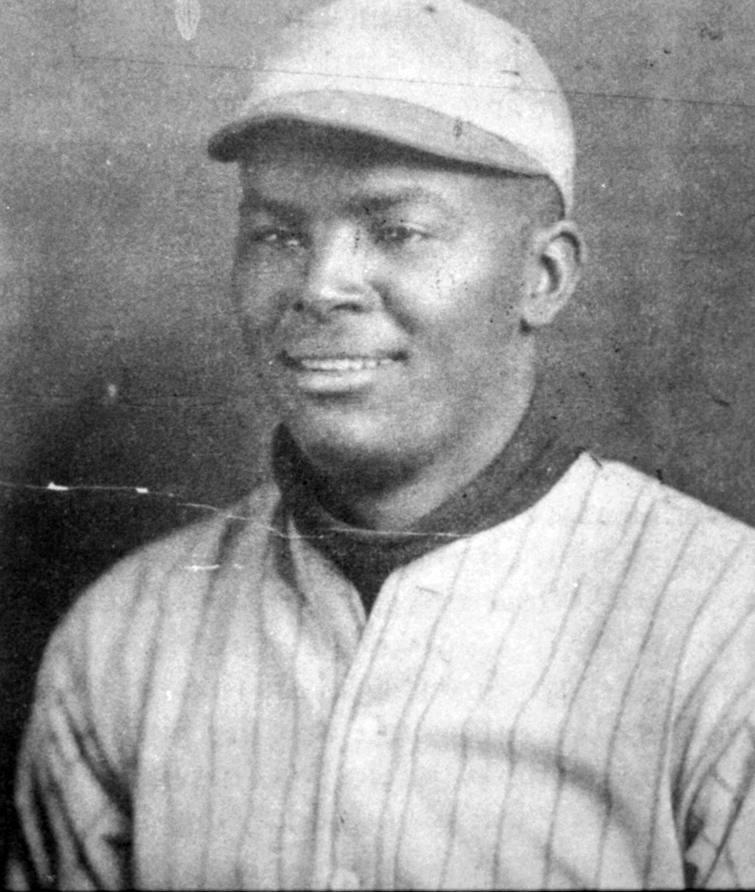

Biz Mackey

In the summer of 1946, Pittsburgh Courier columnist Wendell Smith gave Newark Eagles manager Biz Mackey all the credit for molding “together the best all-around pitching staff in Negro baseball.”1 Assembling talent is one thing, using it wisely and coping with obstacles that arise is a totally different talent. Mackey’s ace, Leon Day, opened the season with a no-hitter and led the team in wins. But he struggled with a sore arm and was of little use in the World Series. Mackey used his staff effectively, especially young Rufus Lewis, to capture a championship. His shortstop, Monte Irvin, simply said of Mackey, “As a player, as a manager, and as a personality, he was in a class by himself.”2

In the summer of 1946, Pittsburgh Courier columnist Wendell Smith gave Newark Eagles manager Biz Mackey all the credit for molding “together the best all-around pitching staff in Negro baseball.”1 Assembling talent is one thing, using it wisely and coping with obstacles that arise is a totally different talent. Mackey’s ace, Leon Day, opened the season with a no-hitter and led the team in wins. But he struggled with a sore arm and was of little use in the World Series. Mackey used his staff effectively, especially young Rufus Lewis, to capture a championship. His shortstop, Monte Irvin, simply said of Mackey, “As a player, as a manager, and as a personality, he was in a class by himself.”2

Capturing the Negro League banner in 1946 was the final jewel of Mackey’s brilliant career. Generally regarded as the finest defensive catcher in Negro League history, he was no slouch at the plate. The switch-hitter batted .411 in 1922 and .406 in 1930. He captured two World Series crowns in the Negro Leagues, one as a player and one as manager. He also won a championship in his only season in Cuba. In 2006 his life and talent were recognized with his selection to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

The journey to the top of his baseball world was not an easy one for Mackey. He was born the son of Texas sharecroppers. The absence of a birth certificate has led to speculation about his birthplace. In the past 30 years various researchers and writers have placed Mackey’s birth in Eagle Pass, Texas, as well as Seguin, Kingsbury, Luling, and Eagle Lake, all in Texas.3 Most current sources (Seamheads.com is a notable exception) accept the Eagle Pass location. Mackey listed his birthplace as Caldwell County (near Luling) on his World War I and World War II draft registrations.4

