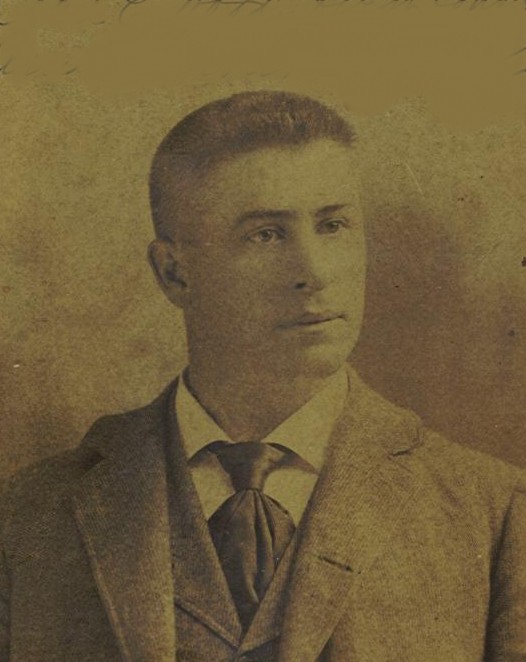

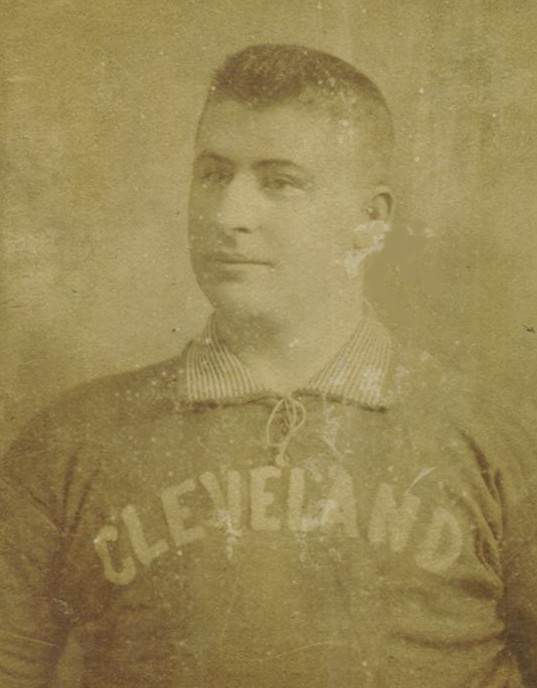

Cupid Childs

Cupid Childs was one of the best hitting major league second basemen during the late nineteenth century, not to mention a better-than-average fielder who possessed great range on the diamond. Only four other second basemen in the history of major league baseball have averaged more total chances per game than Childs. His all-around outstanding play made him an integral part of the great Cleveland Spiders teams of the 1890s.

Cupid Childs was one of the best hitting major league second basemen during the late nineteenth century, not to mention a better-than-average fielder who possessed great range on the diamond. Only four other second basemen in the history of major league baseball have averaged more total chances per game than Childs. His all-around outstanding play made him an integral part of the great Cleveland Spiders teams of the 1890s.

A natural middle infielder, Childs threw right-handed and batted left-handed. He played shortstop during his early years in the minors but eventually settled in at the keystone position for the remainder of his career. Childs, who seldom struck out, was a great contact hitter with an excellent batting eye. In his prime, he batted anywhere from first to fourth in the batting order. His best years in the majors produced batting averages of .345, .317, .326, .353, .355 and .338. Childs’ lifetime major league on-base percentage of .416 is higher than every second baseman in the Hall of Fame except Rogers Hornsby and Eddie Collins. His .306 lifetime batting average is higher than twelve of the second basemen who have already been inducted into the Hall. Childs scored over one hundred runs in a season seven times and reached double figures in triples five years in a row. However, for some reason the Hall of Fame Veterans Committee continually overlooks this talented multi-tooled player when it comes time to vote in new inductees. It seems that for now, Cupid’s arrow has missed its mark in Cooperstown.

