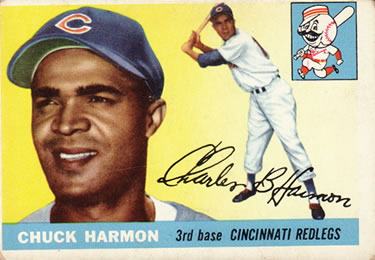

Chuck Harmon

The first African-American player for the Cincinnati Reds, Charles Byron “Chuck” Harmon, was born on April 23, 1924, in Washington, Indiana. The 10th of 12 children born to Sherman and Rosa Harmon, he attended elementary school in a one-room schoolhouse where his father taught. As a child, he listened to baseball games on the family’s Philco radio, mostly those of the St. Louis Cardinals, whose signal from KMOX could be heard nationwide. Though baseball was one of many sports he enjoyed playing, as an African-American, he never dreamed of playing in the big leagues. “There was nothing to dream about,” Harmon said. “We couldn’t play.”1

The first African-American player for the Cincinnati Reds, Charles Byron “Chuck” Harmon, was born on April 23, 1924, in Washington, Indiana. The 10th of 12 children born to Sherman and Rosa Harmon, he attended elementary school in a one-room schoolhouse where his father taught. As a child, he listened to baseball games on the family’s Philco radio, mostly those of the St. Louis Cardinals, whose signal from KMOX could be heard nationwide. Though baseball was one of many sports he enjoyed playing, as an African-American, he never dreamed of playing in the big leagues. “There was nothing to dream about,” Harmon said. “We couldn’t play.”1

Young Harmon excelled first in basketball. He helped lead the Washington High School Hatchets to back-to-back Indiana state basketball championships in 1941 and 1942, scoring nine points in the 1941 title game and nine points in the 1942 semifinal game.

Harmon’s basketball skills earned him a scholarship to the University of Toledo, where he was an All-American player. In 1943 Harmon scored six points in the Rockets’ 48-27 loss to St. John’s in the National Invitation Tournament (NIT) Finals at Madison Square Garden. Perhaps more significantly, before the title game, Harmon met Babe Ruth and shook the hand of the Sultan of Swat.

But by the end of his freshman year, men of all ages were expected to serve their country, and Harmon left school to serve in the Navy during World War II. Assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Station near Chicago, Harmon joined the black baseball team. He roomed with Larry Doby, who would later be the second African-American to play major-league baseball in the modern era and the first in the American League, signing with the Cleveland Indians in 1947.

Harmon spent the war stateside, and after a three-year hitch, he returned to the University of Toledo to play basketball and baseball.

In the summer of 1947, Harmon needed money to meet college and living expenses. But he also wanted to maintain his NCAA eligibility, so he signed with the Indianapolis Clowns to play baseball under the name “Charlie Fine.” Harmon had grown up watching the Clowns and idolized the team.

“Four games, four days on a bus,” Harmon said about his short stint in the Negro Leagues. “Goose [Tatum, who played with the Harlem Globetrotters] took me under his wing. He liked me because he knew I played basketball. Goose is the one who gave me the (alias) Charlie Fine. That’s the name I played under. Goose didn’t want my college eligibility to be affected.”2

Arriving home from the weekend road trip, Harmon had a telegram from the Toledo athletic director, who had found him a summer job on campus. His Negro League career was over practically before it began. But within a month he was signed to a minor-league contract by the St. Louis Browns (today’s Baltimore Orioles). Assigned to the Browns’ Gloversville-Johnstown team in upstate New York in 1947, he played 54 games in the outfield and batted .270.

Even more important to Harmon than the day he began playing pro ball was the day he met Daurel Pearl Woodley, a student at nearby Syracuse University. On December 29, 1947, they married in Gloversville. “Marrying her,” Harmon said, “was my greatest accomplishment.”3

The couple had three children — Charlene, Chuck Jr., and Cheryl. They were married for 62 years until Pearl passed away from cancer in 2009.

Back in Toledo, Harmon co-captained the university’s basketball team and was the second-leading scorer in the 1947-48 and 1948-49 seasons. Prior to his signing with the Browns, which ended his collegiate baseball eligibility, he also earned three varsity letters in baseball.

In 1948 Harmon played baseball with the independent General Electric team out of Fort Wayne, Indiana, then returned to Gloversville in 1949. Later that summer the Browns sent him to the Olean, New York, team in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League, where he batted .351 in 31 games. It was the first of five consecutive seasons in the minors that Harmon batted .300-plus. He remained with Olean for the next two seasons. In 1951, he hit .375 while leading the league with 143 RBIs, as the team won the pennant.

Despite his hot hitting, Harmon was not getting the call to the majors, so he also pursued a career in professional basketball. He was one of the final players cut by first-year coach Red Auerbach from the 1951 Boston Celtics. Had he made that team, he would have been one of the first African-Americans in the NBA. He did, however, become the first African-American to coach in integrated professional basketball, leading the Eastern League’s Utica, New York, team as a player/coach.

