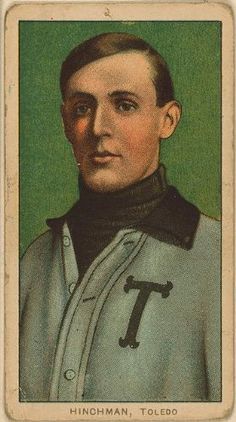

Harry Hinchman

Brothers Harry and William Hinchman were Philadelphia natives who devoted their lives to baseball. Harry was the elder (born August 4, 1878) and played professionally for 19 seasons. He added 12 more seasons as a minor-league manager before he died at age 54. He made a lasting impression in every city (there were 14 of them) during his long baseball tenure. An unidentified writer for the St. Paul Pioneer Press noted, “Quiet, easy-going, unpretentious Harry Hinchman is one of the most popular players. … [F]ew men possess greater baseball sense than Hinchman does.”1

Brothers Harry and William Hinchman were Philadelphia natives who devoted their lives to baseball. Harry was the elder (born August 4, 1878) and played professionally for 19 seasons. He added 12 more seasons as a minor-league manager before he died at age 54. He made a lasting impression in every city (there were 14 of them) during his long baseball tenure. An unidentified writer for the St. Paul Pioneer Press noted, “Quiet, easy-going, unpretentious Harry Hinchman is one of the most popular players. … [F]ew men possess greater baseball sense than Hinchman does.”1

Harry Sibley Hinchman was the fourth of five children born to Charles and Susan Hinchman. The Hinchman family had been in the Philadelphia area for at least three generations prior to Harry’s birth. While his birthplace is listed as Philadelphia, it was more likely to have been in neighboring Montgomery County, where the family is listed in the 1880 census. Harry’s Hall of Fame questionnaire also lists his birthplace as “Montgomery County (near Philadelphia).”2 His father worked in the steel and iron industry. Harry attended grade school and some high school in Philadelphia, where the family took up residence.

Hinchman learned baseball on the sandlots and began a semipro career in the late 1890s. He played with top-notch talent for Atlantic City in 1900 and Norristown in 1901 before joining the professional ranks in 1902 with the Ilion Typewriters in the New York State League. He spent three seasons as the second baseman for Ilion and was joined in 1903 and 1904 by his outfielder brother William. Harry played 363 games with Ilion, batted 1,320 times and recorded 280 hits for a .212 average. At this point in his career he was strictly a right-handed batter. The Typewriters had one losing season, 1903, during Harry’s tenure. Red Ames and Doc Scanlan anchored that pitching staff and went on to long major-league careers.

During the 1904 season, he wed Mathilda L.E. Metz in Philadelphia on July 20. Their honeymoon consisted of joining the team on a road trip in Scranton. Bill Hinchman led off the second inning with a home run. Following a base on balls, Harry launched a homer, his only one that season. The honeymoon was spoiled when Scranton rallied in the eighth for a 4-3 victory.3 Mathilda’s sister, Anna, joined them that fall and the couple welcomed a daughter named Alma a couple of years later.

In 1905 Ilion lost its franchise and Hinchman found himself with the Wilkes-Barre Barons in the NYSL. It was a season he wished he could forget or replay. The local paper put it simply: “Harry Hinchman has not measured up. …”4 The paper accused him of loafing on easy chances and of stepping into the bucket while at bat. Hinchman wanted a change of scene in 1906 and it was widely reported that he purchased his release from Wilkes-Barre. No money figures were offered. He was contacted by Binghamton and intended to join the team, but his commitment wavered when independent Williamsport came calling with a contract offer. After some serious thought, Hinchman choose to join Binghamton. He struggled again with the Bingoes and injured his right heel. The injury made it difficult for him to bat right-handed because it caused him great pain when the heel ground into the turf. Fearing that he would be released if he revealed the injury, he decided to bat left-handed and found that his hitting improved. In fact, when the heel mended he continued to bat left-handed. His .234 batting average was his best yet. In 1907, he became a switch-hitter.5

Hinchman prepped for his return to Binghamton by forming a barnstorming team in April. They played a series of games in Virginia before the players reported to their respective clubs. The Binghamton squad struggled in 1907, but Hinchman’s play was one of the few bright spots. In late July, the Cleveland Naps were beset by injuries to Elmer Flick, Bill Bradley, and Nap Lajoie. As fate would have it, the Naps were playing an afternoon exhibition in Albany, New York. Albany was slated to play Binghamton afterward. Naps manager Nap Lajoie invited Harry to join his brother Bill on the team and make the trip to Boston. The Naps left after the Binghamton game with Harry in tow. Harry took Lajoie’s spot at second base. Brother Bill was patrolling the outfield.

Harry debuted in Boston on July 29, 1907, playing second base and batting sixth. He had a single, handled 10 chances cleanly and helped on two double plays. Cleveland lost on the 29th and then dropped two of the next three to Boston. Harry committed an error in each of those games. The next stop was Philadelphia, where the Naps dropped four out of five games. Fortunately for the Naps, Lajoie and Flick returned to action. The road trip continued to Washington, where Hinchman went hitless versus Walter Johnson, but then slammed a double in the next game. He also committed two errors.

