Butch Schmidt

On March 1, 2012, a businessman named Andrew W. Schmidt III died in Baltimore, Maryland, the city of his birth. He was 80 years old. For 38 years, until the company closed in 1991, Schmidt had operated A.W. Schmidt and Son, a wholesale meatpacking house on Harford Road in Baltimore. The company had been in that general location, and in the Schmidt family, since it was founded in 1880 by Schmidt’s grandfather, Andrew W. Schmidt, Sr.

On March 1, 2012, a businessman named Andrew W. Schmidt III died in Baltimore, Maryland, the city of his birth. He was 80 years old. For 38 years, until the company closed in 1991, Schmidt had operated A.W. Schmidt and Son, a wholesale meatpacking house on Harford Road in Baltimore. The company had been in that general location, and in the Schmidt family, since it was founded in 1880 by Schmidt’s grandfather, Andrew W. Schmidt, Sr.

At first glance there would seem to be little connection between the owner of a Baltimore meatpacking plant and one of the most surprising World Series triumphs in history. There was no mention of such a link in Andrew Schmidt’s obituary. Yet, almost 60 years before Andrew died in Baltimore, his uncle, Charles John Schmidt, also died in the city. In addition to operating the same family business, Charles had once played first base for the World Series champion Boston Braves. Throughout his life, everyone knew that Schmidt as Butch.

Butch’s father, Andrew Sr., arrived in the United States from his native Germany in 1870, when he was 18 years old. Ten years later he opened his butcher business on Harford Road, and the following year he married Baltimore resident Margaret Demling. They had five children. Butch, born on July 19, 1886, was the third, and the first of two sons. (Andrew Jr., Andrew III’s father, was born in 1899.)

Little is known about Charles Schmidt’s formative years. From an early age, however, he learned the ropes in the business that eventually provided his livelihood. In 1916 he told Baseball Magazine: “I have worked in a market ever since I was thirteen years old,” laboring side-by-side with his father at the family meat market.1 During those years he also developed skills on the baseball diamond. Playing on semipro teams around Baltimore, in a circuit known as the B&O Railway League (the February 5, 1916, edition of Sporting Life said that Schmidt got his start with the Evergreen Lawn club), the young man won “some local reputation,” although he “never took the game seriously at that time” as he was “busy learning the ins and outs of selling beef and mutton.” (Schmidt also tried another sport during those years, if only briefly. “I played one game [of football] when I was sixteen,” he later related. “Our club was made up of boys from the market and we played a crowd of clerks from uptown. Neither side knew much about football, but what we lacked in science we made up in strength.” As it happened, Schmidt’s team “grew kind of concerned lest some of those clerks should get hurt, and, well, I never played football after that.”)

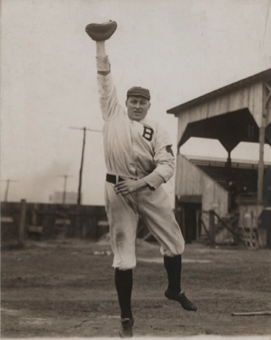

It’s likely that by 16 Schmidt was already a physically imposing young man. (By that time, too, he also may have gained the nickname Butcher Boy by which he came to be known as a major leaguer.) Years later, in his prime, it was written of the Braves’ first baseman that he was “quite a giant of a man.” At 6-feet-2 and 215 pounds, he was “a man of huge strength who is popularly supposed to be the most powerful player physically on the diamond.” He possessed a “Cy Young build” and “great strength,” and, it was predicted, “should emulate Eddie Plank as an indestructible athlete.”2 No doubt years of lugging sides of beef had helped hone Schmidt’s solid physique.

Like much of the baseball talent spawned in Baltimore in those days, Schmidt was discovered by Baltimore Orioles owner Jack Dunn, who signed the 21-year-old after watching him play on the sandlots. Whether Schmidt’s signing took place in 1907 or ’08 is unclear, but he first took the field for the Eastern League’s Orioles in 1908. Initially, Schmidt was a pitcher, a left-hander. He spent the first ten days of the 1908 season on the bench; at that point Dunn determined that the raw rookie needed seasoning, so he sent Schmidt to the Holyoke (Massachusetts) Papermakers in the Class B Connecticut State League. There, Schmidt won 10 games before Dunn recalled him in August to help with the Orioles’ drive toward the pennant. Schmidt did just that. In 11 appearances, seven as a starter, he won five games as Baltimore took the flag.

