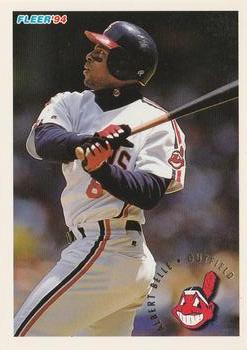

Albert Belle

“Joey is extremely smart. He’s great with figures and crossword puzzles. He could spell backwards when he was five. Did you know my Joey was an Eagle Scout? He took French in high school, finished sixth in his class of 266. I brought him up to excel in everything. He wants to be perfect.” — Carrie Belle, Albert Belle’s mother, Sports Illustrated, June 24, 1991.

“Joey is extremely smart. He’s great with figures and crossword puzzles. He could spell backwards when he was five. Did you know my Joey was an Eagle Scout? He took French in high school, finished sixth in his class of 266. I brought him up to excel in everything. He wants to be perfect.” — Carrie Belle, Albert Belle’s mother, Sports Illustrated, June 24, 1991.

Strike 1: It’s impossible to be perfect, or bat 1.000 over the course of a 12-year major-league baseball career. Which leads to …

“Sometimes he throws coolers around. Sometimes he breaks phones in the clubhouse. There are cookies all over the place. This guy is so unbelievable, he can go three for three going into his at-bat and pop out, and he’s still throwing cookies around.” — Former Indians teammate Omar Vizquel to the Associated Press, October 23, 1995.

Strike 2. In Belle’s case, imperfection led to temper tantrums, shattering locker-room sinks, ripping thermostats off clubhouse walls, and firing expletives at media members. Which amped up Belle’s anger inside and …

“Throughout his major league career Albert Belle has demonstrated a distinct pattern: When the surly slugger gets P.O.’d, baseballs get K.O.’d.” — Mark Bechtel, Sports Illustrated, July 27, 1998.

During his tumultuous career, Albert Jojuan Belle (born August 25, 1966, in Shreveport, Louisiana) almost always played pissed off. And his career statistics (a .295 batting average, a .369 on-base percentage, and averages of 32 home runs and 103 RBIs per season) second that emotion.

But when discussing Belle and/or his playing career, words speak louder than numbers. Take your pick of adjectives. Abusive and articulate. Dominant and divisive. Intimidating and intellectual. Consistent and cursing.

Belle has fond memories of growing up. “I was blessed to grow up with parents who possessed different strengths and skills,” Belle wrote in an op-ed piece for the Baltimore Sun.1 “Mom was and still is the ‘glue’ of the family, but Dad (also named Albert) was the enforcer and ‘silent pillar of strength.’ Mom encouraged academics and culture, and Dad always promoted athletics. Both gave me and my brother all they had.” Belle’s mother was a math teacher and his father, in addition to his football and baseball coaching duties at another Shreveport-area high school, was also an educator.2

The elder Belle pushed his twin boys hard. “To this day, I believe my late-night batting practices during my high school years were what made the difference in helping me arrive at the Major Leagues. After high school baseball practice, I would go home, eat dinner, and tackle homework. Dad would usually arrive home after a long practice with his high school team. After talking to Mom for a few minutes, he would poke his head in our room. That was our signal. My brother and I would immediately bounce up and jog out of the house up to the local junior high school, with Dad driving behind us. Dad would throw us hundreds of balls all night long.”3

After an all-state career and National Honor Society merit at Huntington High School in Shreveport, Belle attended Louisiana State University (1985-87) in Baton Rouge, where he set school career marks for home runs (49), total bases (392) and RBIs (172).4

But Belle’s inability to control his temper appeared on a public stage for the first time during a game at the 1987 Southeast Conference tournament. Belle attempted to run down a fan who was shouting racial slurs at him. Two of his teammates tackled him and he was suspended for the College World Series by Tigers coach Skip Bertman.

Tick, tick, tick.

