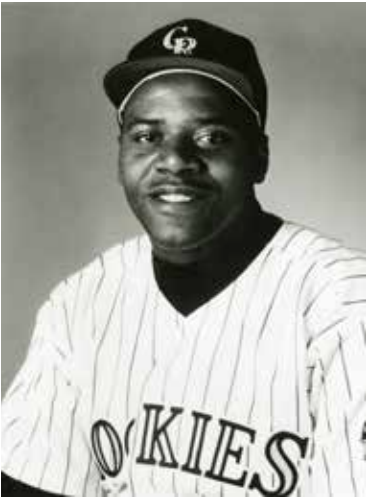

Charlie Hayes

Third baseman Charlie Hayes was a solid journeyman. He played for seven teams over 14 years in the majors from 1988 through 2001. He had a good glove, a strong arm, and some pop in his bat. His best offensive numbers came in 1993 with an expansion club, the Colorado Rockies. Yet the moment for which he is best remembered came as he caught a foul pop to end the 1996 World Series.

Third baseman Charlie Hayes was a solid journeyman. He played for seven teams over 14 years in the majors from 1988 through 2001. He had a good glove, a strong arm, and some pop in his bat. His best offensive numbers came in 1993 with an expansion club, the Colorado Rockies. Yet the moment for which he is best remembered came as he caught a foul pop to end the 1996 World Series.

“I walk around and people still talk about that catch,” said Hayes during a visit to Yankee Stadium on Old-Timers’ Day 2013. “You’d think it would go away, but it hasn’t happened yet. I’m honored to be part of that. Just being part of the Yankee tradition is unbelievable, and this is proof.”1

Charles Dewayne Hayes was born on May 29, 1965, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He was the oldest of four children; his younger sisters were named Sabrina, Selina, and Bernilla. Their mother, Lutherea Hayes, was a cook in a nightclub. She was the one raising all four children; little Charlie was only 4 years old when his father died.2

Young Hayes’ sports hero was the great basketball player Julius Erving. “I always wanted to play basketball, but baseball came easier,” he said in 1993.3 The previous year he noted, “It was baseball that worked out for me. My mother worked hard. But she helped me reach my dream. If I needed, say, a new glove, she went without things so I could have it.”4

At age 12 in 1977, Hayes was a member of the Hub City team from Hattiesburg that represented the South Region of the United States in the Little League World Series.5 Hattiesburg, with Hayes on the mound, lost to El Cajon, California, in the first round. It was a competitive game; the final score was 3-1. Hayes went all six innings, striking out six and allowing four hits while giving up a solo homer; runs also scored on his balk and wild pitch.6 Hattiesburg eventually won the consolation bracket.

Hayes attended Forrest County Agricultural High School in Brooklyn, Mississippi. He was a two-sport star there; one may infer the other was basketball. In baseball, however, his feats led the school to retire his number.7 As a senior, he hit .530 with 14 doubles and 4 homers; he was also 8-3 as a pitcher. He was named to Mississippi’s All-State high school team, a squad that also included Marcus Lawton, who played 10 games for the Yankees in 1989 (younger brother Matt Lawton played in the majors from 1995 through 2006).8

The Jackson Clarion-Ledger noted that Baseball America had ranked Hayes among the top 25 high-school players in the nation. “He’s probably the best athlete ever to come through Forrest County AHS,” said his coach, Glen Dewease. “A lot of pro scouts are looking at him as a third baseman. If he really wants (a pro career), he can go.” One scout said, “Most everybody likes him as a third baseman or possible outfielder. He’s got good running speed and enough arm strength to play either spot. The big question is his bat, whether he’ll hit. But his other tools measure up to major-league standards. He’s got a chance of being drafted high.”9

Indeed, the San Francisco Giants selected Hayes with their fourth-round pick in the June 1983 amateur draft. In the Pioneer Rookie League, he played both third base and outfield (he never pitched in a pro game).