Clarence Lemuel “Cupid” Childs was born to Singleton and Caroline Childs near Sunderlandville in Calvert County, Maryland, on August 8, 1867. Singleton Childs was a planter and farmer. According to the 1860 census, the Childs’ farm was valued at one thousand dollars. The 1870 census notes that Singleton and Caroline had 11 children living at home. Sadly, Singleton Childs died a few years after Clarence was born. At this time Mrs. Childs moved her large family to Baltimore City. While growing up in Baltimore, Cupid learned to play baseball on the local sandlots. Clarence eventually grew to 5’8″ and weighed a solid 185 pounds. In later years, his playing weight was listed at 192 pounds. It’s safe to assume that his resemblance to the fictional matchmaker was the reason for his cherubic nickname. He is also referred to in various newspaper accounts as “Fats,” “Fatty,” “Paca,” and even “The Dumpling.”

Childs’ obituary notes that he first played organized baseball in 1883 when he was sixteen years old for Durham in the North Carolina State League. According to the obituary, he was paid four dollars a week, and the team paid his room and board. Not much is known about Childs’ baseball career at this time. By May of 1885 Childs was playing shortstop for the very talented Monumental team in Baltimore. The Monumentals were playing in the Maryland Amateur Association in 1885. Future major league pitcher Frank Foreman pitched for the Woodberry team in the league that same year. At this time, Cupid Childs was living at 77 South Gilmore Street in Baltimore. His occupation is listed as can-maker in the 1885 Baltimore City Directory.

Childs started out the following season playing for the Baltimore Harlems semi pro team. By June of 1886, Childs had moved on and was playing shortstop with Petersburg in the Virginia State League. He played for Petersburg from June 25 to August 11. He left the Petersburg team and signed on with Scranton of the Pennsylvania State League for the rest of the 1886 season. He played in 24 games at shortstop for Scranton from August 17 to September 30. His final statistics for the 1886 Pennsylvania State League season were 27 hits, 6 doubles, 1 triple, 1 home run, 8 stolen bases and a .267 batting average.

Childs began the 1887 season with Johnstown of the Pennsylvania State League. He played with Johnstown from May 7 to July 4, when the Johnstown team folded. He then signed on with the Allentown team of the same league.

The Allentown Chronicle and News of July 7, 1887, observed: “The Allentown nine has secured Childs, the second baseman of the disbanded Johnstown club. Childs is a good hitter and a splendid baseman, and will prove a strong addition to the team.”

An article in the same paper on July 12 mentions Childs coming through with a clutch triple in a 14-8 Allentown victory over the Bradford team: “Then Childs picked up the stick and drove the ball to right field for three bases sending home Beatin and O’Brien which tied the score and caused such yelling that several boards back of the catcher split.”

Childs was with Allentown from July 8 to July 15, 1887, when the team dropped out of the league. Childs appeared in a total of 38 games during the 1887 Pennsylvania State League season. He had 69 hits, 7 doubles, 6 triples, 2 home runs and 14 stolen bases, finishing the year with a .373 batting average.

On August 4, Cupid signed with the Shamokin team of the Central Pennsylvania League. He played second base for the team until a broken collarbone ended his season on September 19, 1887. The Shamokin team went on to win the league championship.

In 1888, Childs signed with baseball pioneer Harry Wright‘s Philadelphia Quakers of the National League. He made his major league debut on April 23 against Boston and future Hall of Fame pitcher John Clarkson in Philadelphia. Childs went hitless at the plate that day. In the field, he played second base and handled six chances with one error while turning one double play. Clarkson pitched a complete game that day beating the Philadelphia team by the score of 3-1. The Quakers managed only six hits off Clarkson. Cupid Childs appeared briefly in the next game and then was released from the Philadelphia team. The Philadelphia Inquirer explained Childs’ pending release: “Childs and Hallman are good players but they lack experience and that is worth a great deal in this league.”

In June of 1888, Childs traveled out to Kalamazoo, Michigan, to try out for that city’s local professional baseball team. The Chicago Tribune of March 25, 1900, described Childs’ audition with the Kalamazoo team of the Tri-State League. The article is mistaken about Kalamazoo’s being Childs’ first professional team, but the story is an amusing look at how Childs was perceived by his peers:

“CHILDS’ DEBUT AS A BALL PLAYER

He Wears Divided Skirts for a Uniform

at His First Practice.

