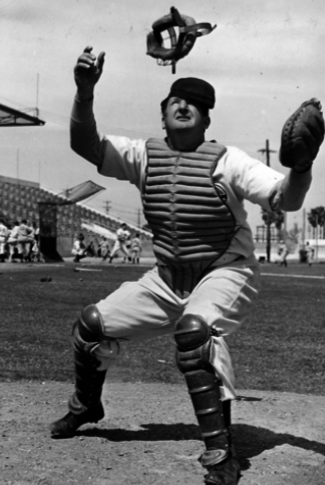

Ernie Lombardi

It is one of those records that may never be equaled, much less broken. For 75 years a handful of pitchers have come close to tying Johnny Vander Meer’s record of pitching two consecutive no-hitters. But it has proven elusive for even the most elite hurlers throughout major-league history.

It is one of those records that may never be equaled, much less broken. For 75 years a handful of pitchers have come close to tying Johnny Vander Meer’s record of pitching two consecutive no-hitters. But it has proven elusive for even the most elite hurlers throughout major-league history.

His first no-hitter came on June 11, 1938, at Crosley Field, Vander Meer’s home ballpark in Cincinnati. Many games of this variety require great defense and timely hitting. Cincinnati’s left-handed hurler was the beneficiary of both against the opponent, the Boston Bees. In the fourth inning Vander Meer walked right fielder Gene Moore, one of his three walks that day. The next batter was Johnny Cooney. The hit-and-run play was on. Cooney popped out to catcher Ernie Lombardi. Moore was steaming toward second base, and then tried to scamper back to the first-base bag, but he was doubled off when Lombardi alertly threw to first baseman Frank McCormick to complete the double play. In the fifth inning Vander Meer walked Tony Cuccinello. Lombardi made a snap throw to first base and caught Cuccinello leaning toward second base. “Lom would pick about six to seven guys a year off first base, throwing side-arm behind left-handed hitters,” said Vander Meer. 1

But the Reds backstop was not through. With the home team clinging to a lead of a single run, Lombardi connected for a two-run home run in the bottom of the sixth inning. It provided the final margin of victory in the 3-0 Reds win. It was just another day at the office for the lumbering catcher.

Vander Meer next toed the rubber on June 15 against the Brooklyn Dodgers, the first night game at Ebbets Field, and in New York City. Vander Meer was not as sharp on this night; he walked eight Dodgers, three in the ninth inning to load the bases with one out. A force out at home plate accounted for the second out, and Leo Durocher’s line out to center fielder Harry Craft ended the game. Vander Meer etched his name in major-league history with the 6-0 victory and his second consecutive no-hitter.

Home-plate umpire Bill Stewart was as close to the action as one could get without having to purchase a ticket. He offered a different perspective on the game. “Give some credit to Lombardi,” said Stewart. “Sure, Vander Meer had to pitch perfectly to get his no-hitters. But what about the guy who told the kid what to pitch? If Lombardi had guessed wrong on one hitter, if he had called for a fastball when a curve was the smart pitch, Vander Meer never would’ve made it. Lombardi’s judgment was just as perfect and just as important as Vander Meer’s pitches.”2

Ernesto Natali Lombardi was born on April 6, 1908, in Oakland, California. He was one of four children born to Mr. and Mrs. Domenic Lombardi. Ernie had three sisters, Stella, Rena, and Rose. Domenic Lombardi emigrated from Italy and owned a small grocery store. Ernie was a common sight to customers, working at his post behind the counter.

Lombardi, who would grow to be 6-feet-3 as an adult, was taller than most children around his age. He spent much of his time playing sandlot baseball at Bay View Park. When he was 12, he played for a semipro team, Ravoli’s Meat Market. Coaches took notice of Lombardi’s strong arm, and his career as a catcher began. A scout from the Oakland Oaks tried to sign Ernie but the youngster refused because he did not want to leave the Bay Area to play for one of Oakland’s farm clubs. However, after a short stint running the grocery store while his father was away, Lombardi changed his mind and contacted the Oaks. He realized that he might prefer a career in professional baseball over that of a grocer.

After a brief stop in Ogden, Utah, Lombardi honed his craft back home in Oakland. From 1928 through 1930, he smoked the ball in Pacific Coast League parks, posting batting averages of .377, .366, and .370. His defensive ability was also supreme. He registered an amazing 95 assists in 1929 and topped that mark with 102 in 1930.