It wasn’t the last time Belle confronted a fan. On May 11, 1991, while with the Indians, he drilled Jeff Pillar in the chest with a fastball fired from 15 feet away after Pillar yelled, “Hey Joey, keg party at my house after the game.”5 Two years later, on September 23, 1993, Belle was with some teammates at a Cleveland nightclub when he hit William Kelly twice in the face with a ping pong paddle after Kelly chanted, “Joey, Joey”6 (the name Belle went by before his 10-week stay at an addiction treatment center in 1990).7

The Indians selected Belle with their first pick in the 1987 amateur draft. Belle spent parts of five seasons in the minor leagues. Splitting time between Kinston and Waterloo during the 1988 campaign, Belle belted 17 home runs with 54 RBIs and a .293 batting average. The next year he jacked 20 home runs for Double-A Canton-Akron, earning a promotion to the major leagues. In 62 games Belle struggled with his batting average (.225) but did club seven home runs while driving in 37 runs. He was only 22 years old.

Belle’s 1990 season was interrupted by his rehab stay. Re-emerging clean, Joey Belle began going by his given first name, Albert, upon leaving the facility. He made the Tribe’s roster for good at the start of the 1991 season. He slammed 28 home runs in 123 games that year, driving in 95 runs while batting .282. He was just getting started.

Belle’s 1990 season was interrupted by his rehab stay. Re-emerging clean, Joey Belle began going by his given first name, Albert, upon leaving the facility. He made the Tribe’s roster for good at the start of the 1991 season. He slammed 28 home runs in 123 games that year, driving in 95 runs while batting .282. He was just getting started.

From 1992 to 1996, there was no more dominant — or feared — batsman than Belle. His five-year averages of .303 (batting), 41 home runs, and 123 RBIs were neither equaled nor surpassed by anyone. He was named to four American League All-Star teams during that span.

Of course, Belle being Belle, there were some speed bumps along the way. In the strike-shortened 1994 season (teams refused to take the field for any of the scheduled August 12 contests and forced the cancellation of the rest of the season and the World Series) he had one of his bats confiscated by the umpiring crew during a July 15 Central Division showdown with the Chicago White Sox. Chicago manager Gene Lamont, acting on a tip, asked the umpires to check the bat for cork. A bat filled with cork can be swung faster because the cork makes it lighter and gives the baseball lift.

Following league policy, the umpires locked the bat in the umpires’ room. After the incident, Cleveland pitcher Jason Grimsley, knowing that corked bats were part of Belle’s arsenal, snaked his way through the maze of ductwork and ceiling tiles in the bowels of Comiskey Park II. “My heart was going 1,000 miles an hour,” Grimsley said. “And in (to) the umpire’s dressing room I went. I just rolled the dice. A crap-shoot.”8

Grimsley said he quickly dropped from the top of a refrigerator to a counter and down, and immediately spotted Belle’s bat in an umpire’s locker. He made the exchange, as imperfect as it was: According to other members of the Indians’ organization, Grimsley had to switch Belle’s bat with one belonging to Paul Sorrento because every one of Belle’s bats was corked.9 As often was the endgame with Belle, he was suspended for seven games (reduced from 10).

During the strike-delayed 1995 campaign, Belle became the only major leaguer to sock 50 home runs and 50 (52) doubles in the same season, which was all of 144 games (Belle played in 143 games that year). He tied Babe Ruth’s 1927 record for home runs in September with 17.10 Like Ruth, Belle was the best player on the best team in baseball.

Despite his offensive fireworks, Belle placed second in the 1995 American League Most Valuable Player race, behind the inferior stat line of Boston first baseman Mo Vaughn. “Actually I’m surprised I got as many votes as I did,” said Belle, who received 11 first-place votes to Vaughn’s 12. “I’m kind of upset that they give baseball writers all this power when other media people who were former ballplayers should be involved in the voting, too. Maybe it should be 50-50 with those guys and the writers. Or maybe not let the baseball writers vote at all.”11

The Indians ended a 41-year World Series drought when they faced the Atlanta Braves and their future Hall of Fame-loaded starting rotation of Tom Glavine, John Smoltz, and Greg Maddux. Though the Braves won in six games, Belle made headlines, although not necessarily for his offensive prowess. (Though he hit just .235, Belle had two home runs, four RBIs, four runs scored, and seven walks for an eye-popping 1.047 OPS).

