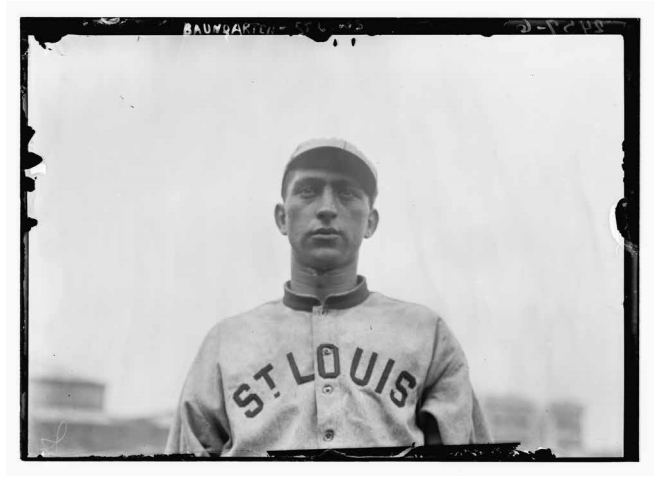

George Baumgardner

In many ways George Baumgardner could have become the hero of a kind of baseball fairy tale: He came to the St. Louis Browns in 1912 as a 20-year-old right-handed pitcher after playing only two seasons of Class-D ball in the mountains of his native West Virginia, someone who, the story goes, had honed his skills by throwing rocks at squirrels and who kept in shape by cutting wood.

In many ways George Baumgardner could have become the hero of a kind of baseball fairy tale: He came to the St. Louis Browns in 1912 as a 20-year-old right-handed pitcher after playing only two seasons of Class-D ball in the mountains of his native West Virginia, someone who, the story goes, had honed his skills by throwing rocks at squirrels and who kept in shape by cutting wood.

He also had considerable talent. His manager compared his fastball to Walter Johnson‘s and one writer said his curve “broke like a streak of lightning.”1 In his debut in April of that year, Baumgardner bested the Chicago White Sox and future Hall of Famer Ed Walsh 4-1, striking out seven and allowing only three hits. He was even better in his next outing, also against the White Sox, when he shut them out for 15 innings and struck out 10 in a game that ended in a 0-0 tie. Sportswriters across the country, including Grantland Rice, began predicting he would become one of the premier pitchers in the game.

However, whatever talent Baumgardner had, he was also what one writer called “the high nut” of baseball, someone who liked to jump onto and off moving trains, spontaneously hop on stage, uninvited, to sing in movie theaters and perform magic on street corners, and preferred his salary in $1 bills since it made him feel richer.2

For a few years, as long as Baumgardner seemed to possess promise, those stories were, for the most part, humorous asides to a career that seemed on the verge of greatness. In the end, however, his eccentricity got in the way of his ability and he became the butt of public jokes and cautionary tales. After a solid 1914 season in which he posted the only winning record of his career, 16-14, and helped the Browns to a respectable (for them) fifth-place finish, he came to camp for 1915 out of shape. The team sent him to Louisville in the American Association before the season was even a month old – or at least tried to, since he refused to report, choosing to go home to West Virginia rather than face the embarrassment of demotion to the minor leagues. He came back for 1916 but after eight innings over four games the Browns let him go. Baumgardner’s major-league career ended with a lifetime record of 38-49, his chief claim to fame being his inclusion in the ignoble club of pitchers who lost 20 games in a season when he went 10-20 in 1913.

George Washington Baumgardner was born on July 22, 1891, in Barboursville, West Virginia, then a village of around 400 people near the Ohio border, roughly 15 miles from Huntington. He was the second youngest of 10 children of Charles Baumgardner, a carpenter, and his wife, Frances, a laundress.3

