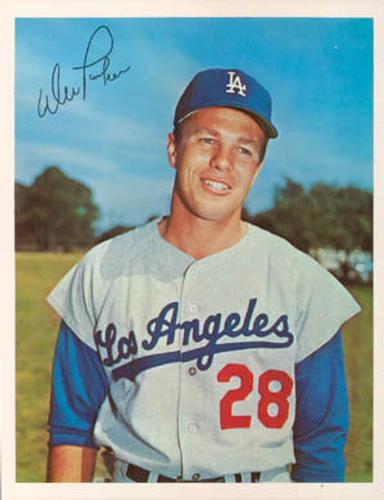

Wes Parker

In a city fueled by flash, Wes Parker was anything but.

In a city fueled by flash, Wes Parker was anything but.

A child of southern California privilege, Parker grew up in Brentwood with a private school education, material needs met, and natural athletic ability in several sports besides baseball. Money, though it bestowed abundant opportunity, did not generate airs, snobbery, or a feeling of entitlement in him. They were shunned in the Parker household, where the raison d´être was the pursuit of excellence based upon decorum and learning.

Scribes attributed the accoutrements of wealth to Parker, as if his biggest worry was whether to buy a black Cadillac or a gray one. These perceptions were sarcastic at best and slanderous at worst towards the Dodger who set a defensive standard for NL first baseman, receiving six consecutive Gold Glove Awards in a nine-year career. Los Angeles Times sportswriter Jim Murray skewered Parker’s upbringing. “No wonder the Dodgers didn’t give him a bonus when he showed up. They thought he would run for it as soon as he found out dressing rooms didn’t have governesses. Wes didn’t even spit,” wrote Murray in a 1969 column.1 Another time, he observed, “Wes Parker’s neighbors were not sharecroppers, janitors or a collection of big city tap-outs. Gary Cooper lived right up the street. So did Cesar Romero, Fred MacMurray and a bank president or two. When Wes played ball in the backyard he broke some of the most famous windows in Hollywood.”2

But he could not ignore Parker’s prowess at first base: “Wes Parker was one of the most graceful athletes ever to play the game,” he said. “Watching him field a ball was like watching Nureyev dance. Whatever the mysterious quality called ‘coordination’ was he had more of it than the kids from the other side of the tracks.” 3

Born on November 13, 1939, Maurice Wesley Parker III is a middle child sandwiched between younger brother Lyn and older sister Celia. Parker’s father, a native of the Boston area—Cohasset, to be precise—sold casualty insurance; on a vacation in Chicago, he met his future wife, Mary Joslyn, whose father had a winter home in Bel Air, one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in the country. The Joslyns lived in Hinsdale, a Chicago suburb.

Hating the insurance business prompted a career change—a business opportunity in Santa Monica came first, then a leadership position at a manufacturing company making bomb parts during World War II. After the war, the company shifted to making steel kitchen cabinets. Maurice vaulted from running the company to taking it over: the name changed to Parker Manufacturing Company.4 He also ventured into industrial real estate, another lucrative endeavor.5

A Little League coach named Ned Bowler was the first to affirm Parker’s baseball skills. “I was only [11] at the time, and he helped mold my approach to baseball. He emphasized the importance of giving your best and minimizing the importance of victory.” It was invaluable for a youngster on a journey that took him to the major leagues. Meanwhile, Charlie Dressen, a Dodgers scout and friend of Parker’s father, kept tabs through high school and college. Dressen had managed the team in the early 1950s, when it called Brooklyn home. 6

“I played intramural sports but didn’t go out for teams at first,” tells Parker. “At Harvard Military Academy, which is now Harvard Westlake, I played intramural basketball, football, and track. I also played on Harvard’s baseball team. Football was my second favorite sport. I played safety and quarterback in college.”7

Parker earned an Olympic League MVP Award for his gridiron exploits at Harvard. His C average triggered rejections from UCLA and USC. At Claremont Men’s College—now Claremont McKenna College—about 50 miles east of Los Angeles, Parker made small college All-American in his junior year. He later transferred to USC, graduating with a B.A. in history in 1962.8

During his college years, Parker had pondered a career in medicine. “It was the summer and I took a job as an orderly at Santa Monica Hospital,” explained Parker from a hospital bed at Chicago’s Wesley Memorial Hospital during the 1969 season as he recovered from an appendectomy. “I thought I might want to be a doctor, but I found I didn’t have the dedication.”9

A summer trip to Europe gave Parker the chance to clear his head, weigh his options, and decide on baseball as a career. In his Paris hotel room, he thought it over. “The way I saw it, I had three choices—(1) work for my father; (2) have my father help me get a job with a company like Carnation or selling stock; or (3) go home and really try and make it as a baseball player. I sincerely loved baseball, and so the choice was really easy.”

