Billy Grabarkewitz

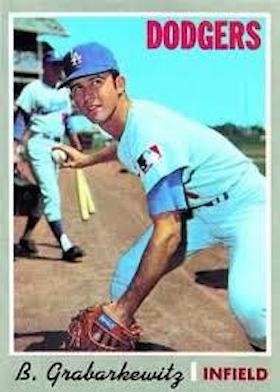

A master of the one-liner, Billy Grabarkewitz once claimed that “Abner Doubleday dreamed up this game [of baseball] to drive people crazy.”1 Perhaps no one knew this more than the diminutive right-handed hitting infielder whose entire career pivoted on injuries. It was injuries that slowed Grabarkewitz’s march to the big leagues; injury to fellow infielder and close friend Ted Sizemore in 1970 that opened the door to the majors; and injury that closed that same door a year later, relegating him to a utility role throughout the remainder of his seven-year major- league career.

A master of the one-liner, Billy Grabarkewitz once claimed that “Abner Doubleday dreamed up this game [of baseball] to drive people crazy.”1 Perhaps no one knew this more than the diminutive right-handed hitting infielder whose entire career pivoted on injuries. It was injuries that slowed Grabarkewitz’s march to the big leagues; injury to fellow infielder and close friend Ted Sizemore in 1970 that opened the door to the majors; and injury that closed that same door a year later, relegating him to a utility role throughout the remainder of his seven-year major- league career.

Billy Cordell Grabarkewitz was born on January 18, 1946, the second of three children of Adolph Charlie and Helen Maybelle (Bolton) Grabarkewitz, in Lockhart, Texas, 30 miles south of Austin. Of Irish descent on his mother’s side, his paternal grandparents were Polish immigrants who arrived in central Texas in the latter half of the 19th century. As a child Billy’s father worked as a grocery delivery boy to help his family during the Depression. Years later Adolph worked in sales and tended bar. He was also a big baseball fan. One of Billy’s childhood memories was watching the televised broadcast of the 1956 World Series with his father. Billy’s favorite player was Brooklyn shortstop Pee Wee Reese and in 1969 he became the first Dodger to wear the Hall of Famer’s uniform number 1. The following year former ace Don Newcombe compared Billy’s aggressive style of play to The Little Colonel.

At some point during Billy’s youth, his family relocated from Lockhart 60 miles southwest to San Antonio, where he went to Alamo Heights High School2 in the incorporated city of the same name. Grabarkewitz was an outstanding athlete lettering in baseball, basketball, football, golf and track. Following his graduation in 1964, Grabarkewitz went to St. Mary’s University3 in San Antonio, where he played third base for the Rattlers. Two years later he was selected by the Dodgers in the 12th round of the June amateur draft between Sizemore and future All Star shortstop Bill Russell.

Grabarkewitz was assigned to the Tri-City (Pasco, Washington) Atoms in the Northwest League where his first professional manager was another boyhood hero, Duke Snider. His transition to the Short-Season A circuit was seamless as Grabarkewitz, who was moved to second base, collected 20 hits in his first 53 at-bats. Though unable to maintain this .377 pace, the All Star infielder helped the Atoms to a first-place finish with league-leading marks in runs scored (62), stolen bases (21), walks (87) and OBP (.449) while finishing tied for third in home runs with 11.

In 1967, Grabarkewitz was promoted to the Santa Barbara Dodgers in the California League (Class A) where he continued his offensive onslaught as the club’s shortstop. For a second straight season he led his circuit in runs, stolen bases, walks and OBP while again finishing tied for third in homers to garner his second consecutive All Star berth. On Sunday, July 2, he connected for a ninth-inning game-winning grand slam against the Fresno Giants. It was one of 14 dingers Grabarkewitz collected on a Sunday (he had 24 homers for the season), a precursor to the “Billy Sunday” nickname he earned in the majors three years later. He finished the year in the Arizona Instructional League.