The Grand Rapids (Mich.) Democrat gives the following story of Cupid Child’s debut

in professional baseball:

“Childs is the most curiously built man in the baseball business: he is about as wide as he is long and weighs about as much as Jeffries, yet there are few men in the league who can get over the ground faster than the ‘dumpling.’ He started in the business as a professional with the Kalamazoo club in the Tristate league in 1888 and his work was so good that year that he graduated into fast company, where he has been ever since. When he reported to the Kalamazoo club he came in on a ‘side-door Pullman’ and presented himself to the management of the ‘Celery Eaters’ and asked for a trial. The manager thought he was joking after looking at his short length and broad girth, telling him he would make a better fat man in a side show than a ball player. Showing them he was anxious for a trial he was told to go to the grounds and practice with the rest of the team. A search was made for a uniform that would fit him, but none could be found, the only thing of that nature large enough for him being a pair of divided skirts, which he put on, cutting them off at the knees. His appearance with this costume on can be imagined and was so ludicrous that it threatened to break up the practice. However, as soon as he got out on the diamond and began to practice they began to open eyes and wonder. Such stops and throws were made as they never saw before and with such ease and grace that all were at once convinced he was a wonder. The management signed him on the spot and at a good salary, a move they never regretted, as his playing was the sensation of league all the season. Besides being one of the greatest ball players in the business, he is said to be one of the best humored, not a single instance of his ever losing his temper in a game being on record.”

Childs appeared in 53 games for Kalamazoo from June 9 to September 1. His statistics for the 1888 Tri-State League included 11 doubles, 3 triples, 19 stolen bases and a .282 batting average. Childs left the Kalamazoo team in early September and came back east in time to play nine games at the end of the season with the Syracuse Stars of the International League. He played for Syracuse from September 8 to September 19. For the Stars, Childs had 11 hits, 1 double, 1 triple and a batting average of .297.

Childs stayed on with the Syracuse ball club for the following year. He played the entire season with the Stars, appearing in 105 games. Childs finished the 1889 International League season with 145 hits, 21 doubles, 12 triples, 53 stolen bases and a .341 batting average.

Childs and the Syracuse team left the International League in 1890 and moved up to the majors by joining the American Association. Childs appeared in 126 games for Syracuse in 1890. He amassed 170 hits, 72 walks, 14 triples and scored 109 runs. He led the American Association that year with 33 doubles and finished the 1890 season with a .345 batting average and 56 stolen bases.

On January 26, 1891, Childs signed with his hometown Baltimore Orioles, who were also members of the American Association. His Oriole contract stipulated that he was to be paid a salary of $2300 by the Orioles for the 1891 season. He was also given a $200 advance on the day he signed. In early February, the American Association withdrew from Baseball’s National Agreement and decided to conduct operations as an independent major league. This meant that all of the American Association teams, including the Orioles, were no longer bound by the by-laws and clauses that were part of the National Agreement.

The American Association’s withdrawal led Childs to conclude that his Oriole contract had been voided. The Orioles did not agree and still considered him under contract. News of Childs’ availability spread, and in early February the Boston team of the American Association sent their manager, Arthur Irwin, to Baltimore in an attempt to sign Childs. Newspaper accounts stated that Irwin was unable to locate Childs in Baltimore. It appears that Childs did not want anything to do with any of the teams in the American Association. Childs, now considering himself a free agent, signed with the Cleveland team of the National League on February 16, 1891. Childs met with Orioles manager and part owner Billy Barnie on March 2. Childs informed Barnie that he would not be playing for the Orioles in the upcoming season. Barnie said, “The only explanation Childs gave him for leaving the team was that he could do better.” Childs also attempted to return the advance money to Barnie, but the Oriole manager refused to take it.

