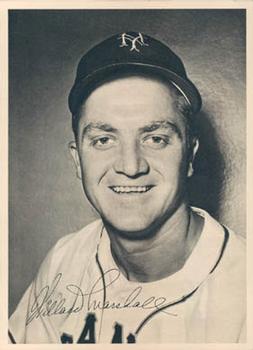

Willard Marshall

The New York Giants were known as the “Windowbreakers” when they smashed the single-season record for home runs in 1947. Leading the assault were the four big bats in the middle of the lineup: Johnny Mize with 51 homers, Willard Marshall with 36, Walker Cooper with 35, and Bobby Thomson with 29.

The New York Giants were known as the “Windowbreakers” when they smashed the single-season record for home runs in 1947. Leading the assault were the four big bats in the middle of the lineup: Johnny Mize with 51 homers, Willard Marshall with 36, Walker Cooper with 35, and Bobby Thomson with 29.

Marshall, the left-handed hitting right fielder, was just 26 that summer. The New York Mirror’s Ken Smith said he “appears to be destined for a long career as one of the Giants’ greats.”1 But Marshall never found that power stroke again, although he was a productive hitter for several years. Late in life he reflected, “I could never figure out why I couldn’t do it again.”2

Willard Warren Marshall was born on February 8, 1921, in Richmond, Virginia, the younger of two children of Joseph W. Marshall, a farmer, and the former Agnes Sterne. Though he lived most of his adult life in New York and New Jersey, Willard called himself “an ol’ country boy.”3 He grew up on a farm and never lost his genteel Southern accent that would have sounded right at home sipping mint juleps on a verandah.

When he was 16, his mother drove him to a St. Louis Cardinals tryout camp. Scout Eddie Dyer was so impressed that, before the day was over, he persuaded Mrs. Marshall to sign a contract on behalf of her son. But when they got home, Pa blew his stack. He tracked down Dyer at a hotel and ordered him to tear up the contract.

Willard played semipro ball around Richmond and entered Wake Forest College in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Willie Duke, an outfielder for the Southern Association Atlanta Crackers who lived nearby, spotted the young slugger and recommended him, but Marshall turned down Atlanta’s offer. Duke kept after him, and scout Nap Rucker raised the bonus offer to $3,500. Midway through his sophomore year in 1940, Marshall gave in and signed.4

The Class A-1 Southern Association (equivalent to the present Double A) was fast company for a 19-year-old with no professional experience, but the 6-foot-1, 195-pound youngster proved to be a spring training sensation. The Atlanta Constitution’s Jack Troy described him as “a natural-born distance hitter.”5 Playing primarily in right field, Marshall hit .314 in his rookie year and his modest 14 home runs were the most on the team. In 1941, he improved his production to 21 homers and 106 RBIs. The Crackers, an independent team with no major-league affiliation, looked to sell him for a profit.

The Brooklyn Dodgers were ready to buy—until December 7, 1941. When the United States entered the world war, Marshall, almost 21 and unmarried, was prime draft bait. The Dodgers backed off. The Crackers continued shopping him until just before spring training. The best deal they could find was with the Giants, who agreed to try the young man on a make-good basis. They would pay Atlanta $30,000, plus a player, if they kept him.

Marshall’s bat immediately caught the attention of new manager Mel Ott, and the club wrote a check. “I came up just as the Giants were coming to the end of their salad days in the 30s,” Marshall remembered.6 After winning pennants in 1933, ’36, and ’37, the team had declined steadily and was coming off two straight losing seasons. Manager Bill Terry had resigned, leaving the job to Ott, who was still the regular right fielder and the Giants’ main power source.

The jump from Atlanta to New York was a culture shock for the 21-year-old “country boy.” An Atlanta teammate, Charlie Glock, wrote to his family in New Jersey asking them to take care of the newcomer, and Marshall spent many of his off-hours with the Glocks.

Ott installed the rookie in left field on Opening Day in 1942. In the season’s second game, facing Kirby Higbe of the archrival Dodgers, he belted a grand slam into the upper deck in the Polo Grounds’ short right field to give the Giants their first victory. A game-winner to beat the Dodgers made him a fan favorite. He went on to hit six home runs in the first 29 games.

