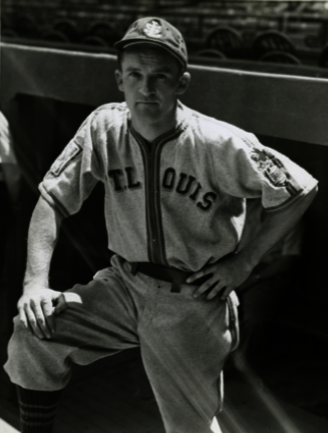

George McQuinn

It was a long journey for George McQuinn to the 1947 New York Yankees, where he became a key figure in their run to the pennant. In addition to his normal stellar play at first base, McQuinn batted .304 and drove in 80 runs, a significant upgrade from Nick Etten, a .232 hitter for the third-place Yankees in 1946. In late May McQuinn was batting a league-leading .392, and by the All-Star break he was still among the league leaders at .328. For his efforts, the fans chose McQuinn as the American League’s starting first baseman in the All-Star Game. One sportswriter described his success as “the story book story behind the Yankees’ surprising success … in 1947.”1

It was a long journey for George McQuinn to the 1947 New York Yankees, where he became a key figure in their run to the pennant. In addition to his normal stellar play at first base, McQuinn batted .304 and drove in 80 runs, a significant upgrade from Nick Etten, a .232 hitter for the third-place Yankees in 1946. In late May McQuinn was batting a league-leading .392, and by the All-Star break he was still among the league leaders at .328. For his efforts, the fans chose McQuinn as the American League’s starting first baseman in the All-Star Game. One sportswriter described his success as “the story book story behind the Yankees’ surprising success … in 1947.”1

McQuinn’s contribution was perhaps equal parts unexpected and gratifying. It was unexpected because he had hit only .225 in 1946 for the cellar-dwelling Philadelphia Athletics, who released him after the season. It looked as though at the age of 36, without a job and with a bad back, his major-league career might be at an end. One article even referred to McQuinn as “the man nobody wanted.”2 New Yankees manager Bucky Harris, however, was an old fan of McQuinn’s and the New Yorkers had a need at first base, so on January 25, 1947, the Yankees signed him as a free agent, setting the stage for his surprising landmark season.3

George Hartley McQuinn was born on May 29, 1910, in Arlington, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, DC. His parents were William McQuinn, an electrician, and Ada (Hartley) McQuinn, who was born in England but emigrated in 1899. The pair had seven children – five boys and two girls. George, the third son, began playing baseball at the age of 7. When he was 12 he bought a George Sisler model first baseman’s glove, but McQuinn patterned himself after Joe Judge, the slick-fielding first baseman of the hometown Washington Senators.4

McQuinn starred in basketball and baseball at Washington-Lee High School. He was a left-handed pitcher as well as batter, but his high-school coach began playing him at first base full-time. McQuinn had an offer to play baseball at the College of William and Mary but decided instead to try for a career in professional baseball.

In 1930 he was working as an elevator operator for the Chamber of Commerce in Washington and playing for a semipro team in Northern Virginia. After a tryout arranged by his semipro manager, the New Haven (Connecticut) Profs of the Class A Eastern League signed McQuinn to his first professional contract. Playing time was limited, however, and the league was a fast one for a 19-year-old. McQuinn could manage only two hits in 19 at-bats and in May New Haven released him.

Fortunately for McQuinn, he had made an impression on Joe Benes, one of the veteran infielders for the Profs. Benes recommended him to Yankees scout Gene McCann, who signed McQuinn to a contract with the Wheeling (West Virginia) Stogies, the Yankees’ farm club in the Class C Middle Atlantic League.5 McQuinn’s .288 batting average for the Stogies earned him a promotion for 1931 to the Scranton Miners of the Class B New York-Penn League, where he hit a strong .316 and drove in 101 runs while hitting just five home runs.

In 1932 McQuinn batted a combined .334 with 100 RBIs while splitting the season between the Albany (New York) Senators of the Eastern League and, after the league folded on July 17, the Binghamton (New York) Triplets of the New York-Penn League. That performance earned him a spring-training invitation in 1933 with the International League Newark Bears, the Yankees’ top farm club. The Bears, however, had the veteran Johnny Neun at first base so they shipped McQuinn to the rival Toronto Maple Leafs. Despite an excellent start with the Leafs, he was sent back to Binghamton, where he batted a league-leading .357, drove in 102 runs, and won the league’s Most Valuable Player award.

