Alonzo Perry

Alonzo Perry had a successful Negro League career primarily as a pitcher but also as a first baseman and outfielder, and even pitched in the last Negro League World Series. Although he had two brief stints in the minor leagues, he became a baseball star in Latin America while playing in the Dominican Republic and a superstar during his time in Mexico.

Alonzo Perry had a successful Negro League career primarily as a pitcher but also as a first baseman and outfielder, and even pitched in the last Negro League World Series. Although he had two brief stints in the minor leagues, he became a baseball star in Latin America while playing in the Dominican Republic and a superstar during his time in Mexico.

Alonzo Perry was born on April 14, 1923, in Birmingham, Alabama, to Homer Perry and Rosa Thomas. His middle name was Thomas.

At age 17, Perry entered the world of baseball, appearing on the Homestead Grays’ 1940 roster, though statistics for his performance that year are unavailable. His professional career continued in the Negro Southern League, where he played for the Atlanta Black Crackers in 1945 and the Chattanooga Choo Choos to start the 1946 season.1

Perry’s Negro League career took off later in 1946 when he returned to the Homestead Grays as a pitcher and posted a 2-2 won-lost record.2 After seven games, he left the ballclub after a dispute with the team owner over money he had won gambling, finishing the season with his hometown Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. He remained with the Black Barons through the 1950 season.3 Though he continued to pitch through 1949, the strapping 6-foot-3 Perry’s hitting ability led to his making his initial appearances as a first baseman in 1946; eventually he split his playing time between the mound, first base, and occasionally the outfield.

Perry had his best year to date in 1948, helping lead the Black Barons to the Negro League World Series for the first time since 1944. He won 10 of 12 decisions and batted .325 while playing almost daily. One of his teammates was a talented high-school student, Willie Mays, who was in the first of his three seasons with Birmingham. Because of Mays’s youth, he had a different teammate watch over him every night, and he couldn’t go anywhere without a chaperone. The exceptions were two players, Jimmie Newberry and Alonzo Perry, who could not be trusted with watching the young Mays. As the baseball protégé said in Say Hey, “No one knew what they would get into after a game. They liked the ladies and like their beer.”4

In what became the last the Negro League World Series, against the Homestead Grays, the only record of Perry playing was in Game Three, in which he was the Negro American League champions’ starting pitcher at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field. In Birmingham’s lone victory in the series, Perry had a strong performance, maintaining a 3-1 lead until the eighth inning, when he gave up two runs that tied the game. He was relieved by Bill Greason, who halted the Grays’ rally and scored the winning run in the bottom of the ninth inning on an RBI single by Mays.

The 1949 season was Perry’s last as a starting pitcher in the Negro Leagues and was also his best as he finished with a 12-4 record with a 3.45 ERA. He also continued to play first base and the outfield. Manager Piper Davis also used his versatile pitcher-first baseman as an assistant coach because of his ability to steal the opposing team’s signs.5 However, Perry did not finish the 1949 season in Birmingham; he was sold to the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland Oaks and had his first opportunity to prove himself in Organized Baseball at the Triple-A level. Black Barons owner Tom Hayes, who was selling off his top stars to fend off a financial crisis, received $5,000 for Perry.6

Perry had a short stay in Oakland, playing in only 12 games. The lanky pitcher-first baseman was used in much the same way as in Birmingham; he pitched in eight games, played two games at first base, and pinch-hit twice. On the mound, he made four starts, pitched a total of 33 innings, and lost his one decision. Because of wildness, his 4.91 ERA was much higher than it had been as a Black Baron. The new Oak allowed more hits, 34, than innings pitched while both walking and striking out 20, and unleashing four wild pitches. His lackluster performance may have been a preview of the arm trouble that he developed after the season and which ended his pitching career. Perry’s performance at the plate was not much better. In 15 at-bats, he managed only three hits (for a .200 batting average) and one RBI. The Oaks released him and he returned to the comfortable setting of Birmingham for the 1950 season.

After arm trouble ended his pitching career, Perry settled into being a full-time position player. He played primarily at first base but also strolled the outfield during the 1950 season, which was his last in the Negro Leagues. Playing in the field full-time suited him well; he displayed what became his forte: hitting. He batted.313 with 14 home runs and 64 RBIs. Perry was also named to the East-West All-Star Game, in which he started at first base and went 2-for-3.7 (Only the Negro American League remained after the collapse of the Negro National League after the 1948 season, but the league’s premier players continued to meet at Chicago’s Comiskey Park and the participants were selected from the Eastern and Western divisions of the 10-team league.)