Parker reached out to Dressen and, whether out of loyalty to the elder Parker or an instinct based on the aspiring ballplayer’s rejecting offers from major league teams in favor of going to college—or both—Dressen agreed to help, getting him a spot on a Dodgers rookie team playing around Los Angeles in a semi-pro league. “If you look good, well—it can mean a ticket to spring training at Vero Beach,” he promised.10

Parker looked good, indeed. In December 1962, he signed with the Dodgers organization. After working out at Vero Beach in spring training for the 1963 season, he got shipped to the Santa Barbara Dodgers in the Class A California League and then the Albuquerque Dukes in the Double-A Texas League. His playing time consisted of 92 games in Santa Barbara, where he hit .305 and 26 in Albuquerque where he hit .350 and a league-leading .357 during a return stint in the Instructional League. 11

After the Dodgers swept the New York Yankees in the 1963 World Series, Buzzie Bavasi, LA’s legendary general manager, bought Parker’s contract from the Spokane Indians—the club’s Triple-A Pacific Coast League team. This put Parker on the 40-man roster, making him eligible for spring training and selection to the 25-man roster for the regular season. Being a Dodger fulfilled a fantasy for the kid from Brentwood, who grew up rooting for the Hollywood Stars, but shifted allegiances when the Stars relocated to Salt Lake City after the Dodgers arrived in 1958. “I went to all the Opening Days!” exclaims Parker.

While America’s teenage girls swooned over the Beatles’ American début on The Ed Sullivan Show and teenage boys copied their haircuts, the hometown rookie prepared for a potential début with the Dodgers. After what he describes as a “phenomenal Spring Training in 1964,” Parker joined the starting lineup of the newly crowned World Series champions; his rookie season ended with 124 games played, and a .257/.303/.341 slash line.12

Initially switching between right field and first base, Parker evolved into a defensive master at first, though he did appreciate the outfield as well. “I like it because I like to run. I get as big a thrill out of taking a hit away from someone, as I do getting one myself,” explained Parker. Making the league minimum—$7,000—with no bonus attached, Parker was a bargain not seen since Walter O’Malley got Chavez Ravine as a gift from Los Angeles politicos to build Dodger Stadium.13

In 1965, the fan-turned-major leaguer played in 154 games, batted .238, and had an on-base percentage of .334. Before facing the Minnesota Twins in the World Series, Parker questioned his ability and answered his doubts during Game 4. “I was so concerned that I wouldn’t be as good as the other guys who won two years earlier. I was thrilled when we won because it validated the fact that I could play,” reveals Parker, who reached first base on a bunt in the bottom of the second inning, stole second base, moved to third on a wild pitch by Mudcat Grant, and scored on a John Roseboro single. Parker bashed a home run later in the 7-2 Dodger victory; he hit .304 for the series, which the Dodgers won in seven games—he played in all seven.14

A couple of weeks after the World Series ended, Parker headed to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota for allergy tests and X-rays of a shoulder dislocated “in a collision at home plate” during a Dodgers-Reds game in Cincinnati. The visit not only revealed Parker’s vulnerability to allergies, but also his vigor in recovering from an injury. “My health is excellent although I checked out to be allergic to a great number of weeds, grasses and various dusts,” reported Parker. “My shoulder has healed perfectly, and the doctors advised that I work out with weights to strengthen it. When I get home I’m going to begin the weightlifting program.”15

When the 1966 season began, Parker had added about 10 pounds to his physique. An enhanced diet included “a protein supplement and a quart of milk to pile on an extra 1,800 calories each day. “I not only feel stronger physically, but this added weight has built me up mentally as well,” said Parker. “If you don’t feel strong at the plate you don’t have the confidence or feel aggressive enough.”16 Parker’s changes, physical and mental, were evident. In 1966, he played in 156 games, batted .253, and lifted his OBP to .351. The Dodgers returned to the World Series and dropped four straight to the Baltimore Orioles. Parker batted .231—two of his three hits were doubles; he struck out three times and drew one walk.