In July Ott pulled him aside and told him, “Son, you’ve made the All-Star team.”

“I said, ‘Are you kidding?’ He said, ‘No, congratulations.’”7 The only rookie on the NL team, Marshall grounded into a force-out as a pinch-hitter.

His first season was at best a qualified success for a 21-year-old. His early power surge didn’t hold up; he finished with 11 home runs, batting .257 with a .679 OPS, slightly better than the league average. By September Marshall had more on his mind than National League pitchers. He enlisted in the Marine Corps and reported for duty after the final game.

Marshall spent most of the war stateside in a quartermaster unit. While the Army and Navy created several super-teams of former and future major leaguers to play for bragging rights and entertain the troops, the Marines, the smallest of the armed forces, had no such all-star team. Major Dan Topping, soon to be co-owner of the New York Yankees, got permission to put together a squad of the best available players and take them to Hawaii and other Pacific island bases to play in tournaments against the other services. Marshall was chosen for the team and was at Pearl Harbor when the war ended in August 1945.8

He was still waiting for his discharge when spring training opened in 1946. Finally released on April 2, he went home to Virginia for a family visit, then joined the Giants when they came through Richmond on their barnstorming tour. On April 16 he was in the Opening Day lineup, slightly overweight and still getting his land legs back after the long sea voyage home.

Playing primarily in center and left field, Marshall started slowly and was batting .229 at the All-Star break. Then he took off, hitting over .300 in the second half to raise his final average to .282 with a .733 OPS and 13 homers.

It was that year that Dodgers manager Leo Durocher said of Ott and the Giants, “Why, they’re the nicest guys in the world! And where are they? In last place!”9 In sportswriter shorthand, that boiled down to “Nice guys finish last,” and Durocher liked it so much he made it the title of his memoir. The Giants? They finished last.

Marshall succeeded Ott as the right fielder in 1947, and Ott became a bench manager. He had been one of the most popular players and the greatest slugger in franchise history. Without him in the lineup, his team became the greatest slugging aggregation the game had ever seen.

The Giants’ 1947 home-run surge should not have shocked anyone because their horseshoe-shaped park was the National League’s friendliest for long-ball hitters. “Everybody was a home run hitter in the Polo Grounds,” Marshall said.10 The layout rewarded pull hitters with the right field seats a comical 258 feet from the plate and left field only 280 feet (250 to the overhanging second deck) before the walls sloped away to a vast center field nearly 500 feet deep.11 The Giants usually led the league in homers, but the 1947 outburst of 221 was nearly 40 more than any team had hit before (the 1936 Yankees had hit 182). The Giants hit 131 at home, 90 on the road.

“Just one of those deals where everybody was hitting home runs,” Marshall reflected. “I don’t know why.”12 There was no obvious explanation; if the ball was livelier, the authorities didn’t acknowledge it. The Giants were not alone. The other seven teams in the National League hit 51 percent more four-baggers than the year before. The Big Bang of 1947 was a sign of things to come in the 1950s, when home runs exploded in both leagues.

Giants secretary Eddie Brannick dubbed the team “the Windowbreakers.”13 Mize, Marshall, and Cooper, slotted 4-5-6 in the lineup, were called “the Three Musketeers.” Against left-handed pitchers, the right-handed Cooper moved up to fifth between the two lefty batters. The trio finished in the league’s top five in homers (along with Thomson) and RBIs, and in the top 10 in OPS and wins above replacement (WAR) for position players.14

Mize’s league-leading 51, tied with Ralph Kiner, was not out of context in his career; he hit 40 or more in two other seasons. But Cooper never approached 35 again, and Marshall never again came close to 36; his next-best total was 17. “When I came up, I was a dead pull hitter,” he said decades later. “Even if they pitched me outside, I could pull the ball. But all of a sudden I just lost it.”15

In his career year, Marshall scored 102 runs and drove in 107 while batting .291 with an .894 OPS (134 OPS+). He had more home runs than strikeouts (30, about once in every 22 plate appearances), as did Mize.