Schmidt’s work for the Orioles in 1908 gained him notice from other organizations. The man who became his greatest baseball benefactor, George Stallings, managed Newark, a Baltimore rival in the Eastern League, and was impressed with the left-hander’s performance against his club. That fall Stallings became the manager of the American League’s New York Highlanders, and he drafted Schmidt.

When Schmidt arrived at spring training in 1909, he was a newlywed. During the fall, he had wed Amelia Shuppner at her Baltimore home at 48 Harford Road. Presumably the two had been childhood friends, as the 1900 census listed the Schmidt family’s address as 78 Harford Road. Throughout their marriage of almost 44 years (they had two children, Helen and Charles John), Butch and Amelia lived on Harford Road. On his World War II draft registration Schmidt listed his address as 3014 Harford Road, the same as his business. Except for his baseball career, he was a butcher the whole time.

Schmidt appeared in only one game for the Highlanders, pitching in relief against the Tigers on May 11 and giving up eight runs. Sometime after July 4 Stallings returned the 23-year-old to Baltimore. This time things were different. In addition to his pitching prowess, Schmidt had also proved a good hitter. One day, Dunn started Schmidt at first base and the left-hander produced a 4-for-4 afternoon. That marked the end of his pitching career. Rather than keep him on the bench between starts, Dunn, as he would do several years later with another left-handed pitcher, George Herman Ruth, moved Schmidt into the lineup full time. From then on, he was a first baseman. That relief appearance against the Tigers was his only one as a pitcher in the major leagues.

Schmidt spent the next three seasons with his hometown team. As the Orioles moved from Class A to Double-A in the International League, he posted solid offensive numbers, twice topping.290. However, he seems never to have won over the hometown fans. Sporting Life later wrote that “Schmidt’s career in Baltimore was not a bed of roses, and he decided a change would prove beneficial.”3 Thus, after the 1912 season he was traded to league rival Rochester. That move eventually returned him to the major leagues.

Despite the Miracle Braves achievements, Schmidt considered 1913 at Rochester his finest season. Three years later, when he had retired from the game, he told Baseball Magazine, “Of course there is much more honor in playing on a major league team, particularly on a world’s championship team. But … I believe the season of 1913 was my best. I hit well all through the year, while in 1914, though I finished strong, I was not a consistent player.”4 Indeed, in 123 games with Rochester Schmidt batted .321, slugged .410, and “developed into a more consistent fielder than he had ever seemed before.”5 George Stallings, then managing the Braves, who “had never lost faith in the bulky first baseman”6 purchased Schmidt’s contract from Rochester in August 1913. The big first baseman played in 22 games for Boston at the end of the season and repaid Stallings’ trust, finishing with averages of .308 batting, .423 slugging, and .983 fielding. With just 23 major-league games under his belt, the 27-year-old was just a year away from achieving the pinnacle of his sport. (The transaction that brought Schmidt to Boston is unclear. While several websites indicate that the Braves purchased his contract outright, an article in the April 3, 1915, issue of Sporting Life indicated that the Braves had sent third baseman Joe Schultz to Rochester in the deal.)

