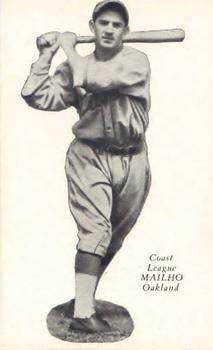

Emil Mailho

In his long and accomplished baseball career, San Francisco Bay Area native Emil “Lefty” Mailho managed over 2,500 hits, yet all but one — a pinch single in a 1936 contest — came in the minor leagues. One writer described Mailho as “arguably the best .056 lifetime hitter the majors (have) ever seen.”1 Mailho, who crossed paths with such all-time greats as Joe DiMaggio, Connie Mack, Babe Ruth, and Lefty O’Doul, was never able to gain a toehold in “The Show,” but was a star outfielder in the Pacific Coast League and the Southern Association in the 1930s and ’40s. A go-to source of reminiscences for Coast League historians in his later years, he was one of the oldest living former major leaguers before his death in 2007 at the age of 98.

In his long and accomplished baseball career, San Francisco Bay Area native Emil “Lefty” Mailho managed over 2,500 hits, yet all but one — a pinch single in a 1936 contest — came in the minor leagues. One writer described Mailho as “arguably the best .056 lifetime hitter the majors (have) ever seen.”1 Mailho, who crossed paths with such all-time greats as Joe DiMaggio, Connie Mack, Babe Ruth, and Lefty O’Doul, was never able to gain a toehold in “The Show,” but was a star outfielder in the Pacific Coast League and the Southern Association in the 1930s and ’40s. A go-to source of reminiscences for Coast League historians in his later years, he was one of the oldest living former major leaguers before his death in 2007 at the age of 98.

Mailho was born in Berkeley, California, on December 16, 1908, to Pierre Mailho, a grocer, and his wife, Marie, both from the Pau region of southwestern France. Emil was the second oldest of six children (five boys), and grew up playing baseball at Berkeley’s San Pablo Park, where many other big leaguers (including Hall of Famer Chick Hafey, Augie Galan, and Billy Martin) also cut their teeth on their way to Berkeley High and then the majors.2 Mailho attended the University of California, Berkeley, beginning in 1928 and pitched and played outfield for the Bears under coach Carl Zamloch for two seasons while studying architecture. One of Mailho’s memorable moments from his time at Berkeley was watching Roy Riegels’ infamous wrong-way run in the 1929 Rose Bowl.3

In 1930 Zamloch, who had left Berkeley to become manager and part-owner of the Oakland Oaks, recruited the 5-foot-8, 160-pound Mailho to play professionally. The Great Depression was taking hold, and he couldn’t pass up the chance to earn some money.4 “I might have been an architect now,” Mailho said in a 1968 interview. “But, oh, well, I don’t regret it.”5

Mailho didn’t stick with the Oaks, but was sent for more seasoning to Phoenix in the Class-D Arizona State League. His impressive numbers there — a .328 batting average in 1930 and .363 in 1931, highest on the team — earned him a return to the Bay Area, where he appeared in 10 games with the Oaks late in the 1931 campaign.

Thanks to his success in Phoenix, Mailho was expected to compete for a starting job in Oakland in 1932. Despite his diminutive size, noted the Oakland Tribune, “count on the half-pint outfielder to attract more attention in camp than will a lot of the big fellows.”6

It wasn’t easy: In the midst of the Depression, veteran players weren’t necessarily eager to help up-and-coming youngsters like the left-handed-batting, left-handed-throwing Mailho show their stuff in training camp. “When I was a rookie, they wouldn’t let me hit,” Mailho said. “They were protecting their jobs, afraid you’d take their job.”7 Nevertheless, he became the Oaks’ center fielder, hitting .316 in 135 games in 1932. In 1933 Mailho played in 180 of his team’s 192 games and batted .303, with 209 hits. Though stolen-base totals weren’t kept as an official statistic, he and his teammates ran with abandon — so much so that Mailho earned another nickname, “Fast Mail.”8