During batting practice before Game Three, which for Belle was akin to a church service, he became annoyed at the number of media members in the Indians dugout. According to NBC reporter Hannah Storm, “Initially, he screamed at all the media to get out of the dugout in language that was horrible. Two or three men left. They were frightened. I was the only one who stayed, because I was waiting to do an interview with Kenny Lofton. When I stayed, he directed his tirade at me.”12

Major League Baseball was slow to react. While it could not have approved of Belle’s actions, the strong arm of the players union lurked in the background. For his part, Belle felt he should be neither fined nor suspended. “If that’s what (Bud Selig) wants to do, I’ll just tell him that’s bull (bleep) if I have to be suspended for trying to get back some (batting) space that he as commissioner should have given us in the first place.”13

Belle’s logic was not shared by Selig. He ruled on February 29, 1996, that the outfielder had a choice: a $10,000 fine or a 10-day suspension. Belle reluctantly chose the former punishment.

Belle’s agent, Arn Tellem, not surprisingly agreed with his client. “The fine is without any precedent and is totally unjustified,” he said. “But we had no choice but to accept the fine given that (Selig) had no remedy to go before someone neutral to hear this matter. It would be like Marcia Clark deciding the fate of O.J. Simpson.”14

Belle’s 1995 was not over until Halloween Night, when he jumped into his truck to chase down kids from his neighborhood who had egged his house.15 He was convicted of reckless operation of a motor vehicle and fined $1,000 for that bit of horseplay.16

During his 1996 free-agent walk year with the Indians, Belle continued to get the job done on the field. His 148 RBIs led the league. He clubbed 48 home runs while batting .311. Belle received his fourth straight Silver Slugger Award, finished third in the MVP voting, and won a five-year, $55 million contract with the Chicago White Sox. Just like the Babe, Belle was now baseball’s highest-paid player.

For Belle, the move to a division rival represented a new beginning after 10 years and a lot of uneasiness with the same organization. His unhappiness over the Indians’ 1995-1996 offseason moves was still evident one year later. “After we went to the World Series (in ’95), I told them: `Please keep this team together. We’ll win the World Series a few times, but only if it’s kept together.’ All they needed to do was re-sign Paul Sorrento and Kenny Hill and our offseason moves would’ve been over. We would’ve been set. We would’ve brought the same team back and I’m telling you we would’ve won more games, gone back to the Series and won it. When you go to a World Series, you can’t tinker with the chemistry of a team because you fight so hard to get that kind of chemistry.”17

At least one of Belle’s ex-teammates begged to differ. “I got tired of answering questions about him,” said shortstop Omar Vizquel during 1997 spring training. “He was in his own little world. He’s a great player, but he didn’t contribute to team chemistry. And team chemistry is important.”18

Indians manager Mike Hargrove said, “Some of the things surrounding Albert were not good, but you take the good with the bad.”19

The 1997 Indians did not win as many games as Belle’s last Tribe team had, but still captured the AL Central by six games over his new squad. After taking care of the Yankees and Orioles in the playoffs, the Clevelanders advanced to their second World Series in three years, dropping Game Seven and the Series to the Florida Marlins.

Belle had his first of two productive seasons with Chicago. In 1997 he recorded his sixth consecutive season of hitting at least 30 home runs (30) and driving in at least 100 runs (with 116). The year after, he increased that streak to seven years with 49 homers and a career-high 152 RBIs. In two years, the White Sox slugger compiled a .301 batting average. At age 31, he was among the game’s elite, and raised his salary ante to get paid like it.

Belle had his first of two productive seasons with Chicago. In 1997 he recorded his sixth consecutive season of hitting at least 30 home runs (30) and driving in at least 100 runs (with 116). The year after, he increased that streak to seven years with 49 homers and a career-high 152 RBIs. In two years, the White Sox slugger compiled a .301 batting average. At age 31, he was among the game’s elite, and raised his salary ante to get paid like it.