McQuinn played a full season with Toronto in 1934, hitting .331 in 138 games, before fracturing an ankle sliding into third base in the Junior World Series. By now some writers were wondering if the Yankees would consider trading Lou Gehrig to make room for McQuinn at first base.6

Yankees farm director George Weiss sent the Patient Scot, as the press sometimes called McQuinn, to Newark in 1935, where he hit .288 in 563 at-bats, subpar for him because of a sore shoulder. Defensively, he broke a 22-year-old International League record for first basemen by fielding .997 for the year.

McQuinn had yet to be invited to a Yankees’ spring training, but he continued to attract attention from other organizations. Before the 1936 season, the Cincinnati Reds, looking to replace Jim Bottomley at first base, purchased McQuinn conditionally, meaning they could return him to the Yankees up until June 1. McQuinn, still just 25 years old, finally got his big-league chance and it was a flop. The Reds, under manager Charlie Dressen, immediately tried to get him to pull the ball rather than hit to all fields as was his custom. He was unable to adjust, and in 134 at-bats hit only .201 with no home runs, prompting the Reds to send him back to the Yankees on June 1.

McQuinn returned to Toronto and hit a reaffirming .329 in 410 at-bats. While there, he met Kathleen Baxter, originally from Belfast, Northern Ireland, on a blind date at the ballpark. They married after the 1937 season and eventually had two daughters, Virginia and Victoria.

Kathleen knew little about baseball. The first time she saw a game in which it rained, she was perplexed about why the team had removed the tarpaulin when the rain stopped. After the game, she asked George to explain why he had to play on a muddy field when it would have been so much cleaner to play on the canvas.7

With Lou Gehrig still going strong for the Yankees, McQuinn found himself back with Newark in 1937. Playing for what is widely regarded as the best minor-league team ever, he batted .330 and stroked 21 home runs, as the Bears won the pennant by 25½ games, finishing with a 109-43 record.8 McQuinn later recalled that his friends used to kid him, saying, “Doesn’t Gehrig ever have the mumps, whooping cough or measles? Why don’t you send him a letter telling him he better take a vacation or else?”9

Under the rules then in place, McQuinn became eligible to be drafted by another major-league team after the 1937 season when the Yankees failed to place him on their big-league roster. As a result, the St. Louis Browns selected McQuinn with the first pick in the Rule 5 draft and installed him at first base to begin the 1938 season.

McQuinn soon discovered that the Yankees had made the Browns pay more than the $7,500 draft price for him, in violation of the draft rules. McQuinn wrote Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis a letter of complaint and then showed up at his office in Chicago. Landis told McQuinn to go ahead and report to the Browns but promised to investigate and get back to him. But McQuinn never did hear back from the Commissioner, which rankled him for many years.10

McQuinn made sure he did not flub his second chance at the big leagues. On Opening Day he clubbed a single, double, and triple against one of the best pitchers in the league, Cleveland’s Johnny Allen. Typically, a slow starter, he hovered around the .270 mark for the first two months of the season, before improving to .300. Then, on July 24, he had four hits in four at-bats against the Washington Senators, beginning a torrid 34-game hitting streak during which he batted .386 (56-for-145). For the season he was runner-up to Mel Almada on the seventh-place Browns with a .324 batting average, while slugging 12 home runs and driving in 82 runs, second in both categories to Harlond Clift.

Manager Gabby Street had scouted McQuinn at Newark and quickly lauded him as the best defensive first baseman in the league since George Sisler, and better than Jim Bottomley or Ripper Collins of the Cardinals.11

The 1939 season brought more of the same as McQuinn led the Browns with a .316 average while playing in all 154 games. He improved his home run and runs batted in totals to 20 and 94 respectively for the last-place Browns. For his efforts, McQuinn was named to his first All-Star team, although he did not appear in the game.

After the season the Yankees sought to trade for McQuinn, who had been blocked in the minor leagues by Gehrig for all those years, to replace the ill Gehrig at first base. Yankees general manager Ed Barrow reportedly offered the Browns $75,000 plus Babe Dahlgren and other players for McQuinn. The American League, however, had instituted a bizarre rule barring trades with the pennant winner, which ended up quashing the deal.12 Yankees general manager Ed Barrow later lamented that the failure to land McQuinn had cost the Yankees their fifth straight pennant in 1940.13

Thus, McQuinn found himself back with St. Louis in 1940. He slipped to a .279 average for the improved sixth-place Browns, but made his second All-Star team, although he again did not appear in the game. McQuinn, who was particularly adept at turning the 3-6-3 double play,14 also led American League first basemen in fielding average.

