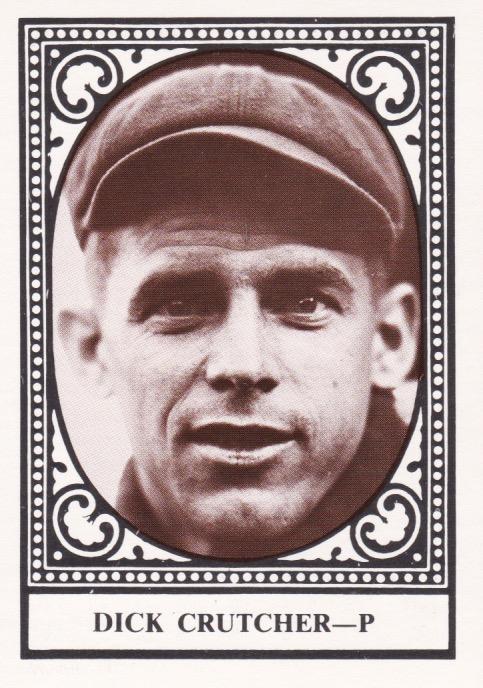

Dick Crutcher

On a cold September day in 1914, Richard Luther Crutcher Jr. pitched the most significant game of his brief major-league career. The stands of the ancient South End Grounds were sparsely populated with a thousand hardy souls for whom the warmth of the pennant race outweighed the discomfort of the November-like weather.1 The Boston Nationals had been expected to contend that year2 but had started slowly before plummeting into the cellar and remaining there into July. Then they had caught fire and vaulted past the pack to take a 2½- game lead with three weeks to go.

On a cold September day in 1914, Richard Luther Crutcher Jr. pitched the most significant game of his brief major-league career. The stands of the ancient South End Grounds were sparsely populated with a thousand hardy souls for whom the warmth of the pennant race outweighed the discomfort of the November-like weather.1 The Boston Nationals had been expected to contend that year2 but had started slowly before plummeting into the cellar and remaining there into July. Then they had caught fire and vaulted past the pack to take a 2½- game lead with three weeks to go.

Crutcher had been drafted from the St. Joseph team of the Western League the previous fall and there had been high hopes for the man the Boston Globe had referred to as the “Strikeout King.”3 His nickname, Little Dick, stemmed from both his heritage as Richard Luther Crutcher Jr. and from the 148 pounds he carried on a 5-foot-9-inch frame.4 Even Deadball Era managers and scouts preferred large, strapping men who could throw hard, and Dick’s slight build was repeatedly noted by commentators.

Crutcher was born in Frankfort, Kentucky, on November 25, 1889, to Richard and Emma Crutcher. The Crutchers were farmers who had moved to the city of Frankfort, where the elder Crutcher was involved in politics and the couple ran a boarding house.5 Their first-born son, Lewis, would play ball in 1907 with Kansas City in the American Association and then for three more years with Frankfort in the Blue Grass League before retiring after the 1910 season to become a bookkeeper with a local firm.6

Like his older brother, Dick Crutcher also began his professional career pitching in the Blue Grass League.7 In 1908 he pitched briefly for Lexington8 before spending the next two years with the Frankfort nine. Sometime during that summer, Crutcher experienced the first bout of the arm trouble that would surface occasionally throughout his career.9 The problem passed and he was well enough to pitch during August and September.10

Crutcher’s debut season was impressive enough that the local papers referred to the “kid” pitcher as an essential part of the team’s plans for 1909.11 However, after beginning the season with Frankfort, he moved west to Oklahoma and signed first with Muskogee12 and then with the Sapulpa club of the Western Association in July.13 During his brief time with the Oilers he pitched a one-hitter against Springfield on August 4.14 Later that year he signed with Enid15 and spent parts of the next two seasons there, winning 20 games in 1910.

Crutcher then joined the St. Joseph Drummers of the Western League, with whom he spent the next three-plus years. Although 3-7 during the remainder of 1910, he rebounded to 9-4 in 1911 despite missing time because of illness. In 1912 he established himself as a regular by winning 18 of 31 decisions and pitching more than 300 innings for the second-place team. His success continued in 1913, when he won 19 games and lost 17 for the third-place Drummers. Crutcher struck out 211 batters in 304 innings but also walked 145, by far the most in the league.

The Braves trained in Macon in the spring of 1914 and there was optimism in camp regarding several new young hurlers. Crutcher was well regarded and rated a mention by Hugh Fullerton. The nationally-known sportswriter said of Crutcher, “His right arm ought to figure strongly in the race.” Despite a setback with problems in said right arm, Little Dick was slated for regular use when the championship season began.