“Ray Brubaker was a good manager,” Mailho said of the Oaks’ skipper that year. “He liked to do a lot of running. We had Frenchy Uhalt, Leroy Anton, myself. We stole a lot bases — our club didn’t have a lot of power, so we had to. We drove the catchers nuts.”9

The Oaks expected big things from the 25-year-old Mailho in 1934, but a home-plate collision in an early April game left him with a knee injury that would sideline him for almost two months.10 Unable to play, he made good use of the time off, as he eloped to Reno with the former Lola Silva of Berkeley.11

Mailho eventually returned to the diamond in 1934, but managed only a .198 average in 96 at-bats. The lost season was a bitter disappointment to Mailho, who had hoped a big year would vault him to the majors.12 But, healthy again in 1935, he got off to a sizzling start, hitting .433 in April.13 At midseason, his average was a still-robust .364, good enough for third in the Coast League, and the Oaks were battling for first place for the first time in several years.14

Around this time, a group of Oaks fans worked with the club to organize Emil Mailho Day in honor of the popular outfielder.15 In what Mailho later characterized as his greatest thrill in baseball, on July 21, 1935, the second game of a Sunday doubleheader was dedicated to him.16 After receiving a variety of gifts from the team, Mailho proceeded to pound out five hits — four for extra bases — in a storybook performance.17 Although the Oaks faded from contention in August and September, Mailho saw continued success at the plate, finishing with a .353 average and 230 hits in 172 games. At season’s end, he made at least one sportswriter’s Coast League all-star team along with another Bay Area outfielder, Joe DiMaggio of the San Francisco Seals.18 Then, in October, Mailho received the news he’d been hoping for: The Philadelphia Athletics drafted him from the Oaks.19

Mailho reported to the Athletics’ training camp in Fort Myers, Florida, intent on not only securing a roster spot but also winning regular playing time. “The big league is faster than the Pacific Coast circuit in that the pitching is better and the defense snugger, but I feel I have the skill to stay in the fast set,” he said.20 His chances were improved by the scarcity of established major-league talent on the club: After a disappointing 1935 campaign, manager-owner Connie Mack had sold the last well-known members of Philadelphia’s 1929-1931 World Series teams –Jimmie Foxx, Doc Cramer, and Eric McNair — to the Red Sox. Sportswriter John Lardner saw fit to satirize the situation in a profile entitled “Mack Has Difficulty Recognizing [His] Players.”21

Things got off to a promising start for Mailho in the Athletics’ very first spring-training game, against the Cincinnati Reds. The contest drew 793 paying customers, one of whom was a recently retired big-leaguer named George Herman “Babe” Ruth.22 With the greatest slugger of all time looking on, Mailho launched a long home run off Si Johnson. “Nice hit, kid,” said Ruth.23

Mailho continued to play well throughout camp, and secured his roster spot by rapping five hits in a 19-0 A’s victory over the minor-league Newark Bears.24 But as soon as the club headed north to begin the regular season, he found himself in an unfamiliar position: at the end of the bench. Mailho was used almost exclusively as a pinch-hitter, a role he struggled with. “That pinch-hitting is tough,” he said. “I was used to being in there every day on the coast. And it’s a lot different.”25 In his first major-league at-bat, Mailho pinch-hit on Opening Day and struck out against Wes Ferrell of the Red Sox. He made outs in his next two pinch-hitting appearances as well before drawing a walk from Johnny Broaca of the Yankees and scoring on Wally Moses’ triple in a game on April 21. For the next four weeks, Mack continued to use Mailho intermittently as a pinch-hitter, and Mailho continued to struggle, drawing an occasional walk, but failing to hit safely.

