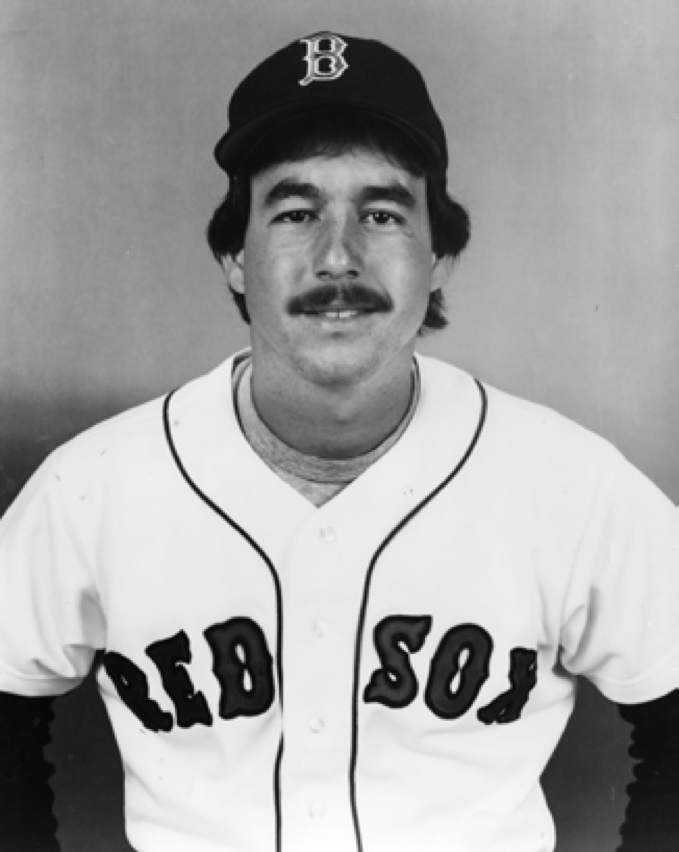

Al Nipper

If anyone knew the definition of pain, it was right-hander Al Nipper, who toiled for parts of seven seasons in the big leagues (1983-1988, 1990), most notably for the Boston Red Sox. His list of injuries and maladies seems hard to fathom: nerve problems in his neck and elbow, chronic elbow inflammation, a blood disorder eventually diagnosed as stomach ulcers and anemia, a serious injury to his right knee during a collision at home plate that almost severed a muscle, back spasms requiring traction, toe pain, and bone chips in his left knee. Somehow, he found time to win 46 games and log almost 800 innings. “I didn’t have the best God-given ability and was fortunate enough to hang around as long as I did,” said Nipper, who relied primarily on breaking balls and a knuckler for his success. “I had to work to know the hitters. I had to be a student of the game to maximize my ability.”1

If anyone knew the definition of pain, it was right-hander Al Nipper, who toiled for parts of seven seasons in the big leagues (1983-1988, 1990), most notably for the Boston Red Sox. His list of injuries and maladies seems hard to fathom: nerve problems in his neck and elbow, chronic elbow inflammation, a blood disorder eventually diagnosed as stomach ulcers and anemia, a serious injury to his right knee during a collision at home plate that almost severed a muscle, back spasms requiring traction, toe pain, and bone chips in his left knee. Somehow, he found time to win 46 games and log almost 800 innings. “I didn’t have the best God-given ability and was fortunate enough to hang around as long as I did,” said Nipper, who relied primarily on breaking balls and a knuckler for his success. “I had to work to know the hitters. I had to be a student of the game to maximize my ability.”1

Boston sportswriter Peter Gammons once called Nipper a pitcher and not a thrower, and suggested that he was the personification of the “Baltimore Orioles pitching manual” with his cerebral and fundamentally sound approach to the game.2 Not blessed with the natural talent of teammates Roger Clemens, Bruce Hurst, or Oil Can Boyd, Nipper was known for his large array of pitches, including a screwball, slider, curve, knuckleball, sinker, forkball, fastball, and changeup, all of which he could throw at different release points, from overhand to three-quarters, and at varying speeds. His nickname, “the man with a thousand pitches,” needs no clarification. Baseball lifer Don Zimmer, Nipper’s manager with the Chicago Cubs in 1988, once claimed that only his former teammate with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Russ Meyer, threw more kinds of pitches.3