Around that time, Hayes got married. He and his wife, Gelinda, had three sons: Charles Jr., Tyree, and Ke’Bryan. Charles Jr. grew to 6-feet-4 and 290 pounds — he preferred football to baseball.10 The two younger brothers both became pro baseball players. Tyree was an eighth-round draft pick of the Tampa Bay Devil Rays in 2006. Ke’Bryan — whom Gelinda was expecting during the 1996 World Series — was a first-round pick of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 2015.

It took Charlie Hayes six seasons to climb the ladder to the majors. He wanted to give up baseball during the 1984 season, come home to Hattiesburg, and enroll in college — but his mother told him, “There are no quitters in this house.”11

Hayes represented Fresno in the California League’s 1985 All-Star Game. But as he recalled, “The turning point came when in 1987 I was sent back to Double A after spending spring training with the Triple-A team. I thought then there were other things I could do, and that it wasn’t too late to go to college. I was doubting myself. Jack Mull, my manager, said, ‘You’re too hard on yourself. You’re such a team player. Remember, sometimes you have to be selfish.’ And my mother said, ‘Give it your best shot. Something good will happen and other good things will follow.’”

“Jack Mull’s support — and my mother’s — helped me reach my dream. My mother matured me in a way that gave me that extra drive that I needed to make it.”12

Hayes had not shown much power in his first four pro seasons, hitting just 11 homers in total. With Shreveport of the Texas League in 1987, though, he hit 14 and had 75 RBIs while also breaking the .300 mark for the first time. He thus earned promotion to Triple-A Phoenix in 1988 and had another good year (.307-7-71), though he played more outfield than third base that season.

When rosters expanded in September 1988, Hayes got his first call-up. His big-league debut came in left field. Hayes got into six more games over the rest of the season, appearing twice more in left and once in right. After that, he played just once more as an outfielder in the majors, for two innings in 1999.

Hayes returned to Triple A to start the 1989 season. The Giants continued to experiment with him as an outfielder. He was called up briefly in early May as Matt Williams was optioned to Phoenix. He appeared in three games at third base before being sent back.

On June 18, 1989, Hayes became part of a five-player trade with the Philadelphia Phillies that sent Steve Bedrosian and Rick Parker to San Francisco. Philadelphia also received lefty pitchers Terry Mulholland and Dennis Cook. Hayes reported to the Phillies’ top farm club, Scranton/Wilkes-Barre, but at the end of the month Philadelphia brought him up after receiving glowing reports from special-assignment scout Jim Fregosi and Red Barons manager Bill Dancy.13 Hayes never played again in the minors.

Hall of Fame third baseman Mike Schmidt had retired near the end of May, stating that he could no longer live up to the high standards he had set for himself as a player.14 The Phillies tried outfielder Chris James at third for a little while. Then they used Randy Ready, a utilityman; Von Hayes, an outfielder/first baseman; and Steve Jeltz, a shortstop. Hayes got the job in large part because he was a true third baseman.

Shortly after the promotion, Philadelphia’s general manager, Lee Thomas, remarked, “Charlie has been a good hitter at every level in the minor leagues. If he can hit a little up here, he’ll be our third baseman. Defensively, he’s got soft hands and a better than average arm. So far, we’ve been very impressed.”15 Indeed, Hayes started 79 of the Phillies’ remaining games at third. His production with the bat was promising: 8 homers and 43 RBIs in 315 plate appearances, while batting .258.