The Giants rose to fourth place with an 81-73 record despite one of the league’s worst pitching staffs. They finished 13 games behind the pennant-winning Dodgers, but that was a lot better than last.

Ott and owner Horace Stoneham made no significant moves to improve the pitching during the winter. By midseason in 1948 the club had fallen one game under .500 at 37-38 when the unthinkable happened. Ott was fired and Leo Durocher of the hated Dodgers succeeded him as manager of the Giants.

“Everybody in those days hated Durocher” because of his belligerent personality, Marshall remembered. The historic bitter rivalry between the two teams fanned the hatred. Durocher to the Giants? “Nobody could believe it,” Marshall said. “We were amazed.”16

The club improved slightly under the new manager to finish 78-76, in fifth place. Marshall fell off to just 14 homers with a .272 batting average. Third baseman Sid Gordon replaced him as a power threat with 30 homers. Marshall and Gordon had become unlikely close friends—an “ol’ country boy” from Virginia and a Brooklyn Jew.

With the Giants going nowhere in September, Durocher gave Marshall a day off to get married. His bride was Marie Antoinette Bruni of Palisade, New Jersey, who worked in her father’s real estate agency and took over the business after he retired.

Durocher assessed the team he had inherited in four words: “Back up the truck,” he told Stoneham.17 The Giants, lacking speed, pitching, and defense, were not Durocher’s kind of team. The “windowbreakers” didn’t impress him. Besides, many of them were nice guys. But the owner refused to approve a drastic makeover. Stoneham liked to watch those long balls fly out of the Polo Grounds.

When Durocher kept nagging him, Stoneham gave the go-ahead to dispose of Mize and Cooper during the 1949 season. After the club stumbled to a 73-81 record, Durocher got his way. At the December major-league meetings, he shipped Marshall and Gordon along with Buddy Kerr, a shortstop residing in the manager’s doghouse, and pitcher Sam Webb to the Boston Braves for a new double-play combination, Eddie Stanky and Alvin Dark. They were Durocher’s kind of players. Dick Young of the New York Daily News wrote that he “traded a major portion of the famed Polo Grounds punch for a flash of speed and a dash of fire.”18

Marshall was coming off an outstanding performance in 1949: a .307 batting average and .401 on-base percentage, both career highs, with an .830 OPS. Fans chose him as the starting right fielder in the All-Star Game. But he hit only 12 homers and drove in just 70 runs, below par for a middle-of-the-order hitter, and he did not have the speed to make up for the lack of power. He did, however, have a reputation as a nice guy. Marshall wasn’t surprised when Durocher traded him. “I know I was not his kind of ballplayer,” he said, “and he got rid of me as soon as he could.”19

When Durocher discussed the deal, he said Gordon was the only one he would miss.20 “He knew what he was doing,” Marshall observed. “He got what he wanted, and he went on and won a couple of pennants.”21 The Giants edged out the Braves for third place in 1950 and won pennants in 1951 and 1954, though the emergence of Willie Mays had a bit to do with that.

Braves manager Billy Southworth was counting on his two new outfielders to provide some badly needed power. Sid Gordon delivered, but Marshall sank into a slump soon after Opening Day in 1950 and lost his regular job. As a pinch-hitter and backup outfielder, his .235 batting average was the worst of his career, but, remarkably, he struck out only five times in 336 plate appearances, once in every 68 times up. Marshall’s ability to make contact had always been excellent; in 1950 it was almost perfect in spite of the poor results.

Tommy Holmes replaced Southworth in midseason 1951 and put Marshall back into the lineup. He rediscovered some of his punch with a .281 average and .784 OPS, but just 11 home runs. In right field, he was perfect—or, at least, error-free. He played 123 games in the field without making an error all season, only the second outfielder to record a fielding percentage of 1.000, after the Phillies’ Danny Litwhiler achieved the mark in 1943. Despite his lack of speed, Marshall was recognized as an outstanding defensive outfielder throughout his career. “I always said if I could get to it, I could catch it,” he said.22 His arm drew raves for strength and accuracy. A right-handed thrower, he led NL right fielders in assists four times and was in the top three for seven straight years. Teammate Johnny Mize said, “He can practically dot an ‘i’ with the ball.”23

Another change of managers in 1952 ended Marshall’s stay with the Braves. The club was falling toward a seventh-place finish in its final year in Boston when Charlie Grimm replaced Holmes on May 30. The Braves instituted a youth movement, and the 31-year-old Marshall was sold to Cincinnati in June.

