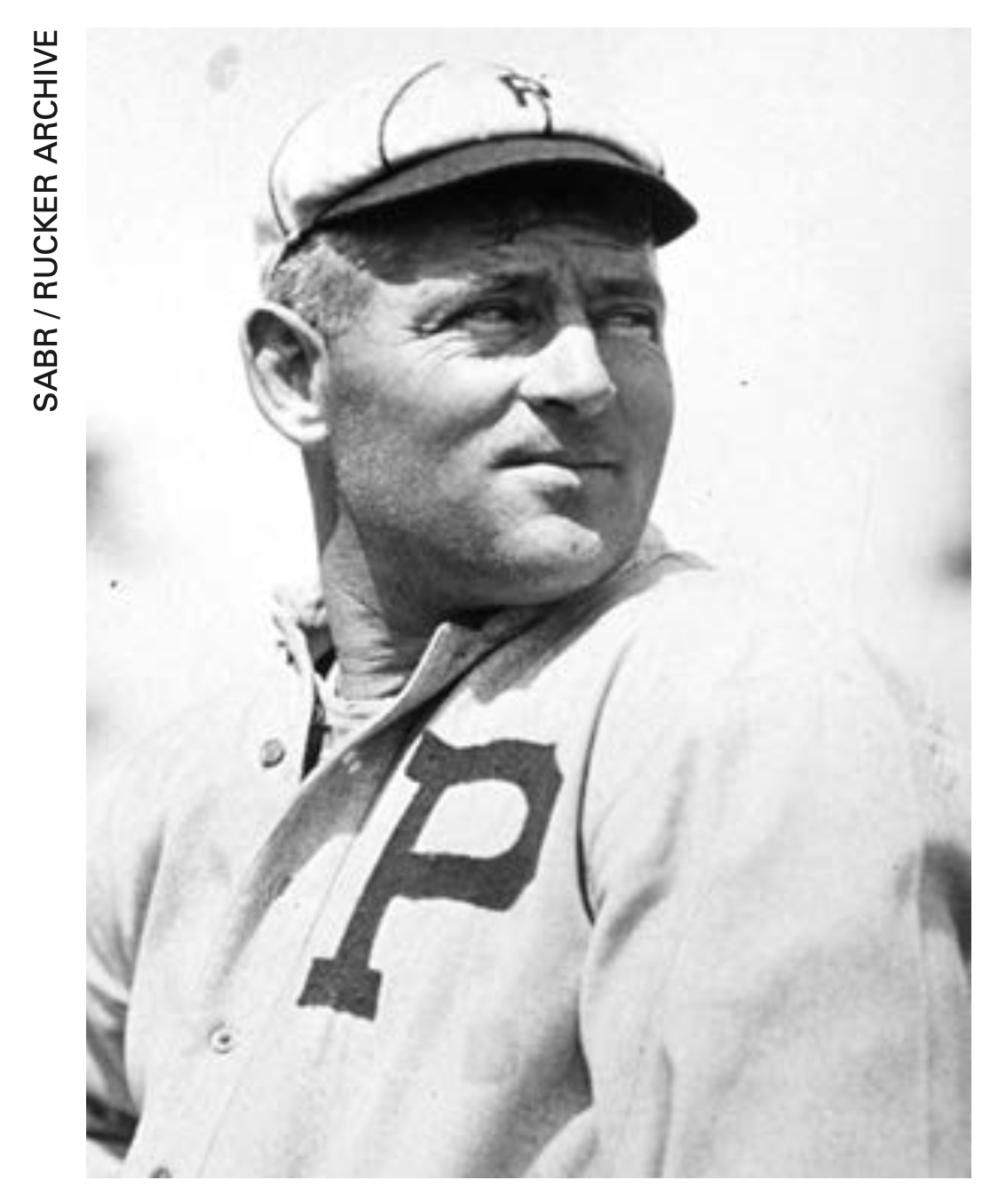

Gavy Cravath

Gavy Cravath was an anomaly in the Deadball Era. Employing a powerful swing and taking advantage of Baker Bowl‘s forgiving dimensions, the Philadelphia clean-up hitter led the National League in home runs six times, establishing new (albeit short-lived) twentieth-century records for most home runs in a season and career. In an era when “inside baseball” ruled supreme, Cravath bucked the trend and preached what he practiced. “Short singles are like left-hand jabs in the boxing ring, but a home run is a knock-out punch,” he asserted. “It is the clean-up man of the club that does the heavy scoring work even if he is wide in the shoulders and slow on his feet. There is no advice I can give in batting, except to hammer the ball. Some players steal bases with hook slides and speed. I steal bases with my bat.”