A “stellar shortstop . . . [r]egarded as the top prospect in the Los Angeles farm system,”4 in 1968 Grabarkewitz was promoted to AA Albuquerque in the Texas League. A broken finger from a bad-hop grounder did little to slow the youngster in the early weeks of the season, but not so the wrist fracture from a May 24 HBP that sidelined him for five weeks. Grabarkewitz rebounded with a three-homer day against the Amarillo Giants shortly after his return. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Dodgers—never an offensive stalwart throughout the 1960s—were en route to a league-worst 470 runs scored in 1968, a meager yield that garnered little support from veteran shortstop Zoilo Versalles’s scant offense (.196/.244/.266 line. Grabarkewitz appeared destined for Los Angeles. But on August 3, hours after being named to the circuit’s All-Star squad, Grabarkewitz broke his right ankle in four places when his spikes got caught in the shin guard of Dallas-Fort Worth catcher Hal King during a play at the plate. His season over, Grabarkewitz’s spectacular .308/.455/.512 line in just 289 at-bats (including 10 homers, half of which were struck on a Sunday) earned him the 1968 Topps Chewing Gum All-West AA shortstop. The Dodgers protected Grabarkewitz in the October 14 expansion draft and, pending his healthy return, anointed him the club’s starting shortstop for the 1969 season. “Grabarkewitz would have been the No. 1 player in the expansion draft if we had exposed him,” said Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley. “He has all the credentials, but what are credentials worth on crutches?”5

Though the crutches were gone the following spring Grabarkewitz was unable to mask a severe limp throughout spring training. Assigned to the AAA Spokane Indians in the Pacific Coast League, Grabarkewitz lashed out a .432 average in his first nine games. He was promptly recalled after the Dodgers placed pitcher John Purdin on the disabled list. On April 22, 1969, Grabarkewitz made his major-league debut in Dodger Stadium against the San Francisco Giants. Batting leadoff against veteran left-hander Ray Sadecki, the Dodgers shortstop grounded out third-to-first in the first, struck out in the second and finished 0-for-4. Moved to the lineup’s eighth spot the next day, Grabarkewitz collected his first major-league hit with an infield single in the eighth against Cincinnati Reds righty Wayne Granger. He also tied a major-league record by playing an entire nine-inning game at short without a single fielding chance.

The addition of Grabarkewitz to the Dodgers roster of rookies Sizemore, Russell, Alan Foster, Bill Sudakis and 22-year-old sophomore Willie Crawford prompted countless jokes about the players’ ability to get into the movies at half price. Dubbed “The Mod Squad” after the popular television program of the same name, the nickname seemed all the more appropriate due to the flashy clothes donned by each of them. But Grabarkewitz’ participation with the “Squad” was short-lived. Except for two extra-base hits and three RBIs against the Atlanta Braves on April 27, he struggled with a 3-for-39 run that eventually relegated him to mere pinch-running roles. He was reassigned to Spokane following the June 11 acquisition of veteran shortstop and former Dodgers great Maury Wills (another of Grabarkewitz’s many childhood heroes).

A month later Grabarkewitz returned to the club to spell Jim Lefebvre while the veteran infielder met his obligation in the Army Reserve. He stayed with the Dodgers throughout the remainder of the season. Used sparingly, Grabarkewitz garnered just 15 at-bats without collecting a hit. Despite the limited exposure, he remained much sought after by the other major-league clubs. In August the Dodgers, immersed in a tight pennant race in the newly formed Western Division, hoped to bolster their bullpen by acquiring future HOF righty Hoyt Wilhelm from the crosstown California Angels. When the Angels asked for Grabarkewitz, the Dodgers quickly walked away. During the winter, as the organization experimented with him behind the plate in the Arizona Instructional League, the Dodgers were inundated with offers for Grabarkewitz from nearly every direction, including the Montreal Expos, San Diego Padres, Kansas City Royals and both New York clubs. “Billy is one of the real valuable type players,” Spokane manager and future HOF inductee Tom Lasorda explained. “He can do it all. He can play third, short or second with equal skill . . . Billy also is a fine offensive player.”6

