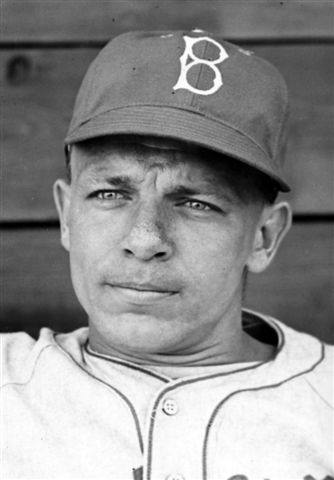

Eddie Stanky

One can statistically evaluate with some degree of accuracy the worth of a baseball player to his team. However, sometimes a player stands out because of characteristics that inspire his teammates and draws the admiration and respect of fans. Eddie “The Brat” Stanky was one of those. Stanky was a gritty, scrappy player, not gifted with natural talent. He worked long and hard to achieve the success he attained. Just 5-feet-8 and 170 pounds, Stanky seemed so much more imposing as he flew into second base with a feet-first, spikes-raised slide to break up a double play.

He was born Edward Raymond Stankiewicz, on September 3, 1915, to Frank and Anna Stankiewicz.1 The family shortened the name to Stanky when Eddie was a boy. In his childhood years in the blue-collar Philadelphia neighborhood of Kensington, Eddie developed the belligerent, enthusiastic, win-at-all-costs attitude that would make him so successful—and reviled—in later life.

Stanky batted just .243 in his senior year at Philadelphia’s Northeast High School, but his drive was exceptional. His single-mindedness and aggressiveness on the field distinguished him from everyone else, even at an early age. “It was baseball that Eddie came to high school for,” said Lester Owen, Stanky’s high school coach. “He said he was going to be a pro baseball player. That was that. No one doubted him. He wasn’t conceited. He was an ordinary boy with extraordinary ambition.”2

That ambition helped get Stanky a contract with his hometown Philadelphia Athletics. In 1935 he was sent to play shortstop for the Greenville (Mississippi) Buckshots of the Class C East Dixie League. After a few weeks, a young, homesick, and discouraged Stanky sent his mother a letter asking for money for train fare home. The response was stern. Eddie was not welcome back at home—quitters weren’t wanted in Anna Stanky’s family. Eddie stayed in Greenville and finished the year with a .301 batting average and 80 runs scored in 104 games.

In 1936 Stanky moved to Portsmouth (Ohio) of the Class C Middle Atlantic League. He raised his batting average 36 points and improved in almost every offensive category. Near the end of the season, he was sent to Williamsport of the Class A New York-Pennsylvania League. He played the last 11 games of 1936 and the first 14 games of 1937 for Williamsport before returning to Portsmouth (now in the Piedmont League). Eddie had played shortstop, second, third, and even pitched during his first two years in the minors, but he was now a full-time second baseman.

With Portsmouth in 1938, he hit .283, drew 127 walks and was hit by a pitch 20 times en route to scoring 110 runs. Early in the 1939 season Stanky was sent to the Macon Peaches of the Class B South Atlantic League. The manager at Macon was Milt Stock, who was also a part owner of the club. Stock, a 14-year major leaguer, saw that Stanky, a right-handed batter, had an excellent eye but no power. He put him in the leadoff position and urged him to be patient at the plate. It worked. Stanky had three excellent seasons at Macon, and made the All-Star team in 1940.

Years later, when Stanky was managing the St. Louis Cardinals, he credited Stock with “planting the seed” that helped him blossom into a successful player and manager. At the time, though, it was hardly a certainty that Stanky would make the majors. It was becoming apparent that despite his small size, he had a disproportionately large temper. Stock taught Eddie to control himself, and told him that being thrown out of games (as happened 15 to 20 times a year) hurt his team’s chances of winning. But Milt wasn’t the only Stock who had a special relationship with Stanky; his daughter, Myrtle “Dickie” Stock, fell in love with her father’s little infielder, and they were married on April 11, 1942.

Shortly after the wedding, Stock dealt his new son-in-law to the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association, where Eddie enjoyed his best—and last—season in the minors. He finished the year with the league’s best batting average (.342) and was named its MVP. Stanky’s manager at Milwaukee was Charlie Grimm. In 1943, the Chicago Cubs made Grimm their manager, and Eddie followed his skipper to Chicago.