Gavy Cravath was an anomaly in the Deadball Era. Employing a powerful swing and taking advantage of Baker Bowl‘s forgiving dimensions, the Philadelphia clean-up hitter led the National League in home runs six times, establishing new (albeit short-lived) twentieth-century records for most home runs in a season and career. In an era when “inside baseball” ruled supreme, Cravath bucked the trend and preached what he practiced. “Short singles are like left-hand jabs in the boxing ring, but a home run is a knock-out punch,” he asserted. “It is the clean-up man of the club that does the heavy scoring work even if he is wide in the shoulders and slow on his feet. There is no advice I can give in batting, except to hammer the ball. Some players steal bases with hook slides and speed. I steal bases with my bat.”

Clifford Carlton Cravath was born March 23, 1881, in Escondido, California. His father, A. K. Cravath, became the first mayor of Escondido in 1888 and later sheriff of San Diego County during the 1890s. Young Cliff was the catcher on his high-school baseball team, but he is better remembered as captain of the football team. In 1898 Cravath and his fellow Escondido footballers lost the first-ever high-school gridiron match-up in the history of San Diego County, 6-0, to San Diego High School. Following graduation, Cravath scratched for a living as a fumigator, telegraph operator, and semipro ballplayer in San Diego and Santa Ana, where his family had relocated after the turn of the century.

It was during his semi-pro days that he gained the nickname “Gavy.” There are many stories about its origin, but it’s apparently a contraction for the Spanish word gaviota, which means “seagull.” During a Sunday game in the early 1900s, Cravath reportedly hit a ball so hard that it killed a seagull in flight. Mexican fans shouted “Gaviota.” The English-speaking fans thought it was a cheer and the name stuck. It’s pronounced to rhyme with “savvy,” so sportswriters of the period added an extra “v,” but Cravath himself spelled it G-A-V-Y. The Southern Californian also had another nickname, “Cactus” (because of his western background and prickly personality), but he apparently didn’t care for it and never included it in his signature.

Stories of Cravath’s potent bat quickly spread, and in 1903 the young slugger entered the professional ranks with the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. Playing initially in right field and later at first base, Cravath helped the Angels claim four pennants over the next five years. At the end of the 1907 season, based on his .303 batting average and 10 home runs, Cravath was selected team MVP and sold to the Boston Red Sox. He departed California for what was known out west as “the Eastern Leagues.” Isolation on the West Coast had already cost Gavy precious years; at 27 he was considered old for a major-league rookie.

Not fitting the mold of the stereotypical Deadball Era fly chaser, Cravath had difficulty breaking into a Boston outfield that soon became dominated by the fleet-footed Tris Speaker and Harry Hooper. Throughout his career Gavy remained sensitive about his relative lack of speed. “They call me wooden shoes and piano legs and a few other pet names,” he once said. “I do not claim to be the fastest man in the world, but I can get around the bases with a fair wind and all sails set. And so long as I am busting the old apple on the seam, I am not worrying a great deal about my legs.” Cravath was batting .256 with only a single home run (but 11 triples) when the Red Sox sold him to the Chicago White Sox in February 1909. A slow start in the Windy City in 1909 got him traded (along with sore-armed pitcher Nick Altrock and backup first-baseman Jiggs Donahue) to the lowly Washington Senators for Sleepy Bill Burns, a promising but corrupt pitcher who had posted a 1.70 ERA as a rookie in 1908.