“We were really a mature team,” says Parker of the 1960s Dodgers. “Not just off the field but particularly on the field and at crunch time. I never saw guys who were so focused on finding ways to win games. It was a professional and superb team that never let up. I learned that from my teammates. The Dodgers had 20 years of winning seasons, from 1947 to 1966—Jackie Robinson’s first year to Sandy Koufax’s last year. If they weren’t winning a World Series, they were winning a pennant, or almost winning one. I never saw anything like it. I’m blessed because I wouldn’t have understood if someone had to explain it to me.

“The Dodgers had a reputation for winning that came from Brooklyn. I don’t think that they would have achieved the notoriety had they not won in their first years in Los Angeles. The Lakers came from Minneapolis, but they have a national brand because people remember that they won here. Once you win, you carry a level of interest. This was enhanced by the Dodgers winning the World Series in 1959, the team’s second year in L.A. It followed a season when they finished next to last. In 1962, they lost a three-game playoff to the Giants. Then in 1963, they beat the Yankees.”17

Joining a team with a pedigree of excellence influenced Parker to strive for improvement, wherever he perceived it. Psycho-Cybernetics, a strategy of positive thinking, was a touchstone that allowed him to squash the fears that he felt early in his career.18

Disappointed by his performance against the Orioles, Parker sought the scrutiny of former Dodger slugger Duke Snider during spring training in 1967. “I love the guy, but he’s just too nice and friendly on the field for his own good,” said the iconic centerfielder of Parker’s easygoing manner. “We’ve got to make an animal of Wes at the plate. He shouldn’t go to the plate and exchange pleasantries with the catcher. He should go up there and tell the guy to go to hell.”19

Though Parker did not carry himself like Ty Cobb or Pete Rose, his inner determination to win was no less fiery. Maintaining his offensive output in 1967, Parker ended the season with a batting average of .247, just a few points below his 1966 average. In both seasons, he had 83 strikeouts. 1967 was a landmark year for Parker—he won the first of six consecutive Gold Glove Awards. “Gil Hodges gave me some tips when I started with the Dodgers. He told me not to switch feet when I caught a ball, just use my left foot,” says Parker.20

Though his batting average slipped to .239 in 1968, Parker’s defense was as exemplary as a flawless diamond. During a road trip, the official scorer during a game against the Houston Astros ruled a ground ball that got past Parker as an error. “The people who were there said that it should have been called a hit, that it took a crazy bounce off the Astroturf and skittered over Parker’s head,” wrote John Wiebusch in the Los Angeles Times. That single error prevented Parker from having an error-free season.

As the Dodgers prepared to face new teams in the expansion year of 1969—the Montreal Expos and San Diego Padres—Parker remained indefatigable in trying to bolster his hitting game. “No one knows my weaknesses more than I and I’m working this spring as hard as I can to correct that,” said the defensive star during spring training. His dedication paid off. A couple of weeks into the season, he topped the Dodgers in batting average, hits, runs, home runs, and RBI. Parker, a switch-hitter, credited hitting coach and former Dodger star Dixie Walker with his improvement. Admitting that he “had little confidence in my ability to swing the bat left-handed and the times when I was relaxed, really relaxed, were all too infrequent,” Parker emphasized, “Dixie has brought confidence and relaxation to me.” Because Parker didn’t have a lot of power—64 career home runs—Walker admonished to swing down and try to hit ground balls and line drives.21

When the season ended, Parker had boosted his batting average to .278, nearly 40 points higher. His on-base percentage rose from .312 to .353. In the first half of season, before the appendectomy, Parker averaged .296 with 51 RBI. Forced onto the DL for 20 games diminished offensive opportunities; he wound up with 68 RBI for the season.

