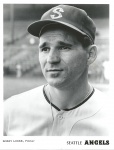

Bobby Locke

The well-traveled right-handed pitcher Bobby Locke spent the month of September 1964 on the Phillies roster after a call-up from Little Rock. He pitched in eight games, three of them during the team’s fatal ten-game losing streak, including the one in which Chico Ruiz’s steal of home launched the losing streak. (Art Mahaffey was on the mound when Ruiz committed his brazen act.) Locke worked 19 1/3 innings, with no decisions and a 2.79 earned-run average.

The well-traveled right-handed pitcher Bobby Locke spent the month of September 1964 on the Phillies roster after a call-up from Little Rock. He pitched in eight games, three of them during the team’s fatal ten-game losing streak, including the one in which Chico Ruiz’s steal of home launched the losing streak. (Art Mahaffey was on the mound when Ruiz committed his brazen act.) Locke worked 19 1/3 innings, with no decisions and a 2.79 earned-run average.

In an interview with the author, Locke accepted some responsibility for the fifth loss of the losing streak. On September 25 he faced Joe Torre of the Milwaukee Braves in the top of the tenth inning. With the score tied 3-3, a runner on second, and one out, Phillies catcher Clay Dalrymple signaled for a fastball, but Locke shook off the call and threw a curveball, which he described as “the worst pitch of my career.” Torre turned on the pitch for a two-run homer. “I don’t know why I wanted to throw him a curve. My curve was my worst pitch. I probably should have thrown a slider,” Locke said.1 The Phillies tied the game in the bottom of the tenth, but lost 7-5 in 12 innings.

Lawrence Donald Locke was born on March 3, 1934, in the little town of Rowes Run in the rough mining country of Southwestern Pennsylvania about 40 miles southwest of Pittsburgh. He was the eighth child of coal miner John Locke and his wife, Anne The family eventually grew to total six sons and four daughters.

Sometimes going by Larry but usually known as Bobby as early as he can remember, the 5-foot-11, 185-pound right-handed pitcher played parts of nine seasons from 1959 to 1969 for five major-league clubs: the Cleveland Indians, the St. Louis Cardinals, the Phillies, the Cincinnati Reds, and the California Angels. Locke was also on the Chicago Cubs’ roster for spring training in 1962.

Bobby saw early success as a pitcher in PONY league baseball, and remembered once striking out everyone on the other side.2 A multiple-sport star at Redstone High School in Republic, Pennsylvania, he played fullback and defensive back in football and made several all-star teams. He excelled in baseball as a pitcher, throwing two no-hitters and averaging 13 strikeouts a game. His 1952 team went undefeated, and he pitched a one-hitter with 13 strikeouts to win the state championship. Locke played in the Sandlot Classic at the Polo Grounds in New York City as a member of the 1952 USA Baseball All-Star team.

Locke accepted a football scholarship to Arizona State University but returned home to focus on baseball early in his first gridiron season. “I punted in the first game, and decided I wasn’t going to play any more football. When I realized that, I hitchhiked back home.”3

Cleveland Indians scout Laddie Placek signed Locke in 1953 as an outfielder and pitcher, offering him a $6,000 bonus. The 19-year-old began his professional career in Class D with Daytona Beach and led the Florida State League with 247 strikeouts his first season. He had a true breakout season in 1956 at Reading of the Class A Eastern League with an 18-9 record and a 2.43 ERA in 28 starts. Then he spent the next two years, 1957-1958, in military service.

Back in professional baseball in 1959, Locke opened the season with the Indians’ Triple-A San Diego team. He had four shutouts and a 1.63 ERA by mid-June, when he got the call from the Indians. He debuted in the big leagues with a starting assignment against the Boston Red Sox on June 18, and in his second at-bat he hit his only major-league home run, a three-run shot off Frank Sullivan over Fenway Park’s Green Monster wall in left field. The Indians moved Locke to the bullpen in early August for the remainder of the season, where he posted a 1.03 ERA in 13 appearances.

Locke started the 1960 season in the minors, but was called back to the Indians in early June to complete his best year in the big leagues. With a 3.37 ERA, he reached his career high of 11 starts and 123 innings pitched, and threw his only two big-league shutouts.

Over the next winter, Bobby sold tickets for the coming season, meeting the public and making speeches. He began to realize he had never developed the confidence he needed as a big-league pitcher and found a good resource in Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking. “In reading the book, I realize now I was taking the negative approach,” Locke reflected. “It’s easy to see a fellow can’t get anywhere in life unless he has confidence in himself, and in baseball, confidence is probably the most important thing.”4

Locke stayed with Cleveland the entire 1961 season, his only full season in the majors. After the season the Indians traded him to the Chicago Cubs for second baseman Jerry Kindall.