In 1950 Perry also became tied to a story about the “discovery” of Willie Mays. Over the years several variants of a story developed in which the Giants sent scout Eddie Montague to look at Perry because they needed a first baseman for their farm system; in doing so, he allegedly discovered Mays and signed both players.8 However, James S. Hirsch’s 2010 biography, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, which was authorized by Mays, had a different version. Although Montague was going to see Perry, Boston Braves scout Bill Maughn, a native of Alabama, who was unable to sign Mays because his front office did not agree with his assessment, told Montague to forget Perry and to “sign a young Negro player … with a great arm.”9 Montague knew that Perry wasn’t his man and concentrated instead on getting Mays. He ended up signing both players; with the veteran being assigned to Triple A for the 1951 season.

History has revealed all such stories to be apocryphal. The facts are that Giants owner Horace Stoneham and Black Barons owner Tom Hayes had reached an agreement in which Hayes would sell Mays’s contract for $10,000, and Montague was dispatched to get Mays’s signature on a contract. Montague’s story about being in Birmingham solely to scout Perry was a smokescreen he used to prevent other scouts and teams from becoming savvy to the fact that the Giants already had Mays sewed up.10

Although Perry was originally designated to go to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast league for 1951, he was sold to the Syracuse Chiefs of the International League before the start of the season. At Syracuse he played in only nine games, going 5-for-18 (.278) with 3 RBIs before being released. The starting first baseman, Eddie Shokes, was hitting only .238 at the time, which made Perry’s release a head-scratcher. It is possible that a defensive collision at first base in mid-May, in which the Chiefs pitcher was injured and the baserunner eventually scored the winning run, played a role.11 In his short time with the team, Perry made history by becoming the first player to break the color line in Syracuse. Although Elston Howard was the first African-American to sign with the Chiefs, he went into the military and never played in Syracuse. Vic Power, who played the entire year with the team and faced the brunt of the abuse for being the first black Chief in 1951, was actually a dark-skinned Puerto Rican; thus, according to the Syracuse Herald Journal, the honor goes to Perry, who played in only nine games.12

Like many former Negro Leaguers before him, Perry found another place willing to sign him so he could continue to play baseball in 1951. He first joined the Brandon Greys of the Man-Dak League, a Canadian league that became a refuge for Negro League ballplayers from the late 1940s to the middle 1950s. Displaying the hitting and power that would become his trademark wherever he played, the tall first baseman made quite the impression in his May 29 debut, clouting a home run, double, and two singles, with two walks, driving in three runs, and helping lead the Greys to an 8-6 victory over Elmwood. In a June 15 home rout of Carman, Perry slammed a homer that cleared the center-field fence and the avenue beyond. It was believed to be the first clout to clear the ballpark since 1933.13 When he left the league after five weeks to play for more money in the Dominican Republic, he was hitting .389 with 28 hits, including five home runs. Perry also had two pitching appearances with no record.14

