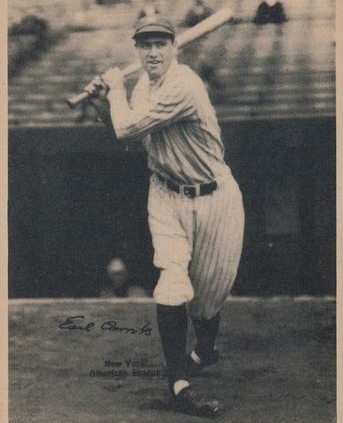

Earle Combs

Modesty and mental and physical toughness embodied the spirit of Earle Combs. His ego never outgrew those values during his baseball career and the remainder of his life. The ultimate team player, he was kind, a gentle man whose life was guided by the Bible. In those still rough and tumble times of baseball he stood out as an anomaly and as a beacon of light in a sport that was still under the pall of the 1919 Black Sox scandal. That he was a baseball player and a good one was only the surface of a man who lived his life as purely as he knew how.

Modesty and mental and physical toughness embodied the spirit of Earle Combs. His ego never outgrew those values during his baseball career and the remainder of his life. The ultimate team player, he was kind, a gentle man whose life was guided by the Bible. In those still rough and tumble times of baseball he stood out as an anomaly and as a beacon of light in a sport that was still under the pall of the 1919 Black Sox scandal. That he was a baseball player and a good one was only the surface of a man who lived his life as purely as he knew how.

Combs was the man in center field between Bob Meusel in left and Babe Ruth in right, a respected ballplayer though eclipsed by his flamboyant teammates. Fred Lieb wrote of Combs, “If a vote were taken of the sportswriters as to who their favorite ballplayer on the Yankees would be, Combs would have been their choice.” Quiet, modest, and intelligent, Combs said upon his induction into the Hall of Fame in 1970, he said, “I thought the Hall of Fame was for superstars, not just average players like me.”

Earle Bryan Combs was born in Pebworth, Kentucky, on May 14, 1899. Of Scottish-German ancestry, he was one of six children of hill farmer James J. Combs and Nannie (Brandenburg) Combs of Owsley County, Kentucky.

This modest man started out to become a schoolteacher after having graduated from Eastern Kentucky State Normal School (now Eastern Kentucky University), where he played basketball, ran track, and played baseball, batting .591 in his final year. Combs began his teaching career in one-room schools in Kentucky. However, he soon found out that he could make more money as a professional baseball player. Batting .444 for the Harlan, Kentucky, team, he was signed by the Louisville Colonels. His first game as a professional player was inauspicious. He made several errors in the outfield, the last giving the opposition the two runs they needed for the win. About his error that lost the game Combs said, “As I went after the dropped ball I was tempted to keep right on going, climb the fence and not stop running until I got to Pebworth.”

Combs sat at his locker after the game downcast and wondering what his life would be as a schoolteacher. He had married Ruth McCollum in 1921 and was concerned about being a breadwinner. His doubts about his baseball career were quickly put aside. Joe McCarthy, the manager of the Colonels, knew he had a good, smart player in Combs and told him, “Look, if I didn’t think you belong in centerfield on this club, I wouldn’t put you there. And I’m going to keep you there.” Combs responded by running down fly balls with his great speed and hitting .344.

In 1923 Combs batted .380 for the Louisville Colonels, and in 1924 the Yankees bought him for $50,000 and two players. He did not immediately report to the Yankees spring training camp because he had been promised a percentage of his purchase price that the Colonels had not paid. For all his modesty and gentlemanly demeanor, Combs was not above fighting for what he believed was his due, saying, “I am not a dumb animal to be browbeaten, cowed, lashed, coerced or goaded into anything I do not think is right.” The Colonels paid.