Stanky’s inability to back down from a challenge and his habit of crowding the plate led to several beanings during his career. The first, in the minors, was so severe that it left him with a fractured skull and a loss of hearing that kept him out of the armed forces. On April 21, 1943, in the first inning of his major-league debut, Stanky stepped to the plate against Pittsburgh’s Rip Sewell. He was hit in the head by a pitch.

As the Cubs’ second baseman that summer he hit an uninspiring .245. In 1944, Don “Pep” Johnson arrived to take his place, and Stanky found himself warming the bench while Johnson made the All-Star team. Eddie made a simple demand to Grimm: Play me or trade me.3 Grimm acquiesced, and on June 6 dealt Stanky to the Brooklyn Dodgers for lefty pitcher Bob Chipman.

In Brooklyn Stanky replaced the Navy-bound Billy Herman at second base, and in 1945, his first full season with the Dodgers, he started to make a name for himself. His hard-nosed style of play ingratiated him with the fans, who loved his spirited approach to the game. Stanky drew 148 walks in 1945—a National League record at the time; he also led the league in runs scored with 128.

Brooklyn fans adored him. He was given nickname upon nickname: Stinky and Muggsy were popular. However, the most famous nickname, the one that stuck with him, was The Brat, a reference to the snarling, clamorous, hot-headed edge to Stanky that came out in moments of high emotion or tension. The Brat was more of Stanky’s on-field alter-ego. The off-field Eddie Stanky was less of a dervish, very attentive, and spent much time learning about what it might take to be a major-league manager.

Stanky loved being a Dodger and the fans loved him, honoring him with an Eddie Stanky Day on September 8, 1946. His respect for the Dodgers uniform and the team it represented outstripped everything. In May 1946 he was involved in a fistfight with former teammate, Cubs shortstop Lennie Merullo, which was so unruly it nearly “inspired a riot.”4

In 1947 Stanky was elected to his first All-Star squad. He got 141 hits, scored 97 times, and made just 12 errors at second base in helping spark Brooklyn to the pennant. The 1947 season was also the year Jackie Robinson integrated baseball. Peter Golenbock, in his book Bums, contends that Stanky told Robinson when he reported to the Dodgers that he didn’t like him but that they would “play together and get along” because they were teammates.5 More recent research has challenged this. Jonathan Eig, in his book, Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season, says “in accounts written shortly after the 1947 season,” both Rickey and Robinson “rated Eddie Stanky as Robinson’s earliest important backer.”6

“Dad talked about that first game and Jackie a lot,” said Stanky’s son Mike. “He was so impressed by Jackie’s raw ability and the way he dealt with everything he had to handle, that, despite what’s been written over the years, they became really close. I think they both discovered that, despite their obvious differences, they were alike, very much alike.”7

Brooklyn lost the ’47 World Series to the Yankees in seven hard-fought games, during which Stanky hit .240. Days after Stanky signed his 1948 contract, and reported to the Dodgers’ training facility in the Dominican Republic, Rickey traded him, on March 6, to the Boston Braves, for utility man Carvell “Bama” Rowell, first baseman Ray Sanders, and $40,000.

Stanky received the most votes of any second baseman in the National League All-Star voting for 1948, and was hitting well over .300 at the break. But while at Ebbets Field for a July 8 battle against the Dodgers, he collided with Dodgers third baseman Bruce Edwards and emerged with a broken ankle and a torn ligament. He was unable to play in the All-Star Game and did not return to action until September 19, when the Braves were close to sewing up their first pennant in 34 years. Boston, with Sibby Sisti handling most of the second-base duties in Eddie’s absence, made Stanky a pennant winner for the second year in a row. The Dodgers finished in third place.

In the World Series, the Braves lost to Cleveland in six games. Despite Stanky’s leg being “a little below par,” Boston manager Billy Southworth named him to the starting lineup and played him in each contest.8 Playing through the pain, Stanky had a .524 on-base percentage, with seven walks, and four hits. When doctors operated on him two months later, they removed two bone fragments from his ankle joint.

From the start of spring training in 1949, Southworth began to work his players extra hard, and some of them bridled at this treatment. It was to be the beginning of a long year, filled with controversy, for both Eddie and his teammates.