Although only 5-feet-11, McQuinn quickly became known as the best fielding first baseman in the league and was often compared to George Sisler, Joe Kuhel, and Hal Chase. Veteran catcher Frank Mancuso called him the best first baseman he had ever seen.15 As a result, the Rawlings Sporting Goods Company marketed a George McQuinn model first baseman’s glove. Years later, it was reported that President George H.W. Bush, another slick-fielding first baseman from his days at Yale, kept his old first baseman’s “claw” glove in his desk drawer in the Oval Office at the White House. It was a George McQuinn model.16

McQuinn improved his batting average to .297 in 1941, with 18 homers and 80 runs batted in. The highlight of his season came on July 19, when he hit for the cycle. For the second consecutive year, McQuinn led American League first basemen in fielding percentage. After the season he was to be included in what would have been a blockbuster trade with the National League champion Brooklyn Dodgers. The deal would have sent McQuinn and third baseman Harlond Clift to the Dodgers for reigning National League MVP Dolph Camilli, Cookie Lavagetto, and cash. McQuinn and Clift, however, could not clear American League waivers so the deal did not happen.

A back ailment that was becoming chronic hampered McQuinn in 1942 and 1943; his batting average slipped to .262 in ’42 and .243 in ’43. It had gotten to the point that he needed to wear a brace in order to play. With World War II in full swing, McQuinn was ordered to take an Army pre-induction physical in June of 1943, but was rejected because of his back.17

The Browns were a veteran team and would lead the league in 4-Fs, medical discharges, and family-related deferments. While other teams were losing key players to the service, the Browns were relatively unaffected. They opened the 1944 season with 18 4-Fs and 13 were with the team for the long haul.18 As a result, the 1944 Browns, playing in a weakened American League, won their first American League title in a thrilling pennant race that went down to the last day of the season. The Browns entered that day tied for first place with the Detroit Tigers, who were playing the Washington Senators in Detroit. The Browns were hosting the New York Yankees and learned in the fourth inning that the Tigers had lost. Although the Yankees got off to a 2-0 lead, the Browns came back to win 5-2 behind the stellar pitching of Sig Jakucki. With a runner on second and two out in the ninth the Yankees’ third baseman Oscar Grimes hit a towering foul ball about ten feet outside of first base. McQuinn squeezed the ball for the final out and was immediately mobbed by fans and players spilling onto the field.

McQuinn held on to the ball that ended the game as if it were made of gold. In the clubhouse winning pitcher Jakucki approached McQuinn and said, “Look pal, that ball means a lot to me. How about giving it to me?”

McQuinn replied, “Well, let’s be neighborly about this thing. I’ll give you half of it.” Browns’ owner Don Barnes overheard the exchange and asked for a saw. Jakucki and McQuinn then spent ten minutes trying to saw the ball in two but failed to make any headway. Finally, batboy Bobby Scanlon flipped a coin to decide the winner. McQuinn won the flip and got the now thoroughly chewed up baseball.19

The 34-year-old McQuinn hit only .250 for the season but his 11 home runs were second on the team and he again led the league’s first basemen in fielding average. He also made his fourth All-Star team, this time as the starting first baseman. He played the entire game, singling in the first inning off Bucky Walters to go 1-for-4, as the Americans went down to defeat, 7-1.

The Browns faced the St. Louis Cardinals, who had breezed to the National League pennant, in the only “All-St. Louis” World Series. In the fourth inning of the first game, with a man on, McQuinn blasted a towering drive off Mort Cooper onto the right-field roof to lead the Browns to a 2–1 victory. Then, in Game Two, McQuinn was involved in a play that is often considered the turning point in the entire Series. With the score tied 2-2, he led off the top of the 11th with a double off the screen in right field. Mark Christman attempted to sacrifice McQuinn to third by pushing a bunt toward third base, but Cardinals’ pitcher Blix Donnelly pounced off the mound and threw to Whitey Kurowski at third. Kurowski made a great stab of the ball and tagged McQuinn out by an eyelash. Observers were surprised that Donnelly had even elected to throw to third. Gene Moore, the next batter, lofted a long outfield fly that would have easily scored McQuinn but was instead just the second out of the inning. The Cardinals quickly scored the winning run in the bottom of the inning to tie the series at one apiece.20

The Browns won Game Three 6-2 and might well have been up three games to zero but for Donnelly’s play at third in Game Two. But they hit only .183 and lost Games Four, Five, and Six to lose the Series four games to two. McQuinn was the one bright spot, batting .438 with seven hits, seven walks, and five of the team’s nine runs batted in. His home run in Game One was the only one the Browns hit.