Lombardi possessed some distinctive physical characteristics, including a pair of huge hands and a bigger-than-normal nose. There is a picture of Lombardi holding seven baseballs in one hand. His nose was said to be just as enormous. “They first began kidding me about the nose and calling me ‘Schnozz’ back in the Coast League,” he said. “But the funny thing was, I didn’t get too much razzing from the bench jockeys. Mostly, it came from the fans.”3 Lombardi was good-natured about the kidding he received, and often showed off a self-deprecating humor of his own.

The Brooklyn Dodgers sent Hank DeBerry, Eddie Moore, and $50,000 to Oakland for Lombardi on January 19, 1931. Brooklyn skipper Wilbert Robinson favored seasoned veterans over green kids, which left Ernie the bench watching Al Lopez handle most of the catching chores. But Lombardi produced when he was given the opportunity, hitting .275 in 43 starts at catcher. He demonstrated a strange batting grip in which he clamped his left index finger over the little finger of his right hand. It is the same grip a golfer employs, although Lombardi never once stepped on the links. Apparently, the grip worked just dandy for him.

Lombardi’s stay in Brooklyn was short, and on March 14, 1932, he was part of a six-player deal that sent him to Cincinnati. He started instantly with the Reds, batting over .300 in six of his first seven seasons there. Although Lombardi had success at most of the venues in the National League, he seemed to thrive at the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia.

Lombardi enjoyed some of his biggest career days at the Philadelphia bandbox, at the expense of the Phillies. On May 8, 1935, he tied a league record with four doubles in a game as the Reds pasted the Phils, 15-4. On May 9, 1937, Lombardi became the second Red to tally six hits in a nine-inning game. In a 21-10 shellacking of the Phillies, Ernie stroked two doubles, drove in five runs, and scored three runs.

Between 1932 and 1937 Cincinnati finished in the cellar four times and the manager seat was more like a carousel. Bill McKechnie came to the Queen City and took the reins before the 1938 season. “I liked to play for Bill,” said Lombardi. “He was quieter than other managers. But all he had to do was look out at you over the top of his glasses and you’d know you’d done something wrong.”4

“Deacon Bill” guided the Reds to a fourth-place finish in 1938, his first year at the helm. That was just a preview of coming attractions. One reason for the Reds’ sudden surge in the standings was Lombardi. Although he had been a starter since being acquired from Brooklyn, Lombardi finally received some notice for his abilities when he led the circuit that season with a .342 batting average. He smashed 19 home runs, had 95 RBIs, and hit 30 doubles. He was the starting catcher for the National League team in the All-Star Game. (On the negative side, Lombardi set a National League record for the most double plays hit into in a season with 30. The record stood for 70 years until Houston’s Miguel Tejada broke it in 2008.) Lombardi was honored by both the Baseball Writers Association of America and The Sporting News as the National League’s Most Valuable Player.

As the double-play mark suggests, one aspect missing from Lombardi’s skill set was speed. Although he was a smart baserunner, he was not a fast one; in fact, he is widely recognized as one of the slowest runners in baseball history. It was often said that Lombardi doubled to left and beat out a single. However, Lom hit rifle shots, and there were no cheap hits in his arsenal. Many times infielders would station themselves on the grass behind the dirt infield. The joke was that the opposing team’s insurance policy would not cover all the potential damage caused by Ernie’s hitting ability.

Behind the plate, however, Lombardi was as agile as they come. He possessed a strong throwing arm and moved with ease to catch pop flies around home plate. He was so skilled that sometimes he looked almost nonchalant working behind the dish.

The Reds won the pennant in 1939 and 1940. Bucky Walters won 49 games and Paul Derringer 45 in the two seasons to lead a solid staff. “You could sit in a rocking chair and catch them guys,” said Schnozz. 5 In contrast, Lombardi felt that Vander Meer was hard to catch because he was a hard thrower and erratic. You could never tell where the ball was going to end up. Once Pepper Martin of St. Louis was on third base, dancing around in an attempt to distract Vander Meer. His strategy worked, and Vander Meer uncorked a pitch way outside. Lombardi just reached for the ball with his bare hand and snagged it. “Listen, if you’re going to sit back there and catch me barehanded, the least you could do after you throw the ball back to me is shake your hand a little like I had something on the pitch,” Vander Meer told Lombardi. “You’re making me look bad.”6