When Combs did report to the Yankees, Miller Huggins sat him down and had a long talk with him. At Louisville he had been called “The Mail Carrier” because of his base stealing and speed. Huggins, however, told Combs not to worry about stealing bases but as a leadoff man to wait out the pitcher, get on base any way he could, and let the big guns in the lineup, like Ruth, drive him in. Huggins ended the talk with “Up here we will call you the Waiter.” Combs, sensing that Huggins knew what he was talking about, put aside his ego, carried out his skipper’s orders, and served the team well in his new situation. Because of the Yankees’ great sluggers, Combs never stole more than sixteen bases in a season.

Combs was considered in his time the best leadoff man in the American League. Even with his patience in getting walks and sacrifices he collected at least 190 hits five times and wound up his career with a batting average of .325. A left-handed hitter, he could get an extra couple of steps toward first base, enabling him to beat out infield hits. He was not a pull hitter and used the entire field to spray line shots for hits to all fields. Once he lined a pitch in the gap, it often resulted in a three-base hit. He led the league in triples three times and finished his career with 154 triples, averaging more than one three-bagger for every ten games.

Indeed, triples were Earle Combs’ specialty. He hit at least 10 in every season in which he played at least 122 games. Three times (1927, 1928, and 1930) he ran out 20 or more, leading the league each time. His 23 three-baggers in 1927 are the most in an American League season since 1917, equaled only by Cleveland’s Dale Mitchell in 1949. The Deadball Era trio who had better single-season totals is impressive – Sam Crawford, Joe Jackson, and Ty Cobb.

He got off to great start, hitting .400 in the first twenty-four games. Then misfortune struck when he fractured his ankle and was out the rest of the 1924 season. His injury contributed to the Yankees’ missing out on the pennant when they finished 2 games behind the first-place Washington Senators.

Combs returned for the 1925 season, his ankle fully recovered. He slammed out 203 hits, scored 117 runs, and batted .342. But the Yankees did not win the flag. Ruth was out much of the season, and several other players had sub-par years. The Yankees finished in seventh place.

The 1926 Yanks-with Ruth back in shape, Lou Gehrig coming into his own, and Tony Lazzeri at second base-won the pennant and faced the St.Louis Cardinals in the World Series. They lost to the Cardinals when in a memorable moment Pete Alexander struck out Lazzeri with the bases loaded, just after Lazzeri had lined Alexander’s previous pitch barely foul into the left field seats.

Then came the magnificent year of 1927. Lindbergh flew the Atlantic solo, Dempsey and Tunney had their controversial long count fight in Chicago, and the Yanks with arguably the greatest team ever sailed easily to the pennant. Ruth hit his then astounding 60 homers, and Earle Combs set a club record with 231 hits not to be broken until Don Mattingly eclipsed it in 1986 with 238 hits. Showing his great patience at the plate, Combs set the table time and time again for Ruth and Gehrig and their cohorts.

Defensively the only knock on Combs was his weak arm. As the years went by, he strengthened his throwing arm through exercises, but it was never the rifle he would have wanted. Accordingly, Bill James in The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract ranks Combs only 34th in his pick of center fielders.

Although overshadowed by Ruth and Gehrig, Combs was a fan favorite. His quiet demeanor and dogged determination to do his best without much ado endeared him to the fans, so much so that the fans in the right field section of Yankee Stadium took up a collection and bought him a gold watch. Those knowledgeable fans understood his ability to get on base and set the table for the upcoming sluggers as well as his ability to chase down flyballs with his great speed. Combs was always considered the gentleman of the Yankees, earning him the name of the “Kentucky Colonel” for his good manners and quiet dignity. Combs neither smoked nor swore and read the Bible diligently, not caring who knew about it.