In 1970, despite a strong grapefruit league campaign, Grabarkewitz was elbowed to the bench by the emergence of another close friend, 21-year-old third baseman Steve Garvey. But five games into the season Sizemore, the club’s second baseman, went down with a leg injury. Though the injury was not severe—he missed only six starts—Grabrakewitz made the most of the opportunity before him. On April 12—a Sunday—he connected for his first major-league home run (the club’s first of the season), a two-run drive against righty Gary Ross in a 6-0 win over the Padres. Two days later Grabarkewitz’s seventh-inning RBI single proved the winning margin in a 3-2 win against the Houston Astros. When Sizemore returned to the field on April 19, Grabarkewitz was moved to third as Garvey struggled with an .048 average. Except for an 0-for-4 run against future HOF greats Nolan Ryan and Tom Seaver, he finished the month with a .429 average. (He was hit by a Ryan fastball that he later claimed left an “imprint . . . [that] was still on my left shoulder Christmas Day.”7)

On May 3 (another Sunday), Grabarkewitz continued his assault of NL pitchers with three hits and five RBIs against the Expos. Asked by reporters about “the last time he had five,” he cracked, ‘I think it was No. 3 at Lakeside Country Club.’”8 Three weeks later Grabarkewitz scored five runs and came within a homer of the cycle to lead his club to a 19-3 win over the Giants. On May 31 (Sunday), his two-run single in the seventh helped the Dodgers overcome a 6-1 deficit against St. Louis, and his eleventh-inning two-run homer sent the Cardinals to an 8-6 defeat. The next day Grabarkewitz struck another game-winning two run homer, this time against the Chicago Cubs. Yet another game-winning blow came two weeks later against Pittsburgh in a 1-0 squeaker.

Leading the league in consonants, Grabarkewitz briefly held the NL batting crown while his eye-popping .394/.479/.564 line in May earned runner-up consideration for Player of the Month (second to the sizzling .770 slugging percentage posted by Braves slugger Rico Carty). His surprising surge left MLB officials flatfooted when All-Star ballots were issued without his name and a vigorous write-in campaign ensued. He was unable to overcome the popular vote of future HOF third baseman Tony Perez, but Mets skipper Gil Hodges selected Grabarkewitz as a reserve. Replacing Perez in the seventh, he lined a single to left in the 12th to set up the legendary Pete Rose–Ray Fosse collision that gave the NL a 5-4 win.

On July 1, in the one thousandth game as a Los Angeles-based club, the Dodgers were led by another Grabarkewitz near-cycle (this time a triple shy) as his three RBIs paced a 6-3 win against Houston. One week later they defeated the Astros again when his ninth-inning RBI single proved the decisive margin in a 6-5 win, followed by Grabarkewitz’s game-winning homer against the Mets on July 16. The nickname “Billy Sunday” surfaced around this time as he posted a .392-3-17 line in the first 14 Sundays, during which the club went 11-3. In August Grabarkewitz, Manny Mota, Willie Davis and Wes Parker were each sporting a .300 average—the first time the club had a quartet of .300 hitters since their days in Brooklyn. Perhaps more important, Grabarkewitz seemingly had locked down the Dodgers’ third base job, a position that had seen 39 hopefuls since the club had moved to Los Angeles in 1958. Always ready with an entertaining quote, Grabarkewitz became a favorite of sportswriters in every major league city. Meanwhile, the San Antonio Light took advantage of their hometown connection by scripting him to a sports column in their daily newspaper.

But Grabarkewitz began showing signs of slippage when he finished July with just 11 hits in 52 at-bats. He struck out 91 times in the first half of the season and the Dodgers, attempting to curb this weakness, began tweaking his aggressive approach by getting him to hit to right field. Though the strikeouts lessened, so did the hitting—.173 in August. Despite finishing among the club leaders in nearly every offensive category—including a team-best 17 homers—he also set a franchise record of 149 strikeouts. After the season Grabarkewitz returned to the Arizona Instructional League to work on his swing and, following the trade of Sizemore to the Cardinals, continue his grooming at second base, where he had finished the season.

Though MLB officials added his name to the All-Star ballot in 1971 (and again in 1972) Grabarkewitz never came close to selection to the Mid-Summer Classic again. On the second day of spring training 1971, following a full workout, Dodgers vice-president Al Campanis entered the clubhouse and instructed Grabarkewitz and prospect Marv Galliher to return to the field for double play practice. The additional session lasted over an hour and strained both players’ arms. Before the year was out, they both underwent surgery.