Hayes made 11 errors in his first 23 games, including four in one game as the Phillies lost on July 15. Yet he was unfazed. “I heard some boos,” he said, “but my job is to play as best I can. Errors are part of the game. I was going hard and it just happened.”16 Manager Nick Leyva added, “He’s been pressing. I believe he’s a better fielder than he’s shown.”17 He wound up with 22 errors for the year and drew frequent criticism from Leyva.18

Hayes, who trimmed down from 223 pounds to 202 over the winter, remained the regular at third for the Phillies in 1990. “I think we’ve reached Charlie,” said Leyva not long before Opening Day. “I believe he is totally committed and that we are going to see a different player this year.”19 Hayes again hit .258 in 1990, but his power totals were rather modest: 10 homers and 57 RBIs in 141 starts. He did, however, cut his errors down to 20. One of them represented the only baserunner that Terry Mulholland allowed in his no-hitter at Veterans Stadium on August 15. Oddly enough, it was Rick Parker of the Giants who reached base as Hayes’ throw pulled John Kruk off the bag. Hayes atoned for it, however, by backhanding pinch-hitter Gary Carter’s liner to end the game.

Hayes slumped in 1991 and lost playing time. He started just 109 games and posted a batting line of .230-12-53. In late July, the Phillies recalled third baseman Dave Hollins from Scranton/Wilkes-Barre and gave him an audition as the starter, followed by an extended trial in September and October. Hayes bounced back at the plate toward the end of the season, but he could tell that his days in Philadelphia were numbered. He said, “All I can do now is hope that I played well enough down the stretch to convince somebody that I’m an everyday player.”20

Looking back in 2015, Hayes said, “I loved Philly. It was a tough situation for me, being the guy who was kind of the heir apparent to Mike Schmidt. But one thing that Philadelphia taught me was about being tough, being determined — a blue-collar work ethic.” He noted how that helped him in his work as a youth baseball coach. “I instill those things in all my kids. Always told them there were never any excuses. You just pick yourself up and try to get better every day.”

He added, “I’m sure there were probably some things I could have done better: dealing with the media, accepting failure. But there’s no doubt that Philadelphia made me the player I was.”21

The Yankees obtained Hayes for the first time in February 1992. He was the player to be named later in the trade that had sent pitcher Darrin Chapin to Philadelphia the previous month. Dave Hollins took over the Phillies’ third-base job in 1992 and had his most productive year; he was also a key member of the 1993 NL pennant-winners.

Hayes beat out Hensley Meulens at third base and had a nice year for New York in 1992: .257-18-66 in 142 games. He started 137 times at third and three times at first base, a position he played with some frequency later in his career. After the season ended, The Sporting News called him “the most pleasant surprise of the season for the Yankees. He was dependable defensively and productive offensively.”22

Nonetheless, the Yankees made Hayes available in the expansion draft that November, and Colorado selected him with the third pick overall. Yankees general manager Gene Michael admitted, “We gambled. I’d hoped they would take a young player, and Charlie would slip through.”23 Shortly after that, however, New York signed Wade Boggs as a free agent.

Hayes had expected to be a Yankee for the long term. At first, he was devastated by the move. Yet it became part of his ongoing learning experience in the majors. “I grew up a lot that day,” he said. “But instead of feeling sorry for myself, I started thinking like a Rockie. I just try to make the best of the situation. What baseball does is this: No matter how good you are, there’s no security. But I can control being mentally prepared to play; I can control giving 110 percent.”24

Hayes’ new team felt fortunate. “The Rockies believed from Day One of their existence that one of their best expansion-draft pickups was third baseman Charlie Hayes,” said STATS Inc.’s Scouting Report for 1994. “They were not disappointed, as Hayes — next to Andrés Galarraga — was Colorado’s most consistent player. He was everything the Rockies hoped he’d be, and more.”25

Mile High Stadium, where the Rockies played their first two seasons, was a hitters’ ballpark. It was particularly favorable for right-handed hitters like Galarraga, Dante Bichette — and Hayes, who posted the best offensive season of his career.26 He had a team-high 25 homers, 98 RBIs (tied with Galarraga for tops on the club), and a .305 batting average in 157 games. He also led the National League with 45 doubles. His home-away splits were notable, though: .338-17-66 at Mile High vs. .271-8-32 on the road.

