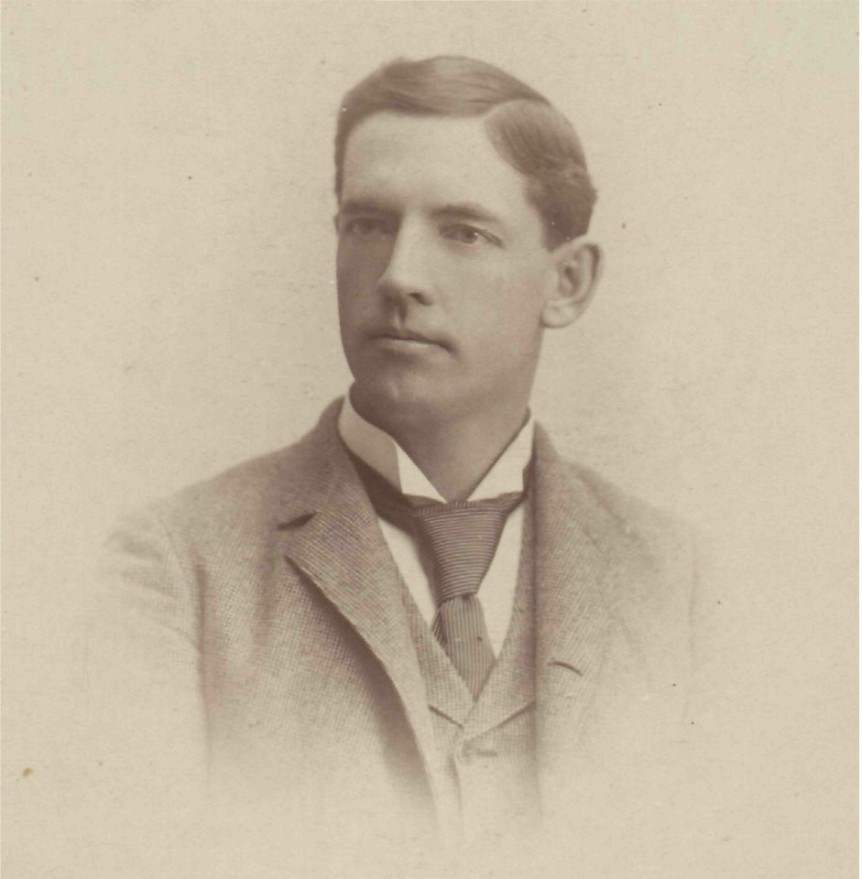

Bob Emslie

Bob Emslie, National League umpire and newlywed in 1893. (Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Robert Daniel Kean Emslie, the least-known famous umpire in baseball history, made his earthly debut on January 27, 1859, in Guelph, Ontario, the fourth son and seventh of eight children born to Alexander and Mary Graye,1 immigrants from Aberdeenshire, Scotland. (Emslie is a Scottish habitational surname meaning “woodland clearing.”) With his last breath on April 26, 1943, a lifelong love affair with baseball that began at age 6 as a batboy came to an end, and with it a career by any standard one of the most extraordinary in baseball history. He had spent 54 of his 84 years, the years 1882 through 1935, in professional baseball, six as a player and 49 as an umpire,2 46 in the major leagues, calling em for 35 seasons then serving 11 years as umpire supervisor. Solid in stature at 5-feet-11 and 180 pounds, Emslie was a gifted athlete, excelling in sports requiring very different skills: major-league baseball pitcher, international champion in trapshooting and curling, and late in life an accomplished golfer and bowler.