Baltimore team management then filed an injunction in Baltimore City Circuit Court to force Childs to honor his Oriole contract. Judge Phelps of Baltimore City was selected to rule over the case. The trial opened on April 5, 1891. William Shepard Bryant and the Honorable Bernard Carter represented the Baltimore Baseball and Exhibition Company, and Thomas I. Elliot represented Childs. One hundred and thirteen pages of testimony were read on the opening day of the trial. “The courtroom was crowded with professional and amateur ball players and lovers of the game,” wrote the Baltimore Morning Herald after the first day’s session. The trial gained national attention and on April 22, 1891, the judge finally reached his decision. Phelps ruled in favor of Childs and the injunction filed by the Orioles was dissolved. Childs’ Oriole contract had stated that he was due all of the rights accorded to professional baseball players designated by the National Agreement. Because the National Agreement no longer bound the Orioles, the team could not offer Childs the conditions that they had originally agreed upon, thus voiding the contract. This was the main point of Judge Phelps’ summation in explaining his verdict. By the time the case was eventually settled, the Orioles had already filled the second base position. It seems that Oriole management pursued the Childs case on principle rather than necessity.

Baseball fans in Cleveland were overjoyed at the outcome. When the verdict was announced, the Cleveland management telegraphed Oriole manager Billy Barnie with the phrase, “He who laughs last, laughs best.”

Cupid Childs went on to play his next eight major league seasons with the Cleveland Spiders of the National League. The Spiders were led by their hardnosed and hot- tempered player-manager Patsy Tebeau. Baseball historian Lee Allen said, “Patsy Tebeau was the prototype of all hooligans and his players cheerfully followed his example.” At one time, Tebeau’s Cleveland Spiders lineup included Hall of Fame players Cy Young, Jesse Burkett, Buck Ewing, George Davis, John Clarkson and Bobby Wallace. The Spiders also had outstanding players like Chief Zimmer and Ed McKean.

Childs hit .281 batting and stole 39 bases in his first year as a Spider. He scored 120 runs and worked the National League pitchers for 97 walks in 141 games. The following year, Childs had a .317 batting average while playing in 145 games. He also led the National League that season with 136 runs scored and a .443 on-base percentage.

The next year Childs had a .326 batting average and stole 23 bases for the Cleveland team. He finished the season with 120 walks and 145 runs scored while playing in 124 games. Amazingly, Cupid struck out just twelve times for the entire 1893 season.

Childs had another good year in 1894, hitting .353. He had 169 hits, 107 walks, 21 doubles and 12 triples for the year. He also scored 143 runs and stole 17 bases. Throughout his career Childs missed his share of games due to injuries and sickness but he also was capable of playing hurt. On August 8, 1894, Childs fell and broke his collarbone after he was tripped by Pittsburgh first baseman Jake Beckley while he was running down the first base line. Cupid must have had great recuperative powers because he was back in the Cleveland lineup at second base just 13 days later. In September of that year, Childs handled 16 chances without an error in the first game of a double header against Brooklyn. Remarkably, Childs finished the 1894 National League season with just 11 strikeouts.

In the spring of 1895, Childs was having contract problems and briefly left the club on April 23. He and the Cleveland team were at odds over a difference of $300 in his contract. Childs declined to leave on the train with the ball club for a road trip and said that he wanted to join the New York team. Childs and Cleveland management eventually came to terms and Cupid rejoined the team for the rest of the 1895 season.

The contract troubles may have affected Childs because his batting average slipped to .288 that year. However, he was on base enough to score 96 runs and steal 20 bases. He also hit his career high in home runs that season with four and knocked in 90 runs in 120 games.

Childs bounced back in 1896 with a monster year. He had 177 hits, 100 walks, 24 doubles, 106 RBI, and scored 106 runs in 132 games. Childs struck out just 18 times during the season. He finished the 1896 National League season with a .467 on-base percentage a .355 batting average and 25 stolen bases.

The 1897 season was Cupid Childs’ last great year in the major leagues: a .338 batting average, 105 runs, and 25 stolen bases accompanied by 15 doubles, 9 triples, and 1 home run.

Childs played his final year for Cleveland in 1898. He closed out with a .288 batting average and 90 runs scored. Injuries took their toll on Cupid, and he ended up missing 39 games during the season.