The Indians clearly got the better side of the trade. Kindall played in 154 games in 1962, hit 13 home runs, and batted .232, while Locke struggled just to finish spring training with the Cubs’ “College of Coaches” employed by team owner Phillip K. Wrigley. At one spring game, with a stiff arm on the mound, Locke simply walked off the field without talking to anyone. “With this all-coach system, I just didn’t know who to talk to,” he said later.5

Locke then found himself on three other clubs in the next three months. The Cubs sent him to the St. Louis Cardinals three days before the season started, for outfielder Al Herring and cash. After one two-inning appearance, the Cardinals traded him to the Phillies for pitcher Don Ferrarese. By early June the Phillies had demoted Locke to Triple A Buffalo. In July, he went on the disabled list with a leg injury.

Locke continued his journeys back and forth. In 1963 he was up with the Phillies from early August until the end of the season. In 1964 he was called up in September after winning 11 games as a starter and reliever for the Phillies’ Triple-A team in Little Rock.

Shortly after the 1964 season the Phillies sold Locke’s contract to the California Angels. In 1965 he was 12-5 with the Angels’ Seattle team in the Pacific Coast League, before being traded in late July to the Cincinnati Reds for pitcher Jim Coates and a player to be named later. He spent the full 1966 season in the minors, and the Angels purchased his contract back from the Reds in early June. He spent most of the 1967 season with Seattle again before he received a call-up for the last month of the season. He was 3-0 in nine September appearances, all but one game in relief, with a 2.31 ERA.

A starter throughout his early career, Locke found himself in the bullpen for most of his major-league career. He became frustrated pitching in relief when he was mainly a starter in the minor leagues. After early June 1961, he made just one start (in 1967) in 101 appearances through 1968. “I was really a starter,” Locke said. “That’s all I ever did, and that moving back and forth to the bullpen really took a toll on my arm.” (During 14 minor-league seasons Locke started 236 games.)6

Various injuries resulted in a drop in the speed of Locke’s fastball and blocked his success. He remembered one particular relief appearance early in his career. He struck out Julio Becquer, first baseman of the Washington Senators, on a curveball in the dirt. With that pitch Locke felt a small pop in his throwing elbow but thought little of it until he sat in his hotel room later that ednight. Then he felt a burning “like a match,” he recalls, and he never could throw as fast again.7

Later in his career, Locke uncovered a hidden wrist injury dating back to high-school football. He underwent x-rays after being hit by a pitch on his wrist. Dr. William “Bill” Hutchinson, brother of big-league manager Fred Hutchinson, discovered a small bone in the wrist that had not healed properly after an earlier break. Locke never knew he had a broken bone, though his wrist often swelled during his career. Dr. Hutchinson told him he had a “one in a million” chance to pitch in the major leagues with such an injury.8

Locke pitched for the last time in the big leagues on September 29, 1968, for the Angels. In 1969 he appeared in 44 minor-league games for two Triple A teams, the PCL Hawaii Islanders and the Syracuse Chiefs, who were then an International League affiliate of the New York Yankees.

Locke held a very unusual offseason job. In late 1964 he obtained a Pennsylvania beauty operator’s license. “It’s a lot different than baseball,” he said. With the creativity involved in hairdressing, “you can cover up your mistakes. You can make up things as you go along.” He imagined opening a “beauty saloon” that would offer customers both hair styles and liquid refreshments.9 In reality Locke did very little actual hair styling. He worked as a salesman for a hair products company that required the license.10

After his baseball days, Locke returned to his home territory and worked in Western Pennsylvania for the U.S. Postal Service, then spent 26 years in sales for Frito-Lay. He and his wife, Carma, had three children: Kenneth, a nuclear engineer; Robert, employed by Comcast; and Lauren, married to a chiropractor.

The best memory of Locke’s career came from his first big-league appearance, when he faced the Red Sox and their superstar slugger Ted Williams. He hit Williams with a pitch in the fourth inning and remembered reading Williams’s comments in the papers the next day: “Wow, that kid really throws hard!” Bobby proudly reflected, “That meant a lot, coming from a guy like that, one of the best ever.”11 He faced the Splendid Splinter eight other times and gave up only one hit, a single, walked him once, and struck him out four times.

As of early 2013, Locke still lived in his home area of Southwestern Pennsylvania. He was inducted into the Mid Mon (Monongahela) Valley All Sports Hall of Fame and the Fayette County Sports Hall of Fame.

Last revised: August 27, 2014

This biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Notes

1 Paul Geisler telephone interview with Bobby Locke, April 1, 2011.

2 Geisler interview.

3 Fayette County Hall of Fame. http://fayettecountysportshalloffame.com/locke.html.

4,Hal Lebovitz, “Twirler Locke Chucks Doubts – Kid Sure He Can Notch 15 Wins,” The Sporting News. January 25, 1961.

5 “Bruins Unlock Doghouse, Swap Locke to Cardinals,” The Sporting News. April 18, 1962.

6 Geisler interview.

7 Geisler interview.

8 Fayette County Hall of Fame website..

9 Larry Merchant, “He Makes Gal’s Hair Curl!” Baseball Digest, December-January, 1964.

10 Geisler interview.

11 Geisler interview.

Full Name

Lawrence Donald Locke

Born

March 3, 1934 at Rowes Run, PA (USA)

Died

June 4, 2020 at Dunbar, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.