On May 15, Mailho pinch-hit in the seventh inning with runners at first and second and the A’s trailing Detroit by a run. The situation called for a sacrifice, but he twice bunted foul. Things worked out for the best, however, as he lined a two-strike single to right off Tommy Bridges of the Tigers, that year’s league leader in wins and strikeouts.26 It was Mailho’s first (and as it turned out, his last) major-league hit. He ended up scoring the winning run on a single by Rabbit Warstler, helping the A’s post a rare road win.

As Philadelphia quickly settled into last place in the American League, Mack refused to start Mailho, or even to give him playing time in their many lopsided losses. Why? One theory had to do with Mailho’s size. “My uncle could hit, and he was fast, but he was short. Connie Mack was tall, and he didn’t like short guys,” said Mailho’s nephew, Tim Mailho.

Regardless of the reason, Mailho grew increasingly frustrated. “My uncle finally said, if you aren’t going to play me, trade me, or I’ll quit,” nephew Tim said. Mack optioned Mailho to Atlanta, but said he would be recalled later in the season.27 At the time of his demotion, Mailho was hitting .056, with one hit in 18 at-bats, although he had worked five walks and scored five runs.

Emil and Lola (along with newborn son Bobby) headed south to Atlanta, where Emil found himself immediately penciled into the starting lineup. He made a good first impression. “The new French center fielder of the Crackers gave the fans an idea of his ability last night by getting two hits, driving in a run and scoring himself, and making several fine catches,” reported the Atlanta Constitution after one of Mailho’s early efforts.28 A week later, after he went 7-for-10 in an Atlanta doubleheader sweep, the headline read: “Mailho Is Star.”29 In his half-season, he hit .315 and helped lead the Crackers to the Southern Association pennant.

At season’s end, the Athletics announced that they would recall Mailho in 1937.30 For the next couple of months, references to Mailho in the Atlanta sports pages were mostly in the context of the gap his departure would leave in the outfield. It turned out, though, that the Crackers still had designs on him. Team President Earl Mann, on his way back from the minor-league owners’ meeting in Montreal in December, made a stop in Philadelphia and purchased Mailho’s rights from Connie Mack.31 It was as close as Mailho would ever get to returning to the big leagues.

Mailho signed his contract with the Crackers in February 1937 and declared: “I hope to have my best year in baseball.”32 He got off to a fine start, hitting in 14 straight games in the early going.33 By June he had a .398 average. “[T]he fiery French rightfielder … is setting a burning pace among Southern League hitters,” noted the Atlanta Constitution. “He hopes to be back in the majors next season.”34 Mailho faded in the second half, but still finished with a .344 average, good for third in the batting race.

In 1938 Crackers catcher Paul Richards was named player-manager, his first opportunity as a skipper in what would turn out to be a long managerial career. As noted in his SABR biography, Richards was ahead of his time in appreciating the importance of nontraditional statistics like on-base percentage. Thus he was well aware of the value that Mailho — who walked often in addition to regularly topping .300 in batting average — brought to the Crackers’ lineup.

With Mailho hitting at a .304 clip with power (10 homers) and speed (21 steals) despite being hampered for much of the season with a leg injury, Atlanta reclaimed the Southern Association crown in 1938. The Mailhos also celebrated the birth of their second son, Gary, that summer. At season’s end, future Hall of Famer Burleigh Grimes, manager of the Montreal Royals of the International League, tried to pry Mailho loose from the Crackers, but Richards refused to deal him.35

In 1939 Mailho got off to another torrid start and was hitting over .400 well into June. Still, he drew no interest from a big-league team. Jack Troy, a sports columnist for the Atlanta Constitution, didn’t understand it. “Mailho can do everything well. He has a strong, accurate arm; he is a steady, dependable hitter, and … a fine base runner,” wrote Troy. “… [I]t’s a break for the Crackers that he didn’t fill the big league bill in the astute eyes of Connie Mack. But everyone is entitled to a mistake and it may not be too late yet to rectify the one made on Mailho.”36