Albert Samuel Nipper was born on April 2, 1959, in San Diego, California, the second and final child of Frederick and Gertrude (Schmid) Nipper, both of German heritage. In the mid-1960s the Nippers relocated to Hazelwood, a northwest suburb of St. Louis, Missouri, where Al became an unabashed Cardinals fan. “I always wanted to be a big leaguer,” said Al, who claimed he went to 30 to 40 games a season at Busch Stadium.4 “I’d go sit down by the bullpen before every game so I could watch the pitchers warm up,” he continued. “I learned from watching.”5 He idolized Tom Seaver of the New York Mets, and collected books on pitching to teach himself proper mechanics and delivery. In his teenage years, Al played baseball from spring to late autumn, progressing through the area’s youth leagues, and then starring as a pitcher at Hazelwood West High School. In 2011 he was in the school’s inaugural class for its hall of fame.6

Upon graduating in 1977, Nipper enrolled at Northeast Missouri State University (renamed Truman State University in 1996), located in Kirksville, about 200 miles northwest of St. Louis. During his three years with the Bulldogs, Nipper posted a misleading 10-18 record, and 2.65 ERA; he completed 18 of 23 starts and struck out 152 in 160 innings for teams that had a combined 26-46 record.7 Nipper began to attract the attention of baseball scouts in 1979 when he carved out an impressive 0.98 ERA in 55⅓ innings and was named to the Missouri Intercollegiate Athletic Association All-Star squad. That same year he led his St. Louis-based amateur team to the national tournament of the National Baseball Congress in Wichita, Kansas.8

The Boston Red Sox chose Nipper in the eighth round (205th overall pick) in the 1980 amateur draft. Assigned to Winter Haven in the Class-A Florida State League, Nipper surprised the Red Sox by going 6-4 and posting a 2.54 ERA in 85 innings, while their first-round draft choice, lefty Mike Brown, struggled (3-4, 4.31). Back with Winter Haven in 1981, Nipper tossed 28 consecutive scoreless innings early in the season, and was named to the league’s all-star team. He won 14 games for the last-place club and paced the circuit in ERA (1.70), complete games (15), and innings (212, a career best).

Promoted to Double-A Bristol in the Eastern League in 1982, Nipper suffered the first of what seemed to be annual injuries that limited his effectiveness. Early in the campaign he hurt his neck (diagnosed as thoracic outlet syndrome), causing a nerve problem in his right elbow, and he limped to a disappointing 6-7 record and 3.68 ERA. He attempted to pitch through the pain, but in doing so aggravated the injury, which bothered him for the next two years. “An injury like mine takes time to come back and rebuild all of the strength,” said Nipper in 1984. Not only was the injury a red flag for Boston; his Bristol teammates Mike Brown (9-6, 2.45 ERA) and Oil Can Boyd (14-8, 2.81) seemed primed for the big leagues.

The 24-year-old Nipper started the 1983 season with Bristol and was promoted in midseason to Triple-A Pawtucket in the International League when Boyd was called up to the Red Sox. Nipper won a club-high nine games and posted a 4.45 ERA in 109⅓ innings for the league’s cellar-dwellers.

En route to its worst season since 1966, Boston called up Nipper when the rosters expanded in September. In his debut, on September 6, he hurled one inning of relief and walked one in a loss to the eventual World Series champion Baltimore Orioles; they also handed Nipper a loss in his first start, a week later. Elbow inflammation kept Nipper sidelined until the final game of the season, one which marked an end of an era in Red Sox history as Carl Yastrzemski retired after 23 seasons. Somewhat lost in the day’s emotional festivities was Nipper’s complete-game nine-hitter to defeat the Cleveland Indians, 4-1, at Fenway Park.