In 1970, Parker had what he labeled “the biggest thrill I’ve ever had in baseball”—he hit for the cycle in a game against the World Series champion New York Mets. “I feel that this is the climax of a seven-year struggle to arrive as a major league hitter. I feel that tonight I took the final step,” said Parker after he tripled home two bonus runs in the top of 10th inning to give the Dodgers a 7-4 victory. He had almost accomplished the feat two years earlier in a game against the Reds when he crushed a ball toward the right field stands, but Lee May “leaped and caught [it] in front of the low fence.”22

Parker played in 161 games in 1970, leading the major leagues with 47 doubles, notching 111 RBI, and compiling 196 hits for a .319 batting average—the fifth highest average in the National League. It was Parker’s only .300 season. When he received a reported boost in his contract from $50,000 to $75,000, he acknowledged, “The thing is, though, that the money is still frosting. The satisfaction from last year is that I proved I could do what I always felt I could do.” His team agreed, awarding him its Most Valuable Player Award.23

As the Dodgers’ player representative in the early 1970s, Parker considered the impact of rising salaries, believed that greed could ignite a destructive backlash against players in the upper echelon, and predicted a $200,000 salary ceiling. “If I were an owner,” he declared, “I’d take high salaries to a point and then say the hell with it. I’d trade off or just get rid of the high salaried players.”24

With a view that bargaining could do more harm than good, Parker queried, “Don’t you think labor unions are hurting this country?” Jim Murray responded with another retort aimed at Parker’s refined upbringing: “Which proves, you can take the boy out of stocks and bonds. But can you take the stocks and bonds out of the boy?”25

Parker’s contributions to the 1971 Dodgers fell off a bit from his outstanding 1970 numbers, but remained solid: a .274 batting average, 157 games, 146 hits, 24 doubles, 62 RBI. At the beginning of the 1972 season, MLB players went on a short-lived strike. Parker’s position favored neither his peers nor his bosses. He refused to vote on the strike at all, thereby igniting a call for him to resign as the Dodgers player representative.26 The tally for the strike vote on team was 47-0.27

In 1972, Parker saw less playing time—130 games. He ended the season with 119 hits, .279 batting average, 14 doubles, and 62 RBI.

Two days before Thanksgiving—and just eight days after turning 33—Parker announced his retirement from baseball in a prepared statement:

This decision was not an easy one as it is hard to give up something that I love and have been doing all my life. My main reason for concluding my career is to allow myself time to enjoy the many interests which I have in life while I’m still young. The desire to lead a more settled life is another contributing factor. The time I have spent in baseball has been deeply satisfying to me. My first big league hit (in 1964), winning the World Series in 1965, winning my first Golden Glove, driving in 111 runs in 1970, and playing with Maury Wills, the greatest competitor I have ever known, are among my treasured memories.28

Parker, who showed no signs of deteriorating skills, finished his major league career with offensive statistics indicative of an everyday player with occasional moments of glory: 1,288 games played, 1,110 hits, 470 RBI; and a .267/.351/.375 slash line. He also achieved a career .996 fielding percentage—tied for 12th all-time among first-sackers as of 2017—and only 45 errors in 10,380 chances. Like Gil Hodges before him and Bill Buckner and Steve Garvey after him, Parker’s invaluable defensive play at first instilled confidence in the denizens of Dodger Stadium.

“By the time I retired, we had winning records, but we weren’t winning pennants. My friends were gone. Tommy Davis was traded. Maury Wills was released. Don Drysdale, Sandy Koufax, Wally Moon, and Jim Gilliam had retired. The game was changing. It was becoming more individualized. Plus, I got tired of the traveling.”29

Parker’s passion for baseball did not exclude other interests, an important factor in the decision to hang up the spikes. “To me, major-league baseball is a game for single men in the 20’s,” opined Parker upon his retirement. “It’s like being an airline stewardess. [If] you’re in it too long, you’re trapped. Baseball was fun for 10 years, but I had enough. I won’t be making as much money as I was. I don’t even have a job yet. But I’m not worried about that. The human values are more important.”30

Fans from Pasadena to Pomona and Corona to Compton often saw star power in the stands at Dodger home games. Hollywood glamour sprinkled across the stands at Chavez Ravine because celebrities would trade the sound stage spotlights for an afternoon of sunshine at the ballpark nestled in the San Gabriel Mountains. “Bob Cummings invited us to his home for a big party. Doris Day, Frank Sinatra, and Milton Berle came to a lot of games,” remembered Parker, who grew up among show business elite—his high school classmates included Doris Day’s kids and Gregory Peck’s sons.