It is unfortunate, even unfair, that a player can be best remembered for one single play in his career. Ernie Lombardi is one such player. On October 8, 1939, at Crosley Field, the Reds and New York Yankees were playing Game Four of the World Series. The Yankees held a commanding 3-0 lead in the Series, and were looking to sweep the Reds. But the Reds would not bow, and the game was tied, 4-4, heading into extra innings. Walters, pitching in relief, walked Frank Crosetti to lead off the tenth. After a sacrifice, Charlie Keller reached on an error by shortstop Billy Myers. Joe DiMaggio laced a shot that fell in front of right fielder Ival Goodman. Goodman bobbled the ball, and by the time he threw home, Crosetti had scored the go-ahead run and Keller was making his way to the plate. Keller crashed into Lombardi, who fell back and lost control of the ball. Lombardi lay sprawled out on the ground behind the plate, the ball lying two feet away. DiMaggio kept coming toward home. Ernie regained his senses, grabbing the baseball in a futile attempt to tag DiMaggio. But the runner slid over the catcher’s hand, and was called safe. The play was referred to as “Lombardi’s Snooze.” The Yankees wrapped up the Series with the 7-4 victory. The next year at spring training, Keller denied that he had touched Lombardi, and that the big catcher had just fallen backward.

“Ernie was wronged,” recalled Joltin’ Joe. “He WAS knocked out in a collision with Charley Keller, who scored, and I saw immediately that something was haywire. I kept running and never stopped. Keller gave Ernie more than just a bump, as they described it. He put Ernie out of commission.”7 Vander Meer had a different take on the play. “The throw from the outfield came in a short hop and hit Lom in the cup. You just don’t get up too quick. Somebody put out the word that ‘Lombardi went to sleep, took a snooze.’ He was paralyzed. He couldn’t move. Anybody but Lombardi, they would have had to carry him off the field.”8 Bucky Walters said, “It was a silly rap. But the Yankees beat us four straight and they had to pick on something, I guess. You can blame part of the thing on me. I was pitching, and I should have been behind home plate, backing up Lombardi. But the run didn’t mean anything, anyway.”9

The 1940 season offered a different climax. Powered by a 23-8 record in September, the Reds coasted to their second pennant in a row. They had 100 wins, besting second-place Brooklyn by 12 games. But Lombardi badly sprained his right ankle on September 15 at Brooklyn. His season was over, and when it was time for the World Series, backup Jimmie Wilson caught most of the games, with Lom able to catch in only one. Behind two wins each from Walters and Derringer, the Reds topped the Detroit Tigers in seven games.

In Lombardi’s ten years with the Reds, he hit over .300 in seven. By all accounts he was a terrific teammate and a good-hearted person. Like most people, he had his peculiarities. He did not believe in signing autographs. It wasn’t until a youngster asked if he was illiterate that Lombardi, to dispute the point, signed the scrap of paper.

Lombardi towered over many of the other players, and was somewhat of a gentle giant. However, there were instances when he could get riled. Tony Cuccinello was a prankster and particularly apt at pulling off the hidden-ball trick. “There was a close play at second and I missed (Lombardi) sliding in. The pitcher was standing nearby. While Ernie’s getting up I told the pitcher to stay off the rubber. I had the ball in my glove. The pitcher went toward the mound, picked up the rosin bag and looked in at the catcher like he’s looking for the sign and Ernie walked off the bag. When I had enough room I ran over to him and showed him the ball. Oh, he was mad. He said to me, ‘You tag me and I’ll punch you right in the nose.’ I never tagged him. He just walked back to the dugout.”10

Lombardi’s batting average plummeted to .264 in 1941. Differences with general manager Warren Giles and the dramatic drop in his hitting prompted Cincinnati to sell Lombardi to the Boston Braves before the 1942 season.

The Braves, who were piloted by Casey Stengel, were an atrocious bunch. First baseman Max West was the leading power hitter with 16 home runs and 56 RBIs. Lombardi, in only 309 at-bats was credited under the rules of the day with leading the league in hitting with a .330 average. During a game with the Reds, Cincinnati catcher Ray Lammano told him, “Man, you’re driving McKechnie crazy with the way you’re hitting. He’s pulling his hair out.”11 Lombardi earned a spot on the National League All-Star squad.

Despite the fine year he had in Boston, Lombardi asked the Braves to trade him and held out until a deal could be completed. On April 27, 1943, he got his wish. He was dealt to the New York Giants for catcher Hugh Poland and infielder Connie Ryan. “To say that I’m highly pleased to become a Giant doesn’t adequately express my feelings,” said Lom. “I’ve had my eye on that left-field scoreboard in the Polo Grounds for a long time. Now, I’m going to see what can be done about it as a home-field target.”12

In 1944 Lombardi married Berice Ayers of Oakland, California. They had no children.