If one is to judge by the newspaper accounts from Baumgardner’s time in baseball, he was generally perceived as a naïve country boy; his formal education ended after the seventh grade at Barboursville PS #2.4 One story described him as “not versed in the finer points of the world’s ways” and reported that he was so unschooled that he was never ever able to actually sign his name to his contracts but could only mark them with an “X.”5 (Although this last detail gives us insight into the way in which the press viewed Baumgardner, it is apocryphal as the Baseball Hall of Fame archives hold two contracts bearing his signature.6) Another story made much of the fact that Baumgardner never left his home state until he joined the Browns.7 Another reported that he perfected his pitching by throwing stones at squirrels, trying to kill them.8 Yet another mocked him for not knowing that the American League was one of two major leagues since, when a reporter asked his opinion of his opponent for his debut, Ed Walsh, he reportedly replied, “What I want to know … if this Walsh is such a great pitcher, why ain’t he drafted by the National League?”9 Still other stories made much of the fact that Baumgardner did not know he should eat the spears and not the stalks on a piece of asparagus and that when he bought a rubber raincoat in New York he was so fascinated by the novelty of it that he wore it even on sunny days.10

Despite his naїveté, Baumgardner was, by many accounts, a natural talent on the diamond.

While the records of his life in baseball before he joined the Browns are scarce, it appears that Baumgardner’s first professional experience was with the Huntington Blue Sox of the six-team, Class-D Virginia Valley League in 1910, playing under a manager named Cy Young. (Although many sources today report that the Hall of Fame pitcher helmed Huntington that year, at least one newspaper account from that time makes plain that the team’s skipper was actually a different person with the same name.11)

While the writer was not able to find Baumgardner’s statistics for that season – Baseball Reference, the Spalding and Reach guides, and the Baseball Hall of Fame archives offer only the final league standings but no individual records – brief game accounts throughout the season give evidence of his effectiveness. One reports Baumgardner struck out 14 in a July 4 game and “had [Ashland-]Catlettsburg at his mercy.”12 The following month, he recorded the only no-hitter in the league that season, also against Ashland-Catlettsburg; afterward, a reporter dubbed him the “premier twirler” for his team, which finished the year with the best record in the league.13 In October, Baumgardner faced major-league competition for likely the first time when the Pittsburgh Pirates came to Huntington for an exhibition game, but the Pirates “hit freely” against him, scoring eight runs on 14 hits, five of them for extra bases.14

Baumgardner stayed with Huntington the next year, as the Virginia Valley League added two teams and became the Mountain States League. Once again he pitched well; by mid-June his record stood at 11-1 – and he received more national attention for his one loss than he did for any of his victories, since newspapers across the country picked up the story because the defeat came in a June 8 game against Charleston in which he and opposing pitcher Dick Niehaus each tossed no-hit ball through 10 innings, Charleston finally winning in the 11th when Baumgardner gave up a run on three hits. A bit more than a week later, on June 18, on the recommendation of scout Billy Doyle,15 the Browns signed him to a contract for 1912.16 However, they allowed him to finish the season with Huntington.17 He ended the season leading the league in strikeouts (292) while finishing tied for the most victories (24) and for the fewest runs allowed per nine innings (1.98).

When Baumgardner first showed up for the Browns training camp before the 1912 season, the team reportedly had small expectations for him. He was young and by most accounts green, a 20-year-old right-handed pitcher with only two seasons of Class-D ball on his résumé. Though the official record lists him at 5-11 and 178 pounds, he reportedly gave the team the impression that he was frail.18 According to one account, the Browns did not allow him to him face any hitters until one day manager Bobby Wallace noticed the speed of his pitches as he threw to catcher Paul Krichell.19 Even as he took the mound to face Browns hitters in an intrasquad game, however, the team still remained skeptical as they had yet see him throw anything but fastballs. Team scout and former player Monte Cross said, “I was a little afraid he did not own a change of pace. He used a side arm delivery entirely and I feared he couldn’t control a curve ball.”20

In that workout, on March 22, however, Baumgardner turned in an outing that led the St. Louis Post-Dispatch to declare him the “newest sensation,” adding that he “monopolized the spotlight for a full half-hour and was the recipient of what was probably the most lavish praise ever heaped upon the head of a bush league pitcher.” According to the story, Baumgardner “served up the most deceptive assortment of breakers ever seen on the local diamond” as his teammates watched in awe.21 It was after this workout that Wallace compared him to Johnson.