As spring training opened at the Red Sox camp in Winter Haven in 1984, the media’s attention focused on 21-year-old rookie Roger Clemens. Nipper was given little chance of making the squad given that five starters from the previous year were back (Hurst, Bob Ojeda, Boyd, Brown, and 29-year-old Dennis Eckersley; John Tudor had been traded in the offseason); however, Nipper surprised skipper Ralph Houk, who unexpectedly chose him as his long reliever instead of veteran Rich Gale. “I’m elated the pressure is off,” said Nipper.9 The key to his success in spring training was a screwball. “[It] helps me tremendously against left-handed hitters,” said the pitcher. “I can get them looking outside and then bust a fastball inside.”10 Little used through May and still bothered by elbow tenderness, Nipper moved into the starting rotation in June after Eckersley was shipped to the Chicago Cubs for Bill Buckner and Mike Brumley, and Brown was optioned to Pawtucket. Hit hard in his first two starts, Nipper transformed into the “surprise of the staff,” according to beat reporter Gary Santaniello.11 During a stretch of eight starts, Nipper won three of five decisions and carved out an impressive 2.71 ERA in 63 innings while batters hit at just a .218 clip against him. “I’ve had to go out and challenge hitters,” said the 25-year-old, “and that’s what I’ve done.”12 While the Red Sox trailed the Detroit Tigers by double digits in the AL East, Nipper emerged as the team’s most consistent hurler. Over a seven-start stretch from August 14 to September 15, he won a career-best six straight decisions and posted a 2.33 ERA in 58 innings. “Gradually this year I’ve been able to build my arm back,” said Nipper. “[N]ow I’m throwing every bit as well as I did three years ago. Every start I’ve gotten a little more confidence.”13 While sportswriter Peter Gammons claimed that Nipper was one of the best at changing speeds in the AL, pitching coach Lee Stange liked his control and the way he mixed up his pitches, saying, “He’s not an overpowering pitcher, but he gets his curve and the slider over and can spot the fastball.”14 For the fourth-place Red Sox, Nipper finished with an 11-6 record and a 3.89 ERA (best among starters), and logged 182⅔ innings. The Boston chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America named him co-rookie of the year with Roger Clemens (9-4, 4.32). Nipper finished seventh in voting for the AL Rookie of the Year Award.

During his tenure with Boston (1983-1987), Nipper had a reputation as a fun-loving prankster and master of the pie-in-the-face-routine when teammates were being interviewed. He roomed with Clemens, seemingly got along with everyone, and helped forge a team identity by defusing tensions with his humor. “I guess I was one of the few people who understood Oil Can,” said Nipper of his relationship to the controversial pitcher. “I always knew where he was coming from.”15 Boston sportswriter Nick Cafardo described Nipper as “the media’s go-to guy” who was always willing to give the inside scoop on the team and explain the inner workings of the club, as well as to defend his teammates.16 He also had peculiarities, such as one he copied from Steve Carlton. He buried his right hand in a barrel of rice and pushed his fingers down as far as they could go in order to build strength.17 But Nipper was not a flake; rather, he took a studious approach to the game. He was an early advocate of studying films to gain a competitive advantage, and pored over films of himself and his opponents in the offseason to look for ways to improve.18

Nipper had the scare of his life in 1985. He reported to spring training early for new manager John McNamara and pitching coach Bill Fischer, but soon noticed that he was quickly fatigued from working out. An examination by the team physician, Dr. Arthur Pappas, revealed a low blood count and fears rose that the pitcher might have leukemia. Nipper was eventually diagnosed with a serious stomach ulcer and anemia, and missed almost all of spring training. “One thing this did was change my perspective on life,” said Nipper, who came off the disabled list on April 15. “I appreciate having my health back. You hear a lot of griping, especially among ballplayers. We make a lot of money, and we’re pampered and babied, and we get bent out of shape about a lot of the little things.”19

Physically weak, Nipper struggled as the 1985 season got under way, losing five of his first six decisions with a 5.40 ERA through May. He seemed to reach his stride in June, winning three straight starts (two of which were complete games), but then developed serious back spasms. As they worsened in July, Nipper was hospitalized and placed in traction. “[It] was just a weird year for me. I was always waiting for something next to happen. I was fighting everything,” said Nipper, who battled shoulder and toe pain in August and September.20 Through it all, Nipper maintained an even keel, and his humor. “I was actually waiting for (the elbow) to blow out, but it never did.”21 The season was a disappointment for the Red Sox, as well as Nipper. The third-highest-scoring offense in the AL was offset by the league’s most porous defense and Boston slipped to fifth place. “I wasn’t consistent in my mechanics,” said the 26-year-old Nipper, who finished with a 9-12 record and a 4.06 ERA, and surrendered 82 walks in just 162 innings.22 Rumors of Nipper’s trade in the offseason to the Chicago White Sox for boyhood hero Tom Seaver proved to be false; however, the Red Sox acquired the aging right-hander in June 1986 for utilityman Steve Lyons.