Harmon returned his focus to baseball in 1952, when he was acquired by the Cincinnati Reds. He spent two more years in the minors, including the 1952 season with the Burlington (Iowa) Flints of the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League, batting .319 in 124 games. In 1953, he was promoted to the AA Tulsa Oilers, becoming the first African-American player in the history of the Texas League’s Tulsa franchise, and batted .311 with 83 RBIs, 14 home runs, and 25 stolen bases in 143 games.

That winter, the Reds sent Harmon to Puerto Rico for winter ball, where Harmon was second in the league in hitting, beating out future home-run king Hank Aaron.

This performance was enough to be invited to Cincinnati’s spring training in 1954, and in April Harmon made the Reds’ roster. On April 17, 1954, at Milwaukee’s County Stadium in the top of the seventh inning, manager Birdie Tebbetts needed a pinch-hitter for pitcher Corky Valentine, and Harmon got the call. His first major-league at-bat ended in a popout, but began an era for the Cincinnati Reds. Harmon was the first African-American to play for the Reds. “It was another day at the beach, I guess,” Harmon said. “People ask me the same old thing, ‘Did you think you would make history?’ I tell them when you’re born, you’re history. You don’t realize when you’re actually making history.”4

But he was not the only player to make history for the team that day. Batting just before Harmon in the same game, Nino Escalera, a Puerto Rican of African descent, became the first black player for Cincinnati. When asked who deserved credit for being the first player of color, Harmon said, “I was the first African-American; Nino was the first black. I don’t know what difference it makes, but for history’s sake, they might as well get it right.”5

Also for history’s sake, Harmon followed the advice and example of those who had come before him. Manager Tebbetts counseled him to remain calm if he heard insults from the fans or opposing players: “Walk away; fold your arms. If not, you’ll get beat up and blamed for starting it.”6

On April 25, 1954, two days after his 30th birthday, Harmon got his first hit, a single in the first inning off the Cubs’ Howie Pollet, back home at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. Later in that game he doubled, scored on an error, and walked. For the season, Harmon played three games at first base and 67 games at third base, while batting .238 in 94 games.

His major-league numbers weren’t as good as in the Texas League, but were good enough to return to Cincinnati in 1955. That year he was a true utility player, spending time at first base, third base, and in the outfield. He earned his nickname “The Glove” because he could play any position, and had a special glove for each one.

On July 23, 1955, at the Polo Grounds, Giants pitcher Jim Hearn was two outs away from a no-hitter when Harmon came up to bat in the ninth inning. His single broke up the no-hitter, and Harmon received a death threat in the form of a letter from a New York fan. Nothing came of it, but the incident was indicative of the continuing issues players of color faced. “If you worried about how you were being treated or going to be treated, you don’t need to be there,” Harmon said. “You have to play the game and do all the little extra things. You don’t have time to wonder if someone will look at you cross-eyed or say something to you. It was enough to worry about that baseball coming at you, or someone sliding into you. There were too many other things to worry about.”7

This attitude served him, and other players, well during that time. “If you had put some of the other guys in there, blacks would have never made it to the majors,” said Harmon. “That’s why they took Jackie [Robinson]. Jackie was an officer in the military. He was an All-American at UCLA. That’s why I was picked. I served in the military. I went to college. Playing for Toledo in the NIT, which at the time was the biggest basketball tournament in the country, people knew my name.” He added, “You had people in the stands hollering things at you, but I didn’t pay it any attention. All I wanted to do was hit the ball further. I’d take it out on the ball.”8

And take it out on the ball he did, batting .253 in 1955 with five home runs and 28 RBIs in 96 games.

Harmon began the 1956 season in Cincinnati, but after four unproductive at-bats in 13 games, he was traded to the Cardinals in May. He didn’t fare much better in St. Louis, and after going hitless in 20 games, finished the season in AAA Omaha.

The 1957 season found Harmon again in a Cardinals uniform, but he was traded in May, this time to the Philadelphia Phillies. There he roved the infield and outfield, finishing the year with a .258 batting average. On September 15, 1957, he played his final major-league game at the site of his first, appearing as a pinch-runner at County Stadium and scoring his final run on a double play. When in 1958 he was assigned to the Phillies’ AAA team, the Miami Marlins, his major-league career was finished after four years, 289 games, and a .238 average. Harmon spent the next four years with the Marlins, St. Paul Saints, Charleston Senators, Salt Lake City Bees, and Hawaii Islanders, before retiring from the game in 1961 at the age of 37.

The 1957 season found Harmon again in a Cardinals uniform, but he was traded in May, this time to the Philadelphia Phillies. There he roved the infield and outfield, finishing the year with a .258 batting average. On September 15, 1957, he played his final major-league game at the site of his first, appearing as a pinch-runner at County Stadium and scoring his final run on a double play. When in 1958 he was assigned to the Phillies’ AAA team, the Miami Marlins, his major-league career was finished after four years, 289 games, and a .238 average. Harmon spent the next four years with the Marlins, St. Paul Saints, Charleston Senators, Salt Lake City Bees, and Hawaii Islanders, before retiring from the game in 1961 at the age of 37.