Hayes remained the Rockies’ starting third baseman in 1994. Perhaps the most noteworthy thing from that season was visual. On June 25, pitcher Salomón Torres of San Francisco hit Hayes in the face with a pitch. It came right after Torres had opened the inning by hitting Galarraga in the left arm; Colorado manager Don Baylor had to restrain Hayes from charging the mound, and a brawl almost erupted. Hayes suffered a broken cheekbone and left the game, but missed only two games after that. When he returned to action, he experimented with a couple of kinds of clear mask attached to his helmet.27

Hayes’ power numbers dipped to 10 homers and 50 RBIs in 113 games during the strike-shortened season. His $3 million salary was more than Colorado found palatable, and so they did not tender him a contract.28 The Rockies turned third base over to Vinny Castilla, who gave them five big seasons in a row with the bat.

While spring training 1995 was conducted with replacement players, the Giants expressed interest in signing Hayes as a first baseman.29 But when the strike ended in April 1995, Hayes returned to Philadelphia, which moved Dave Hollins to first. Hayes was happier in Philadelphia the second time around. That June, Lee Thomas said, “Charlie has smiled more times in the last couple of weeks than he did in the couple years he was here before.”30 He had a good year (.276-11-85); The Sporting News remarked, “Hayes did what he usually does: drove in runs and played sound defense.”31

Even so, the Phillies — who had star prospect Scott Rolen ready to take over at third — had no interest in meeting Hayes’ wish for a two-year contract.32 Thus, he became a free agent again. The Pittsburgh Pirates signed him near the end of 1995.

Forrest County Agricultural High retired Hayes’ number 1 in February 1996. Not normally an emotional man, Hayes was greatly moved by the ceremony.33 It was an auspicious start to the season, but the Pirates were disappointing and began to turn over their roster toward the end of the summer. On August 30, the Yankees re-obtained Hayes for a player to be named later (Chris Corn, a pitcher who never reached the majors).

Wade Boggs was still New York’s starting third baseman in 1996, but the team wanted to platoon him. Manager Joe Torre had said that Boggs was tired and his bat was slow at times, and that Hayes was added to provide some power.34 Boggs felt slighted, but the depth proved valuable because he missed several games in September with back spasms.

“That team was a group of guys that came together,” said Hayes in 2013. “While there were a lot of superstars on that team, the biggest thing is that Joe Torre got everybody to make sacrifices. I remember one game where I wasn’t playing against a lefty, and thought I should’ve been. I walked out on the bench and I saw (Darryl) Strawberry to my left, Tim Raines to my right, and Tino (Martinez) behind me, and I said to myself, ‘What could you be complaining about? These guys here have done way more in this game than you have!’ From that day forward, I just approached every game like it was my last.”35

The Yankees played 15 games in the 1996 postseason, and Hayes appeared in 12 of them, starting six times. His best outing was in Game Four of the World Series at Atlanta, when he went 3-for-5 with an RBI.