Belle’s original contract with the White Sox called for him to remain among baseball’s top three paid players. The White Sox refused to negotiate, giving Belle and his agent a narrow window to shop his services. They found a willing suitor in the Baltimore Orioles, who showered Belle with a five-year, $65 million contract.20

As he had done with the White Sox, Belle played nice with the media at the start of his Orioles career, granting interviews, attending Baltimore’s Fan Fest during the 1999 winter, and signing autographs during spring training. But a slow start at the plate (a .200 batting average with one RBI) led him to announce on March 14, 1999, that “I’m done with you guys.” And just like that, three months of good will went right down the clubhouse drain.

He played two years in Baltimore before an arthritic right hip condition forced him to retire on March 11, 2001. He was productive up until the end, averaging 30 home runs and 110 RBIs per Oriole season.21

Belle considered RBIs the most important offensive statistic in the game: “Hitting for a high average is nice. So is hitting a ton of home runs. But driving in a run a game is awesome.”22

It’s too bad he did not think of media relations as highly. When his name first appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot in 2006, he received a minuscule 7.7 percent of the vote. Translated: 520 ballots were cast and Belle was recognized on just 40 of them. His second — and final — year on the ballot came in 2007 when he collected just 3.5 percent of the vote. Needing 5 percent to remain on the ballot, Belle was off his ticket to Cooperstown for good.23

Belle’s career average 162-game season compares favorably with those of others already in the Hall, including Willie Stargell, Hack Wilson, Harmon Killebrew, Tony Perez, and Jim Rice. So why was he bounced from the ballot after just two seasons?

“His numbers were good,” Paul Hoynes of the Cleveland Plain Dealer said. “I thought if he played one or two more years at a high level, I’d have to vote for him. But he didn’t. He was a bad guy. And what goes around comes around.

“It wasn’t just us. He would sit there and dare people to talk to him. He would abuse the clubhouse guy, the PR guy, everybody.”24

According to Teddy Greenstein of the Chicago Tribune, who covered Belle during the 1998 season, “He was even a menace to Sox employees. He once cursed out a broadcaster for having the gall to enter the trainer’s room to get an aspirin. And he belittled hitting instructor Von Joshua by forbidding him from discussing his (Belle’s) swing with reporters.”25

Belle mellowed, but only after he was retired. He visited the Indians training camps in 2012 and 2015. The father of three girls, he lives with his family near Phoenix.

In 2016, Belle was elected to the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame. Citing family commitments, he declined to attend the ceremony.

Belle never met a fastball he couldn’t crush or a writer he wouldn’t berate. He played by his own rules, answering to no one. Maybe that’s why one of the best players in Cleveland Indians history is not remembered fondly, but “frown-ly.”

Last revised: November 12, 2018

This biography was published in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Notes

1 Baltimore Sun, June 10, 2001.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Jim Engster, “Albert Belle, man of mystery and mastery,” Tiger Rag Magazine, February 9, 2015.

5 New York Post, October 2, 1991.

6 New York Post, September 25, 1993.

7 Sports Illustrated, June 24, 1991.

8 New York Times, April 11, 1999.

9 albertbelle.net/timeline.php.

10 Sports Illustrated, October 9, 1995.

11 Lorain [Ohio Morning Journal, January 14, 1996.

12 USA Today, February 6, 1996.

13 Lorain Morning Journal, January 14, 1996.

14 New York Times, March 1, 1996.

15 Lorain Morning Journal, January 14, 1996.

16 albertbelle.net/timeline.php.

17 Sport Magazine, May 1997.

18 The Plain Dealer (Cleveland), March 9, 1997.

19 Ibid.

20 albertbelle.net/timeline.php

21 Sport Magazine, May 1997.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24Boston Globe, January 16, 2006.

25Ibid.

Full Name

Albert Jojuan Belle

Born

August 25, 1966 at Shreveport, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.