Stanky batted a solid .285 with 90 runs scored. But he started making enemies in the clubhouse, amid rumors that he would take over the managing job from Southworth. One controversy erupted on July 23 in a game against Pittsburgh. The team’s best pitcher, Warren Spahn, was on base in the third inning. Spahn was credited with a stolen base after a hit-and-run called by leadoff man Stanky, who had his manager’s blessing to call plays, went awry. Later in the game, Spahn reached first again, and again, Eddie sent him to second on a hit-and-run. This time, Stanky made contact, grounding the ball to third. Spahn made second on a wild throw and went for third, where he was tagged out. In the ninth inning on this hot day, Spahn blew a three-run lead, and the Braves lost, 12—9.

Reporters immediately assumed that Spahn had run too much on the base paths and had been tired during that last inning on the mound. The blame for “exhausting” Spahn was placed squarely on Stanky for calling the hit-and-runs. Leo Monahan of the Boston American said Stanky’s teammates were grumbling about The Brat’s assumed authority. Another writer said Eddie’s mates were outraged at his “takeover attitude.”9 Stanky was livid. His response dripped with frustration, and his anger was palpable in every word. As The Sporting News reported him saying: “I’m always playing to get another run for my club and prevent the other team from getting runs . . . so far as taking over, I only do what I can to win the games and leave that “takeover attitude” to second-guessing bushers. I resent the implication that I exceeded my authority in putting on plays. I have always co-operated with any manager I played for 100 per cent. I have always played to win. And that’s the way I’ll continue until I quit the game.”10

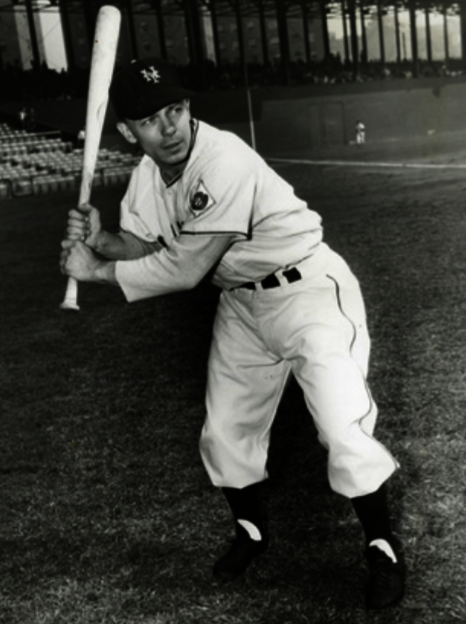

The incident was the low point of the season. Southworth, reportedly on the verge of a breakdown, left the team on August 16 with the Braves in fourth place at 55-54. Coach Johnny Cooney replaced him as manager, but when Southworth announced that he would be coming back in 1950, Stanky was all but gone from the team. On December 14, 1949 the ax fell, and Stanky and his double-play partner, Al Dark, were traded to the New York Giants—managed now by Leo Durocher—for outfielders Sid Gordon and Willard Marshall, infielder Buddy Kerr, and right-handed pitcher Sam Webb.

The rift between Stanky and Durocher that followed Eddie’s trade from Brooklyn was quickly repaired. Durocher let Stanky play the way he wanted, and Stanky thrived. In 152 games during the 1950 season he hit .300, with a league-high .460 on-base percentage, 115 runs scored, and he also led the league in walks (144) and times being hit by a pitch (12). He was named to the National League All-Star squad, was selected as Player of the Year by the New York baseball writers, and finished third in the league MVP voting.

More importantly, with free rein and total agreement from his manager, the Stanky style of play flourished. The Giants improved from a 73-81, fifth-place finish in 1949 to an 86-68 mark and third place during Stanky’s first season with the club.

In an August 12 game second baseman Stanky started to wave his arms, mimicking the pitcher’s windup, while a Phillies hitter stood in the batter’s box. After a warning from umpires that Stanky did not heed, he was ejected from the game. Philadelphia catcher Andy Seminick, the victim of Stanky’s antics, was not satisfied with the punishment and took out Stanky’s replacement, Bill Rigney, in a violent collision at second base. Police were required to quell the ensuing bench clearing brawl. Durocher protested the contest and said, “What’s wrong with trying to fool the batter, anyway? Everyone tries to do that one way or another.” Commissioner Ford Frick wasn’t buying the excuse, and ordered umpires to eject any player who engaged in similar tactics.11

Things got even more exciting in 1951, when Stanky hit a career-high 14 home runs and scored 88 runs. However, his batting average and on-base percentage each dropped almost 60 points. The Giants, in what became known as the “Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff,” made a late-season sprint to force a three-game playoff with the Brooklyn Dodgers. While Bobby Thomson jogged around the bases after his season-ending home run, Stanky jumped on the back of his manager, standing in the third-base coaching box, and the two danced jubilantly together down the baseline.