Unfortunately for Braves fans, the team started poorly and quickly fell off the pace. Opening Day in Brooklyn was a farce as the home team hit Lefty Tyler early and often en route to an 8-2 win. The only bright spot was the performance of Crutcher, who pitched three innings of hitless relief and also doubled and drove in a run in his only at-bat.

On April 22 manager George Stallings gave Crutcher the opportunity to start against the Phillies and he was a success both on the mound and at the plate. The rookie had a pair of hits and pitched a complete game, striking out four while walking only one batter. However, he also gave up ten hits and was consistently in trouble before the Braves broke through in the ninth to get the tiebreaking run, the tally being scored by Crutcher himself. It was an auspicious beginning but it was not a harbinger of things to come.

The rookie pitched well in his next start but lost a 4-0 decision to the Brooklyn Robins. A bloop double followed by an error led to three runs in the decisive sixth inning. The defending champion Giants and Rube Marquard were next and if any team was to be Little Dick’s bête noire, it would be McGraw’s men, who tormented him numerous times over his career. On this day the first four batters hit safely and Crutcher was gone by the third inning of the 11-2 defeat.

Stallings matched the rookie against Marquard again on May 7 and the results were only slightly better. As was becoming common, Crutcher was in constant danger but managed to take a two-run lead into the late innings. Three hard hits beginning the bottom of the eighth cut the margin to 5-4 and sent Crutcher to the showers. Dick Rudolph relieved and was victimized by some bad breaks in the eventual 7-6 Giants win.

In his next start Crutcher lasted only five innings before being lifted for a pinch-hitter in a 4-2 loss to the Reds. Four days later, on May 19, he held the Pirates scoreless through three innings before the roof fell in and five runs scored, leading to 7-5 Pittsburgh victory. The rookie’s wildness was evident in a hit batter and then a pair of walks that opened the floodgates. Those four innings marked the end of Crutcher’s stint as a regular Braves starter.

For the rest of the season, Stallings primarily used the rookie in relief with a few spot starts because of doubleheaders or the need to rest other pitchers. Most of the relief outings occurred in low-leverage situations with Boston trailing. If saves were recorded in those days, Crutcher would have had none, and he completed only five of his 15 starts.

Little Dick was matched against Grover Cleveland Alexander in the second game of the Decoration Day twin bill but was pulled in the sixth because of control problems and did not figure in a 3-2 ten-inning Boston win. In his next start, a month later on June 30, he lasted six innings. Wildness was an issue again and he allowed seven hits and four walks in a game that ended in a 5-4 13-inning defeat. But on July 6 Crutcher turned in his best effort, pitching his only major-league shutout, against the Robins. Crutcher allowed six hits and one walk in the 1-0 decision that left the Braves still 14 games out of first place.

On July 19 Crutcher carried another shutout into the seventh inning against the Reds but was pulled after allowing a pair of runs that broke the scoreless tie. The Braves rallied to score three times in the ninth to win and began to build some momentum. They next steamed into the Smoky City and shut out the Pirates in four of five games. The one exception was when Crutcher again weakened and gave up a 4-2 eighth-inning lead. He left with the bases loaded in a tie game and the next batter unloaded them with a double off George Davis, leading to an 8-4 defeat.

In spite of the loss, the Braves continued on a hot streak that saw their record rise to ten games above .500 after a doubleheader sweep of the Reds on August 17. During the streak Stallings had been working his top starters hard and he decided to throw Crutcher into the breach on the 18th. The result was positive – six innings pitched with only a pair of hits allowed – but although the three Cincinnati runs were unearned, the decisive rally was triggered by a pair of walks. The 3-1 defeat did not stop the Braves’ surge but it was three more weeks before Stallings gave Crutcher another start.

That start came the aforementioned unseasonably cold day in September in Boston with the Braves holding a 2½-game lead over the suddenly struggling Giants. A brutal skein of three doubleheaders in four days left the Braves staff worn thin and gave Crutcher the chance. The Braves got to Eppa Rixey for three early runs. Philadelphia plated a run on a double-play grounder in the fourth and then broke free in the fifth, scoring three runs off Crutcher and relief pitcher Paul Strand to take a one-run lead. Boston ended up winning the game, scoring two runs in the last of the ninth, and maintained its lead over the Giants. Crutcher’s performance had been disappointing and although he had walked only one batter it had led to a big inning and he had given up eight hits as well. It was Crutcher’s last meaningful impact on the pennant race; he sat on the bench as the Braves pulled away from their rivals. Stallings gave him two more starts after things were all but decided. His final appearance was a 15-2 romp over Brooklyn on the next-to-last day of the regular season. Although active for the World Series, Crutcher never made it into a game as the Braves swept the highly favored Athletics.