Baumgardner made his major-league debut in the team’s fourth game of the season, against Chicago in White Sox Park on April 14, the same day the passenger liner Titanic struck the iceberg that sank it. Opposing him, Ed Walsh was already regarded as one of the premier pitchers in the game – he’d notched 100 victories over the previous four years – but on that Saturday afternoon, Baumgardner was, according to the Chicago Tribune, better, pitching “as neatly as Cy Young or Rube Waddell might have done it in their palmy days … [working] with splendid control … able to cut the ball across any portion of the plate except the middle.”22

In his next outing, the 0-0, 15-inning tie in his home debut six days later, also against the White Sox, his pitching again earned praise: “Baumgardner was a wonder. … His delivery is almost unfathomable. … And his control is excellent.”23 Newspapers across the country began talking about him with enthusiasm. The Washington Post declared Baumgardner “sensational”24 while the Arizona Republic suggested he was “the pitching sensation of the current baseball season.”25 Grantland Rice mentioned him in a column five days after the extra-inning tie game: “‘Fanatic’ suggests that we add Larry Cheney, of the Cubs, and George Baumgardner, of the Browns, to the list of budding slabmen with the stuff. Consider them added, with bells attached and the laurel tied on. Both have arrived and delivered.”26

Even when he lost eight of his next nine decisions, the press’s admiration for Baumgardner was not shaken as writers attributed his record more to the Browns’ inept play rather than his lack of ability. Referring to him as a “speed demon,” the Post-Dispatch wondered what his record would have been had he “been backed up [by] the [pennant-winning] Red Sox?”27 When he went 9-5 over the rest of the season, to close out 11-13, observers declared, “Great things are expected of George Baumgardner … next season.”28

However, the season also brought suggestions that Baumgardner’s eccentricity might get in the way of his ability: After his second start, the 0-0 15-inning game, he left the team for nearly three weeks. St. Louis newspapers explained his absence by saying he had gone back to West Virginia to take care of his mother, who had fallen ill.29 But a newspaper in West Virginia suggested that he had returned to Barboursville because he was homesick; the story reported he had his manager’s permission and that he would rejoin the Browns the following weekend to start against the Tigers.30 However, his next start would not come until nearly a week after that.

Later that year, on a road trip in Boston, Baumgardner missed the team train for New York. When he finally met up with the Browns, manager George Stovall, who had replaced Wallace on June 2, chided him for “loafing,” but Baumgardner defended himself, saying, “I got lost in that bloody town. Never saw so many crooked streets in all my life.”31 Stovall assigned outfielder Willie Hogan as Baumgardner’s keeper when the team was on the road.

When the season ended, Baumgardner went back home to Barboursville, where he bought his mother a house with money he’d set aside from his salary with the Browns. He performed a song-and-dance act to earn extra cash, while doing strength training by cutting trees.32

In January 1913, Baumgardner agreed to his contract with the Browns at what was reported as a “substantial boost” in his salary. When he returned it, Stovall predicted that he would “develop into one of the star pitchers in the … league,” saying that his speed and control would “combine with the experience he had gained the past year [and] he will prove a valuable man for the team.”33

Stovall’s projection that Baumgardner would be valuable to the Browns proved prophetic in a way, as he was something of a workhorse for a bad team. He led them in games started (31), innings pitched (253⅓) and complete games (23); all of those totals ranked among the top 10 in the league. His other statistics were not so good: he went 10-20 with a 3.13 ERA that was among the highest among American League pitchers with 200 or more innings. He also led the league’s hurlers in most hits allowed, 267.

Despite his record, Baumgardner became a prime target of the “outlaw” Federal League. The Browns fired Stovall as manager and, after he hooked up with the Kansas City Packers, he set his sights on acquiring the pitcher for the fledgling league. For the next year, the Browns and Packers engaged in a tug-of-war over the rights to Baumgardner. Starting in the fall of 1913, newspapers gave conflicting reports: Baumgardner had signed with the Packers; Baumgardner was “loyal” to the Browns.34 The conflict came to a head when Stovall, claiming Baumgardner had agreed to jump to the Federal League, threatened to go to court to seek an injunction preventing Baumgardner from playing for the Browns that season when the pitcher decided to stay with St. Louis.35