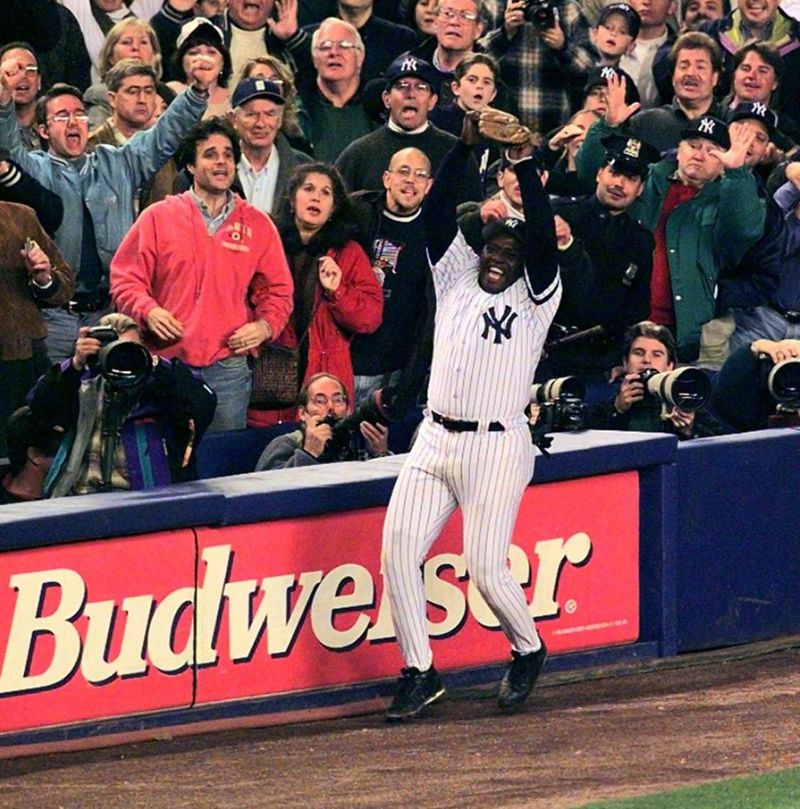

Three nights later, at Yankee Stadium, Hayes entered Game Six in the top of the seventh inning, replacing Boggs at third. He didn’t handle any chances until pesky Mark Lemke came to the plate with two outs in the ninth, the tying run on second base, and the go-ahead run on first. The count ran full, and Lemke popped John Wetteland’s next pitch toward the visitors’ dugout. Hayes had a chance to make the play, but an Atlanta batboy got in his way. Hayes got clear and continued his pursuit of the ball, but it was out of reach as he tumbled into the dugout. Tim McCarver, calling the game for Fox TV, noted that interference could have been called.36 Had the Yankees lost that game and the Series, that batboy could have become as notorious as Cubs fan Steve Bartman did for his action in the 2003 playoffs.

On the pitch after that, though, Lemke lifted another little foul pop. This one stayed in play, and as it settled into Hayes’ glove, the Yankees were champions of baseball for the first time in 18 years.

On the pitch after that, though, Lemke lifted another little foul pop. This one stayed in play, and as it settled into Hayes’ glove, the Yankees were champions of baseball for the first time in 18 years.

In retrospect, Hayes offered another intriguing detail — he got hurt on Lemke’s first foul. “I think I broke my finger and I didn’t even know it until after the game,” he said. “So it would have been very interesting to see what would have happened if that ball was hit on the ground and I would have had to throw it to first base.”37 Whatever happened to that ball? It and the glove Hayes used that night were sold at auction in 2014.

Hayes and Boggs remained in a platoon at third for Yankees in 1997, which didn’t make either man happy. Hayes played about 55 percent of the innings there and Boggs played 42 percent. For about a month, from early July through early August, Boggs served mainly as the team’s designated hitter. It came shortly after he proclaimed himself “mentally shot” and said “it’ll help the team more if Charlie plays.”38 Hayes started four of the five games in the AL Division Series, which New York lost to the Cleveland Indians.

The major leagues then were about to add two more franchises (Arizona and Tampa Bay). Thus, the possibility arose that Hayes could have been chosen for the second time in an expansion draft. Before that draft, however, New York sent him (plus cash) back to his original organization, the Giants. “He’s a very good defensive third baseman and can play first base,” said Dusty Baker, then San Francisco’s manager. “Plus, he’s a clutch hitter and run-producer.”39 Replacing Hayes and Boggs at third for the Yankees was Scott Brosius, a key member of the teams that won three straight World Series and nearly a fourth.

Meanwhile, during 1998 and 1999, Hayes backed up Bill Mueller at third and J.T. Snow at first. In 1998, Snow — a switch-hitter for his first several years in the majors — had fallen off so badly swinging from the right side that Baker began to platoon him with Hayes.40 From 1999 on, Snow batted only left-handed.