Crutcher’s final 1914 statistics were not pretty: a 5-7 record with an ERA of 3.46 and 48 strikeouts and 66 walks in 158 innings pitched. The sole highlight was a fielding percentage of .981, which placed him fifth in the league among pitchers. Yet even after a subpar first year, Stallings saw enough promise in the youngster to re-sign him for 1915. Crutcher appeared very much in the defending champions’ plans throughout the spring and started the third game of the season, a solid 5-1 win over the Robins. However, Stallings had brought the hook again in the eighth inning, showing the same lack of patience or confidence as in the prior season. The Robins then hit Dick hard four days later and drove him into the bullpen.

It was more than a month before Crutcher drew another start, and he went the distance in a sloppy 5-5 tie against the Giants that was called on account of darkness. On June 20 the Cardinals drove him from the box by the fifth inning of an 8-2 loss. His last major-league appearance came on the 26th, when he relieved Tom Hughes and poured gasoline on the fire by giving up three hits and a hit batter without recording an out. The next day Crutcher, with a 2-2 record and a 4.43 earned-run average for 1915, was released along with catcher Walt Tragesser to Jersey City in the International League. Dick Crutcher’s major-league career was over at the age of 25 and his 1915 Braves totals were particularly grim: 2-2 with a 4.43 ERA. He gradually slid out of the limelight, his name surfacing only briefly in a series of strange incidents. One of these occurred when indifferent outfield play by the great Olympian Jim Thorpe angered Crutcher enough for the smaller man to threaten to “take a little slap” at his Jersey City teammate. Given the size and physiques of the combatants, it was fortunate the confrontation did not lead to blows.16 Crutcher ended up 9-9 for a mediocre Skeeters team.

Later that year the Braves’ share of the gate receipts for a September game in St. Louis was attached by deputy sheriffs as a result of a disagreement with Kansas City’s American Association club. The Blues alleged that they had not received agreed-upon compensation from Boston for a player sale, nor had they received Crutcher and Lawrence Gilbert as agreed.17 There must have been some merit to the Kansas City case; Crutcher played there for the next three seasons.

Dick was a mainstay of the Blues rotation in 1916, compiling a 16-15 record for a fourth-place club. The following year arm troubles struck again and Crutcher was winless in three decisions, leading to friction with management. A syndicated feature ran in many papers insinuating that he was a lazy malingerer who could be great if he wanted to but instead had been suspended for “failing to condition himself.”18 A contemporary article in the Kansas City Star stated that Crutcher was consulting a local dentist who believed the arm trouble was caused by abscesses at the roots of his teeth.19

Crutcher’s 1918 record was similarly truncated and he spent time with both the Blues and with Joplin of the Western Association before traveling north to Wisconsin.20 He did war work at the Nash Motor plant in Kenosha and pitched for the company team.21 He also appeared with the Manitowoc Shipbuilders and was the winning pitcher in the game that decided the Lake Shore League championship.22 After the war he had an unsuccessful stint with Joplin before returning to Wisconsin.

Crutcher pitched for Manitowoc, Oshkosh, and Waukesha along Wisconsin’s Lake Shore and, other than an abortive attempt to rehabilitate his arm at French Lick, Indiana,23 and rejoin Organized Baseball in 1922, he remained in the area for the rest of the decade.24 He continued to be employed by Nash, pitching for and managing the Nash Motormen semipro team before returning to Kentucky.25 Back in Frankfort, he found work as a duplicating equipment operator for the state Highway Department.26 He had married Ethel Armstrong of Frankfort before the World War. The couple had no children and were divorced by the early 1950s.27 On June 18, 1952, Crutcher complained of indigestion and went to bed. He died of a heart attack the next day and was buried in Frankfort Cemetery.28

Or maybe not. A few years later, baseball writer Shirley Povich encountered someone claiming to be Dick Crutcher. The reporter used the Encyclopedia of Baseball to test the man and while the stranger got the baseball statistics right, he claimed a date of birth of 1893 instead of the listed 1891 (which was off by two years). While Povich was willing to overlook that discrepancy, he could not help but notice that Crutcher was listed as having died several years before. When confronted with the fact, the visitor became angry and stormed out of the office.29

Who was it? The 1900 census showed Crutcher with six siblings but neither of his brothers was born in 1893 or 1891. In fact Dick was the youngest boy by several years, having older brothers Lewis (born 1881 or 1882) and Edward (born 1885).30 Both were still alive at the time and could be possible suspects but to what purpose or motive?31 Because Little Dick had been a member of the Miracle Braves, a team with a legend that still resonated a half-century later? Regardless of the impostor’s identity, the story was a final, bizarre coda to Crutcher’s life.