In the end, there was no injunction and Baumgardner signed a contract with the Browns paying him $3,000 for the season.36 That year, he turned in what was his best season with the Browns, going 16-14 with an ERA (2.79) that ranked in the top half of the league among hurlers with more than 150 innings pitched. Again, when the year ended, the Federal League set its sights on landing him and the Browns found themselves having to court the pitcher when he refused to sign his contract at first. The bone of contention was that Branch Rickey, who had taken over as manager after the team had fired Stovall, had several times mentioned that he would consider trading Baumgardner, who preferred to stay in St. Louis, and he insisted he would not sign unless the team promised it wouldn’t trade him.37 It may also have helped that his contract for 1915 gave him a substantial raise by the day’s standards, to $4,200.38 Perhaps more than his record of the season before, the increase in his salary came about because he had scored highly on an arcane “cardiac test” that Rickey had devised and which, according to Rickey, measured in a mathematical way a player’s competitiveness and coolness under pressure.39

As it turned out, Baumgardner’s performance over the next two years make plain that the test returned flawed results, at least in his case, as he pitched only 30⅓ innings in 1915 and 1916 combined.

He reportedly showed up in camp in 1915 in such bad shape that one sportswriter referred to him as a “class Z” pitcher and suggested he would not be ready to pitch in league competition until sometime in May.40 His condition was made worse when he was struck in the head by a line drive by Dee Walsh while pitching batting practice; he lay unconscious for half an hour.41 (In a gibe at Baumgardner, the writer added, “Had the blow landed on a vulnerable spot the result might have been very serious.”42)

Not surprisingly, then, Baumgardner got off to a miserable start. He made his first appearance on April 15, entering the game in the third with the Browns trailing the White Sox 9-0; he pitched the final seven innings, surrendering seven runs on 10 hits and three walks, though only four of the runs were earned. The next time out, on April 24, he pitched the final inning of a 4-1 loss. Because he surrendered only one hit and no runs, Rickey decided Baumgardner was ready to start; he did the next day, and he pitched well, allowing only one run on four hits; but the Browns were shut out and he took the loss. The press, however, looked on it optimistically:

“Though he lost … much praise is due George Baumgardner, the erratic speed ballist … for the wonderful pitching [he] exhibited Sunday. ‘Baumy’ hurled a beautiful game and deserved better luck. … [The] news of Baumgardner’s return to form will doubtless cheer [Rickey].”43

Rather than being the beginning of his return to the form the Browns expected of him, however, the game was the last time Baumgardner was effective on the mound. Over the next two weeks he pitched in four more games, all in relief, throwing a total of 6⅓ innings, allowing seven runs on 14 hits and six walks. With the Browns in last place, already 10½ games out of first place by May 10, Rickey decided to clean house and tried to send Baumgardner to the minor leagues. He refused and went home to West Virginia instead.44

There, Baumgardner latched on with a local semipro team and at least one report claimed he had gotten into shape and that his pitches seemed to have the same pop and movement; however, rather than taking any initiative to contact the Browns, Baumgardner waited for them to call. “I am waiting to hear from them. … I ain’t much at letter writing, they don’t need to expect any word from me.”45

Rickey offered Baumgardner a chance to come back to the Browns for 1916 but before spring training ended, the Browns gave him his release. He persuaded them to let him stay with the team by saying he would pay his own expenses as he tried to get into shape.46 The team finally gave him a contract calling for $75 a month and he became the focus of much derision after that, as Memphis in the Southern League offered him a contract calling for $200 a month, but he declined, saying, “Nobody would see me if I went to Memphis.”47 One article that mocked him for his lack of financial acumen added, “George Baumgardner … is all puffed up like a pouter pigeon because he has signed a new contract with the Browns. All of which only proves how easy it is to get Baumgardner all puffed up.”48

He appeared in only four games for the Browns in 1916, pitching eight innings, before the team released him for what would turn out to be the last time. He picked up with Little Rock of the Southern Association, which welcomed him enthusiastically: Describing him as a “graceful pitcher” who “works hard but doesn’t show it on the surface,” team President Robert G. Allen predicted that Baumgardner would “burn up this league.”49

However, it later came out that Baumgardner had reported to the team with a “strained and dislocated nerve in his back that [caused] him pain every time he [threw] the ball.”50 After only five games, he surrendered to the pain and went back to West Virginia “to get the old soup bone ready for next year.”51 There, he experimented briefly with trying to become a southpaw.52