McQuinn was again called for a pre-induction physical in early 1945 but was rejected under a new edict that ballplayers not fit for combat should not be drafted. McQuinn improved his batting average to .277 in 483 at-bats as the Browns finished a respectable third, six games behind the pennant-winning Detroit Tigers.

Shortly after the season, the Browns swapped McQuinn to the Philadelphia A’s for first baseman Dick Siebert. The deal hit a snag when Siebert could not agree to terms with the Browns and retired from baseball, but Commissioner Happy Chandler ruled that the A’s could keep McQuinn nonetheless.21 The last-place A’s may have regretted the commissioner’s decision as McQuinn had his worst year in baseball in 1946, hitting only .225, with three home runs and just 35 RBIs. He struggled through some long slumps and incurred the ire of the Athletics fans. At one point, after striking out four times and popping up three times in a doubleheader, McQuinn decided to quit the game, but Kathleen talked him out of it, telling him he’d had too many good seasons not to be able to endure a bad one.22

The Athletics gave McQuinn his unconditional release on January 9, 1947. Connie Mack, the venerable manager of the Athletics, was heard to remark that McQuinn had “played baseball one year too long.”23

That set the stage for McQuinn to sign with the Yankees, 17 years after he first became a Yankee farmhand.24 McQuinn did not accompany the team on its spring tour through Latin America in 1947, joining them when they returned to St. Petersburg, Florida. By that time the Yankees’ lineup looked set, with Tommy Henrich at first base and Yogi Berra in right field. Charley Keller, however, pulled a muscle in early April, sending Henrich temporarily to left field and giving McQuinn an opening at first base. He began hitting well immediately, even against left-handers, and soon took over the first-base position, with Henrich occupying right field and Berra the catcher’s spot.25

Early in the season McQuinn asked traveling secretary Arthur Patterson if he could room alone on the road. His chronic back pain made it hard for him to sleep at night, and he worried that his tossing and turning would disturb his roommate. He also found that being able to sprawl out in a double bed helped him sleep better.26

With his back responding, the 37-year-old McQuinn got off to a great start and by early June was leading the league with a .354 average. Only a few months after being released by the worst team in baseball, McQuinn was named as a starter for the American League All-Star team. He played the entire game at first base, going hitless in four at-bats.

Throughout his career, McQuinn had a reputation for having a dry sense of humor but being quiet and not very talkative. His Browns teammate Don Gutteridge recalled that McQuinn would say hello when he arrived for spring training and goodbye when he left in the fall.27 Bobby Brown remembered that his nickname on the Yankees was Si, short for silent. Brown recalled McQuinn as a great teammate and a very nice man.28 His typical postgame ritual on the road was to smoke an after-dinner cigar in the hotel lobby while watching the people go by, and then head to bed at 10 o’clock.29

McQuinn tailed off late in the year to a final .304 average – second highest on the team – with 13 home runs and 80 RBIs. Unlike 1944, however, he struggled in the World Series, hitting only .130 in 23 at-bats as the Yankees defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers in seven games.

Although he would turn 38 in May 1948, the Yankees wanted McQuinn back, and after a brief holdout, he signed for the ’48 season. He got off to another exceptional start, with an average of .340 on May 31, and was again named the All-Star Game starter at first base for the American League, his sixth All-Star team. He played the entire game and was one of three players, along with Richie Ashburn and Stan Musial, with two hits as the American League won, 5–2. He also set an All-Star Game record with 14 putouts and tied a mark with 14 total chances. But he wore down over the long season and ended the campaign hitting .248 in 94 games as the Yankees finished third in a tight, three-team pennant race.

The Yankees released McQuinn after the season, and he retired to Arlington, Virginia, to run a sporting-goods store bearing his name. He was lured back to baseball in 1950 by the Boston Braves organization with an offer to manage the Quebec Braves in the Class C Canadian-American League. The team finished first with a 97-40 record, won the semifinals four games to one, and swept the finals in four games against the Amsterdam (New York) Rugmakers. Along the way, McQuinn put himself into 74 games and hit .318 in 242 at-bats.

The Braves switched to the Provincial League, also Class C, in 1951 as McQuinn again managed the team, this time to a fourth-place finish. Although he was now 41 years old, he was still a playing manager, hitting .301 in 136 at-bats. McQuinn was back managing Quebec in 1952 and guided the Braves to a second-place finish, while appearing as a pinch-hitter 12 times, the final at-bats of his playing career.