In the fall of 1999 Hayes became a free agent again; the New York Mets signed him in January 2000. That March he received the troubling news that his beloved mother had been diagnosed with breast cancer. Hayes experienced heart irregularities and cited the emotional stress, but an EKG showed that he was OK.41

The Mets released Hayes on March 20, but two days later, the Milwaukee Brewers picked him up. He spent the 2000 season as a reserve corner infielder, starting 48 games at third behind José Hernández and 46 at first (Richie Sexson got the most action there). He hit the last of his 144 major-league homers on September 11 off Rich Rodriguez of the Mets.

Entering free agency once more, Hayes signed with the Houston Astros in January 2001. He made the team but had to leave on April 27 to be with his ailing mother in her final days. The Astros placed him on the restricted list, which enabled the team to call up a replacement (Keith Ginter) during the time of bereavement. Hayes was activated on May 8.42

Serving mainly as a pinch-hitter, the veteran got into 31 games for Houston. He hit .200-0-4 and was released on July 9. He thereupon retired.

Hayes then got into coaching youth baseball in the Houston area. Two former pros named Ray and Robert DeLeon had a baseball school called Home Plate Inc. in The Woodlands, a community in the Houston area. The DeLeons sold it in 2002 and started a bigger facility called Future Baseball Stars Academy. Hayes was one of the instructors, along with his good friend and former teammate with the Phillies, Ron Jones.

Jones approached Hayes in 2005 about starting their own baseball school. Initially, Hayes was reluctant to get involved, but the tight bond between the two men convinced him to go ahead. They opened the Big League Baseball Academy in Tomball, Texas (also outside of Houston).43 They worked together until Jones died suddenly at home in June 2006. One of the big clues that something was wrong was the lack of response from Jones when Tyree Hayes was drafted. It was out of character for him not even to call.

Hayes could not bring himself to go back to the academy for months. He initially wanted to close it down after the loss of his best friend. Yet he heard from his wife that because Jones talked him into doing it, he should keep it open — which it still is (as of 2018).44

Tyree Hayes pitched through 2011 in the minors with the Tampa Bay and Cincinnati chains. He played in the independent Frontier League in 2012. Ke’Bryan Hayes began his fourth pro season in 2018. The promising prospect played for the Altoona Curve in the Double-A Eastern League.

Charlie Hayes returned to pro ball in 2017 as bench coach of the Lehigh Valley IronPigs in the Triple-A International League. The IronPigs became the Phillies’ top farm team in 2008. “The only difference is the kids here are older than those [at my academy],” said Hayes. “I’m still teaching kids the fundamentals of the game, stuff I learned along the way.”45 As the 2018 season began, he was serving as a rookie-ball coach for the Gulf Coast League Phillies.

Last revised: December 1, 2018

This biography appeared in “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

bigleaguebaseballacademy.com.

YouTube.com.

ha.com (Heritage Auctions).

Notes

1 Lou DiPietro, “Almost 20 Years Later, Charlie Hayes Still Fondly Remembered for ‘The Catch,’” Yesnetwork.com, July 12, 2013.

2 “Lutherea Hayes,” Hattiesburg American, May 4, 2001: 15. Owen Canfield, “Always Worth Singling Out,” Hartford Courant, November 11, 1992. José de Jesús Ortiz, “Astros’ Hayes Feels Void After Mother’s Death,” Houston Chronicle, May 13, 2001.

3 Tracy Ringolsby, “Colorado Rockies,” The Sporting News, January 11, 1993: 31.

4 Canfield, “Always Worth Singling Out.”

5 Tim Doherty, “Aggies Pay Tribute to Hayes,” Hattiesburg American, February 13, 1996: 11.

6 “Hattiesburg Out in Series Play,” Monroe (Louisiana) News-Star, August 24, 1977: 13. “Sports Wire Notes,” Galveston Daily News, August 24, 1977: 6.

7 Doherty, “Aggies Pay Tribute to Hayes.”

8 “All-State Team Heralds Year of Skilled Catchers,” Jackson Clarion-Ledger, June 5, 1983: 48.