“I feel better mentally, because I know I’m fine physically,” said Nipper during spring training in 1986.23 He added a knuckleball to his arsenal of breaking balls, changeups, and an occasional fast one. Nipper had played around with the knuckler since college, and was encouraged to master the pitch by pitching coach Bill Fischer, a former knuckleball thrower.24 The Sporting News tabbed Nipper, along with Cleveland’s Tom Candiotti, as the “best bet” to carry on the knuckling tradition of Phil and Joe Niekro and Charlie Hough.25 Nipper unveiled the knuckler in his fourth start of the season, a masterful four-hit complete-game victory against reigning Cy Young Award winner Bret Saberhagen and the Kansas City Royals. “I might not have that good stuff, but at least I’ll feel confident enough I’ll trick ’em or find a way to get by,” said Nipper, who compared himself to Charlie Liebrandt and Frank Tanana. “I’ve got to pitch inside to be effective. I’ve got an average fastball, but with all the other breaking stuff I throw, it makes my fastball look a little quicker.”26

Just when Nipper seemed to have some momentum, he suffered what Boston sportswriter Joe Giuliotti called a “career threatening” injury against the Texas Rangers on May 18 at Fenway Park. “I was [ticked off] about throwing one to the backstop with Toby Harrah up and I convinced myself I wasn’t going to let [Larry Parrish on third] score,” explained Nipper. “So I blocked the plate and he came and got me in the [right] knee. I made the tag and held up the ball to show the umpire. Then, my leg just collapsed.”27 Nipper suffered a deep, four-inch gash in his vastus medialis (one of the three major muscles in the kneecap) and was bleeding profusely. “It was a terrible sight,” said McNamara.28 Carried by teammates off the field, Nipper was taken to the hospital and underwent emergency surgery that evening. Widely expected to miss as much as two months, Nipper returned five weeks later and defeated the Yankees in his first start, on June 25, to give the Red Sox a five-game lead in the Al East. The fourth starter, behind Clemens (24-4, 2.48), Boyd (16-10, 3.78), and Hurst (13-8, 2.99), Nipper posted a 10-12 record with an inflated 5.38 ERA as Boston captured its first division crown since 1975.

“It was a good club and no one really expected us to do anything in ’86,” said Nipper, who did not see action in the ALCS as Boston overcame a three-games-to-one deficit to defeat the California Angels. “We had a nucleus of good players and good team chemistry.”29 A prohibitive underdog against the New York Mets, winners of 108 games, in the World Series, Boston won the first two games, at Shea Stadium in New York. Described by syndicated sportswriter Moss Klein as the staff’s “weak link,” Nipper started Game Four, at Fenway Park, and held the high-powered Mets to three runs over six innings but was collared with the loss in a 6-2 defeat to even the series at two games each.30 After the game, McNamara was widely criticized and second-guessed for starting Nipper, who had struggled in his final 10 starts of the season (6.97 ERA).31 His next appearance came in the deciding seventh game. After the Mets took the lead in dramatic fashion against Calvin Schiraldi in the seventh inning (and collared him with the loss in the final two games of the series), Nipper suffered through a forgettable relief appearance in the eighth inning. He yielded a home run to Darryl Strawberry, the first batter he faced, and was charged with three hits and two runs, and issued an intentional walk while retiring just one batter as the Mets won, 8-5, to capture their first title since the “Miracle Mets” of 1969. “I sat at my locker for an hour after that game with my head staring down at the ground,” said Nipper. “That’s how bad I felt.”32

At 6-feet-1 and about 185 pounds, Nipper did not have a commanding presence on the mound like Clemens and Hurst, both of whom stood 6-feet-4 and weighed in excess of 200 pounds; however, Nipper had a no-nonsense, combative approach to pitching, and never backed down from a hitter. He was peeved in Game Seven of the World Series by what he considered Strawberry’s slow trot around the bases after his home run in the eighth inning and the way Red Sox players were treated. “I don’t care if I ever see New York again. The fans there are animals,” he said, referring to an incident when traveling secretary Jack Rogers was hit by a flying beer bottle. “They don’t have any class whatsoever.”33 When the Red Sox and Mets faced off in an exhibition game the following spring, on March 14, Nipper took “old school” revenge by plunking Strawberry, and benches cleared, though no brawl ensued. Commissioner Peter Ueberroth fined Nipper, who denied throwing at Strawberry. “I tried to come up and in with a fastball and it got away,” he said. “I think he overreacted.”34