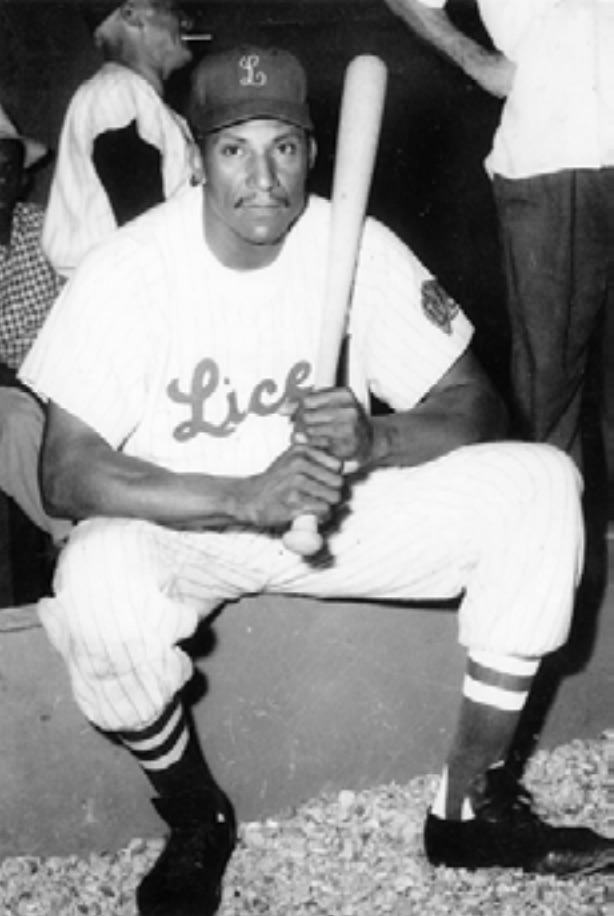

Perry’s decision to play for the Licey Tigers of the Dominican Summer League was a great one; he thrived in Latin America, where he soon became a superstar. Licey’s investment of a $1,500-per-month salary was quickly rewarded when Perry hit successfully in every game he played, a 25-game hitting streak that yielded a .400 average with 9 homers and 34 RBIs. His hot hitting carried over into the playoffs, and he delivered a hit in each of the seven games to stretch his streak to 32 games. He capped his 1951 season with a grand slam in the ninth inning of Game Seven to clinch the Summer League’s championship for the Tigers.

Perry led the Tigers to another championship in 1953, and the new hero continued performing for Licey through 1954, the Summer League’s last season before it converted to a winter league. For his four seasons with Licey, he batted .327 with a .592 slugging percentage while leading the league in home runs in 1951, 1952, and 1953; RBIs in 1952 and 1953; batting average in 1954; runs scored in 1954; and stolen bases in 1953.

Perry continued to play for Licey in the Winter League, starting with the 1954-55 season through 1958-59. The muscular slugger added another batting title (.332) in 1957-58 before finishing his Dominican career with the Estrellas Orientales in 1959-60. By the time he was through playing in the Dominican Republic, Perry held the league’s career slugging record, .489, the second highest Licey Tigers career batting average at .317, and the fourth highest batting average in Dominican League history at .310. He also set Licey’s career record with 45 home runs. The Tigers retired their star’s number 5, and Perry, who was nicknamed “Su Majestad” (His Majesty) by the Dominican fans, received the ultimate honor when he was inducted posthumously into the Dominican Republic Sports Hall of Fame in 1995 for his “great merits as a baseball player.”15

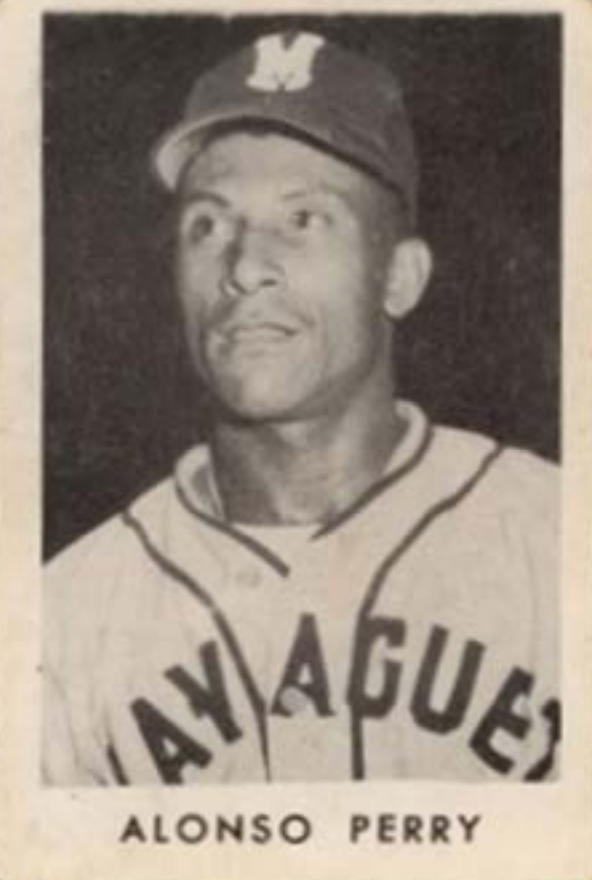

Winter ball was not new to Alonzo Perry when he joined Licey for the Dominican League’s inaugural 1955-56 season; he had already played four seasons in the Puerto Rican Winter League. Like many black ballplayers, making a living on the diamond year-round was better money than the alternatives offered by the segregated American society of that time. In Puerto Rico Perry joined Artie Wilson’s Mayagüez Indios, a team built around a core of Negro League players, which won the league’s championship in the 1948-49 season. Perry, who was still pitching at the time, played a key role in the rotation by throwing 11 complete games and posting an 11-4 won-lost record; in 18 games his ERA was a respectable 3.38. Adding to his value was the fact that he was also one of the team’s heavy hitters, belting nine home runs for a healthy .506 slugging percentage and knocking in 64 runs while batting .303.