Things got even more exciting in 1951, when Stanky hit a career-high 14 home runs and scored 88 runs. However, his batting average and on-base percentage each dropped almost 60 points. The Giants, in what became known as the “Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff,” made a late-season sprint to force a three-game playoff with the Brooklyn Dodgers. While Bobby Thomson jogged around the bases after his season-ending home run, Stanky jumped on the back of his manager, standing in the third-base coaching box, and the two danced jubilantly together down the baseline.

The Giants lost the World Series to the Yankees in six games, Stanky hitting a lackluster .136, but more memorable than his anemic batting average was a run-in with Yankees shortstop Phil Rizzuto. In Game Three, on a hit-and-run that failed, Stanky was thrown out by at least 15 feet, but when Rizzuto, covering second, leaned over to tag him out, Stanky kicked the ball out of his glove. The ball dribbled into center field, and Stanky scrambled to third. The play kept a Giants rally going and ignited a five-run outburst that won the game.

In December 1951 the St. Louis Cardinals sent pitcher Max Lanier and outfielder Chuck Diering to the Giants for Stanky, who assumed the position of player-manager for the Cardinals. Just a year removed from one of his best seasons ever, and still in his prime, Stanky began to remove himself from the playing field, appearing in just 53 games in 1952 and 17 in 1953.

Stanky tried to manage the same way he played: uncompromisingly and smartly. He tolerated no laziness and had fines for players not in the dugout for the first and last pitch of the game, not advancing runners, and similar infractions. He feuded with players who resented his strict style of play, with umpires whose calls he disagreed with, and with the media, who, for the first time it seemed, weren’t on his side. The Brat was almost dictatorial. “The men will play up to the fullest of their capabilities. . . . I do not plan to let anyone take advantage of me. . . . I am not a martinet and I am not a sucker.”12

Stanky’s method seemed to work. He was The Sporting News’ Manager of the Year in 1952, when the Cardinals went 88-66 and contended for much of the season. In 1953 the club finished in third place for the second straight year. Eddie was no longer an active player in 1954, a year in which the Cards faltered and finished in sixth place. Unpopular with his players, Stanky’s days in St. Louis were numbered. “He wanted you to play as if today’s game was your first or your last,” said one of his players, shortstop Dick Schofield.13 Stanky was unable to realize that the way that he had played was not the way that he could manage.

The end came just 36 games into 1955, with the Cardinals mired in fifth place. Beer magnate August A. Busch Jr., the Cardinals’ new owner, had “decided that Stanky was too much foam and not enough body,” and replaced him with Harry Walker on May 28.14

The Brat had learned much from his mentors, but what he never seemed to learn was that players of the 1950s would never be unquestioningly obedient and that “discipline should be laced with understanding,” as columnist Arthur Daley of the New York Times put it. Stanky grimly remarked that he would “stay in baseball . . . even if I have to go to a Class D league.”15

Stanky took a job managing the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. The Millers finished in fourth place, and again Eddie was out of a job. He wanted to return to the Giants as a coach, and had the blessing of club president Horace Stoneham, but the Giants’ pilot, Bill Rigney, said no. Instead, Stanky took a job as a coach for the Cleveland Indians under freshman manager Kerby Farrell. He remained there for two years.

Eddie did well in his role as a coach with the Indians. He tried to be a loyal organization man. He taught Indians hitter Bobby Avila the “intentional foul” that had made him such a successful player in his day, and stayed on when Farrell was replaced by Bobby Bragan, and then again when Bragan was replaced by Joe Gordon. Future major-league manager Joe Altobelli, who was a part-time first baseman on that Cleveland team, called Stanky the best third-base coach he ever saw.16

Ultimately, Indians ownership cleaned house, and Stanky left the club at the end of 1958. He returned to the Cardinals as a special assistant to general manager Bing Devine, where his role consisted of scouting and evaluating major- and minor-league talent. Devine was fired by the Cardinals in 1964 and moved on to become GM of the Mets. Stanky joined him in New York, but did not stay there long, as he was quickly hired by the Chicago White Sox to be their manager for the 1966 campaign.