The Naps returned home for a three-game series with New York. Harry was dropped to eighth in the batting order. When Philadelphia came to town on August 15, Lajoie returned to second base. Harry would make one more appearance before the Naps sent him to Toledo of the American Association in September. There was a paperwork mistake in the transfer; the necessary waivers were not procured. The Pittsburgh Pirates took notice and put in a claim for Hinchman. After a good deal of wrangling, the National League office awarded Hinchman to Pittsburgh for $1,000. His rights were transferred back to Cleveland in late December. Harry would not return to the majors and closed out his career with 15 games played and a .216 batting average. He fielded a lowly .904 with nine errors.

Hinchman moved the family to Toledo and spent the next five seasons with the Mud Hens. Listed at 5-feet-11 inches and weighing 165 pounds, he never exhibited much power but developed into a pesky hitter. Thirty-nine stolen bases in 1909 attest to his quickness on the basepaths. He partnered with teammate Fred Abbott and purchased a billiard hall/bowling alley. This business venture might explain why Hinchman listed himself on the 1910 census as a plumber rather than ballplayer.

During his tenure, the Mud Hens were in the pennant race just once, in 1910. They finished second to Minneapolis, but were 15 games off the pace. Ducky Holmes started the 1910 season as manager. Relations between Holmes and the players were not “amicable” and Holmes aspired to purchase a franchise elsewhere. On June 4, Holmes was released and Hinchman was named manager. He would guide the team to a 64-56 record the remainder of the season.

The club owners were pleased with Hinchman’s work and named him manager for the 1911 season. Responsible for player transactions Hinchman found it necessary to find help at catcher. Fred Abbott was aging and had seen his batting average topple 95 points from 1908 to 1910. Hinchman sold his business partner to Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League. Abbott grumbled slightly because the PCL played a longer schedule, but his pay was going to stay the same.6

The 1911 Mud Hens roster was dotted with future (Ray Chapman) and past (Elmer Flick) Cleveland Naps players. For his part, Hinchman had a superb season at the plate. He hit .307 with 30 extra-base hits. Brother Bill at Columbus had superior power with 60 extra-base hits, but only a .295 average. Despite Hinchman’s strong hitting, the Mud Hens finished in sixth place with a 78-86 mark.

Hinchman returned to the Hens for 1912, but only as the second baseman. The managerial job was given to Topsy Hartsel, who guided the team to a second-place finish. Hinchman was dropped in early July but remained in the league with the St. Paul Saints. The 1913 Reach Baseball Guide lists him with 164 games and a .258 batting average. He added 28 extra-base hits and 27 stolen bases.

Hinchman spent the next two seasons with St. Paul before joining Association rival Kansas City in 1915. The Blues offense featured Jack Lelivelt and Pete Compton, who hit .346 and .343 to finish one-two in the batting race. Compton led the circuit with nine home runs. Hinchman hit .326 with 32 extra-base hits to place ninth in the league for average. Despite the fine hitting by the trio, the team could post only a 71-79 mark.

Father Time was catching up on Hinchman, who was well into his 30s. After nine seasons in the American Association, he was no longer wanted and dropped down to the Class A Western League, splitting 1916 between Lincoln and Sioux City. In Lincoln, he was reunited with Ducky Holmes, who proclaimed, “The fans will see a sweet hitter when Harry steps up to the plate.”7 Holmes looked like a genius judge of talent as Hinchman was the finest hitter in the league for the first month of the season. He tailed off and was “of comparatively little use to the Lincolnites”8 in June and July. He joined Sioux City on July 15. The 1917 Spalding Baseball Guide shows him playing 87 games and batting .296. The following year he went east to play for the Lawrence (Massachusetts) Barristers in the Class B Eastern League.

Lawrence folded after the 1917 season and Hinchman was appointed player-manager of the Waterbury Nattatucks, also of the Eastern League. Hinchman found the selection of talent to be thin with war fever gripping the nation. Baseball was declared “nonessential” on July 19 and the Eastern League ceased operations soon after. The Nattatucks returned to action in 1919, but Hinchman was no longer manager, just a 40-year old backup. He quit the team in August because of a lame arm. Hinchman would return to Waterbury in 1927 as manager. His tenure lasted only until mid-July.

Hinchman was out of baseball in 1920, but curiously listed himself on the census as “ballplayer.” The family resided in Toledo, where Alma attended school and sister-in-law Anna Metz clerked in a clothing store. Mathilda was in charge of the house. In 1921, Harry was hired as player-manager by the Chambersburg Maroons in the Class D Blue Ridge League. He played in 96 games and batted a robust .320, but the team finished fifth out of six entrants. He spent 1922 in Toledo before spending four seasons as manager of the Williamsport Billies in the New York Pennsylvania League.