Sources

All statistics are taken from www.baseball-reference.com unless otherwise noted. All references to standings for the 1914 season are taken from www.retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 J.C. O’Leary, “Never Quit Braves Win Out in Ninth,” Boston Daily Globe, September 12, 1914.

2 J.C. O’Leary, “Braves Fourth or Better,” Boston Daily Globe, April 12, 1914.

3 “Braves Get Two New Players,” Boston Daily Globe, December 31, 1913.

4 ”Question Box,”Oakland Tribune, March 28, 1915.

5 Both the Franklin County Marriage Register for 1878 and the 1880 US Census, First Magisterial District of Franklin County, show Richard Crutcher, Sr.’s occupation as farmer; “Election Officers,” Frankfort Weekly News and Roundabout, September 24, 1898, and “Entries in Democratic Primaries,” Frankfort Weekly News and Roundabout, November 5, 1904, show Richard serving as an election judge and as a nominee for the office of Jailer: 1920 US Census, Bridge Precinct, Magisterial District No. 3, of Frankfort shows Richard as the head of household and Emma as “Manager,” “Boarding House.”

6 Lexington Herald, January 23, 1907; “Pitcher Crutcher is Now Bookkeeper,” Lexington Herald, November 22, 1910. It appears that Baseball-Reference has attributed Richard’s stint in Kansas City to Dick and his three years with Frankfort to Edward Crutcher. However, the above sources refer to Lewis (or Louis) as the Crutcher in question in both instances. See also “Among the Sports,” Oklahoma New-State Tribune, July 29, 1909, which refers to Dick having a brother who played for Kansas City.

7 Commonwealth of Kentucky Death Certificate.

8 “Lexington Will Play Guetigs in Afternoon,” Lexington Herald, April 19, 1908.

9 The Fan, “Diamond Dust,” Frankfort Weekly News and Roundabout, August 22, 1908.

10 “Thoroughbreds Win in Romping Style,” Lexington Herald, September 7, 1908.

11 “Railway Company to Help Frankfort Team, Lexington Herald, March 14, 1909.

12 “Among the Sports,” Oklahoma New-State Tribune, September 2, 1909.

13 “Pioneer Park Bingles,” Muskogee Times-Democrat, July 23, 1909.

14 “News Notes,” Sporting Life, August 21, 1909, 23.

15 “Among the Sports,” Oklahoma New-State Tribune, September 2, 1909.

16 Chandler D. Richter, “Interesting Sidelights on Baseball,” Sporting Life, November 27, 1915, 10.

17 “Forcing Braves to Come Across,” Canton (Ohio) Evening Repository, September 18, 1915.

18 “He Might Star If He’d Buckle Down,” San Diego Evening Tribune, July 24, 1917.

19 “Sore Arm? The Causes,” Kansas City Star, July 22, 1917.

20 “The Blues’ Weird Game,” Kansas City Star, July 20, 1918.

21 “Ball Players on Government Work,” Rockford (Illinois) Register Gazette, August 13, 1918.

22 “Herzog Wins Flag In Shore League,” Racine (Wisconsin) Journal News, September 30, 1918.

23 “Dick Crutcher Starts Work at French Lick,” Manitowoc Herald News, April 12, 1922.

24 “Crutcher, Who Hurled for Manitowoc in Old Days, Is Dead at 62,” Manitowoc (Wisconsin) Herald Times, June 20, 1952; “Slump of Sunday Puts Oshkosh Back to Second Place in Valley League,” Daily Northwestern, Oshkosh, Wisconsin, August 15, 1922; Anonymous, “Crutcher Signs,” Sheboygan Press, September 3, 1920.

25 “Crutcher Leaves Post With Nash,” Milwaukee Journal, December 24, 1929.

26 Commonwealth of Kentucky Certificate of Death; AP Obituary, “Crutcher of Famous 1914 Boston Braves Dies at 62,” Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Gazette and Bulletin, June 20, 1952.

27 Crutcher’s World War I draft registration card from May 28, 1917, states that he was married with no children. The 1920 US Census shows him as married to Ethel Armstrong with no listed children. The Commonwealth of Kentucky Death Certificate shows Crutcher as divorced. None of the obituaries I found mentioned a surviving spouse or children.

28 AP Obituary, Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin, June 20, 1952; http://www.finadagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=53161521.

29 Ralph Berger, “Shirley Povich,” SABR BioProject.

30 1900 US Census.

31 The Social Security Death Index on www.ancestry.com shows a date of death of 1977 for Lewis and 1963 for Edward.

Full Name

Richard Luther Crutcher

Born

November 25, 1889 at Frankfort, KY (USA)

Died

June 19, 1952 at Frankfort, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.