Bob was not to the manor born, his father a tailor, but he was raised in the hotbed of Canadian baseball, as a youth caught up in the diamond exploits of championship teams, first the Guelph Maple Leafs, then the Tecumsehs after moving to London in 1868.3 He started playing amateur ball in the outfield but, impressed by Fred Goldsmith’s “skew ball” (i.e. curveball), took to the box. In 1879 he began pitching for pay with the Harriston Brown Stockings, employed as head clerk of the leading hotel in town, and paid $1.50 to $1.75 a game.4 In 1881 he joined the St. Thomas Atlantics, and while he was barnstorming with the team through Eastern American states in 1882, his sharp breaking curveball so impressed the Camden Merritt of the Interstate Association that they tendered his first professional contract, $150 a month. When the Merritt folded in July 1883, Emslie reached the major leagues with Baltimore of the American Association. His devastating curveball portending a brilliant career, the right-hander in 1884 started and finished 50 games for the sixth-place Orioles, winning 17 of his first 21 games, and ending the season 32-17 with one tie. Posting a 2.75 ERA in 4551/3 innings, he struck out 264 while walking only 88. His major-league career ended abruptly the next year in August due to a shoulder injury, probably a SLAP tear,5 that began in 1884 and worsened while he was pitching in New Orleans during the winter of 1885. He later recalled, “I suddenly felt a stinging sensation in my shoulder. This thing went on for some time, until no matter what kind of a ball I threw, it gave me great pain, and then I knew my arm was dead.”6 Although that season’s 3-14 record and 4.71 ERA reduced his majorleague career record to a mediocre 44-44 and 3.19 ERA, 362 strikeouts against 165 walks evidenced his once-promising career.

Comeback efforts in the minors, with Toronto of the International League in 1886 and Savannah of the Southern Association in 1887, failed, but his baseball career inadvertently resumed on June 30, 1887, when he was summoned from the stands to call a game in Toronto after the scheduled umpire fell ill. Admitting “it was purely a matter of accident how I came to follow umpiring as a means of livelihood,”7 he umpired with the International League for the rest of that season and the next two, advancing in 1890 to the majors with the American Association. He began the 1891 season in the Western Association, then returned to the majors in August with the National League, where he remained for 45 years. By then a proven career umpire, in 1893 he married Helena Ward, with whom he had two children, Helen Elizabeth (“Kitty”) in 1895 and Robert John (“Jack”) in 1900.

Toiling during the three most contentious and difficult decades umpires ever faced, from the violent, umpiring-baiting 1890s through the Deadball Era, Emslie survived injury from thrown and batted balls, physical and verbal assaults from players and fans, and criticism in the press to become the respected, even revered, titular “dean of umpires.” He was the acknowledged master of the rule book, fellow arbiter Cy Rigler declaring that Emslie “knows more about the baseball rules than all the other National League umpires together.”8

Bob performed the common aspects of umpiring in an uncommon way, being respected by players and managers alike for his temperament, style in handling disputes, and ability to “run” the games in an efficient and orderly manner. Of his work in the turbulent 1890s, Jacob Morse of the Boston Herald asserted: “Undoubtedly he has got to be the best umpire who ever handled a game. Umpires there have been who have been as good in the mere minutiae of the game, but none to equal him when it comes to discipline, tact, personal habits, temperance, reliability and ability.”9 Christy Mathewson agreed, regarding Emslie as “one of the finest umpires that ever broke into the League,” “the sort of umpire who rules by the bond of good fellowship rather than by the voice of authority.”10 Reflecting upon his career, Emslie said: “I always got along very well with the players and I don’t think I ever had an enemy in the game.”11

Emslie understood that kicking was part of the game: “Of course it is inevitable that players will protest when a decision is given that seems to them erroneous. Umpires make mistakes the same as other people and it is only natural that there should be a protest if the player gets the small end of a decision, but I will put him out of the game just as soon as I feel that he is talking back too much or uses language which he should not use.”12 His first ejection came on July 21, 1892, the Browns’ Jack Crooks; his second came two years later when he tossed the New York Giants’ Jack Doyle and fined him $5 for “a series of foul names unfit for publication.”13 On May 19 at the Polo Grounds, he had the distinction of giving viciously vituperative John McGraw his first ejection as Giants manager for “raucously expressing his disagreement.”14 Being a former player, Emslie understood the competitive spirit, so typically each season he recorded the fewest fines and ejections on the staff. While the number of his ejections increased from 1901 to 1910, during his career Emslie tossed players far less frequently (once every 26 games) than did his National League contemporaries.15