Grabarkewitz did not make his first start until two weeks into the season, contributing an eighth- inning game-winning two-run double for a 3-2 win against the Padres. Used sparingly at first, he bounced back in May with a 9-for-20 run. Seemingly restored to full health, he was the object of an aggressive trade query from the Mets. But events took a turn for the worse on May 16 when, in the second inning of a game against the Giants, Grabarkewitz was removed with an ailing shoulder and assigned to the disabled list. Team doctor Frank Jobe initially ruled out surgery before a second stint on the disabled list, followed by continued offseason pain, forced a December operation. After garnering just 71 at-bats for the season, Grabarkewitz was still able to view the situation comically: “I was told that if I cut down on my strikeouts, I’d get a big raise. You can’t strike out when you don’t play.”9

In the 1972 spring training, Grabarkewitz competed with Garvey and 24-year-old prospect Ron Cey for the third base job. This marked the first year in which the franchise put players’ names on uniforms, a matter that gave Grabarkewitz a sense of security: “If the Dodgers go to the expense of putting my name on the back of a uniform, I know darn well they aren’t going to trade me,” he cracked.10 11 But if the club was not prepared to trade him, nor was it prepared to play him when, following an 0-for-7 start to the season, Grabarkewitz was relegated to a utility role. “I have so many splinters from sitting on the bench that if somebody struck a match, I might catch fire,” he joked.12 Grabarkewitz garnered just 144 at-bats for the season with a dismal .167/.265/.278 line. Both injuries and bad luck played a part, such as the starting assignment Grabarkewitz garnered on August 20 after returning from a fractured finger. In his first at-bat he was hit in the head by Cubs righty Rick Reuschel and missed 14 additional games.

Grabarkewitz was playing winter ball for Lasorda with the Dominican League’s Tigres del Licey when he was traded with future HOF outfielder Frank Robinson and prospect Bobby Valentine to the California Angels on November 28 for pitcher Andy Messersmith in a seven-player swap. Initially projected to compete with Valentine at shortstop (both were eventually pushed aside by 22-year-old rookie Rudy Meoli), Grabarkewitz was given a short leash at third before being consigned to the bench. On May 31, 1973, he connected for a two-run homer against southpaw John Curtis to ignite the Angels’ 7-6 comeback win over the Boston Red Sox, but this was immediately followed by a 1-for-24 slump. “I hate the thought of being a utility player,”13 Grabarkewitz had said three years before, but this was precisely the role entrusted to him, a role that included his major-league debut in the outfield on June 23. After garnering just one starting assignment over an 18-day span, he was acquired by the Philadelphia Phillies on waivers on August 14.

Seeking a boost from any quarter, the last-place Phillies put Grabarkewitz at second base. He rebounded with a .288/.397/.409 line in 66 at-bats. With the possibility of winning the starting job from incumbent second baseman Denny Doyle, a rejuvenated career beckoned to Grabarkewitz in the City of Brotherly Love. “I found a nice part of Philadelphia to live in,” he claimed. “It’s called New Jersey.”14 After the season Grabarkewitz accompanied future HOF third baseman Mike Schmidt and other Phillies teammates south to play in the Puerto Rican Winter League.

But Grabarkewitz’s hopes of capturing the Phillies second base job were quickly dashed with the club’s offseason acquisition of Dave Cash from the Pittsburgh Pirates. Except for one appearance at third base as a defensive replacement, Grabarkewitz spent the first third of the 1974 season merely in pinch-hitting or pinch-running roles. On July 10 he was purchased by the last-place Cubs. Chicago entered the season with a platoon of two 24-year-old second basemen who yielded a combined .198-0-21 line for the year (a situation that was enhanced little by the promotion of yet two more 24-year-olds). With the exception of a July 27 game against the Cardinals in which Grabarkewitz committed three errors, the generally sure-handed fielder—who was only four years older than his competition—provided a measure of stability to the club both in the field and at the plate. But the Cubs’ offseason acquisition of Manny Trillo made Grabarkewitz expendable and the following spring he was released.