“Playing in Dodger Stadium was tough for hitters. Pitchers loved it. The groundskeepers left the grass long in the infield and the outfield because they wanted balls to slow down and die,” reveals Parker. “It was the most beautiful ballpark, but I preferred to play at Sportsman’s Park, Wrigley Field, and Crosley Field.

“Walter Alston was a hands-off manager. He gave me the room to grow as a player and treated everyone like a man and didn’t micromanage or overmanage. The Dodgers were almost a self-managed team. I learned from my teammates, especially Moon, Wills, Drysdale, and Gilliam. They were determined to win.

“In the beginning of my career, I made a lot of mistakes, mostly a result of not thinking properly or being out of position. For instance, sliding head first into home plate is not a good idea because you can beat up your hands. Learning which pitches to swing at and when to swing at them are skills I learned from other players because Alston never tutored on those things. There was a self-disciplined quality on the Dodgers in the 1960s and early 1970s.”31

During Parker’s time with the Dodgers, a highly significant streak of counterculture pulsated in the country’s youth; hippies, Woodstock, and the implicit endorsement of marijuana became hallmarks of the Baby Boom generation. By contrast, Parker joined fellow Dodger Jim LeFebvre and L.A. disc jockey Dave Hull—all three professed never to have used drugs—to form Athletes for Youth, which got nationwide attention, including honors from President Richard Nixon. The trio spoke at schools to thousands of kids about the dangers for drug use. 32

Parker recounted a story from his teenage years that struck a familiar chord with students during one of his appearances. “So in my first year I came home with three D’s and two F’s. So my dad calls a family conference. You know about family conferences. You go into the den, the doors are closed. So my dad says, ‘Wes, these grades, we’ve got to do something. I’ll give you an alternative. Either you get these grades up or you go to work in a factory.’”

The next morning, father and son drove to the factory. It’s one thing to posit a scenario and quite another to see the tangibles of it. Parker’s grades improved. Another story illustrated the value of staying away from kids who had no boundaries—Parker’s father told him to get out of a car whenever he felt the driver was wild and call home to get picked up. Parker said it happened “two or three days later,” and the other kids in the car lauded him the next day for having the courage to get out.33

Parker took a broadcasting job with the Cincinnati Reds for the 1973 season. On December 14, the Dodgers reinstated him from the Voluntary Retired List, then gave him an unconditional release six days later so he could play baseball in Japan in 1974. His one-year contract with the Nankai Hawks of Osaka stipulated a reported salary of $85,000. “I feel I’m being paid for taking a vacation in a foreign country that has always fascinated me,” said Parker in a 1974 interview.34

While others may have experienced culture shock, Parker jumped into the Orient feet first and full of curiosity. “With the money, I paid off my home loan,” he recalls. “The people were wonderful. The food was terrific. The women were kind and sensitive. The people were civilized and polite. They had a lot of pitchers of Major League Baseball quality and some actually came over to play in the majors. Sadaharu Oh was a terrific hitter. What I liked most about playing in Japan was seeing the sights.” 35

Parker’s stay in the Far East lasted one season. In 128 games he hit .301 and launched 15 home runs. His defensive skills remained razor sharp: he won the Diamond Glove, Japan’s version of the Gold Glove. Despite overtures from the Hawks, Parker left his playing days behind after that one season. “[L]iving in Japan is a lonely life for an American ball player,” admitted the temporary expatriate. “He’s so far away from his home and his friends and the language barrier is always there. Don’t get me wrong, though. The people in Japan treated me just super. I couldn’t ask for any better treatment.”36

In the mid-1980s, Parker became a Dodgers instructor, passing on his knowledge about bunting, hitting, and base running. That period coincided with the end of Parker’s acting career, which began with “The Undergraduate,” a 1970 episode of The Brady Bunch. Greg Brady has difficulty in his math class because he has a teenage crush on Linda O’Hara, his math teacher, played by Gigi Perreau. Greg’s father, Mike, has a meeting with Miss O’Hara to explain the situation when he discovers that Wes Parker is her fiancé. It’s a bit of fiction because Parker is a bachelor who never married. Introducing Greg to one of his Dodger heroes has the effect his dad had hoped for—shocking him out of his crush. Parker promises two tickets to Opening Day if Greg gets an A.37

“When we shot that episode,” Parker recalls, “the production crew was running late. We were supposed to shoot at 1:00 p.m., but didn’t get the scene done till 4:30. I kept asking when we’d be finished because I had a game that night and I was worried that I wouldn’t get to Dodger Stadium in time.”