Players so respected Emslie for his ability and integrity that they would come to his aid in time of need. In an 1899 game, when irate Brooklyn fans jumped onto the field and mobbed him after he had called Tom Daly out at home plate in a 2-1 loss to Boston, Daly and Bill Dahlen shielded him from the crowd with their bats.16 And in 1907, when fans at the Polo Grounds poured onto the field bent on assault, Giants pitcher Joe McGinnity ran from the dugout, and threw an arm around Bob, “occasionally warding off a stray wallop that some angry fan aimed at the umpires head” until police arrived to restore order.17

Team owners also appreciated his long and distinguished service. In recognition of his 25 years of service, the league in August 1916 honored him with “Emslie Day” in Brooklyn, the ceremonies replete with tributes and gifts, including from league President John Tener 25 double-eagle gold coins worth $20 each, and a diamond stickpin from his fellow umpires.18

He called his last game on September 28, 1924, leaving the field with numerous major-league umpiring records. At 65 years and 8 months the oldest ever to umpire a game, he had worked the most seasons, 35, and the most games, 4,231, and achieved numerous “firsts”: the first umpire to work four decades, to call 2,000, 3,000, and 4,000 games, to be given a celebratory “day,” and to be appointed staff supervisor. In 1935 he retired with three service milestones: 45 consecutive years with one league, 46 years in the majors, and 54 in professional baseball – all longer than anyone else in history. With Bill Klem, he still holds the record for the fastest game in baseball history, 51 minutes on September 28, 1919, and until 1969 he had worked the most no-hitters, eight, in the National League.

He had also achieved two personal distinctions: the first Canadian full-time major-league umpire, and the first and only major leaguer to wear a toupee during his career. It has been said that Emslie’s hair loss was due to the stress of umpiring during the tumultuous 1890s, but it actually began in 1885 in Baltimore, and was caused by genetics. Vanity was not the only reason for donning a toupee. It was commonplace for men in the late nineteenth century to regard hair loss as a sign of decreased manliness, and with masculinity accentuated among athletes, it was understandable for an authority figure like an umpire to cover baldness. Although never, as has often been claimed, being nicknamed Wig, he was extremely sensitive about baldness, brooking no references to his hairpiece. He took “a good deal” from Jack Doyle until Doyle suggested Emslie get “a hair restorer,” a comment that resulted in Doyle’s being escorted from the grounds by a policeman.19 And when John McGraw shouted in a voice loud enough to be heard by spectators that Emslie should get a box of hairpins to fasten his toupee, the umpire, embarrassed by and irate at “one of the most tragic, brutal cases of ‘show up’ he had ever experienced,” ejected the Giants manager for five days and hit him with a sizable fine.20

Unfortunately, Bob Emslie is most famously (or infamously) remembered for his role (or nonrole) in the game between the New York Giants and Chicago Cubs at the Polo Grounds on September 23, 1908, the so-called “Merkle Boner” game, unfairly criticized for failing to notice that the Giants’ Fred Merkle failed to reach second base after the apparent game-winning hit. Emslie, who said he “had to fall to the ground to keep [the batted] ball from hitting me,” had properly been looking to see if the batter-runner reached first base, as that concluded the play. Watching to see if Merkle touched second was the home-plate umpires duty, so Hank O’Day properly made the call that resulted in a tie game, replayed at the end of the season for the first time in major-league history.21

Because of the Merkle incident, John McGraw dubbed Emslie “Blind Bob.” Emslie, an accomplished trapshooter, took offense. Several stories circulated as to how he demonstrated his visual acuity to the Giants manager. One version is that he showed up one afternoon during a Giants practice with a rifle – not to shoot the Giants manager, but to demonstrate his eyesight. After placing a dime on the pitcher’s rubber, he retreated behind home plate, took aim, and sent the coin “spinning into the outfield.” Another version says he put the dime on a matchbox on second base. On another occasion, he reportedly challenged McGraw to a contest – shooting at apples set on second base. McGraw declined, sarcastically quipping “Maybe you can see apples, but you can’t see baseballs.”22

Statistically, Emslie is firmly entrenched in the major-league record book with career totals that will likely never be surpassed. He is tied for fourth in number of seasons, 35, with five who umpired on four-man crews,23 and 16th with Al Barlick in games umpired with 4,231, the most by an umpire working only on two-man crews, and the most by a former major-league player. He also ranks fourth in home-plate games worked, 2,356,24 remarkable inasmuch as he spent 15 years umpiring only the bases.