After battling some midseason injuries, Mailho finished fifth in the league in 1939 with a .343 batting average, and led the league in walks and hit-by-pitches (for an on-base percentage of .472) as well as runs scored with 122.37 He continued to be immensely popular with Atlanta fans. They appreciated “the dazzling Frenchman,” and the feeling was reciprocal.38 “He loved Atlanta — my aunt loved it, too,” said Tim. “He was a sharp dresser, and the local store owners were always giving him fancy clothes. He loved that. And the food, too: When my aunt and uncle were old and I’d shop for them, my aunt always made me get chicory. That was something that they’d gotten a taste for in Atlanta.”39 Before the final regular-season game at Ponce de Leon Park, Mailho was voted the most popular Cracker and received a trophy.40

In March of 1940, Richards named Mailho as the Crackers’ field captain.41 Joining him in the outfield that year was young slugger and future three-time major-league All-Star Willard Marshall. Perhaps because of the presence of a bona-fide power hitter behind him, Mailho put together his best season. He hit .364, good for second in the Southern Association, while leading the circuit with 304 total bases and 144 runs scored.42 He also walked 121 times.43 In recognition of his outstanding campaign, Mailho was named the co-recipient of the league’s Most Valuable Player award (with catcher Greek George).44

Sports columnist Troy continued to struggle with the notion that Mailho wasn’t worthy of another shot in the majors. “Mailho is the mystery ballplayer of the Southern league,” he wrote. “For years he has been considered by writers and managers as the league’s finest all-around outfielder. … Why Mailho hasn’t gone up is still a puzzle.”45

Mailho got off to his typical hot start in 1941, hitting .375 through late May, but then was laid low by a bout of arthritis that kept him out of the lineup for a couple of weeks. When he returned, he slumped, and he finished with a .298 average, the first time in his career that he hit under .300 for a full season, though the Crackers again won the Southern Association crown.

In the fall there was some speculation that Mailho would be tapped to succeed Fred Lindstrom as manager of the Knoxville Smokies, but instead the Crackers announced that Mailho had been sold to the Oakland Oaks. “In making the deal, President Earl Mann respected the wishes of Mailho, who is nearing the end of a fine playing career and prefers to be near his California home,” said the Atlanta Constitution.46

It was with Oakland in 1942 that Mailho was in the middle of an unusual incident in Portland that resulted in the game being postponed, as recounted in a 1994 book. “Oaks outfielder Emil Mailho had just caught a flyball to end the inning. He was jogging in from the outfield when he disappeared! Mailho’s weight caused the ground to collapse under him into a sinkhole. The only thing visible was the top of Mailho’s cap.”47

Unfortunately for Mailho, his power also did a vanishing act in 1942, as he managed only one homer in 599 at-bats to go with his still-solid .297 batting average. Mailho blamed at least part of his power outage on the low-quality baseballs used during wartime. “The ball we hit was like a rock because they couldn’t use good rubber in them. It was all synthetic rubber, so the ball didn’t have any life in it.”48

Throughout the war years, Mailho was working a defense job during the day and playing baseball at night. “We worked at the Hubbell Galvanizing Plant while we were at home. … Of course, when we went on a road trip, we didn’t have to work. Les Scarsella, Cotton Pippen, and about five or six of us were there.”49

Mailho got his average back up to .314 in 1943, but in 1944, at age 36, he managed only a .277 mark. He also got into a spat with the team owner that caused the Oaks to cut him loose. “In 1944, Brick Laws (the Oaks’ owner) sold me to the Seals,” he said. “I had a little squabble with his son, Bill. He was clowning around in the dugout, and I had a bad inning and said, ‘get the hell out of here.’ Oh, geez, it hit the fan! Laws said, ‘He can’t call my kid names like that and get away with it.’ So that was the end of it. Dolph Camilli was the manager, and he said to Laws, ‘Are you going to let a little thing like that get in the way of the best hitter you have?’ When I went to the Seals, I killed the Oaks. All the Oakland guys were for me.”50

Wearing the uniform of his longtime rivals and playing for instead of against veteran Seals manager Lefty O’Doul, Mailho led the league in hitting for much of the 1945 season before slumping, though he still finished with a .306 average in 149 games. In December, the Seals sold him to Oklahoma City in the Texas League. Far from home, he played in only 55 games in 1946 before calling it quits and returning to the Bay Area. His career line in the minor leagues: a .318 average with 2,511 hits.