The offseasons for Schmidt were never a time of rest. Each year he returned to Baltimore to work at the family business, and the fall of 1913 was no exception. Working 16-hour days at the meat market added bulk to his frame, so when 1914 spring training arrived, his challenge was to shed some weight, reduce the flab that had gathered over the winter, and get lighter on his feet. It was never an easy chore. (In February 1915, Baseball Magazine wrote that “Schmidt had an awful time getting down to weight this season.”7) In the Braves’ “miracle” year of 1914 Schmidt’s development mirrored the team’s. “During April and May,” Baseball Magazine wrote, while Boston played ineptly and floundered in last place, Schmidt “seemed clumsy, heavy-gaited, and his thickness of body made him seem thick-headed, too.” To make way for Schmidt at first base, the Braves had sold Hap Myers, 1913’s regular at that position, to Rochester, and Schmidt’s slow start caused some to question why “Stallings had displaced lean, agile, fast-stealing Myers with Schmidt.”8 As the season progressed, Schmidt began losing weight in the summer heat and his play came around. So “by the time the club was well advanced in its upward rush,” forging from last place on July 1 to win the American League pennant, “Schmidt had become a crackerjack.” Over the closing weeks, as the Braves raced for the flag, “he batted .350 and fielded like a wizard,” becoming in the process one of the league’s best first basemen.

Perhaps most impressive was Schmidt’s defense. While his batting surge at season’s end lifted Schmidt’s final batting mark to .285 (he finished second in the league in singles and third in hit by pitches), it was his glove that arguably proved most invaluable to the club. With a .990 fielding average, fourth best in the league, Schmidt finished second in assists and third in putouts, and led the league’s first basemen in double plays, teaming with future Hall of Famers Rabbit Maranville and Johnny Evers. So good had he become defensively that Schmidt drew comparisons with the man recognized at the time as the best in the business, the Philadelphia Athletics’ Stuffy McInnis.

“ ‘Butch’ Schmidt of the Braves,” wrote the Boston Daily Globe, “is the best first baseman in the game until you see ‘Stuffy’ McInnis, and ‘Stuffy’s’ the best till you see ‘Butch.’ Both are good enough to get by.”9

Never was that comparison more apparent than during the 1914 World Series. With one play, Schmidt opened many eyes and made his reputation. One scribe wrote that during practice before Game One “McInnis … made his bulky rival look foolish by his greater agility and accuracy.”10 Moreover, they also disparaged him as “a clumsy old cow,” and with the lumbering Schmidt on first base, there was little doubt that the A’s would have “unlimited fun running the bases.” But as it turned out, those notions were dispelled by the “first thrilling play of the first inning of the first game.”11

Baseball Magazine called it the play that “stunned [the A’s], gave them a wallop on the jaw, and benumbed their faculties.”12 In the bottom of the first inning, with runners on first and second and one out, cleanup hitter Frank “Home Run” Baker lifted a foul popup to the edge of the bleachers in short right field. At full speed Schmidt ran to the stands, reached in and caught the ball, then wheeled and fired across the diamond to put out the A’s leadoff man, Eddie Murphy, who was trying to advance to third base. That double play ended the threat and “then and there, something snapped in the heartstrings of Mack’s men. They never recovered.”13 Many years later, Schmidt’s obituary in the Baltimore Sun said that “Connie Mack often credited Schmidt with the play that sparked the Braves to a four straight upset.”14 In any event, it was the highlight of Schmidt’s career. He hit .294 in the World Series, batting behind cleanup hitter Possum Whitted.

That career lasted just one more year, however. In 1915, as the Braves failed to repeat their magical season, Schmidt, who was laid up for several weeks after being spiked, played in 127 games and batted hit .251. In January 1916 he wrote to Braves owner Jim Gaffney and manager Stallings advising them that he was retiring from baseball to devote his time to his family’s business. He was 29 years old.

With two years remaining on his contract, Schmidt denied that his decision had anything to do with money. Sporting Life printed a statement from him that said:

“It is with great reluctance that I am retiring from base ball, but I must take care of my business and look out for the future. There are no personal differences between the Boston club and myself, and probably the most pleasant days of my career on the diamond have been spent under George Stallings. I consider that I have several more years of major league ball before me, and at the expiration of my contract, I probably would have to stand a reduction in salary, which I would not accept. So, in order to guard against the future I think the time is ripe now for me to give up the sport. I am perfectly satisfied with my contract with Boston, but I consider at the end of possibly five years I will make just as much money out of my business as I would get by playing ball for two or three more years. If I play ball, my business is bound to suffer, and I don’t want that to happen. So, looking the situation straight in the face, I think I am taking a step in the right direction.”15

There appeared to be little reason to doubt his sincerity. Andrew Sr., his father, died in 1917, so it’s likely that if he was too ill in 1916 to continue in the business, Butch may have felt obligated to assume the responsibility of carrying on. He told Sporting Life, “So pressing is my business, I will be unable to play even Saturday ball with any team in Baltimore. I won’t play on Sunday. Perhaps I may be able to slip away once in a while to play a game during the week.”16 But there is no record that he ever did.