We do know that James Raleigh Mackey was one of six children born to John Dee (known as Dee to family and friends) and Beulah (Wright) Mackey, joining the family on July 27, 1897. His parents had wed in 1886 in Caldwell County and farmed there. In the 1900 census, Beulah listed herself as married but Dee was not living under the same roof. She was remarried in 1903 to Montgomery Meriwether, a farmer in a neighboring county. The 1910 census lists them in Guadalupe County between Seguin and Kingsbury. This blended family included Meriwether’s three daughters along with Beulah’s five surviving offspring.

The town of Luling, Texas, claims Mackey as its native son. He was wed there on October 20, 1917, to Ora Lee Dorn.5 It is uncertain if Mackey and Ora ever had children. Mackey did have a daughter named Narcissus. She was born in 1914 and later married George H. Odoms. They took up residence in Caldwell County and raised at least three children. Her oldest son, Riley Mackey Odoms, had a long and successful football career with the Denver Broncos.6

Biz and Ora Lee moved to Dallas, where he played baseball and worked as a laborer in 1918. They separated in 1919 and divorced a few years later. Ora Lee remarried in 1924. She and her husband, Will Elam, lived in California. Late in his life, Mackey reconnected with Ora Lee and she is listed on his death certificate as “Informant” and appears to have handled his funeral arrangements.7

Mackey received his schooling in nearby Prairie Lea, Texas, through the 10th grade. It was common in rural America for students to take an exam when their schooling ended. They would earn the equivalent of today’s high-school diploma with a good performance on the “Common Exam.” Mackey met the requirements when he completed the test.

The 1910 census noted that Mackey worked as a farm laborer when not in school. A few years later he took a job as a clerk in a railroad warehouse. At age 16 he reportedly joined his brothers Earnest and Ray playing on the Luling Oilers, the local semipro team. Mackey caught and pitched. Most sources claim he joined the San Antonio Black Aces in 1918. It is more likely that he played for the Dallas Black Giants that season.

Before Mackey earned his nickname, he was known to fans and writers as Riley, Rollie, or Raleigh. He appears in box scores sometimes as Mackey and sometimes by his first name.8 Based upon that information; it is likely that the Dallas catcher/pitcher in 1918 shown as Riley was in fact Mackey.9 He opened the 1919 season with the Giants but soon joined the Waco Black Navigators. His time with them was short-lived; he joined five other Waco players in jumping to the San Antonio Black Aces in early June.10

The addition of six starters to the Black Aces made them into a juggernaut. League standings showed them with a 45-10 record at the end of the Texas Colored League campaign in 1919. The Waco squad, which had started the season as the strongest team, disbanded shortly after the player defections. Dallas finished with a 51-17 mark and took on San Antonio in a postseason five-game championship.

After tight matches decided by a single run, the series came down to the nightcap of a doubleheader. The Aces sent Walter “Steel Arm” Davis to the mound, but he was pounded for three runs in the first. Mackey took the hill and allowed two more runs the rest of the way. In typical Hollywood fashion, Davis (who moved to center field) came to the plate in the eighth with two men on and lashed a double to give San Antonio a 7-5 victory and the title.

In December the leader of the Black Aces, L.W. Moore, announced his hopes of creating a Colorado-Texas-Oklahoma League. He also announced the signing of two catchers “who will fill the vacancy” created when Riley Mackey became a pitcher exclusively.11 The new league did not materialize, and the Black Aces remained in the Texas Colored League. Mackey took the hill as planned but when one of the catchers left the team, Mackey was returned to occasional catching duties. He highlighted his return with a 5-for-5 performance against the Black Giants on June 11.