In 1987 Nipper began relying on his knuckleball more often. At times he “baffled” opponents, such as the Yankees, against whom he tossed consecutive complete-game five-hit victories in June;35 at other times, he was clobbered. (In 11 of his career-high 30 starts he failed to go five innings.) He suffered a severely pulled rib cage muscle in June, landed on the DL, and missed almost four weeks. Other than Clemens, who captured his second consecutive Cy Young Award, the rest of the Red Sox hurlers seemed to be in a collective funk as the staff finished 12th out of 14 teams in ERA, contributing to the club’s disappointing 78-84 record and fifth-place finish. Nipper finished with an 11-12 record and 5.43 ERA in 174 innings; he surrendered 30 homers. “[He’s] a No. 5-type starter, a gutsy pitcher who gets by on guile,” wrote The Sporting News, “but he doesn’t get by enough.”36 On December 8 Nipper and Schiraldi were shipped to the Chicago Cubs in exchange for closer Lee Smith.

Nipper’s short, injury-filled tenure with the Cubs was an unmitigated disaster. Hobbled by a hamstring injury in spring training, he began the season in the bullpen before moving into the rotation. After a promising six-start stretch (2.43 ERA in 37 innings), he landed on the DL with elbow soreness in late May. Limited to occasional relief duty when he returned a month later, he made five starts before the pain ended his season prematurely in mid-August, after he logged just 80 innings, but posted a promising 3.04 ERA. Nipper suffered yet another injury the following spring training when physicians diagnosed bone chips in his left knee. “I can’t win a job,” said a frustrated Nipper, “but there’s nothing I can do. I can’t land on [my left leg] in my follow-through. They can’t do an arthroscopy because the bone chips are on the tendon. If I pitch too soon, I can hurt my elbow again, so I’m in a Catch-22.”37 The Cubs released him on March 28, 1989, after which he filed a grievance with the players’ union. Nipper argued that he was entitled to his full salary, while the team claimed he had been injured prior to camp and was eligible for only a fraction of it. According to the Chicago Tribune, the two sides reached an agreement in June under which the Cubs paid Nipper half of his estimated $350,000 salary.38

After operations on his knee and elbow, Nipper missed the entire 1989 season. He accepted the Cleveland Indians’ invitation to join them in spring training in 1990 and made the team as a free agent. After four mainly ineffective relief appearances, he was optioned to Colorado Springs in the Pacific Coast League. He was recalled in June and made his final five starts in the big leagues (winning two of them) before being sent back to Colorado Springs. Released in the offseason, he had a brief stint with the St. Louis Cardinals’ affiliate in the American Association, the Louisville Redbirds, in 1991, before retiring.

A courageous competitor, Nipper finished with a 46-50 record, started 124 of 144 games, completed 21, and posted a 4.52 ERA in 797⅔ innings. He whiffed 381 and walked 303.

Nipper made a smooth transition to his post-playing days. In 1992 he inaugurated his coaching career that (as of 2015) is in its fourth decade by accepting the Red Sox’ invitation to serve as a minor-league pitching coach. “[I] knew I always wanted to get into coaching even when I played,” he said.39 His former manager, Ralph Houk, was not surprised. “He’s the type of guy who would be a good pitching coach because he got the most out of his abilities. He didn’t throw very hard, but he knows how to pitch. He asked a lot of questions.”40 In July 1995 Nipper returned to the big leagues when he was named Boston’s pitching coach for the remainder of the season. As he did during his playing days, Nipper had a pragmatic approach to coaching. “As coaches, we wear lots of different hats. We’re psychiatrists, confidants, leaders, and many other things,” he said, asserting also that the most important aspect was earning the players’ trust.41 He also served as pitching coach for the Texas Rangers (1998-2000) and Kansas City Royals (2001-2002). After working in the Boston and Detroit organizations, Nipper was the pitching coach the Triple-A Toledo Mud Hens in 2014. Coincidentally, the manager of that team was Larry Parrish, whose collision with Nipper at home plate in 1985 left a visible reminder on the pitcher’s knee. In 2015 Nipper was named pitching coach for the Kansas City Royals’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League, the Omaha Storm Chasers.