McQuinn continued to manage Quebec through the 1954 season with remarkable success. In his five years leading the Braves, the club finished first twice, second once, third once, and fourth once, and won the league playoffs four times.

The Braves organization promoted McQuinn to manage the Atlanta Crackers in the Double-A Southern Association for 1955. With the club’s record at 49-49 on July 16, McQuinn stepped down as manager. However, his magic touch returned in 1956. On July 1 of that year he took over the managerial reins of the Boise Braves in the Class C Pioneer League and led them to the pennant. McQuinn returned to Boise for 1957 but the team finished seventh. In 1958 he moved up to manage the Topeka Hawks in the Class A Western League, where the team also finished seventh in an eight-team circuit.

Now 48, McQuinn wanted to spend his summers closer to his Arlington home so he became a scout for the Washington Senators, concentrating on Virginia and West Virginia. He later scouted for the Montreal Expos before retiring from baseball in 1971 after 42 years in the game. He published a detailed guide to playing baseball in 1972 and delighted in giving it to any youngster who expressed an interest.

In an interview late in life, McQuinn lamented that Lou Gehrig probably cost him four years of his big-league career. He expressed some bitterness that the Yankees had never taken him to spring training, despite his outstanding years in the minor leagues.30 McQuinn also had little use for Commissioner Landis, who refused to do anything when the Yankees violated baseball rules in sending him to the Browns in 1937.

But with the exception of his appeal to Landis, McQuinn was never one to make waves. During his minor-league career, his name was twice butchered by the teams he was playing for. In Scranton, the public-address announcer called him Mike McQuinn and later in Newark, an error led him to be listed on the roster as Jack. He never corrected either mistake and for the rest of his life was known as Mike to those who had known him in Scranton and Jack to those from Newark.31

McQuinn’s major-league career spanned 12 years and four teams. He ended with a lifetime batting average of .276 with 1,588 hits in 1,550 big-league games. Although it was not as uncommon then as it is now, he walked more times (712) than he struck out (634). He is most remembered as a stalwart of some mediocre St. Louis Browns clubs in the late 1930s and early 1940s and as the star of the 1944 World Series. But he had a major impact on the ’47 Yankees’ run to the pennant after Yankees manager Bucky Harris plucked him off the scrap heap.

McQuinn died on December 24, 1978, in Alexandria, Virginia, of complications from a stroke. He was 68 years old.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin. It originally appeared in “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by Lyle Spatz.

Sources

Borst, Bill, The Best of Seasons: The 1944 St. Louis Cardinals and St. Louis Browns (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1995).

Borst, Bill, Still Last in the American League (West Bloomfield, Michigan: Altwerger & Mandel Publishing Co., 1992).

Cleve, Craig Allen, Hardball on the Home Front, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2004).

Cobbledick, Gordon, “McQuinn Bolsters Three Positions,” Baseball Digest, September, 1947.

Dahlgren, Matt, Rumor in Town (Ashland, Ohio: Woodlyn Lane, 2007).

Finoli, David, For the Good of the Country – World War II Baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2002).

Goldstein, Richard, Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1980).

Golenbock, Peter, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 2000).

Gross, Milton, “The Man Nobody Wanted,” in Yankee Doodles (Boston: House of Kent Publishing Co., 1948).

Gutteridge, Don, as told to Ronnie Joyner and Bill Bozman, Don Gutteridge in Words and Pictures (Dunkirk, Maryland: Pepperpot Productions, Inc., 2002).

Gutteridge, Don, with Ronnie Joyner and Bill Bozman, From the Gas House Gang to the Go-Go Sox – My 50-Plus Years in Big League Baseball (Dunkirk, Maryland: Pepperpot Productions, Inc., 2007).

Heidenry, John, and Brett Topel, The Boys Who Were Left Behind (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2006).

Heller, David Allan, As Good As It Got: The 1944 St. Louis Browns (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2003).

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Second Edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997).

Karst, Gene, and Martin Jones, eds., Who’s Who in Professional Baseball (New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House, 1973).

Levitt, Daniel R., Ed Barrow – The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2008).

Linthurst, Randolph, Newark Bears (Trenton: White Eagle Printing Co., Inc., 1978).

Mayer, Ronald A., The Newark Bears: A Baseball Legend (East Hanover, New Jersey: Vintage Press, 1980).

Mead, William B., Even the Browns: The Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties (Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc., 1978).

Porter, David L., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball, Revised and Expanded Edition G-P (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000).