A month later Mackey was enticed to leave Texas. On July 13 he and Aces teammate Henry Blackmon (mistakenly called Blackburn in the box score) debuted for the Negro National League Indianapolis ABC’s against the Cuban Stars. Mackey smacked a double in four trips in the 5-2 victory.12 Behind the plate he “worked in first-class style.” When the Cubans’ shortstop Matias Rios tried to steal second, “Mackey got the ball there so far ahead of him” that the second baseman walked up the line to tag Rios.13 Many authors have said Mackey’s contract was sold to the ABC’s, but an article in the San Antonio Evening News mentioned that Aces leadership was contemplating a lawsuit because the players had jumped their contracts.14

The ABC’s finished in fourth place. Mackey’s work at bat and behind the plate earned him a contract for 1921. He wintered in Texas and played ball there before returning to Indiana for spring training in early April. Indianapolis opened the season with two wins over the Cuban Stars but quickly fell off the pace after that. Mackey was even forced to take the mound and took three losses during the campaign. At the plate he hit .304, tied for the team lead in triples, and punched three home runs.

The ABC’s stayed together after the season and did some barnstorming. Mackey played third base late in the year and during the fall. Russell Powell handled the catching during the regular season. In the fall, Mack Eggleston was recruited to catch. The team also welcomed back Oscar Charleston, who had spent the season with St. Louis.

Charleston remained with the ABC’s in 1922 and the team finished second, tied with the Monarchs but trailing the Chicago American Giants. Charleston batted .395 and slammed 14 doubles, 9 triples, and 11 home runs. Not to be outdone, Mackey also mashed 14 doubles and hit a robust .411 while playing some shortstop and outfield along with catching.

In 1923 Ed Bolden, owner of the Hilldale Daisies (also called Giants and Darbys), led the formation of the Eastern Colored League (ECOL). A talent war ensued between the ECOL and the NNL that resulted in Mackey being signed by Hilldale. There he joined future Hall of Famers Judy Johnson, Pop Lloyd, and Louis Santop. Mackey was now 25 years old and had reached his full stature of 6 feet tall and probably 210 pounds.

The ECOL season opener was staged before 17,000 fans in Hilldale’s new park. Mackey caught and batted fifth in the lineup behind Lloyd. The game was called because of rain in the sixth with Hilldale up 4-2 over the Bacharach Giants.15 Mackey split the catching duties that season with Santop and spelled the 39-year-old Lloyd at shortstop. He is credited with leading the team in batting and RBIs. Hilldale posted a league-leading 32-17 record.

The nickname “Biz” first started to appear in 1923. Both the Philadelphia Inquirer and Pittsburgh Courier were using it by the end of the season. Mackey was a friendly, loquacious fellow with a competitive streak. He was known for giving the batter an earful when at the plate, hoping to break their concentration and focus. This “giving them the business” earned him the nickname of “Biz.” It should be noted that he was not the first “Biz” Mackey to make the sports pages. A featherweight boxer who twice had world-championship matches against Abe Attell – yes, that Attell of Black Sox infamy – had appeared in headlines for two decades as the catcher grew up.

Hilldale was the dominant ECOL team again in 1924, posting a 47-22 mark. Mackey led the team in batting and handled the pitching staff of Nip Winters, Red Ryan, and Phil Cockrell expertly. The two Black leagues staged a world series after the regular season and the Kansas City Monarchs captured five of the nine games.

After the season Mackey went to Cuba to play for Almendares. He joined Lloyd, Charleston, Wilbur “Bullet” Rogan, and Adolfo Luque on a team that proved to be a juggernaut. The season was ended early because of Almendares’ dominance. Mackey batted .309 with a team-leading 11 doubles.16

Because the regular season closed early, a postseason series was staged between an all-Cuban team and the “All Yankees” team made up of Negro League players. The All Yankees posted a 5-2-1 record. Mackey faced Cuban pitchers José Méndez and Martín Dihigo in the series and reportedly batted .333. Interestingly, Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis attended one of the games.17

Unlike many of his contemporaries who played winter ball in the Caribbean and Mexico, this was Mackey’s sole trip to the islands. He chose to spend his winters playing in the California Winter League, which featured a mix of Black and White teams. Mackey played 18 seasons on the West Coast and eventually made his permanent home in California. He is credited with a .366 batting average and 28 home runs in those seasons.18

The Hilldale squad ran away with the title again in 1925, posting a 52-15 record. The players did prove to be human during a week in June when they dropped three to the Harrisburg Giants and then lost a doubleheader to the Baltimore Black Sox. Mackey, who batted cleanup, produced only four hits in the games.19 Hilldale was knocked out of first place by the losses but regained the lead in mid-July and never looked back.