Perry returned to Mayagüez in 1950-51. He could no longer pitch but had another solid year with the bat, hitting.333 with a .460 slugging percentage. In his last year with Mayagüez, 1951-52, he became the player-manager and continued to hit at a .323 clip, though his slugging percentage slipped to .442. Perry did not play winter ball in the following two years, but he returned to Puerto Rico with Ponce for the 1954-55 campaign after an opportunity to play for Martin Dihigo in the Mexican Winter League fell through. His season with Ponce turned out to be the worst of his career; he batted a meek .217 with only one homer while playing in 22 games.16

After the Dominican League changed to a winter format, Perry played summer ball in the Mexican League, where he had his greatest success and became a legend. In 1955, his first season with the Mexico City Red Devils, he thumped 21 homers and drove in 122 runs while batting .375, but he was just warming up. The 1956 season was the finest of his remarkable career as he led the Red Devils to the Mexican League championship and won the Triple Crown with 28 home runs, 118 RBIs, and a .392 batting average. As if that were not enough, he also topped the league in hits (177), doubles (33), triples (13), and runs scored (103).17 The club’s commanding record was 83-37 (a .692 winning percentage), and their first-year manager knew whom to credit for the successful season. The Sporting News wrote, “The domination of the Mexico City Reds in the pennant race south of the border represents a personal triumph for Manager Lazaro Salazar, who took over the club this season, but the Blue Prince would be the first to credit his success to the spectacular hitting of Alonzo Perry, the greatest slugger in the Mexican League since the days of the late Josh Gibson.”18 The comparison to the slugging prowess of Josh Gibson placed Alonzo Perry in the rarefied company of one of baseball’s greatest sluggers.

After the Dominican League changed to a winter format, Perry played summer ball in the Mexican League, where he had his greatest success and became a legend. In 1955, his first season with the Mexico City Red Devils, he thumped 21 homers and drove in 122 runs while batting .375, but he was just warming up. The 1956 season was the finest of his remarkable career as he led the Red Devils to the Mexican League championship and won the Triple Crown with 28 home runs, 118 RBIs, and a .392 batting average. As if that were not enough, he also topped the league in hits (177), doubles (33), triples (13), and runs scored (103).17 The club’s commanding record was 83-37 (a .692 winning percentage), and their first-year manager knew whom to credit for the successful season. The Sporting News wrote, “The domination of the Mexico City Reds in the pennant race south of the border represents a personal triumph for Manager Lazaro Salazar, who took over the club this season, but the Blue Prince would be the first to credit his success to the spectacular hitting of Alonzo Perry, the greatest slugger in the Mexican League since the days of the late Josh Gibson.”18 The comparison to the slugging prowess of Josh Gibson placed Alonzo Perry in the rarefied company of one of baseball’s greatest sluggers.

Perry’s Mexican moniker was “El Espiriton” (The Great or Honored One), and he continued to star with the Red Devils, leading the league in RBIs again in 1957. He retired after the 1959 season. During the last year in Mexico City, he suffered a broken finger that kept him out of the lineup for a time, but upon his return he resumed his power-hitting ways by punching four homers in two consecutive games.19 Although he was a superstar, he was not untouchable and had his 1959 Cadillac seized by customs officials for failure to take the car out of Mexico before the expiration of the permit that allowed him to bring it into the country.20 He finished the season with a .333 batting average that was second only to teammate Al Pinkston’s .369.21 Mexico City finished the regular season in third place, but the Red Devils won the playoffs and placed the largest number of players (five) on the postseason all-star team, including first baseman Alonzo Perry.22

After the season, Perry remained in Mexico to be the player-manager for the Puebla Sweet Potatoes of the Vera Cruz Winter League. The skipper’s only recorded pitching appearance after 1949 occurred in a Puebla game in 1959 in which three Puebla pitchers were shelled by the Cordoba Coffeemakers. Perry took the mound in the eighth inning with two runners on base and one out. He struck out the two hitters he faced to retire the side, then set down all three batters in order in the ninth to preserve a 9-7 victory.23 Late in December, with the Sweet Potatoes in last place, sporting a 7-16 record, 9½ games off the pace, Perry stepped down as manager and was replaced by Luis Molinero. He found it difficult to both manage and play.24

The Mexican League was struggling financially, so the Mexico City Reds, in an effort to save money, dumped salaries by releasing Perry and several other players. Perry quit baseball and retired.25 However, it turned out that he was not yet done with Mexican League baseball after all. The Monterrey Sultanes brought him out of retirement for the 1962 championship run. El Espiriton had a successful comeback as he led Monterrey to a 77-53 record and the Mexican League title. In doing so, Perry led the League in RBIs (105) for the second time; he tied his rookie teammate, Hector Espino, on the last day of the season.26 The strong first baseman also batted .316 and smacked 14 home runs. He returned for a final season in 1963 and went out in style by hitting for a .353 average with 17 homers and 90 RBIs. After the season, he retired again at age 40, finishing his Mexican League career as one of its greatest hitters. As the player with the league’s second highest career batting average (.355), he had become a legend in Mexico. He concluded his career south of the border with 1,107 hits, 128 home runs, and a .589 slugging percentage.