Shatzkin, Mike, ed., The Ballplayers (New York: Arbor House, 1990).

Van Lindt, Carson, One Championship Season: The Story of the 1944 St. Louis Browns (New York: Marabou Publishing, 1994).

Vincent, David; Lyle Spatz, and David Smith, The Midsummer Classic:The Complete History of the All-Star Game (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

Telephone interview by author with Dr. Bobby Brown, June 23, 2011.

Notes

1 Milton Gross, “The Man Nobody Wanted,” in Yankee Doodles, 98.

2 Gross, 97.

3 Cy Kritzer, “Bucky Played Hunch in Signing of McQuinn,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1947, 6; Frances E. Stann, “McQuinn Feels Right at Home as Yank,” The Sporting News, undated, from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

4 Undated and unidentified clipping from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

5 Frederick G. Lieb, “ ‘Forgotten Yankee’ McQuinn Proves Star at 37,” The Sporting News, undated, from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

6 Michael F. Gaven, “George McQuinn, Kept Off Yankees for Eight Seasons by Gehrig, Getting His Chance With Browns Via Draft,” The Sporting News, February 28, 1938.

7 Gross, 103.

8 Of the players who spent all or the bulk of the season with Newark, everyone but Jack Fallon had substantial major league careers. In addition to McQuinn, they included Joe Gordon, Charlie Keller, Babe Dalhgren, Atley Donald, Joe Beggs, Mario Russo, Buddy Rosar, Willard Hershberger, Bob Seeds, Spud Chandler, Jim Gleeson, Johnny Niggeling, Vito Tamulis, and Steve Sundra among others. Ronald A. Mayer, The 1937 Newark Bears, ix-xviv.

9 Henry P. Edwards, January 29, 1939, American League Press Release in the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

10 St. Louis Browns general manager Bill DeWitt later admitted that the Yankees had made the Browns sell them first-baseman Harry Davis for $2,500 in order to obtain McQuinn. William B. Mead, Even the Browns: The Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties, 61-62.

11 The Old Scout, “Rookie McQuinn Ties Hornsby’s Batting Streak,” unidentified article dated August 25, 1938 in the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

12 Daniel R. Levitt, Ed Barrow – the Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty, 333; Frederick G. Lieb, “ ‘Forgotten Yankee’ McQuinn Proves Star at 37,” The Sporting News, undated, from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

13 Joe King, “Flag No Surprise to McQuinn – He Knew It Back in January,” unidentified article dated September 16, 1947 from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

14 “McQuinn Sets Pace Again,” unidentified clipping dated January 15, 1942 from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library; Henry P. Edwards, January 29, 1939, American League Press Release in the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

15 Craig Allen Cleve, Hardball on the Home Front, 15.

16 “. . . It’s a George McQuinn ‘Claw,’” unidentified article dated October 19, 1989 from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

17 Richard Goldstein, Spartan Seasons, 207; “Army Rejects Stephens and McQuinn of Browns,” unidentified article dated June 29, 1943 from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library..

18 John Heidenry and Brett Topel, The Boys Who Were Left Behind, 44.

19 John Heidenry and Brett Topel, 12-15.

20 Don Gutteridge with Ronnie Joyner and Bill Bozman, From the Gas House Gang to the Go-Go Sox, 164, 166; Heidenry and Topel, 95-96..

21 “McQuinn Stays With Athletics,” unidentified article dated April 19, 1946 from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

22 Gross, 102.

23 Gross, 98.

24 Rud Rennie, “McQuinn Hopes 17-Year Desire To Become Yankee Is Realized,” unidentified article dated March 5, 1947 in the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library; Dan Daniel, “Merry-Go-ropund Brings Brass Ring for McQuinn,” The Sporting News, April 23, 1947..

25 Dan Daniel, “McQuinn Named Yank 1st Sacker,” unidentified article dated April 12, 1947 from the George McQuinn clippings file, National Baseball Library.

26 Gross, 101-102.

27 Don Gutteridge as told to Ronnie Joyner and Bill Bozman, Don Gutteridge in Words and Pictures, 73; Don Gutteridge with Ronnie Joyner and Bill Bozman, From the Gas House Gang to the Go–Go Sox,.173.

28 Author interview with Dr. Bobby Brown, June 23, 2011.

29 Gross, 106-107.

30 William B. Mead, , 41.

31 Gross, 106.

Full Name

George Hartley McQuinn

Born

May 29, 1910 at Arlington, VA (USA)

Died

December 24, 1978 at Alexandria, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.