Baumgardner returned to Little Rock for 1917 (as a right-handed pitcher) and threw a combined no-hitter with teammate Tom Phillips in the season opener but was bombed his next time out, surrendering 20 hits and eight runs, and then pitched inconsistently after that. After he appeared in 15 games, going 3-5 with a 5.14 ERA, the eighth-worst among pitchers with 70 innings or more, the team let him go, ending his professional career, though at least one newspaper story says that he played independent semipro baseball in West Virginia for a time.53

Baumgardner joined the US Army in early 1918, training at Camp Shelby in Mississippi. While he was there, he reportedly married a woman named Nellie Dietz, whom newspaper accounts of the marriage described as an “artist’s model.”54 They eventually divorced.55 He eventually ended up in France where, in 1919, he reportedly was a sergeant in the 150th Infantry.56

Two years later, Baumgardner signed a contract with Joplin of the Class-A Western League, but there are no records that he ever appeared in a game with them.57

At the time of the 1930 census, Baumgardner was living with a brother in Barboursville and working as a laborer in the building industry.58 The 1940 census also shows him living with his brother, but does not report an occupation; his World War II draft card, which he filed in 1942, also leaves blank the space for employment.59 Baumgardner died from a heart attack due to a coronary occlusion on December 13, 1970.60 His obituary in the Huntington Herald-Dispatch says he was an active member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and was survived by one of his sisters and several nieces and nephews.61

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consultedAncestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Pick Up Baumgardner,” Huntington (Indiana) Press, June 20, 1913: 6.

2 “Baumgardner Rube’s Successor; ‘High Nut’ of Baseball,” Akron Beacon Journal, January 11, 1915: 9.

3 Year: 1900; Census Place: Barboursville, Cabell, West Virginia; Roll: 1756; Page: 3B; Enumeration District: 0001; FHL microfilm: 1241756; Year: 1910; Census Place: Barboursville, Cabell, West Virginia; Roll: T624_1678; Page: 3B; Enumeration District: 0007; FHL microfilm: 1375691.

4 George W. Baumgardner player questionnaire on file in A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Cernter of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

5 “Allen Could Not Get Pitcher Baumgardner and Now George Signs to Play for Only $75,” Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock), June 9, 1916: 13.

6 George Baumgardner contracts for 1914 and 1915, Giamatti Research Center.

7 “Baumgardner Not Yet Old Enough to Cast His First Vote,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 5, 1912: 20.

8 “G. Baumgardner and Chapman Join Team,” Arkansas Democrat, July 27, 1916: 7.

9 “Baumgardner Rube’s Successor.”

10 Louis Lee Arms, “George Baumgardner, Brownies’ Mound Artist, Is Worthy Successor to Waddell and Raymond,” Washington Times, January 1, 1915: 10.

11 “Hard Hitters Are Wanted for Team,” Paducah (Kentucky) Sun Democrat, July 27, 1910: 4.

12 “Virginia Valley League,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 5, 1910: 13

13 “Virginia Valley League,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 15, 1910: 8.

14 “Leach’s Barnstormers Make It Four Straight,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, October 14, 1910: 9.

15 “Scout Who Discovered George Baumgardner Is Signed by Cleveland,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 22, 1912: 18.

16 “Another Hurler for Browns,” Indianapolis News, June 19, 1911: 10.

17 “New Battery for Browns,” Washington Post, July 7, 1911: 8.

18 “Pick Up Baumgardner.”

19 Ibid.

20 W.J. O’Connor, “Browns’ Advisory Board Discovers New ‘Wonder’ in Pitcher Baumgardner,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 23, 1912: 7.

21 Ibid.

22 Sam Weller, “Youngster Stars in Defeat of Sox,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1912: 13.

23 “Browns Tie White Sox in 15 Inning Game,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 21, 1912: 21.

24 “Sox and Browns in 15 Rounds Without Score, Washington Post, April 21, 1912: Sports-1.

25 “George Baumgardner of the St. Louis Browns Is the Pitching Sensation of the Current Baseball Season,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix), June 2, 1912: 10.

26 Grantland Rice, “Bingles and Bunts,” Washington Times, April 25, 1912: 15.

27 Clarence Lloyd, “Johnson Shares Pitching Honors With Joe Wood,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 13, 1912: 15.

28 “Baseball Aftermath,” Pittsburgh Press, November 11, 1912: 12.