Hilldale earned a rematch with the Monarchs in an October series. Mackey struggled early in the series. He was 2-for-17 in the first four games and even dropped a ball in a home-plate collision. Baseball takes a team effort and his teammates picked him up as Hilldale captured three of the first four matches. In the final games, in Philadelphia, Mackey’s bat came alive and he had three hits, including a home run and double. Hilldale took five of six to capture the crown.20

Hilldale returned their core in 1926 and even added John Beckwith but its record dropped to 34-24 and the team finished in third place. In the offseason Mackey joined a barnstorming squad called the Philadelphia Royal Giants. They went to California and played in the winter league, posting a 26-11-1 record to win the crown. The team split up and some players returned to their teams for the regular season.

Mackey, along with Rap Dixon, Andy Cooper, and others, traveled to Japan and played a 48-game tour, the first tour by a Black entourage. The Americans entertained the locals with their brand of baseball, which included a pregame “shadow ball” routine. Years of experience in barnstorming had taught Mackey and his teammates the importance of keeping the local fans interested and entertained. Winning 20-0 would dampen enthusiasm and lessen the gate. It was to their advantage to keep the games close. In doing this they “played to the Japanese sense of honor and dignity.”21

Mackey established himself as a fan favorite. He launched a massive home run at the new Meiji Shrine Stadium in Tokyo. He fascinated and amazed the crowds with his ability to throw from the crouch. He was quick with a smile and genuine sincerity toward opponents and fans alike. After hitting him with a pitch, a Japanese hurler bowed to apologize, as is the style in the country. Mackey returned the gesture and bowed in return.22

Biz returned to Japan for a second tour five years later. On this tour he did some pitching and led the American contingent with a .388 batting average.23 The Japanese Baseball League would begin in 1936. Japanese baseball historian Kazuo Sayama credits the Royal Giants and Mackey with hastening the adoption of the game in his country. Babe Ruth’s visit in 1934 certainly created a countrywide sensation, but without the groundwork laid by the Negro Leaguers the game would not have reached its level of influence and popularity.

The lengthy tour in 1927 caused Mackey and his mates to miss the first half of the ECOL season. Hilldale was experiencing a poor first half. Joe Lewis handled the catching, but three players were suspended indefinitely in early June because of their indifferent play. Mackey was threatened with a five-year suspension after his return to the United States in early July. The suspension proved to be a hollow threat and he was in the lineup on July 28 for a 5-3 win over the Bacharach Giants.24

The Daisies finished third in the second half after being in fifth at the close of the first half. Mackey batted .284. He was recruited by Cum Posey in the fall and traveled with the Homestead Grays on their extensive barnstorming trip.

Hilldale added Oscar Charleston to the roster but dropped out of the league in March 1928. Playing an independent schedule against all comers, the team covered the East with appearances. Mackey found himself playing shortstop on numerous occasions. In late September he and second baseman Frank Warfield were added to the roster of the Baltimore Black Sox.

Hilldale moved into the American Negro League in 1929 and Mackey returned to the team. He stayed with it through 1931 after they went independent. In 1932 he declined a contract and stayed in California until promoter Lonnie Goodwin left for the Orient with his tour. The team played nine games in Honolulu, then crossed the Pacific to play in Japan. They also had 10 games scheduled in China and 30 in the Philippines.

From 1933 to 1935 Mackey played with the Philadelphia Stars. He was selected by fan vote as the starting catcher in the inaugural East-West All-Star Game, played before 19,000 fans in Comiskey Park in Chicago. He split time with Josh Gibson at catcher in the 11-7 loss by his East team. In 1936 he was traded to the Columbus Elite Giants, but that franchise moved to Washington. Mackey had his first taste as manager when he filled in for Candy Jim Taylor. He also earned a starting spot in the All-Star Game.