The Cleveland Spiders played in three postseason Championship Series while Childs was a member of the team. The first was in 1892 when the National League played a split season. The Boston Beaneaters had the best record for the first half of the season, and Cleveland had the best record for the second. The two teams played each other at the end of the year in a Championship Series that Boston eventually won. Childs played great for Cleveland, finishing the series with a .409 batting average. He had 9 hits including 2 triples and 5 walks in the five Championship games. Childs handled 32 chances at second base during the series without an error.

The other two post-season appearances the Spiders made were in the Temple Cup in back-to-back years. The Temple Cup was a Championship Series that was played at the end of the regular season between the first and second place teams of the National League. It was played from 1894 through 1897. The Cleveland Spiders played the Baltimore Orioles in two hotly contested Series in 1895 and 1896. The Spiders were the second place team during the regular season in each of the two years they participated in the Series. Cleveland won the Temple Cup in 1895 but lost to the Orioles in 1896. Childs did not hit well in either of the Temple Cup Series. Even though the Spiders and Orioles were bitter rivals on the ball field, Childs always remained popular in his hometown. “Cleveland second baseman Paca Childs is a Baltimorean and has many friends in this city,” wrote the Baltimore Sun after an Orioles home stand against the Spiders during the 1894 season.

Childs was the all-time base on balls leader for the Spiders team with 758. His .434 on-base percentage as a Spider was the second highest in team history to Jesse Burkett’s .435. His .318 career batting average as a Spider is second on the team’s all-time list, well behind Burkett’s .355. Childs ranks third on the Spiders all-time hit list with 1239 after Ed McKean (1694) and Burkett (1453). He finished third on the team with 71 triples (McKean had 127, Burkett 92) and third in runs scored with 941 close behind McKean (996) and Burkett (987). Finally, he leads the Spiders with 56 sacrifice hits. Childs, Burkett, and McKean were the Big Three of the Cleveland Spiders.

The Spiders had an overall record of 613 wins and 470 losses while Childs was with them. In 1899, the Robison Brothers, owners of the Cleveland team, bought the struggling St. Louis club and assumed joint ownership of both National League franchises. The Cleveland ownership then transferred Patsy Tebeau, Cy Young, Jesse Burkett, Ed McKean, Bobby Wallace, Harry Blake, Cupid Childs and a few others over to St. Louis in an effort to strengthen the ball club. Unfortunately, Childs contracted malaria while playing for St. Louis that year. When Childs was finally healthy enough to return to the lineup, he was not up to par and finished the 1899 season with a .265 batting average. The year before in 1898, the St. Louis team had won 39 games and finished last in the twelve-team National League. With the addition of the new manager and players from Cleveland, the St. Louis Perfectos won 84 games and finished fifth.

The following season, the Chicago Orphans of the National League purchased Childs’ contract from the St. Louis club. Childs and the Orphans management came to terms, and he became a member of the Chicago team for the 1900 season. Only after second baseman Bill Keister had committed to the St. Louis team, did St. Louis manager Tebeau agree to let Childs go.

When a reporter asked Childs how he felt about joining the Chicago team he replied, “I am pleased with the idea of playing in Chicago. I had a little hard luck last season and my relations with the St. Louis club were not pleasant for the club or myself. This Chicago team looks good to me, and I think is stronger than ever. The Chicago club always troubled us to beat it and it is much stronger in the box. I have been riding horseback and taking light exercise all winter in Philadelphia to keep myself fit, for I do not want to take any chances of another attack of malaria and another bad season.”

On April 11, 1900, Chicago Orphans manager Tom Loftus announced his starting lineup for the upcoming season. Childs had won the starting second baseman position and was batting second in the batting order. “Childs is showing beautiful form at second and his work is a sign of promise,” wrote the Chicago Tribune regarding Cupid’s play in late April of the 1900 season.