Washington manager Joe Cantillon also was the owner of the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, and he sent Gavy to Minneapolis after the new outfielder went hitless in six at-bats for Washington. The 1910-11 Millers are now recognized as the outstanding minor-league team of the Deadball Era, and Cravath became the team’s biggest star. Learning to hit to the opposite field to take advantage of Nicollet Park‘s short porch (it was a lot like Baker Bowl, running 279 feet down the right-field foul line with a 30-foot fence), the right-handed hitting Cravath batted .327 with 14 home runs in 1910. The following year he led the Association with a .363 batting average, and his 29 home runs were the most ever recorded in organized baseball. At one point that season Cantillon threatened to fine Gavy $50 if he hit any more home runs over the right-field barrier; apparently he’d broken the same window in a Nicollet Avenue haberdashery three times during a single week.

But despite his impressive numbers, Cravath couldn’t escape the minors, a victim of the Deadball Era’s draft rules. It took a clerical error—the Millers inadvertently left out the word “not” in a telegram to Pittsburgh—to get Gavy back to the big leagues. In a controversial decision, the National Commission ruled that Minneapolis could not retain Cravath because of the mistake. The 31-year old slugger received his second chance at the majors in 1912 with the Philadelphia Phillies, who purchased his rights for $9,000. This time the more experienced Cravath proved that he belonged in the big leagues, batting a respectable .284 with 11 home runs and 70 RBIs in his first season with the Phillies. Displaying a strong, accurate arm, he also led NL outfielders with 26 assists.

Cravath’s greatest year in the majors arguably was 1913. Though that year’s Chalmers Award went to Brooklyn’s Jake Daubert, most historians agree that Cravath, who led the majors with 19 home runs, 128 runs batted in, and a .568 slugging average, was the NL’s true most valuable player. Gavy paced the circuit with 179 hits, placed second in batting average at .341 (behind only Daubert’s .350), and ranked third in doubles (34) and fourth in triples (14). His 128 RBIs established an NL record that wasn’t broken until Rogers Hornsby drove in 152 in 1922. Cravath followed up that performance with another solid campaign in 1914, batting .299 with 100 RBIs and winning the second of his six home-run titles with 19 circuit blows—all 19 of them hit at home. Defensively, he led NL outfielders again with 34 assists.

In 1915 Gavy Cravath smacked 24 home runs, a figure that established a 20th-century record and gave him as many as 12 of the other 15 major-league teams hit collectively that season. There’s no question that Baker Bowl’s cozy dimensions helped him do it. With a short left-field power alley and a right-field fence only 272 feet from home plate, Cravath took advantage of his home park as much as any other player in history; 79% of his 1915 home runs and 78% of his career four-baggers came at Baker Bowl. He led the NL in home runs hit at home seven times in his career but never turned the trick on the road; indeed, he never hit more than five on the road in any season. Despite those statistics, Gavy reacted defensively when commentators suggested that he owed his impressive home-run totals to Philadelphia’s short right field. “That right-field fence was never any farther away than it was when I joined the club,” he told F. C. Lane. “And while we are on the subject, let me make a point. That fence isn’t always a friend to the home-run slugger. I have hit that fence a good many times with a long drive that would have kept right on for a triple or a home run if the fence hadn’t been there. There are always two sides to every fence.”

Putting aside his 24 home runs, Cravath did much more in 1915 to help the Phillies win their first pennant in their otherwise dismal history. For the third time in his career he was the NL’s leading outfielder in assists (28), and he also led the league with 89 runs scored, 115 runs batted in, 86 bases on balls, and a .393 on-base percentage. In the 1915 World Series the Red Sox respected Cravath’s right-handed power so much that they didn’t pitch their young lefthander, Babe Ruth, who was coming off an 18-8 season. Gavy knocked in the deciding run in the Series opener at Baker Bowl but failed to drive in another run in the next four games as Philadelphia lost all four by a single run.

Cravath finished second in the NL home-run race in 1916, belting 11 to finish one behind Dave Robertson of the Giants and Cy Williams of the Cubs. Had he hit one extra long ball, he would have led the National League in home runs for seven consecutive years—a feat that was never accomplished until Ralph Kiner did it from 1946 to 1952. In 1917 Gavy tied Robertson for the NL lead with 12 home runs and placed second to young Rogers Hornsby in slugging average (.484 to .473) and triples (17 to 16). During the war-shortened 1918 season, it took only eight round trippers for Cravath to win his fifth home-run title, but he posted career lows in batting average (.232) and slugging percentage (.376).