Negro League historians Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz have speculated about why Perry never got an opportunity to play in the major leagues. First, he was making as much money playing south of the border as he would have earned in the major leagues. Second, playing in Latin America gave him status and celebrity without the racial discrimination he would have experienced in the United States; he did not have any issues with staying in the best hotels and eating at all restaurants. And finally, he may have fallen out of favor with Organized Baseball when he played in the Dominican League because it was considered an outlaw league.27 James Riley cited additional reasons, stating, “Some scouts indicated that he lacked ‘style’ but his temperament and off-field activities might have been the real reason he was not signed by a major-league ballclub. He was often in trouble with the law, both while playing ball and after he retired from the diamond, and may have spent some ‘hard time’ as a result of his illegal activities.”28

Away from baseball, Perry was married to Gladys Davis on March 21, 1942, in Birmingham. According to the marriage certificate, she was born in Phenix City, Alabama, on April 17, 1923, to Pastor Joe Davis and Viola Hawkins. Perry listed his birth year as 1922 on the license, thus adding a year to his age, perhaps in an effort to appear to be older than his bride. Alonzo and Gladys divorced in December 1951. Her obituary lists four children including Alonzo Jr. and Diane Perry Favors. Alonzo Perry Jr. followed in his father’s footsteps and played first base for the Birmingham Black Barons in 1962 and with the Black Barons and Philadelphia Stars in 1963 and 1964 when they were barnstorming teams. Although he was a good hitter, he was not his father’s equal. Junior, who was born on July 20, 1942, died at age 67 on September 23, 2009.

Perry died on October 13, 1982, at the age of 59. As Revel and Munoz have written, “When Alonzo Perry passed away … we lost one of the great black ballplayers of his era. Unfortunately most baseball fans in the United States never had the opportunity to see him play.”29

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to SABR member Bill Mortell of Maryland, whose knowledge of Ancestry.com and research skills have proven invaluable in helping find information on Alonzo Perry.

Notes

1 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, Forgotten Heroes Alonzo Perry, Center for Negro League Research, 2009, cnlbr.org.

2 Ibid.

3 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro League Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 620-621.

4 Willie Mays with Lou Sahadi, Say Hey – The Autobiography of Willie Mays (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 39.

5 Larry Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham: The South’s Greatest Negro League Team and Its Players (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009), 149.

6 Powell, 56.

7 Revel and Munoz.

8 Willie Mays with Lou Sahadi, Say Hey – The Autobiography of Willie Mays (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 44.

9 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010), 59-60.

10 John Klima, Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009), 248-55.

11 Cy Kritzer, “International League,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1951: 26.

12 Matt Michael, “Who Broke the Color Line for the Chiefs in 1951?,” Syracuse Herald Journal, February 6, 1997

13 attheplate.com/wcbl/1951.

14 Ibid. I used the statistics from attheplate.com because of the detail it had on Perry’s brief stay in Canada. But Revel and Munoz had a different batting average for Perry with him leading the league in hitting at .397 with 19 RBIs when he left. Like attheplate.com, they had him with five homers. It is possible the difference could be caused by what games they recorded or missed at the end of his stay before he left for the Dominican Republic.

15 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2007), 152

16 Revel and Munoz.

17 Riley, 620-621.

18 Miguel Calzadilla, “Mexican League,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1956: 39.

19 Roberto Hernandez, “Mexican League,” The Sporting News, July 29, 1959: 33.

20 Ibid.

21 Roberto Hernandez, “Mexican League,” The Sporting News, September 16, 1959: 33.

22 Roberto Hernandez, “Mexican League,” The Sporting News, October 21, 1959: 21.

23 Roberto Hernandez, “Mexican League,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1959: 22

24 Roberto Hernandez, “Mexican League,” The Sporting News, December 30, 1959: 25.

25 Johnny Janes, “Don’t Quote Me,” San Antonio Express, April 22, 1960: 1-B.

26 The Sporting News, August 25, 1962: 39.

27 Ibid.

28 Riley, 620-621.

29 Revel and Munoz.

Full Name

Alonzo Thomas Perry

Born

April 14, 1923 at Birmingham, AL (US)

Died

October 13, 1982 at Birmingham, AL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.