As of 2015, Nipper lived with his wife, Leslie (Schweppe) Nipper, in Chesterfield, a suburb of St. Louis.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author consulted:

Baseball-Reference.com.

Retrosheet.org.

SABR.org.

Al Nipper player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Jon Goode, “Catching up with … Al Nipper,” SouthCoastToday (New Bedford, Massachusetts), July 3, 2005. southcoasttoday.com/article/20050703/News/307039964.

2 Peter Gammons, “Learned Experience,” Boston Globe, July 14, 1984.

3 Jerome Holtzman, “Cubs’ jack of all pitchers but master of none must search for his niche,” Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1989, B3.

4 Gammons.

5 Ibid.

6 “Inaugural Class at Hazelwood West High School to induct six honorees,” Hazelwood School District. hazelwoodschools.org/News/Pages/InauguralHallofFameatHazelwoodWestHighSchooltoinductsixhonorees.aspx.

7 Nipper’s college statistics are from 2005 Truman State Baseball Media Guide: gobulldogs.truman.edu/mediaguide/men/baseball/05baseballmg4.pdf.

8 “Liberal Wins at NBC,” Garden City (Kansas) Telegraph, August 16, 1979, 6.

9 Hugh McGovern, “Al Nipper Earns Spot in Sox Pen,” Evening Gazette (Worcester, Massachusetts), March 27, 1984.

10 McGovern.

11 Gary Santaniello, “Nipper becomes Stopper For Sox,” Telegram (Worcester, Massachusetts), 1984 article (no further date) from player’s Hall of Fame file.

12 The Sporting News, August 6, 1984, 16.

13 Gammons.

14 The Sporting News, September 17, 1984, 14. According to Gammons, Nipper joined Scott McGregor, Doyle Alexander, Frank Tanana, and Mike Boddicker as the best at changing speeds; Rich Thompson, “Nipper gets major league lesson in win,” Boston Herald, July 7, 1984.

15 Nick Cafardo, “Groomed to be a coach,” Boston Globe, July 23, 1995.

16 Cafardo, “Groomed to be a coach.”

17 The Sporting News, January 21, 1985, 38.

18 Ibid.

19 Bill Richardson, “Nipper glad to be battling hitters again,” Kansas City Times, April 15, 1985.

20 Jim Lazar, “New Year, a new attitude for a determined Nipper,” Salem (Massachusetts) Evening News, March 19, 1986.

21 Nick Cafardo, “Everything OK for Nipper except score,” The Telegraph (Nashua, New Hampshire), August 13, 1985, 11.

22 Win Bates, “Nipper’s ’86 spring: ‘Viva la difference,’ ” The Enterprise (Brockton, Massachusetts), March 19, 1986.

23 Bates.

24 “Nipper Goes to Knuckleball, Pitches Red Sox Past Yankees,” Schenectady (New York) Gazette, June 29, 1987, 27.

25 The Sporting News, March 31, 1986, 32.

26 Larry Whiteside, “Nipper knuckles down,” Boston Globe, April 28, 1986.

27 Cafardo, “Groomed to be a coach.”

28 Joe Giuliotti, “Nipper won’t be ready until July,” Boston Herald, May 19, 1986,

29 Goode.

30 The Sporting News, October 27, 1986, 18.

31 The Sporting News, November 3, 1986, 11.

32 Cafardo, “Groomed to be a coach.”

33 Ibid.

34 “Nipper fined for Mets incident, Red Sox for a lack of control,” March 28, 1987. Unattributed article in player’s Hall of Fame file.

35 The Sporting News, July 22, 1987, 19.

36 The Sporting News, December 21, 1987.

37 The Sporting News, March 27, 1989, 35.

38 Fred Mitchell, “Bit and Pieces,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1989, B7.

39 Goode.

40 Cafardo, “Groomed to be a coach.”

41 Nick Cafardo, “Thinking man’s coach is Nipper,” Boston Globe, March 1, 1996.

Full Name

Albert Samuel Nipper http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695

Born

April 2, 1959 at San Diego, CA (USA)

Died

, http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695 at http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695, http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695 (http://dev.sabr.org/?p=61695)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.