Defying Father Time, the 38-year-old Cravath rebounded in 1919 to put together one last magnificent season. Playing just 56 games in the outfield, he won his sixth and final NL home-run crown with 12 fence-clearing blows in only 214 at-bats. (In the American League, meanwhile, Babe Ruth shattered the single-season mark Cravath had set in 1915 by blasting 29 circuit clouts.) Gavy also collected six hits (including two home runs) in 19 pinch-hitting appearances. “A good pinch-hitter is a valuable man to have on a ball club and can win a lot of games,” he said. “The thing which handicaps him is the fact that he is usually never called upon until late in the afternoon when the sun is lower and the ball correspondingly hard to see. Besides, he has had no opportunity to face the pitcher and size him up. For all that, I rather like to hit in the pinch.”

Midway through the 1919 season, with the team buried at the bottom of the NL standings at 18-44, the Phillies canned manager Jack Coombs. Cravath reluctantly agreed to take his place and guided the Phils to just 29 victories in 75 games over the rest of the season. Invited to return to the helm in 1920, Gavy played even less frequently than he had in 1919, though he still managed to lead the NL with 12 pinch-hits. The Phillies actually improved in 1920, finishing with a 62-90 won-lost record, but ended up in last again. When a sportswriter asked him about the grand jury investigation into an allegedly fixed late-season game in which his Phillies whitewashed the Cubs, 3-0, Cravath replied, “I don’t know why they gotta bring up a thing like this just because we win one. We’re liable to win a game anytime.”

But the wins weren’t frequent enough for the Phillies management, which released the nearly-40-year-old player-manager after the 1920 season. Cravath decided to retire as an active player, prompting sportswriter Robert W. Maxwell (the namesake for college football’s Maxwell Trophy) to proclaim, “Gavy is the greatest home run-clouter in the history of baseball and has piled up a record that might never be equaled.” Cravath’s 20th-century career home-run record of 119, however, was quickly shattered by Babe Ruth in 1921, and it stood as the 20th-century NL record only until 1923, when it was surpassed by Cy Williams.

Gavy Cravath managed the Salt Lake City Bees of the Pacific Coast League in 1921, then spent one year as a scout for the Minneapolis Millers, his last job in professional baseball. Returning to Laguna Beach, California, where for years he’d leisurely enjoyed his offseasons fishing the Pacific and accumulating property, he became active in the real-estate business. In September 1927 Cravath was elected judge, and for the rest of his life enjoyed saying that he claimed the gavel quite by accident. He and two friends didn’t like the sitting judge in Laguna Beach so they drew straws to determine which of the three would run against him. Gavy drew the short straw and won the election by an almost 3:1 ratio. Lacking any formal legal training, he claimed that he based his decisions on principles of sportsmanship he’d learned on the diamond.

Judge Cravath became known as a crusty jurist and stories abound from his years on the bench. Once, when two young robbers appeared before him and asked permission to join the armed forces as part of a probation sentence, Cravath said, “When I see a man in uniform walking down the street, I look at him with pride. You haven’t earned the right to wear such a uniform bearing the honor of our country. Six months in county jail.” On another occasion, Cravath asked a Santa Ana motorcycle cop if he was heading back to the station after a hearing. The officer replied in the affirmative. Next the town drunk staggered into the courtroom and Cravath said, “Pete, you hop on the back of George’s bike and he’ll take you up to the county jail for a few days to dry out.” No stranger to due process, Pete objected, “You can’t do that, Gavy. Hell, I ain’t even been arraigned yet.” Cravath glared at the drunk. “Now look here, Pete,” he growled. “You know you were drunk and I know you were drunk. Now we’re not going to waste any of the taxpayers’ money on a goddam trial. Get on that goddam motorcycle and go to jail for a few days to dry out.” Pete grinned sheepishly and obeyed the order.

Well-known and widely respected, Judge Cravath was reversed only twice during his 36-year tenure on the bench. When he finally died at age 82 on May 23, 1963, few Laguna Beach residents even realized that in a prior life, the Honorable Clifford C. Cravath had set major-league home-run records that it took the mighty Babe Ruth to break.

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Clifford Carlton Cravath

Born

March 23, 1881 at Poway, CA (USA)

Died

May 23, 1963 at Laguna Beach, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.