Stanky’s predecessor in Chicago, Al Lopez, was a gentle, soft-spoken man who had been popular with his players. Lopez treated his players with kid gloves; Stanky rode them and pushed them to be the best they could. Lopez played percentage-driven, orderly baseball that rarely employed aggressive plays like the hit-and-run and delayed steals. Stanky was the exact opposite, managing the same way he had played. By 1960s standards, his methods were almost incomprehensibly aggressive. Where most teams never used more than 60 pinch-runners in a season, Stanky used 144 in 1966 and 127 in 1967.

Unable to adjust to their new run-and-gun style, the White Sox finished the 1966 season in fourth place. But by the start of the 1967 season, Stanky had fired many of the coaches he had inherited in 1966, and installed those he thought would help convey his philosophy to the players. Stanky’s forceful managing, able pitching staff, and a solid fielding team that made few mistakes helped keep the White Sox competitive deep into one of baseball’s most gripping seasons.

Embroiled in a battle with Boston, Minnesota, and Detroit for first place, Stanky’s pitching-rich team was going strong in late August, tied with the Red Sox for first despite being one of the league’s weakest-hitting clubs. Eddie had his players motivated and playing way over their heads, but barely anyone seemed to notice. Because of their lack of fireworks on offense and inconsistent clutch hitting, the White Sox were called dull. Hometown fans, who should have been coming to the ballpark in droves to see the hustle-filled baseball that the South Siders were playing, instead stayed away.

On August 13, after a tough game in Minnesota which Chicago lost, 3—2, on a controversial call in the ninth, Vice President Hubert Humphrey waited outside the clubhouse to meet with the team. He ended up waiting there for a long time while Stanky talked to his players. “Humphrey can’t hit,” said Stanky. “What do I need with him?”17

The Brat later apologized to Humphrey for making him wait, but the incident was indicative of his single-mindedness when it came to his team. Still, despite it all, the White Sox went into the last week of the season seemingly World Series-bound. NBC came to Comiskey Park to set up cameras. To win the pennant, the White Sox would have to beat the lowly Athletics in Kansas City and then the eighth-place Senators. But they lost a doubleheader to Kansas City, and then were shut out by the Senators, eliminating them from contention. The White Sox finished in fourth place, three games behind the champion Red Sox.

Notwithstanding the massive letdown that was the end of the 1967 season, Stanky’s contract was renewed for four years by White Sox owner Arthur Allyn for the “outstanding managerial job he did in the greatest American League race in history.”18

But the White Sox lost their first ten games in 1968, and 69 games later, Stanky was asked to resign—replaced, ironically, by former manager Al Lopez. That last partial season was excruciatingly painful. Toward the end of his tenure, Stanky was so frustrated with the White Sox’ inability to produce runs that after a third straight loss by one run, he instituted a $5 fine for players who failed in certain clutch situations. It didn’t matter; the White Sox finished the season in eighth place.

Back home in Alabama, Stanky secured the coaching job in 1969 at the University of Southern Alabama. After the relative glamour of the major leagues, college ball was different. “I had played in beautiful parks with beautiful locker rooms,” he said. “At Southern Alabama, I inherited a rock pile for a ball field, with no dugouts, a four-foot-high fence around it and no grass in the infield.”19 Stanky transformed that little school into a great college baseball team. For the next 14 years, beginning in 1969, teams led by Stanky went 488-193. He did not have a single losing season.