The consensus among fans and scholars of the Negro Leagues was that Gibson was the better hitter, but Mackey was by far his defensive superior. Author James Riley said it best: “Considered the master of defense, (Mackey) possessed all the tools necessary behind the plate. … An expert handler of pitchers, he studied people. … [H]e was a master at … framing and funneling pitches. Pitchers recognized his generalship and liked to pitch” to Mackey. His surprising agility for a big man enabled him to play the infield.25

In 1937 Mackey took over as Washington manager when Taylor moved on. Mackey was selected by the fans as the manager for the East-West All Star Game. His East squad emerged with a 7-2 victory. He was tipped off about the talent of a teenager named Roy Campanella. Washington signed Campanella for $60 a month and Mackey began the task of turning him into a professional catcher. When Mackey left the Elite Giants, Campanella was ready to step into his shoes. Campanella recalled, “Biz Mackey was the master of defense of all catchers.” Campanella always was quick to give Mackey credit for his development.26

Mackey was sold to the Newark Eagles in 1939. He took over as manager from Dick Lundy partway through the 1940 season. Despite a growing waistline and aching knees, Mackey continued to be an asset on the field. In 1942 he had a falling-out with the owners, Abe and Effa Manley, over salary and was replaced by Willie Wells.

Mackey returned to his California home. He supported the war effort by working at North American Aviation in Los Angeles and played baseball with the San Francisco Sea Lions. When the Manleys had a dispute with Wells, Mackey returned to Newark in 1945. He continued to play occasionally, mostly at first base.

The Eagles captured the first-half championship in 1946 with a record of 25-9. They weathered some hard times in the second half, including the demise of the team bus which forced players to drive their own cars to games at one point.

Mackey was renowned for his levelheadedness and emotional control on the field throughout his managerial career. He uncharacteristically lost his cool in a game against the Cleveland Buckeyes in late July of 1946 and pulled the Eagles from the field in protest. The Black press took him to task for being unsportsmanlike. Effa Manley came to his defense with a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier and the issue blew over.

The Eagles took the second half with a 22-7 mark and met the Kansas City Monarchs in the World Series. Led by Monte Irvin’s bat and the pitching of Rufus Lewis, Newark captured the pennant, a triumph that earned each player a diamond ring.

Mackey managed the Eagles again in 1947. The Eagles sold Larry Doby to the Cleveland Indians that year. Mackey recommended moving the youngster from second base to the outfield, which the Indians did. Mackey was named manager of the East squad for the All-Star Game. The game was played on his 50th birthday and Mackey rewarded himself by pinch-hitting in the eighth inning. He had seen very little action that season, and his waistline had grown to where writer Wendell Smith called him paunchy. His girth did not affect his batting eye; he walked. He immediately replaced himself with Vic Harris.

Mackey retired to California, where he continued to play with the Sea Lions and other teams. Fate has an odd way of impacting our lives. When Mackey made his first trip to Japan, he was intrigued to find a large contingent of Afro-Asians living in Tokyo. He met a young woman of mixed ancestry named Lucille and they became friendly. On later trips to Japan he made it a point to contact her. The pair understandably lost contact during the war.

According to Mackey’s great-nephew Ray, Lucille and her family came to the United States in the late 1940s or early 1950s. She and Mackey were reunited in San Francisco. They spent the rest of their lives together. Mackey’s reputation in baseball was that of a jovial, trash-talker but in his private life he was very reserved. He bordered on reclusive and did very little to publicize his baseball life.

That changed, for one day at least, on the evening of May 7, 1959. A reported 93,000 fans attended an exhibition game in the Los Angeles Coliseum between the Dodgers and the Yankees. The occasion was to pay tribute to Roy Campanella, the longtime Dodgers catcher, who had been paralyzed in a traffic accident the previous year. In the crowd were Mackey and his nephew Ray. In his thank-you speech to the throng, Campy called for Mackey to join him on the field and made sure that everyone there realized how important Biz had been in his development.27

After the Campanella tribute, Mackey lived quietly in Los Angeles and worked as a forklift driver for the Stauffer Chemical Company. In those days before the publication of Only the Ball Was White,28 it was commonplace for a former Negro League player to live in anonymity. Lucille, called “Aunt Lucy” by the family, died a few months before Biz. The family wondered if the loss of the love of his life hastened Mackey’s demise. Biz died on September 22, 1965, in Los Angeles. He was buried in that city’s Evergreen Cemetery. His death received no coverage in The Sporting News nor did it appear in the Necrology of the 1966 Sporting News Official Baseball Guide. In the 1970s and beyond, Mackey’s name would make newspapers as a Negro League player who deserved Hall of Fame consideration. His time to enter Cooperstown finally came in 2006.