Mailho had been interested in construction ever since his childhood, when he helped his father remodel some apartments owned by the family.51 He obtained his contractor’s license in 1947, and, as with baseball, he was good at it. “He was a master carpenter and a bricklayer, too,” said Tim. “Whatever he did, he did to the full extent. He didn’t do anything halfway.”52

For the next 20 years, Mailho built custom homes in the Bay Area. In the late 1960s he closed his contracting business and briefly opened a boat-building operation near San Jose. A 1968 feature in the San Jose Mercury News profiled his painstaking construction of the 34-foot sloop Ne Libre (Born Free). The article reinforces the notion that Mailho was a perfectionist in everything he did.53

Mailho subsequently worked for several cities as a building inspector, including Fremont, where he also ended up building his own home. In retirement, he regularly participated in Coast League reunions and gave interviews to Coast League historians, but as his old friends and teammates died and his own health began to decline, his baseball past was at risk of being forgotten. When he was well into his 90s, however, Mailho was interviewed by Oakland A’s broadcaster Marty Lurie for a segment on Lurie’s “Right Off the Bat” pregame show. The interview revived the connection between Mailho and the franchise he’d played for — however briefly — and culminated with him being asked at age 97 to throw out the ceremonial first pitch before an A’s game in 2006. Mailho, his mind still razor-sharp, saw the irony in being honored on the mound at the Oakland Coliseum. “Emil told me, ‘I don’t want to throw out the first pitch (today), I want to hit it,’ ” said Tim.54

Mailho died a few months later at age 98 on March 7, 2007, in Castro Valley, California. He had been the fourth-oldest living former major-leaguer at the time of his death.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author utilized Baseball-Reference.com. The author would also like to thank Tim Mailho for his assistance and generosity.

Notes

1 George Rose, One-Hit Wonders: Baseball Stories (iUniverse, 2004), 10.

2 “Berkeley Park Produced Galaxy of Sports Stars,” Oakland Tribune, October 16, 1994; “Oaks Launched Careers of Baseball Legends,” Oakland Tribune, July 24, 1994. The latter article notes that Emil Mailho’s younger brother, Pete, also played for the Oakland Oaks, and that his little brother Johnny played semipro ball.

3 Author interview with Tim Mailho, September 24, 2018.

4 Ibid.

5 “When He Makes Hit Now — It’s a Boat,” San Jose Mercury News, June 24, 1968.

6 “Emil Mailho Signs Contract With the Oaks; May Become Regular,” Oakland Tribune, February 13, 1932: 10.

7 Dick Dobbins, The Grand Minor League (Emeryville, California: Woodford Press, 1999), 194.

8 Tim Mailho interview.

9 Dick Dobbins, 194.

10 “Mailho Injury Sends Jakucki to Centerfield,” Oakland Tribune, April 11, 1934: 22.

11 “Oak Fielder Takes Bride,” Oakland Tribune, July 2, 1934: 17.

12 “Pool Again Denied Raise, Spurns Offer,” Oakland Tribune, February 5, 1935: 18.

13 “Mailho Clouts at .433 Clip,” Oakland Tribune, April 30, 1935: 25.

14 “Oaks 2 Games from Top, Battle for Lead,” Oakland Tribune, July 9, 1935: 18.

15 “Vitt Banished by Umpire; Oaks Win 10-Inning Battle,” Oakland Tribune, July 13, 1935: 8.

16 “Oaks Launched Careers of Baseball Legends,” Oakland Tribune, July 24, 1994.