In 1975 Grabarkewitz signed with the Oakland Athletics. On April 25 he made his sixth appearance—and second at-bat—of the season pinch-hitting for second baseman Phil Garner. Grabarkewitz struck out looking. It proved to be his last appearance in the major leagues. Three days later he was assigned to the Tucson Toros in the PCL to make room for Matt Alexander, acquired from the Cubs. As a five-year player Grabarkewitz could not be assigned without written permission. He filed a grievance with the players’ union but nothing came of this. He finished the season in Tucson and retired.

Grabarkewitz had married Mary Ann Kennedy in Bexar County, Texas, on April 9, 1967. They had two sons. Referring to the many stops along his seven-year major league career, he once wrote a postcard to Mary Ann from Chicago saying, “By the time you know where I am, I probably won’t be there.”15 Billy joined his family in Texas, but he and Mary Ann divorced in 1976. Nearly 20 years later he tried marriage again, this time with Laurie A. Morazzano in 1994 in Tarrant County, Texas (where he had established a successful insurance venture). One year later this union produced one daughter.

A beloved teammate because of his wit, Grabarkewitz was remembered on a number of fronts. In the early 1970s he joined fellow Dodger teammates Claude Osteen and Jeff Torborg as youth instructors at baseball camps at the University of Redlands (60 miles east of Los Angeles). A decade later Grabarkewitz was inducted into the St. Mary’s University’s Athletic Hall of Fame.

But most of the memories surrounding Grabarkewitz stem from his nickname “Gabby”. He surfaced in the majors just five years after the notable Free Speech Movement and appears to have taken the campaign’s crusade to heart. Ready with a quote or a quick crack, Grabarkewitz was a favorite among both sportswriters and the rubber chicken circuit. During the 1973 spring training Angels manager Bobby Winkles joked that “Don Sutton warned me I would have to keep [Grabarkewitz] in the shade the first couple of workouts or his tongue would get sunburned.”16 Taking this jest in stride, Grabarkewitz retorted, “I was so tired last night I fell asleep in mid-sentence.”17

Alluding to the many injuries he sustained in his career, Grabarkewitz is perhaps best remembered for the crack, “I’ve been X-rayed so much I glow in the dark.”18 But jokes aside, it was injuries that eventually sidelined Grabarkewitz’s once-bright potential. He concluded a seven-year major-league career with a .236/.351/.364 line with 28 home runs and 141 RBIs in 1,161 at-bats.

Last revised: August 25, 2016

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank SABR member Bill Mortell for his valuable research.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Notes

1 “Willie D. Right on Schedule—Second-Half Swat Spree,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1970: 15.

2 Future major league infielder and manager Davey Johnson attended the same school, graduating approximately three years before Grabarkewitz.

3 Several sources also reflect Texas State University which the author was unable to confirm.

4 “Grabarkewitz Sustains Compound Leg Fracture,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1968: 35.

5 “Dodgers Hand Shortstop to Grabarkewitz,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1968: 41.

6 “Grabby Boosts Dodger Infield Insurance,” The Sporting News, January 17, 1970: 38.

7 “Insiders Say,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1973: 6.

8 “Billy G. Is Just Great, Dodgers Crow,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1970: 3.

9 “Ross Newhan column,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1971: 13.

10 “Ross Newhan column,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1972: 32.

11 Another nickname Grabarkewitz earned during his playing career was “Billy Gee Whiz” from the abbreviated “G’w’z” that often appeared in the box scores.

12 “Ross Newhan column,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1972: 24.

13 “Grabby Leave Bench to Give Dodgers a Hand,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1970: 10.

14 “Joe Ferguson Explodes His Theory on Mental Fatigue,” The Sporting News, September 15, 1973: 13.

15 “Ross Newhan column,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1974: 16.

16 “Valentine Losing His Heart to Angels,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1973: 44.

17 “Angels Watch F. Robby Earn ‘Old Pro’ Label,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1973: 25.

18 “Dodgers Hand Shortstop to Grabarkewitz,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1968: 41.

Full Name

Billy Cordell Grabarkewitz

Born

January 18, 1946 at Lockhart, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.