Harmon remained in baseball for a time, working as a scout for the Atlanta Braves and the Cleveland Indians, as well as for basketball’s Indiana Pacers. He later worked in sales for MacGregor Sporting Goods, before spending 24 years as the deputy clerk/administrative assistant of the Hamilton County, Ohio, First District Court of Appeals in Cincinnati.

In 1977, the first of many honors were bestowed upon Harmon when he was inducted into the inaugural class of the University of Toledo Athletic Hall of Fame. He was also inducted into the Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame in 1995. In 1997, a suburban Cincinnati street was renamed “Chuck Harmon Way.” On March 28, 2003, Harmon threw out the first pitch ever at the new Great American Ball Park in Cincinnati. The next year, in honor of the 50th anniversary of his debut with Cincinnati, the Reds held “Chuck Harmon Recognition Night,” where they unveiled a historic plaque in tribute to his achievement. In 2014, he was inducted into the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame as the recipient of the Powel Crosley Jr. Award. And in 2015, just before Cincinnati hosted the All-Star Game, a statue of Harmon was installed at the Reds’ urban youth baseball academy in Roselawn, Ohio.

With the passing of Monte Irvin in January 2016, Harmon became the oldest living African-American to play in the major leagues. He was a beloved member of the Cincinnati Reds family and he still attended their games when he could.

“I just wanted to play baseball,” Harmon said. “If the way I conducted myself on the field benefited others who came after me, then it was all worth it.”9

Harmon died at the age of 94 on March 19, 2019.

Sources

Besides the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted the following:

Cava, Pete. “Charles Harmon,” The Encyclopedia of Indiana-Born Major League Baseball Players, http://www.indbaseballhalloffame.org/inductees/inductee-charles-harmon/, accessed February 20, 2017.

“Chuck Harmon,” http://library.cincymuseum.org/aag/bio/harmon.html, accessed February 20, 2017.

Clark, Dave. “Chuck Harmon to Receive Powel Crosley, Jr. Award,” Cincinnati.com, http://www.cincinnati.com/story/redsblog/2014/04/13/chuck-harmon-to-receive-powel-crosley-award/7667759/, accessed February 20, 2017.

Hsu, Spencer S. “Over Generations, Breaking Baseball Barriers,” Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/over-generations-breaking-baseball-barriers/2011/06/04/AGK8s6IH_story.html, accessed February 20, 2017.

“IHSAA Boys Basketball State Champions,” Indiana High School Athletic Association, http://www.ihsaa.org/Sports/Boys/Basketball/StateChampions/tabid/124/Default.aspx, accessed February 20, 2017.

“Chuck Harmon’s Lasting Legacy,” Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame & Museum, http://cincinnati.reds.mlb.com/cin/hof/article.jsp?ymd=20120217&content_id=26729278&fext=.jsp&c_id=cin, accessed February 20, 2017.

“Chuck Harmon,” Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/harmon.html, accessed February 20, 2017.

“Indiana Boys Basketball: Year-by-Year Capsules (1940-49),” Northwest Indiana Times, http://www.nwitimes.com/sports/high-school/indiana/indiana-boys-basketball-year-by-year-capsules/article_f28b5704-03c3-5d4f-b02c-770b15b73da4.html, accessed February 20, 2017.

Petracco, Ben. “Chuck Harmon Statue to be Unveiled at Urban Youth Baseball Academy,” wlwt.com, http://www.wlwt.com/article/chuck-harmon-statue-to-be-unveiled-at-urban-youth-baseball-academy/3555127, accessed February 20, 2017.

Swaine, Rick. Black Stars Who Made Baseball Whole: The Jackie Robinson Generation in the Major Leagues (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2005), 244-245.

Wheeler, Lonnie and Baskin, John. “In the Shadows: Cincinnati’s Black Baseball Players,” Queen City Heritage, Vol. 46, No. 2, Summer 1988.

Notes

1 Marty Pieratt, First Black Red (Bloomington, Indiana: Authorhouse, 2014), 38.

2 John Erardi, “Chuck Harmon: Riding with the Clowns, First in the Reds,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 4, 1999.

3 MLB.com, “Chuck Harmon’s Lasting Legacy,” February 17, 2012.

4 Mark Sheldon, “Humble Harmon Key Figure in Reds History,” MLB.com, http://m.mlb.com/news/article/28513304/ , accessed February 20, 2017.

5 Ibid.

6 Pieratt, 187.

7 Sheldon, “Humble Harmon.”

8 “Trailblazer Rockets Harmon Made History,” Toledo Blade, February 25, 2004.

9 Ibid.

Full Name

Charles Byron Harmon

Born

April 23, 1924 at Washington, IN (USA)

Died

March 19, 2019 at Golf Manor, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.