17 “Oaks Take Series from Angels, Head for Portland,” Oakland Tribune, July 22, 1935: 12.

18 “The Sports X-Ray,” Los Angeles Times, September 17, 1935: 30.

19 “Mailho, Oaks Fielder, Drafted by Athletics,” Oakland Tribune, October 16, 1935: 12.

20 “Tips from the Sports Ticker,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 22, 1936: 46.

21 “Mack Has Difficulty Recognizing Players,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), March 19, 1936: 13.

22 “A’s Hopefuls Lose Camp Opener to Reds, 10-7,” Camden (New Jersey) Courier-Post, March 7, 1936: 24.

23 “At 97, Feisty Mailho is 2nd Oldest Living Athletic,” East Bay Times (Contra Costa, California), August 13, 2006.

24 “Five Out of Five,” Columbus Telegram, March 27, 1936: 6.

25 “Mailho Looms as a Tough Batter,” Atlanta Constitution, June 11, 1936: 19.

26 “3-Run Flare-Up in 7th Brings A’s 2nd in Row,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 16, 1936: 15.

27 “Athletics Farm Out Mailho to Atlanta,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 8, 1936: 17.

28 “Crackers Take Baron Opener, 4-2; Lindsey Hurls Today,” Atlanta Constitution, June 13, 1936: 10.

29 “Crackers Take Double-Header from Little Rock, 7-3, 12-1,” Atlanta Constitution, June 20, 1936: 11.

30 “Macks, Dodgers Recall Mailho, Pitcher Leonard,” Atlanta Constitution, September 18, 1936: 18.

31 “Purchase of Leonard Sets Hurling Corps,” Atlanta Constitution, December 18, 1936: 22.

32 “Emil Mailho Signs Contract; 13 Crackers Are Now in Fold,” Atlanta Constitution, February 12, 1937: 22.

33 “Mailho Stopped at 14 Straight,” Atlanta Constitution, May 7, 1937: 25.

34 “Fiery French Outfielder Sets Burning Pace in Southern League Hitting,” Atlanta Constitution, June 6, 1937: 17.

35 “All in the Game,” Atlanta Constitution, December 9, 1938: 23.

36 “All in the Game,” Atlanta Constitution, June 12, 1939: 13.

37 “Haas Officially Wins Southern Batting Crown,” Atlanta Constitution, October 31, 1939: 19.

38 “They’re the First Five Hitters in Cracker Lineup,” Atlanta Constitution, March 10, 1938: 16.

39 Tim Mailho interview.

40 “Crackers End Regular Season with 7-6 Victory,” Atlanta Constitution, September 11, 1939: 13.

41 “Emil Mailho Named Captain of Crackers,” Atlanta Constitution, March 10, 1940: 20.

42 “Mailho’s Greatest Season Gives Him 2d Place in Batting Race,” Atlanta Constitution, September 15, 1940: 18. Baseball-Reference.com shows him with 304 total bases.

43 “Dejan Official Batting Champ at .371,” Atlanta Constitution, November 20, 1940: 18.

44 southernassociationbaseball.com/timeline.pdf.

45 “All in the Game,” Atlanta Constitution, September 11, 1940: 22.

46 “All in the Game,” Atlanta Constitution, December 6, 1941: 16.

47 Dick Dobbins and Jon Twitchell, Nuggets on the Diamond (Emeryville, California: Woodford Press, 1994), 203.

48 Dick Dobbins, The Grand Minor League, 194.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid., 262-63.

51 “When He Makes Hit Now — It’s a Boat,” San Jose Mercury News, June 24, 1968.

52 Interview with Tim Mailho, October 12, 2018.

53 “When He Makes Hit Now — It’s a Boat.”

54 “At 97, Feisty Mailho Is 2nd Oldest Living Athletic.”

Full Name

Emil Pierre Mailho

Born

December 16, 1908 at Berkeley, CA (USA)

Died

March 7, 2007 at Hayward, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.