More indicative than statistics of Emslie’s prominence as an umpire are the views of contemporaries who had first-hand knowledge of his umpiring. Honus Wagner ranked Emslie and Bill Klem “the ideal umpires” during his 20-year Hall of Fame career, 1897-1917, regarding Emslie “the greatest of all the umpires on base decisions.”25 Hall of Fame umpire Bill McGowan agreed, calling Emslie “the greatest base umpire of all time,” and thought Bill Klem and Emslie “the best umpiring team the game ever knew – Klem at the plate, Emslie on the bases.”26 Hall of Fame umpire Billy Evans considered Emslie “one of the greatest umpires the game ever produced.”27 Sportswriters, too, thought him “one of the greatest umpires of all time.”28 The first edition of Who’s Who in Major League Baseball said of Emslie: “Whenever old-time fans get together and start chattering about diamond immortals you’ll hear them paying tribute to Bob Emslie, who was one of the greatest of them all in the days of Hurst, O’Loughlin, Sheridan, O’Day and Tommy Connolly.”29

Famous in his day, Bob Emslie faded into historical obscurity owing to the lone omission in his long and distinguished career: He never umpired a World Series. He had umpired three Temple Cup series, baseball’s postseason showcase games in the 1890s, but beginning in 1905, the onset of hyperopia (farsightedness) led to increasing criticism of his calling pitches, and from 1910 to the end of his career he essentially umpired only the bases.30 Glasses would have corrected the problem, but it then was an unspoken rule that umpires not don spectacles, as it would be taken as an indication of deficient eyesight; the eyeglass-ceiling for umpires was not broken until 1956.

Immediately upon Emslie’s death, sportswriters and ex-National League President John Heydler called for his enshrinement in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Only players were then deemed eligible for election, but in 1946 the Hall announced its Honor Rolls of Baseball, recognizing the significant contributions to the game of those precluded from official induction. Bob Emslie was one of 11 umpires selected.31 Beginning with Bill Klem and Tommy Connolly in 1953, 10 umpires have been inducted into the Hall, Emslie’s career statistics equal to or greater than most.32

Interred next to his wife in Section 92 of the mausoleum in St. Thomas West Cemetery, Bob Emslie eventually, if posthumously, achieved baseball immortality, when he was elected in 1986 to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame, and in 2004 to the Guelph Sports Hall of Fame as a player and umpire. And he is one of only three umpires for whom a baseball facility has been named.33 The lone survivor, Emslie Field in St. Thomas’s Pinafore Park, is a fitting living memorial to the achievements and contributions to baseball of Robert D. Emslie.

Notes

1 Graye, the traditional Scottish spelling, was subsequently rendered Gray.

2 In 1887 he both played his last game and umpired his first game.

3 David L. Bernard, “The Guelph Maple Leafs: A Cultural Indicator of Southern Ontario,” Ontario History, vol. 84, no. 3 (September 1992), 1-23; Brian Martin, The Tecumsehs of the International Association: Canada’s First Major League Baseball Champions (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2015).

4 New York Sun, July 28, 1918; New York Times, April 29, 1943.

5 SLAP (Superior Labrum Anterior and Posterior) tears, labral tears of the cartilage where the humerus bone joins the scapula shoulder blade to stabilize the shoulder joint, are common in forceful movements of the arm above shoulder level, such as overhand pitching.

6 The Sporting News, February 1, 1896.

7 Robert D. Emslie, “Ramblings of an Umpire,” Baseball Magazine (November, 1908): 18.

8 Boston Globe, August 17, 1920. See also the Wilmington Evening Journal, August 2, 1920, and Vancouver Sun, August 22, 1920.

9 Undated 1897 Boston Herald article, Robert Emslie Collection, Elgin County Museum, St. Thomas, Ontario; Baltimore Sun, October 2, 1897.

10 Christy Mathewson, Pitching in a Pinch (New York: Putnam’s, 1912), 175.

11 Unidentified newspaper article, Emslie Collection.

12 Emslie, “Ramblings,” 18.

13 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 22, 1892; Sporting Life, June 23, 1894.

14 New York Sun, May 20, 1903; Lou Hernández, Manager of Giants: The Tactics, Temper and True Record of John McGraw (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2018), 33.