Guest roles followed in standout shows of the 1970s: McMillan & Wife, Police Story, The Six Million Dollar Man, Police Woman. In 1977, he had a starring role in the first-run syndicated program All That Glitters, a soap opera parody that lasted 65 episodes. Television producer and the show’s creator Norman Lear—who helmed megahits All in the Family, Maude, The Jeffersons, and Good Times—attempted to capitalize on his other soap opera parody, Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman. In All That Glitters, the characters lived in an alternate universe where traditional roles were reversed—women brought home the bacon and men cooked it. If a man was in the workplace, it was usually as a secretary.

“Athletes are used to taking direction and being on time, which are crucial parts of acting,” Parker said. “One hard part for me was digging down deep for emotions because athletes are used to the discipline of sports where we put emotions aside. In front of about 50 strangers in the crew, it’s difficult sometimes to find the emotion required for the scene. After my appearance on The Brady Bunch, I was successful primarily doing commercials. I did spots for Excedrin PM and Pillsbury Instant Dessert. I liked that area of entertainment. It was very businesslike, compared to film and television, which are ego driven. Broadcasting was another opportunity for me to be in front of the camera. I really enjoyed it because I had been trained to analyze the game when I played. On the Dodgers ball club, we were always talking about the finer points of baseball. There are so many details about the game, so I tried to educate the audiences about what was going on and why. I did that for about six years with the USA Network on Thursday Night Baseball. My job ended because ESPN outbid USA. ESPN had its own in-house teams.”38

Parker has two hobbies that reflect his two careers: “I collect baseball memorabilia. My collection has about 800 first editions of baseball books, a ball signed by Babe Ruth and a 1954 set of Topps baseball cards. I used to collect Topps cards as a kid. Film collection is also important to me. My fascination with films started when I was nine years old. Mae West, W.C. Fields, and cowboy movies were my favorites. Gene Autry. Roy Rogers. Hopalong Cassidy. My mom didn’t allow us to have a television set when I was younger, so I complained to my father. He bought a projector and rented out 16 millimeter films. We finally got a television set in 1953, when I was 14.

“I’m not an expert on foreign films, but I think they’re terrific. My two all-time favorite films are Casablanca, which seems to be everyone’s favorite, and Out of the Past, starring Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, Jane Greer, and Rhonda Fleming. Out of the Past is a film noir story about a double-crossing woman. Great script, spectacular lighting. I have a collection of about 500 films on DVD.”39

There are, indeed, many sides to the Dodger first baseman who fielded ground balls with the precision of a surgeon. A 1971 profile in Sports Illustrated highlighted his proficiency at golf and bridge, in addition to cultured hobbies of music appreciation and reading. A follow-up in 2002 mentioned his collection of 60 vintage movie posters and French advertising posters.40

Parker still plays bridge and golf, in addition to following all sports on television. He is a particular fan of the University of Connecticut women’s basketball team and its coach, Geno Auriemma. “They play the game properly and you can watch them for four years instead of having them turn pro after just one or two seasons. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a better-coached team or a smarter one, except maybe Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers,” says Parker.41

Baseball, while it was his job—and his passion—held an allure for Parker beyond the success he attained. “I didn’t just play to achieve stats. I played because I wanted to be a part of the game. In turn, I met some wonderful guys who became close friends and, in some cases, mentors. Ernie Banks and Bill White are the cream of the crop of human beings. I’ve met and worked with really fabulous people. It means a lot to me that I was able to share my life in baseball with them.”42

Last revised: April 19, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Tom Schott and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 Jim Murray, “Bel-Air Escapee,” Los Angeles Times, May 20, 1969.

2 Ibid., “Harvard Product,” April 7, 1965.

3 Ibid.

4 Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, January 28, 2018.