Sources

Statistics come from Baseball-Reference.com unless otherwise noted. Standings of teams come from The Negro League Book published by SABR in 1994. A big thank-you to Ray Mackey III for his tremendous wealth of information about Biz and the Mackey family. I would also like to extend my gratitude to renowned Negro League historian Larry Lester for his support and guidance in this research. Finally, a tip of the hat to the Allen County Library in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where a researcher named Cristella searched the Los Angeles Sentinel for Mackey info.

Notes

1 Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 13, 1946: 16.

2 templepress.wordpress.com/2018/01/24/biz-mackey-a-giant-behind-the-plate/.

3 John Holway listed the birthplace as Seguin in his 1988 book Blackball Stars; other sources found in Mackey’s Hall of Fame file suggest Kingsbury, which is east of Seguin and Luling; in a correspondence from 2000 there was mention of Eagle Lake.

4 ancestry.com/interactive/6482/005152930_01688?pid=16453080&backurl=https://search. Last accessed February 26, 2019. search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=YMDraftCardsWWII&indiv=try&h=17975243. Last accessed March 11, 2019.

5 search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?dbid=60183&h=66427&indiv=try&o_vc=Record:OtherRecord&rhSource=8842.

6 Brad Gray, “Biz’s Big Day,” Austin American-Statesman, July 31, 2006: 20.

7 Gary Krause, email exchange from February 2000 found in Mackey’s Hall of Fame file. Krause was researching Mackey’s personal information and corresponding with a Hall of Fame library researcher, Eric Enders.

8 An example would be the box scores in the Dallas Express from August 23, 1919: 11, in which he was listed as Riley in the first game and Releigh (sic) in game two.

9 “Dallas Black Giants Win,” Dallas Morning News, August 12, 1918: 7. He was also residing in Dallas in August when he signed up for the draft. See Note 4.

10 Gary Ashwill, “Steel Arm Davis,” Agate Type, November 3, 2014. agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2014/11/steel-arm-davis.html. Last accessed February 26, 2019.

11 San Antonio Evening News, December 13, 1919: 10.

12 “New Players Show Class,” Indianapolis Star, July 14, 1920: 10.

13 “New Players Show Class.”

14 “Suit May be Filed for Taking Players from Black Aces,” San Antonio Evening News, August 2, 1920: 7.

15 “Hilldale Opens New Park with Victory,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 29, 1923: 20.

16 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 157-59.

17 Figueredo, 162.

18 Geri Strecker, “Winter Baseball in California: Separate Opportunities, Equal Talent,” The National Pastime (SABR, 2011), accessed on February 28, 2019 at sabr.org/research/winter-baseball-california-separate-opportunities-equal-talent.

19 “Harrisburg Sweeps Three-Game Series with Hilldale; Leads Eastern League,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 27, 1925: 12.

20 Game coverage from the Pittsburgh Courier of October 10 and 17.

21 Gary Joseph Cieradkowski, “Biz Mackey: International Man of Clout,” Infinite Card Set blog October 2013. Last accessed on February 28, 2019 at infinitecardset.blogspot.com/2013/10/160-biz-mackey-international-man-of.html.

22 Kazuo Sayama and Bill Staples Jr., Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (Fresno, California: NBRP Press, 2019), 121.

23 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay for Play Outside the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 108.

24 “Mackey’s ‘Five-Years Suspension’ Over, Aids Hilldale in Win Over Seasiders,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 30, 1927: 16.

25 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 502-03.

26 Gray, “Biz’s Big Day.”

27 Telephone interviews with Ray Mackey III, March 6 and 11, 2019.

28 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Full Name

James Raleigh Mackey

Born

July 27, 1897 at Eagle Pass, TX (US)

Died

September 22, 1985 at Los Angeles, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.