Childs was getting older now, but he evidently still possessed the old Cleveland Spiders fighting spirit. In May of 1900, Childs and Pittsburgh player manager and future Hall of Fame member Fred Clarke got in a fistfight at the train station in Pittsburgh. Childs and Clarke had collided with each other at second base in a recent game. Clarke had dared Childs to fight him on the field that day, but the two were separated before the trouble could escalate. Childs and Clarke then ran into each other at the train station in Pittsburgh when both teams were leaving the city. The two exchanged words and a fistfight ensued. Sources at the time said that there had been bad blood brewing between the two players that had dated back to previous seasons. Eyewitness accounts said both players took a beating but that Clarke got the worst of it.

At some point early in the 1900 season, Childs began to feel the effects from his previous bout of malaria. His weakened state was causing his hand-eye coordination and reflexes to fail him. Although the press was relatively kind to Childs, there were many instances of thrown balls going right through his hands on potential double play opportunities. Childs evidently knew something was wrong because in early June of 1900 he told the Chicago Tribune, “If I last through this season I will quit baseball. I have an excellent business opportunity and will get out of the business.” Further along in the article the Tribune observed, “Childs is playing good ball for Chicago and helping the team by his clever bunting. He is drawing more base on balls than any man on the team and fielding well.” Nevertheless, Childs finished the season with an uncharacteristically low batting average of .241.

The business deal must have fallen through because Childs returned to the Chicago team for the 1901 season. He never got on track and hit just .258 in 63 games. He was released from the Chicago team on July 8, 1901. Dating back to the nineteenth century, major league players who were past their prime would often catch on with minor league teams to finish out their professional careers. Childs took this route and signed on with Toledo of the Western Association. He appeared in 71 games for Toledo in 1901. He had 17 doubles with 14 stolen bases and ended the season with a .247 batting average.

Childs must have regained some of his strength because he bounced back to have a good year in the minors in 1902. Cupid started out the season with the Jersey City Skeeters of the Eastern League. He played in 33 games for the Jersey City team and hit a solid .290 with 5 doubles, 2 triples, and 6 stolen bases. Childs then moved on to the Syracuse team of the New York State League, where he had 102 hits, 12 doubles, 6 triples, 14 stolen bases and a .358 average in 74 games.

In 1903, Childs signed on with manager Wilbert Robinson and his hometown Baltimore Orioles. The Birds were starting their inaugural season in the Eastern League. Childs came to spring training in good shape and played well. On April 28, the Orioles played an exhibition game against the University of Maryland baseball team at Oriole Park. The Orioles won the game by the score of 26-0. Cupid was three for five with two triples and three runs scored. He played flawlessly at second base that day with one putout and three assists. “Childs made a sensational catch of a fly ball in the first inning,” wrote the Baltimore Sun in their comments on the game.

Childs was with the Orioles in spring training and through the first six games of the regular season. Unfortunately for Childs, his services had been reserved for the 1903 season by another team. The Montgomery, Alabama, team of the Southern Association had engaged Childs prior to his signing with Baltimore. The Orioles tried to acquire Childs’ contract back from the Montgomery team, but that club’s management refused to deal. It was reported that the Orioles offered a sum of four figures to the Montgomery club for Childs’ release. On May 4, Childs sent a telegram to Montgomery manager Lew Whistler stating that he would not play for the Montgomery team under any circumstances. Unfortunately for Childs, the final decision was made for him. On May 6, Eastern League President P.T. Powers wired the Orioles saying that Childs would no longer be allowed to play in the Eastern League and that he must report to the Montgomery ball club. Childs was so distraught over the matter that he threatened to play for the Johnstown team of the New York State League. Childs soon came to realize that he had no other alternatives available to him so he reluctantly boarded a southbound train for Montgomery and reported to the team.

Childs played the entire 1903 season with the Montgomery Legislators. He appeared in 108 games and had 104 hits, 7 doubles, 1 triple and he finished the year with a .318 batting average. The Atlanta Constitution on June 17 reprinted a brief article about Childs from the Shreveport Times that described Childs’ work in glowing terms: “‘Cupid’ Childs is about one half of the Montgomery team. The way the old leaguer covers the ground and swats the ball reminds one of ‘Cupid’s’ palmy days when he was the ‘whole thing’ with the Clevelanders.”