Miller Huggins loved the unassuming Combs and Gehrig. Huggins’ sudden death in 1929 devastated the team. Combs profoundly felt the loss of Huggins. The Yanks finished third under Bob Shawkey in 1930. In 1931 Joe McCarthy, Combs’ manager at Louisville, became the Yankees’ skipper. The following year the Yanks won the American League pennant and defeated the Chicago Cubs in the World Series. That was the series in which Ruth was said to have called his home run shot by pointing toward the center field bleachers in Wrigley Field. Was it Ruth’s intent to let the Cubs bench and pitcher Charlie Root know where he was going to deposit the next pitch? Combs recalls the event that day. “I can’t say whether the Babe was actually pointing to the bleachers. He may have been pointing to the pitcher. What I do remember is that the Cubs who had been on Ruth the entire series were on the top step of their dugout really letting Ruth have it. When he smashed that line drive into the stands the Cubs players in the dugout all fell backward as if they had been machine-gunned.”

In 1934 Combs crashed into a wall chasing a fly ball, fracturing his skull and incurring shoulder and knee injuries. He spent two months in the hospital, much of it on the critical list, as doctors feared for his life as well as his career. But Combs with his characteristic mental and physical toughness from his hospital bed said, “You see I’m made of tough stuff” and vowed to return to the Yankees. He returned in 1935 and played in 89 games and also coached. But misfortune struck again, and Combs was out the rest of the season with a broken collarbone. That final injury caused Combs to retire as an active player at the age of 36.

Combs became a full-time coach with the Yankees in 1936. Among his first assignments, he was asked to teach a young ballplayer the special circumstances of playing center field in spacious Yankee Stadium. That young player just up from the San Francisco Seals was Joe DiMaggio. Coincidentally, DiMaggio broke Combs’ and Roger Peckinpaugh‘s jointly held Yankee club record of 29 consecutive games with a hit on his way to a Major League record of hitting in 56 consecutive games in 1941. Combs with his unwavering loyalty to his team helped the young DiMaggio adapt to the center field position in Yankee Stadium.

Combs took his teaching abilities with him in coaching stints for the Yankees, St.Louis Browns, Red Sox, and Phillies through the 1954 season. He then retired to his 400-acre farm in Kentucky.

After his retirement Combs participated in various business and civic ventures. He was a member and the chairman on the Board of Regents of Eastern Kentucky University, his alma mater. A generous person, he quietly and anonymously paid the fees of several needy students attending Eastern Kentucky University.

After a long illness Earle Bryan Combs died on July 21, 1976, in Richmond, Kentucky, at the age of 77. He was survived by his wife Ruth; sons Earle Jr., Charles, and Donald; brother Conley; sister Elsie Seale; and 12 grandchildren. He was buried in Richmond Cemetery.

This modest, quiet intelligent man from the hill country in Kentucky started out to be a teacher, only to find he had the ability to be a fine professional baseball player. When he gained the respect of his baseball peers, he did not change as a person. He remained the ultimate team player, avoiding the self-indulgent ego he might have embraced. Ruth, Gehrig and the rest of Murders Row may have delivered the fatal blows, but Earle Combs set up the scenes of the crimes. He was the rare individual willing to stand up for himself when the occasion called for it and intelligent enough to be the team player if it meant the success of the whole.

Sources

Earle Combs File at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum Library in Cooperstown, New York.

Graybar, Lloyd J. “Combs, Earle Bryan ‘The Kentucky Colonel,’ ‘The Gentleman from Kentucky.’” Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball. David L. Porter, ed. Revised and expanded edition. 3 vols. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000.

James, Bill. The New Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: The Free Press, 2001.

Lieb, Fred. Baseball as I have Known It. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1977.

Light, Jonathan Fraser. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 1997.

Nemec, David. Baseball, More than One Hundred Fifty Years. Lincolnwood, Illinois: Sam Wisnia Publications International, 1997.

New York Times. Obituary. July 22, 1976.

Ward, Geoffrey C., and Ken Burns. Baseball: An Illustrated History New York: Knopf, 1994.

Full Name

Earle Bryan Combs

Born

May 14, 1899 at Pebworth, KY (USA)

Died

July 21, 1976 at Richmond, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.