The Reds hadn’t enjoyed a winning season in seven years and seemed to have a long-term lease on sixth place, except when they finished seventh. Marshall went into the everyday lineup in right field but batted only .267 with a .723 OPS.

In 1953 the Reds shortened Crosley Field’s right field foul line and lowered the fence, turning their left-handed hitters into sluggers.24 First baseman Ted Kluszewski had his first 40-homer year and new center fielder Gus Bell hit 30. Marshall, sharing right field in a platoon with Bob Borkowski, contributed 17 homers, his biggest output since 1947, in just 400 plate appearances while batting .266 with an .824 OPS. But the club didn’t budge out of sixth place. After the season general manager Gabe Paul traded Marshall to the Chicago White Sox for three players, none of whom stuck with the Reds.

The Sox manager, Paul Richards, had managed the young Marshall in Atlanta, but he had no room for the veteran Marshall in his Chicago lineup. Consigned to pinch hitting and an occasional fill-in in the outfield, Marshall contributed next to nothing in 1954 and 1955. In June ’55 the White Sox released him and offered him a job as manager of their Class-B farm club in Waterloo, Iowa. He finished out the season there but declined to return for a second year.

The Giants took Marshall on as a scout covering New Jersey and New England. He represented the team on the after-dinner circuit, handing out trophies to Little Leaguers and speaking at father-son gatherings. He also worked for his wife’s family real estate business. Beginning in the 1960s, he served for 25 years as director of recreation for the city of Fort Lee, New Jersey, before retiring.

Willard and Marie raised two daughters, Debra and Lesley. The family lived for more than four decades in the Palisades section of Fort Lee, next door to Marie’s parents, with a postcard view of the Manhattan skyline across the Hudson River. Willard served on the board of directors of a local savings and loan and filled his later years with celebrity golf tournaments, autograph shows, and fantasy camps. He was 79 when he died on November 5, 2000, still searching for his missing home-run stroke.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Notes

1 Ken Smith, “Go for Four, Marshall Plan for Giants,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1947: 3.

2 Willard Marshall interview by Brent Kelley (undated), SABR Oral History Collection. Hereafter “SABR interview.”

3 Willard Marshall interview by William J. Marshall, September 13, 1985, Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries. https://nunncenter.net/ohms-spokedb/render.php?cachefile=1985oh209_chan102_ohm.xml. Hereafter “UK interview.”

4 UK interview.

5 Jack Troy, “Two Cracker Outfield Positions Open,” Atlanta Constitution, March 13, 1940: 16.

6 UK interview.

7 Rich Marazzi, “Batting the Breeze,” Sports Collectors Digest, January 12, 1996: 90.

8 UK interview. This is how Marshall remembered the way the marines’ team was formed.

9 Frank Graham, The New York Giants (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952), 268.

10 UK interview.

11 Dimensions according to the Seamheads database: http://www.seamheads.com/ballparks/.

12 UK interview.

13 Fred Stein, Under Coogan’s Bluff (Glenshaw, Pennsylvania: Chapter and Cask, 1978), 127.

14 WAR calculated by baseball-reference.com.

15 Marazzi, “Batting,” 90.

16 UK interview.

17 Leo Durocher with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975), 237.

18 Dick Young, “Giants Get Stanky, Dark in 6-Player Deal,” New York Daily News, December 15, 1949: C20.

19 UK interview.

20 Young, “Giants Get Stanky, Dark.”

21 UK interview.

22 SABR interview.

23 Unidentified clipping in Marshall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

24 Seamheads database.

Full Name

Willard Warren Marshall

Born

February 8, 1921 at Richmond, VA (USA)

Died

November 5, 2000 at Norwood, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.