Before accepting terms with Williamsport, Hinchman had a clause inserted into the contract that “there would be no interference from the stockholders or club directors. He was to have full charge of the playing end.”9 In Chambersburg the stockholders had insisted upon butting in and Hinchman wanted free rein. He quickly made arrangements with manager Bill McKechnie and the Pittsburgh Pirates to get players for his team. McKechnie wanted his youthful recruits to play for a manager who would teach them “real baseball.” Hinchman met the criterion.10 Led by shortstop Rabbit Benton (age 21) and outfielder Mule Haas (19), who both hit .342, the Billies won 82 games and finished in first place.

In 1924 the Billies again launched a serious batting attack; this time they were led by outfielder Roy Leavitt’s 18 home runs and Bill Hunnefield’s .347 average. They won 87 games and again held off York for the championship. The 1925 squad changed its name to Grays and featured good hitting again but also included multisport athlete Bob Fitzke and 18-year-old Dick Barrett on the pitching staff. Barrett would go on to win over 300 games in the minors. Once again, the pennant chase featured Williamsport and York. At the close of the season the Grays had a match with York and a doubleheader with Shamokin remaining. They were 1½ games back. Three victories forced a playoff that York won three games to one.

Hinchman had a well-earned reputation as a gentlemanly manager. His interactions with umpires were usually very professional and he did not employ the umpire-baiting tactics of some of his colleagues. He would question an arbitrator’s decision and stand up for his players, but the interactions were civil by baseball standards. Such was not always the case when Hinchman was a player. In 1906 in a game at Utica, a teammate was ejected by an Umpire Cusack and Hinchman came to the teammate’s defense. The situation quickly escalated and Hinchman struck the ump with a right cross. Cusack responded with an elbow to Hinchman’s head and three hooks. He was going after Harry to deliver more punishment before players held him back.11Did Hinchman learn the hard way that you do better with sugar than vinegar?

The 1926 Grays were led by future Pirates outfielder Adam Comorosky, who legged out 26 triples. The Grays quickly fell out of contention and finished 15 games off the pace. During the season, Hinchman’s reputation for civility was put to the test by an umpire named Mauder. The two had heated arguments in consecutive games. When Mauder made a call against the Grays on July 15, infielder Owen Kelly pushed Mauder and tossed a punch. In the ensuing confusion, Mauder claimed that Hinchman also threw a punch at him and recommended a $100 fine for Hinchman and $50 for Kelly.12 It is unclear whether the money was ever collected.

Hinchman severed his ties with Williamsport after the season and took the job at Waterbury. On July 18, the team had a 43-45 record. Soon after, Hinchman was either let go or arranged his release. The Reading franchise in the International League was co-owned by Joe McCarthy, who had played for Hinchman in Toledo. McCarthy wanted Hinchman to take over the lowly Reading Keystones, who were 21-78 at that time. Hinchman obliged and the Keystones defeated Newark 3-2 in Harry’s first game. The team finished with 43 wins. The following season, with Hinchman’s leadership and players from the Chicago Cubs organization, the Keystones posted 84 wins and a first-division finish. In 1929 and 1930 the squad finished in seventh place.

Hinchman retired from baseball and entered the bowling-alley business again. He was lured back to the diamond in 1932 when Williamsport offered him the managerial position on May 15 after original manager Herb Moran fell out of favor. Hinchman managed for two months before having to resign. Heart disease was sapping his strength. Glen Killinger was named as his replacement. Hinchman did have the unique opportunity to manage against his nephew Bill Jr. who played for Binghamton. Harry returned to the bowling-alley business in Toledo, but by Christmastime he was bedridden with a bad heart. He died on January 19, 1933, and was laid to rest in the Toledo Memorial Park Cemetery.

Last revised: April 16, 2021 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, statistics are from Baseball-Reference. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball provided team records.

Notes

1 “Tribute to Former Baron,” Wilkes-Barre Record, September 5, 1913: 17.

2 Ancestry.com provided the 1880 census. The Hall of Fame questionnaire was filled out by Harry’s daughter Alma.

3 “New York State League,” Scranton Truth, July 22, 1904: 12.

4 Wilkes-Barre News, June 1, 1905: 5.

5 ‘Benefited by an Accident,” Pittsburgh Press, August 2, 1907: 18.

6 “Turns Loose His Partner,” Pittsburgh Press, January 21, 1911: 8.

7 “Slugging Player Bagged by Ducky,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, February 16, 1916: 9.

8 “Harry Hinchman Dropped,” Lincoln Daily News, July 10, 1916: 9.

9 “Hinchman to Pilot Williamsport, After Buc Rookies,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, April 24, 1923: 13.

10 Ibid.

11 “Can Punch as Well as Umpire,” Scranton Republican, September 21, 1906: 8.

12 “Umpire Recommends Heavy Fines on Two Williamsport Players,” Scranton Republican, July 16, 1926: 19. The article noted that the umpire had played in the American Association with Toledo. No “Mauder” is cataloged in Baseball-Reference. He may have spelled his name Maurer.

Full Name

Harry Sibley Hinchman

Born

August 4, 1878 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

January 19, 1933 at Toledo, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.