29 “Cobb’s Vicious Slide Puts Out Browns Star Catcher,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 6, 1912: 7.

30 “Baumgardner Was Real Homesick,” Huntington Herald Dispatch, April 30, 1912: 2.

31 “Geo. Baumgardner, Bug, Has Keeper to Pilot Him in Larger Cities,” Lansing (Michigan) State Journal, September 17, 1912: 8.

32 “Heat Waves From Radiator League,” Wilkes-Barre Record, December 2, 1912: 9; “Short Snappy Sportlets,” El Paso Herald, January 22, 1913: 9; W.J. O’Connor, “Hedges May Balk Detroit’s Plan to Release High,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 31, 1913: 16.

33 “Baumgardner Has Signed,” Pittsburgh Press, January 13, 1913: 19.

34 Clarence F. Lloyd, “Baumgardner Is Loyal to Browns, Rickey Declares,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 26, 1913: 7; “Mystery of the Jumping Quintet Still Unsolved by Browns’ Owner, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 10, 1914: 6.

35 “Stovall’s Failure to Land Brownies Means Legal Fight,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 12, 1914: 19.

36 George W. Baumgardner 1914 Contract.

37 Harry F. Pierce, “Baumgardner Will Not Sign a Contract With Browns Until Team Reaches Camp at Houston,” St. Louis Star and Times, November 12, 1914: 14.

38 George W. Baumgardner 1915 Contract.

39 W.J. O’Connor, “Cardiac Test Applied to All Browns; Austin Fails,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 8. 1915: 14

40 Harry F. Pierce, “Brownies Are Not Enthusiastic Over Opening of Season,” St. Louis Star and Times, April 13, 1915: 11.

41 L.C. Davis, “Sport Salad,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 9, 1915: 16.

42 Ibid.

43 John M. Quinn, “Brilliant Return of Baumgardner Brings Promise,” St. Louis Star and Times, April 26, 1915: 10.

44 Harry F. Pierce, “Ordered to Report to Louisville Club, Baumy Balks,” St. Louis Star and Times, May 11, 1915: 13.45 Billy Evans, “Looking Them Over,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 7, 1916: 12.

46 “Baumgardner Pays His Way,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 9, 1916: 35.

47 “Baumgardner Not Best Businessman on Earth,” Twin City Daily Sentinel (Winston-Salem), June 21, 1916.

48 “All Could Not Get Pitcher Baumgardner.”

49 “George Baumgardner,” Daily Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), July 27, 1916: 8.

50 “Baumie Pitches Well, Jake Hits Homer, Rain Helps,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, August 2, 1916: 6.

51 “Baumgardner Going Home to Plan 1917 Coup,” Arkansas Democrat, August 21, 1916: 7.

52 “George Baumgardner Is Now a Left-Hander, St. Louis Star and Times, March 21, 1917: 13.

53 “Baumgardner Is Out,” El Paso Herald, October 6, 1917: 14.

54 “Cannon Balls, Wedding Bells for Baumgardner,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, February 18, 1918:6.

55 George W. Baumgardner Certificate of Death, on file with the A. Barlett Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

56 “An Old Friend,” Arkansas Democrat, March 27, 1919: 11.

57 “Baseball Notes,” Galena (Kansas) Evening Times, May 14, 1921: 3.

58 Year: 1930; Census Place: Barboursville, Cabell, West Virginia; Roll: 2528; Page: 9B; Enumeration District: 0001; Image: 427.0; FHL microfilm: 2342262

59 Year: 1940; Census Place: Barboursville, Cabell, West Virginia; Roll: T627_4397; Page: 14B; Enumeration District: 6-1; The National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; Draft Registration Cards for Fourth Registration for West Virginia, 04/27/1942 – 04/27/1942; NAI Number: 563733; Record Group Title: Records of the Selective Service System; Record Group Number: 147

60 George W. Baumgardner Certificate of Death

61 “George Washington Baumgardner,” Huntington Herald-Dispatch, December 14, 1970: 6.

This biography is included in 20-Game Losers (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin, Emmet R. Nowlin. To get your free e-book copy or 50% off the paperback edition, click here.

Full Name

George Washington Baumgardner

Born

July 22, 1891 at Barboursville, WV (USA)

Died

December 13, 1970 at Barboursville, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.