In February of 1904, Childs was listed on the Montgomery team’s reserve list at second base, but he does not appear in any of the Southern Association statistics for the season.

Childs did play in the New York State League in 1904, appearing in 41 games for the Schenectady team (which moved to Scranton mid-year). Cupid was now at the end of the line and finished the 1904 season with just a .245 batting average. Childs may have made some attempts to continue his baseball career in 1905. In August of that year, a brief line in a local newspaper reported that Childs had made an attempt to catch on in the New York State League. Childs does not show up in league records that season and more than likely did not play any organized baseball after the 1905 season.

With his baseball career over, Cupid Childs began working as a coal driver in Baltimore City. As did many people of his generation, Clarence “Cupid” Childs died at a young age. He passed away after a lengthy illness at age 45 on November 8, 1912, at Saint Agnes Hospital in Baltimore. The cause of death was listed as Bright’s disease. His wife Mary and his eight-year-old daughter Ruth survived him. Childs had just recently bought a coal business and home that were both located at 1800 West Pratt Street in Baltimore. Unfortunately for Childs, his debilitating illness had rendered him bedridden. Because of this he was no longer able to oversee the daily operations of his coal company. A few weeks before his death, a local paper had reported that the bank was ready to foreclose on his new house and business. When Childs passed away, his obituary stated that his funeral service would take place at his residence at 1800 West Pratt Street. Since that was the address of his new home, it appears that the bankers may have worked out a last-minute deal to allow the Childs family to keep their home. Clarence L. “Cupid” Childs is buried in Loudon Park Cemetery in the southwestern section of Baltimore City.

A portion of Cupid Childs’ obituary from the Baltimore Sun of November 9, 1912, read:

“Childs was considered the fastest second baseman and one of the heaviest hitters in the major leagues. He was the idol of baseball fans and although never playing on the old Oriole team in Baltimore, he was always given a warm welcome because he was a Baltimore boy.”

Cupid Childs played a total of 13 seasons in the major leagues. He appeared in 1457 major league games and finished with 1721 hits. He ended his major league career with 991 walks, 1214 runs scored, 205 doubles, 101 triples and 269 stolen bases. His .416 career lifetime on-base percentage is right below Stan Musial’s .417.

Cupid averaged 6.3 chances a game at second base during his thirteen-year major league career. That places him fifth on the all-time list for chances per game by a second baseman. Childs finished his major league career with a .930 fielding percentage. However, taking into consideration his outstanding offensive production and given a little luck, Childs might already be in Cooperstown. He compares favorably with many of the second baseman in the Hall of Fame. Maybe it is time to take another look at him.

Acknowledgments

I am especially grateful to Ray Nemec and Reed Howard, whose kindness and help made this article possible. Ray provided me with Childs’ minor league statistics. Reed sent me the dates and places where Childs played in the 19th century.

I would like to thank Cupid Childs’ cousin, LSP, for the use of the two pictures in this biography.

Sources

Allentown Chronicle and News, various issues

Baltimore City Directories

Baltimore Morning Herald, various issues

Baltimore Sun, various issues

Baseball Almanac (www.baseball-almanac.com)

Hoie, Bob, Carlos Bauer, et al., eds. The Historical Register: The Complete Major &

Minor League Record of Baseball’s Greatest Players. San Diego and San Marino:

Baseball Press Books, 1998.

Philadelphia Inquirer, various issues

Phillips, John. The 1894 Cleveland Spiders. Cabin John, Maryland: Capital Publishing Company, 1991.

ProQuest Newspapers:

Atlanta Constitution, various issues

Chicago Tribune, various issues

Thorn, John, Phil Birnbaum, Bill Deane, et al. , eds. Total Baseball: The Ultimate Baseball Encyclopedia. 8th ed. Toronto: Sport Media Publishing, Inc., 2004.

United States Census, 1860.

Wright, Marshall D. The International League: Year-by-Year Statistics, 1884-1953. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998.

Full Name

Clarence Lemuel Childs

Born

August 8, 1867 at Calvert County, MD (USA)

Died

November 8, 1912 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.