With World War II raging and many leading players in the armed forces, many of the major-league teams were filled with aging veterans or players who might still be in the minors under normal circumstances. Billy Jurges, Dick Bartell, and Joe Medwick had all seen better days, and player-manager Mel Ott was also past his prime. Others, like Mickey Witek and Johnny Rucker, had major-league jobs but saw their careers end shortly after the war ended. For Lombardi, whose Selective Service number was 4,541, the chances of being drafted seemed unlikely. He was called to take his draft physical in September 1943, but was turned down by the Army.

The playing field was balanced in the major leagues with many of the teams being forced to field patchwork lineups. The Giants were not competitive during this period, often placing in the second division. But on April 30, 1944, all of the Giants had their hitting shoes on as they thrashed the Dodgers, 26-8. Lombardi posted a career high with seven RBIs. In two of the three years he started for the Giants, Lombardi batted over .300. But before the 1946 season, with Lombardi aging, the Giants purchased Walker Cooper from St. Louis to assume the catching burden. Lombardi played two more years, retiring after the 1947 season. In 17 seasons, he had a career batting average of .306, with 190 home runs, and 990 RBIs. He returned to the Pacific Coast League and played one final year of professional baseball in 1948, with Oakland and Sacramento. In 2003 Lombardi was inducted into the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame.

Unfortunately for Lombardi, his life after baseball was not a comfortable one. He held different jobs on the West Coast, unable to settle into a steady profession. He lived the life of a recluse, still haunted by the “Lombardi Snooze” moniker. In April of 1953, he and his wife were visiting relatives in Castro Valley, California. Ernie used the bathroom, said he was not feeling well, and went to lie down in a bedroom. Bernice, his wife, checked on him a short time after and discovered that he had cut his throat with a razor he found in the bathroom. He struggled with emergency personnel, saying that he wanted to die. Lombardi was saved from his suicide attempt and entered a private sanitarium.

Year after year, Lombardi was passed over for entry into the Baseball Hall of Fame. The Veterans Committee also passed over Schnozz. Lombardi was disgruntled about his exclusion. He vowed that he would not attend the induction ceremonies even if he was elected. He re-entered the baseball world when he took a job as a press-box attendant at Candlestick Park in San Francisco. It was more of a public-relations position, but Lombardi loved to talk baseball, specifically about his playing days.

Lombardi died on September 26, 1977, after a long illness. He was survived by his three sisters. Bernice had preceded him in death in 1973. Lombardi finally received the call from Cooperstown, posthumously, in 1986. One of his peers, Birdie Tebbetts, a good catcher in his own right, had been elected to the Veterans Committee and led a personal crusade to get Lombardi elected. The “Snooze play” and Lombardi’s attempted suicide were major roadblocks. Lombardi was inducted into the Hall of Fame along with Bobby Doerr and Willie McCovey.

Lombardi was inducted into the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame in 1958. In 2004 a full-size bronze statue of Ernie was dedicated outside Great American Ballpark, joining those of Frank Robinson, Joe Nuxhall, and Ted Kluszewski at the entrance to the ballpark.

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Tebbetts, Birdie, and James Morrison, Birdie (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002).

cincinnati.reds.mlb.com/index.jsp?c_id=cin&tcid=mm_cle_sitelist

milb.com/content/page.jsp?sid=l112&ymd=20061214&content_id=148680&vkey=league3

Notes

1 James W. Johnson, Double No-Hit (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 3.

2 Lombardi’s Hall of Fame player file.

3 Jack Zanger, Great Catchers of the Major Leagues (New York: Random House, 1970), 125.

4 Zanger, 129.

5 Zanger, 131.

6 Norman L. Macht and Dick Bartell, Rowdy Richard (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1987), 319.

7 Art Rosenbaum, “One Out From Hall of Fame, San Francisco Chronicle, September 28, 1977.

8 Dave Kindred, “Ernie Lombardi a Bitter Recluse Because of ‘Snooze,’” Louisville Courier-Journal, February 8, 1977.

9 Kindred.

10 Macht and Bartell, 95.

11 Zanger, 134.

12 Lombardi’s Hall of Fame player file.

Full Name

Ernesto Natali Lombardi

Born

April 6, 1908 at Oakland, CA (USA)

Died

September 26, 1977 at Santa Cruz, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.