For a brief time there were hints that Schmidt might come back. In January 1917 Sporting Life wrote, “It is reported that first baseman ‘Butch’ Schmidt is to return to the Braves and that Ed Konetchy is to be shifted to the outfield”;17 and the next month the paper said that “ ‘Butch’ Schmidt … is becoming restless. He wants to return to his old berth and threatens to join the Braves at their training camp in March.”18 But he never did.

Schmidt ran the family business for the rest of his life. Just after retiring, he was interviewed by Baseball Magazine in his merchant’s stall at Baltimore’s Richmond Public Marketplace, where, it was reported, “a continual line of customers … stepped briskly … to drop a word with the tall butcher-ball player.”19

“I have a good trade here,” Schmidt said. “People know they can rely on my judgment of meat and upon my word and they trust me to see that they are satisfied. … Occasionally a woman will stop and inquire about how we kill the animals which furnish us with meat. … (M)ention of killing … make[s] them shudder. They don’t like to think of depriving dumb creatures of life, but they have no objections to eating meat. And they know someone must kill in order that others may eat.”20 It was a world far removed from the thrills of the World Series.

Schmidt’s final appearance in Boston came a little over a year before his death. In June 1951 he returned to take part in the Braves’ salute to the ’14 champs during the National League’s Diamond Jubilee commemoration. He died in Baltimore on September 4, 1952, after collapsing while inspecting cattle at the Union Stockyards. He weighed more than 240 pounds and for the previous five or six years he had been having trouble with his heart. Schmidt was 66 years old. Ownership of the family business passed to Schmidt’s son, Charles, who died in 1981.

Butch Schmidt was buried at the Druid Ridge Cemetery, in Pikesville, Maryland.

In 1981 Schmidt was elected to the Maryland State Athletic Hall of Fame. That day, a reporter from the Baltimore Sun interviewed Tommy Thomas, a Maryland baseball legend who had been a teammate of Schmidt’s on the Orioles. Thomas remembered Schmidt as “just a damn fine player. Not sensational, but when the game was over, you always realized he had done something to help the team win.” And of Schmidt’s giving up the sport to devote his life to the meat market, Thomas said, “He just decided there was a better future for him there than in baseball.”21

Indeed, for Schmidt it seems to have been the right decision.

This biography is included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

My sincerest appreciation to SABR member Bill Mortell for his diligent genealogical research.

In addition to the sources cited, the author also consulted citypaper.com/news/story.asp?id=13918 (Baltimore City Paper, August 1, 2007)

Notes

1 John J. Ward: “ ‘Butch’ Schmidt, the Player-Worker,” Baseball Magazine, March 1916.

2 Ibid.

3 Sporting Life, February 5, 1916.

4 John J. Ward: “ ‘Butch’ Schmidt, the Player-Worker.”

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Wm. A. Phelon, “Sidelights on the New World’s Champions,” Baseball Magazine, February 1915. All subsequent quotes in the paragraph are from the article.

8 Myers never played for Rochester. Instead, he jumped to the Federal League’s Brooklyn team.

9 Boston Daily Globe, May 5, 1915.

10 Wm. A Phelon, “Sidelights on the New World’s Champions.”

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Baltimore Sun, September 5, 1952.

15 Sporting Life, February 5, 1916.

16 Ibid.

17 Sporting Life, January 6, 1917.

18 Sporting Life, February 3, 1917.

19 John J. Ward: “‘Butch’ Schmidt, the Player-Worker.”

20 Ibid.

21 Baltimore Sun, January 19, 1981.

Full Name

Charles John Schmidt

Born

July 19, 1886 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

Died

September 4, 1952 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.