15 Bill Klem 346, Cy Rigler 272, Jack Sheridan 264, Tommy Connolly 261, Hank O’Day 238, and Jim Johnstone 208. Indeed, Deadball Era umpires, including Emslie, constituted 10 of the 12 with the most ejections. David W. Smith, Table 5, https://www.retrosheet.org/Research/SmithD/EjectionsThroughTheYears.pdf.

16 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn Citizen, Brooklyn Daily Times, and Brooklyn Times Union; New York Times, New York Tribune, New York Sun, New York World; Boston Globe; September 8 and 9; The Sporting News, September 9; Sporting Life, September 16, 1899.

17 New York World, May 21-22; New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Boston Globe, and Washington Post, May 22, 1907.

18 New York Times and New York Tribune, August 10 and 13, 1916; Brooklyn Daily Eagle and Boston Globe, August 13, 1916.

19 Baltimore Sun, and Washington Evening Star, July 30, 1897.

20 New York Tribune, May 26; Syracuse Post-Standard, May 27, 1908; Allen Sangree, “As the Umpire Sees Them,” Collier’s, Volume 41 (September 19, 1908): 23; William Patten, and Joseph Walker McSpadden, eds., The Book of Baseball: The National Game from the Earliest Days (New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1911), 110.

21 David W. Anderson, More Than Merkle: A History of the Best and Most Exciting Baseball Season in Human History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), New York Times, September 24-25; New York Tribune, Chicago Tribune, September 24 and 27; New York Tribune, October 3; New York Evening World, October 5; and Sporting Life, October 17, 1908. For various historians’ views on the game, see the special Merkle edition of the SABR Deadball Era Committee newsletter, “The Inside Game,” vol. 8, no. 4 (September 23, 2008), at https://sabr.org/research/deadball-era-research-committee-newsletters/.

22 Raymond Schuessler, “You Can’t Kill the Umpire,” The American Legion Magazine (April 1976): 26; James M. Kahn, The Umpire Story (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1953), 39.

23 He trails Joe West, 44 seasons (through 2021), and Bill Klem and Bruce Froemming, 37 seasons.

24 Retrosheet’s 2,357 includes him at the plate on April 17, 1917, but the Cincinnati Enquirer on April 18 specifically reports him calling plays at first base.

25 Washington Evening Star, December 24, 1923; John B. Kennedy, “The Flying Dutchman,” Collier’s, vol. 85, no. 15 (April 12, 1930): 81.

26 The Sporting News and the Wilmington News Journal, March 17; Wilmington Morning News, April 13, 1954.

27 Boston Globe, March 6, 1915.

28 Buffalo Morning Express, January 11, 1914; Pittsburgh Gazette, January 28, 1924.

29 Harold “Speed” Johnson, comp., Who’s Who in Major League Baseball (Chicago: Buxton Publishing, 1933), 448-449.

30 From 1910 to 1924, he worked the plate only 11 times, thrice in 1913 and 1918, and none in eight of those seasons.

31 Five managers, 11 executives, 12 sportswriters, and 11 umpires were chosen. The other umpires selected were Bill Klem, Tommy Connolly, Bill Dinneen, Billy Evans, John Gaffney, Tim Hurst, “Honest John” Kelly, Francis “Silk” O’Loughlin, Tom Lynch, and Jack Sheridan.

32 His 35 seasons as a regular member of the staff is second only to Klem’s 37, and at least a decade longer than four other enshrinees. That he umpired more games than five members of the Hall is the more noteworthy as he worked fully half of his seasons, 1890-1908, as a single umpire, the others on two-man crews.

33 The baseball field at the University of Kansas was named after Ernie Quigley, National League umpire from 1913 through 1938, who also briefly served (1944-1950) as the school’s athletics director. John Ducey Park in Edmonton, Alberta, honors an Edmonton baseball executive who had previously umpired amateur and minor league ball between 1931 and 1945. Money has since trumped tradition, both facilities having been renamed in honor of financial donors.

Full Name

Robert Daniel Emslie

Born

January 27, 1859 at Guelph, ON (CAN)

Died

April 26, 1943 at St. Thomas, ON (CAN)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.