5 Charles Maher, Los Angeles Times, May 30, 1969.

6 Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, February 12, 2018; Ed Rumill, “Parker helped L.A. in two spots,” Christian Science Monitor, September 9, 1965.

7 See note 4.

8 Patrick McNulty, “What’s a Nice Kid Like You Doing in a Game Like This, Wes?,” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1971.

9 Ross Newhan, “Parker Confident He Can Keep Bat Spree Going Upon Recovery.” Los Angeles Times, July 27, 1969.

10 Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, February 12, 2018; McNulty “What’s a Nice Kid?”

11 Steve Jacobson, “Dodgers’ Prize Rookie Didn’t Coast ‘em a Dime,” Newsday, March 28, 1964; Nealon.

12 Previous paragraphs based on telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, January 28, 2018.

13 Bob Hunter, “Wes Makes ‘Em Forget Big Frank,” Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, March 18, 1964.

14 Ibid.

15 “Wes Parker In Mayo Clinic,” & Frank Finch, “Wes Parker Plans Weight Program,” Los Angeles Times, October 7, November 20, 1965.

16 Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, February 12, 2018; Frank Finch, “Wes Parker Muscle Man Now,” Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1965

17 Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, January 28, 2018..

18 William Leggett, “In Greek It’s Los Angeles,” Sports Illustrated, March 22, 1971.

19 Frank Finch, “Duke’s Job: Bring Out Beast In Wes,” Los Angeles Times, March 5, 1967.

20 Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, February 12, 2018 .

21 Ibid.; John Wiebusch, “Parker Delivers Again, Credits Dixie Walker,” Los Angeles Times, April 21, 1969.

22 Ross Newhan, “Parker Hits For Cycle As Dodgers Win In 10th,” Los Angeles Times, May 8, 1970.

23 Ross Newhan, “Wes Parker: The Complete Baseball Player,” Los Angeles Times, February 7, 1971.

24 Ibid., “High Baseball Salaries Make No Sense, Says Wes Parker,” March 24.

25Jim Murray, “Stylish Miscast,” ibid., March 31. Parker offered his opinion on baseball salaries five years before Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally exploded the free agency barrier, thanks to the arbitration decision by Peter Seitz allowing players to bargain.

26 Jim Murray, “He Came to Play,” Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1972.

27 Dwight Chapin, “Parker: Baseball Beautiful but Not Only Life,” Los Angeles Times, ibid. November 26, 1972.

28 “Dodgers’ Golden Glove, Parker, Retires at 33,” ibid., November 22.

29 Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, January 28, 2018. Wills, too, retired after the 1972 season when the Dodgers released him.

30 Dave Anderson, “The Human Values of Two Ex-Dodgers,” Los Angeles Times, November 29, 1972.

31 Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, January 28, 2018.

32 Parker concluded that three reasons led kids to experiment with drugs: “First, it’s a rebellion against what they seem to think is a ‘dreary future.’ Second there’s the pressure of being part of the in-group, and, third, there’s the adventure of doing something that’s forbidden.” Bob Hertzel, “Dodger Pair Fights Drugs,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 21, 1971.

33 AP, “Dodgers 20,000, Drugs 0,”, February 14, 1971.

34 Ibid. “Wes Parker,” Baseball Hall of Fame Biography Sheet, Cooperstown, NY; Bill Becker, “Wes Parker, the Compleat Athlete, Heads for Japan,” New York Times, January 13, 1974.

35 Becker, “Wes Parker, the Compleat Athlete.”

36 UPI, “Parker Quits Baseball Again,” February 26, 1975.

37 Bob Hunter, “Joshua, Parker, Return to ‘Active’ Status,” Dodger Blue, March 15, 1984; The Brady Bunch, “The Undergraduate.” Directed by Oscar Rudolph. Written By Sherwood Schwartz and David P. Harmon. ABC, January 23, 1970.

38Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, January 28, 2018.

39 Ibid.

40 See note 18; Hali Helfgott, “Wes Parker, First Baseman,” Sports Illustrated, April 1, 2002.

41 Email, Wes Parker to David Krell, February 14, 2018, in author’s possession.

42 Telephone interview, author with Wes Parker, January 28, 2018.

Full Name

Maurice Wesley Parker

Born

November 13, 1939 at Evanston, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.