Best of all, Eddie finally changed his win-at-all-costs philosophy. He adopted an “everyone plays” style. “I’m a believer in participation,” he said. “The one record I care about came in a game against Vanderbilt in 1971. I played 38 men in one nine-inning game. Everyone got in. Some seasons, I’ve carried as many as 45 players on a team.” Stanky loved coaching students, and later said the biggest thrill was when his players graduated and “their mothers come up and embrace me for helping along their sons. There is something about a mother’s tears at graduation. I can’t weigh it.”20

Stanky sent 43 of his players to the major leagues, as his team became a Sun Belt Conference powerhouse. “He brought the University of South Alabama from just about point-zero to a national power in three years,” said a successor as coach, Steve Kittrell, who played under Stanky.21

There was a brief moment in the midst of his years at Southern Alabama where it seemed as though Stanky would resume his major-league managerial career. On June 23, 1977, he became manager of the Texas Rangers, and piloted them to a 10—8 victory. The next day, he quit. He told team president Eddie Robinson, “I can’t take the job . . . I’m homesick for my family.” Greeted by reporters back at the University of South Alabama, he was asked if he was back for good: “You’re damn right I am,” he responded.22

Stanky weathered a heart attack and open-heart surgery to coach the school for another six years before retiring in 1983. In one of his last games, Eddie showed a flash of his “Brat” persona, being thrown out of the contest for cursing an umpire. “If there is anything I can’t stand,” he said after the game, repeating one of his favorite sayings, “it’s an umpire who doesn’t know the rules.”23

On June 6, 1999 Eddie Stanky died in a hospital in his hometown in Fairhope, Alabama, after a heart attack. He was 83. Stanky was survived by his wife, son, three daughters, and eight grandchildren.

Sources

Kaese, Harold. The Boston Braves, 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004).

Rains, Rob. Cardinals: Where Have You Gone? (Champaign IL: Sports Publishing, March 2005).

Skipper, John C. A Biographical Dictionary of Baseball Managers (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2003).

New York Times

Ocala (Florida) Star-Banner

Philadelphia Inquirer

Sport

The Sporting News

Time

Wilmington (North Carolina) Morning Star

Notes

1 1920 U.S. census, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, Ward 33 Philadelphia, Enumeration District 1104, p. 17B, dwelling 353, family 356, Frank Stankiewicz; digital images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed 20 January 2011); from National Archives microfilm publication T625, roll 1625.

2 “The Brat,” Time, April 28, 1952, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,816375,00.html.

3 Arthur Daley, “A Day for Eddie Stanky,” Sports of The Times, New York Times, September 8, 1946.

4 Ibid.

5 Peter Golenbock, Bums (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984), 160.

6 Jonathan Eig, Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007) as quoted by Luther Spoehr in his May 7, 2007 review written for the History News Network (http://hnn.us/roundup/entries/38544.html: accessed 20 January 2011).

7 Frank Fitzpatrick, “The Ground Ball that Changed America,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 8, 2007. Stanky was one of Robinson’s first defenders, most notably firing back at hecklers on the Philadelphia Phillies bench during the early weeks of Robinson’s season. See also William Nack, “The Breakthrough,” Sports Illustrated, May 5, 1997.

8 Roscoe McGowen, “Southworth Picks Stanky to Play at Second Base for Braves Today,” New York Times, October 6, 1948, 38.

9 As quoted in Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves, 1871—1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 278.

10 John Drohan, “Stanky Says He Had Billy’s Approval for Hit-and-Run,” Sporting News, August 3, 1949.

11 “The Brat,” Time, April 28, 1952.

12 Ibid.

13 John C. Skipper, A Biographical Dictionary of Major League Baseball Managers (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003).

14 “Relaxed Redbird,” Time, June 13, 1955.

15 Arthur Daley, “Quick Harvest,” Sports of The Times, New York Times, June 6, 1955.

16 Dave Anderson, “Hot Seat at the Hot Corner,” Sports of The Times, New York Times, December 4, 1980.

17 “No Need for Mombo, or Hubert Humphrey,” Ocala (Florida) Star-Banner, August 25, 1967.

18 “Stanky is Given 4-Year Contract,” New York Times, October 1, 1967.

19 “Eddie Stanky, ex-player and manager, dies,” Wilmington (North Carolina) Morning Star, June 7, 1999.

20 Colman McCarthy, “Infielder Eddie Stanky, 82, Dies — Called the Brat for Canniness,” Washington Post, June 8, 1999.

21 “South Alabama Jaguars Hall of Fame.” University of South Alabama Athletics. University of South Alabama, n.d., accessed October 18, 2014.

22 “‘Homesick’ Stanky Resigns,” New York Times, June 24, 1977.

23 “Stanky to Retire,” New York Times, May 8, 1983.

Full Name

Edward Raymond Stanky

Born

September 3, 1915 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

June 6, 1999 at Fairhope, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.