9 Ibid.

10 Jerry Crasnick, “Charlie Hayes, Mike Cameron Basking in the Success of Their Sons,” ESPN.com, June 8, 2015.

11 de Jesús Ortiz, “Astros’ Hayes Feels Void After Mother’s Death.”

12 Canfield, “Always Worth Singling Out.”

13 “N.L. East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1989: 39.

14 “Schmidt Retires after 17 Years and 548 Homers,” New York Times, May 30, 1989.

15 “N.L. East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1989: 30.

16 “Old Man Evans Climbs Past Duke on Homer List,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1989: 27.

17 “N.L. East: Phillies,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1989: 22.

18 “Dickie Thon Doesn’t Want ‘To Make a Mistake,’” The Sporting News, April 2, 1990: 37.

19 Bill Brown, “Will 1990 Campaign Be a Repeat of 1989?” The Sporting News, April 1, 1990: 28.

20 Bill Brown, “Philadelphia Phillies,” The Sporting News, November 4, 1991: 16.

21 Paul Hagen, “Hayes Fond of Philly, Friendship with Jones,” MLB.com, August 28, 2015.

22 Jack O’Connell, “New York Yankees,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1992: 19.

23 Jack O’Connell, “New York Yankees,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1992: 36.

24 William C. Rhoden, “Yankees Should Look to Their Journeyman, Hayes, as an Example,” New York Times, July 28, 1997.

25 John Dewan and Don Zminda, editors, The Scouting Report, 1994 (New York: HarperCollins Publishers: 1994), 433.

26 John Dewan and Don Zminda, editors, STATS 1994 Baseball Scorecard (New York: HarperCollins Publishers: 1994), 45.

27 “Controversy Follows Torres to the Mound,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City), June 26, 1994. Dan Gutman and Tim McCarver, The Way Baseball Works (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 37. Uni-watch.com shows pictures of Hayes in his different masks.

28 Tracy Ringolsby, “Colorado Rockies,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1994: 37. Tracy Ringolsby, “Colorado Rockies,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1995: 36.

29 Bob Nightengale, “Around the bases,” The Sporting News, March 20, 1995: 14.

30 Jon Heyman, “Following the Phillies’ Formula,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1995: 16.

31 George A. King III, “Philadelphia Phillies,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1995: 20.

32 George A. King III, “Philadelphia Phillies,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1995: 43.

33 Doherty, “Aggies Pay Tribute to Hayes.”

34 Jack Curry, “Boggs Feels Slighted as the Yankees Acquire Hayes,” New York Times, August 31, 1996.

35 DiPietro, “Almost 20 Years Later, Charlie Hayes Still Fondly Remembered for ‘The Catch.’”

36 A similar play took place in a game between the New York Mets and Milwaukee Brewers on June 1, 2017. A Brewers batboy got in the way of Mets third baseman Wilmer Flores as Flores tried to catch a bunt that had been popped up in foul territory. An umpire initially called batter Chase Anderson out, but after the umpires conferred, they reversed the call because it was deemed to be unintentional interference. See Rule 6.01(d) in the Major League Baseball rulebook.

37 Peter Schwartz, “Remembering The 1996 Yankees: Second Time Was the Charm For Hayes,” CBS New York website (newyork.cbslocal.com), July 22, 2016.

38 John Giannone, “Wade Wants Ride Out of Town,” New York Daily News, July 6, 1997.

39 John Shea, “San Francisco Giants,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1997: 28.

40 Henry Schulman, “Snow Makes a Choice: He’ll Try to Hit Lefthanded,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1998: 63.

41 David Lennon and Marty Noble, “Hayes OK After Tests, Says Stress to Blame,” Newsday, March 14, 2000.

42 “News and Notes,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 8, 2001: 25.

43 Hagen, “Hayes Fond of Philly, Friendship with Jones.”

44 Ibid.

45 Tom Housenick, “IronPigs Bench Coach Hayes Just One of the Boys,” The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), September 3, 2017.

Full Name

Charles Dewayne Hayes

Born

May 29, 1965 at Hattiesburg, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.