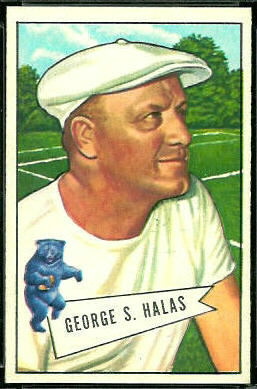

George Halas

On September 17, 1920, a group representing 11 different professional football teams congregated in Ralph Hay’s automotive showroom in Canton, Ohio, to discuss the formation of the very first professional football league. Among those who were present was a young man who was representing a professional football team from Decatur, Illinois. “That meeting in Hay’s showroom must have been the most informal on record,” the young man later said. “There were no chairs. We lounged around on fenders and running boards and talked things over.”1 When the meeting concluded, the American Professional Football Association (APFA) had been formed. Two years later, the name would be changed to the National Football League.

On September 17, 1920, a group representing 11 different professional football teams congregated in Ralph Hay’s automotive showroom in Canton, Ohio, to discuss the formation of the very first professional football league. Among those who were present was a young man who was representing a professional football team from Decatur, Illinois. “That meeting in Hay’s showroom must have been the most informal on record,” the young man later said. “There were no chairs. We lounged around on fenders and running boards and talked things over.”1 When the meeting concluded, the American Professional Football Association (APFA) had been formed. Two years later, the name would be changed to the National Football League.

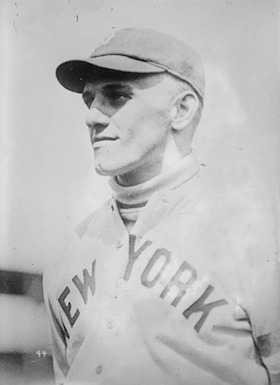

Just a little over a year before that meeting at Hay’s showroom, Halas was a highly rated prospect going into his 1919 rookie season with the New York Yankees. “There is a young man on the New York roster that is being overlooked and will make New York sit up and take notice next summer. That young man is George Halas,” wrote a sportswriter in the Chicago Tribune.2 But Halas’s major-league debut was delayed when he injured a hip during a spring-training game. Hampered by his injury, he made just two hits in 22 trips to the plate once the season began. In July, with permission from the Yankees, Halas traveled to Youngstown, Ohio, to visit a sports injury specialist named John D. “Bonesetter” Reese. Reese was able to immediately fix Halas’s hip problem, but when Halas rejoined the Yanks in Cleveland, “(I)t was too late. A fellow named Babe Ruth was playing in my place.”3

George Stanley Halas was born on February 2, 1895, in the fast-growing city of Chicago. He was the fourth child of Frank and Barbara Halas to survive infancy. Frank and Barbara were hard-working Bohemian immigrants who taught their children the value of a strong work ethic and to appreciate their opportunity to build a good life in the land of opportunity. “I was blessed the day I came to America,” Barbara would tell her children. She also stressed that the best way to advance was to be an American in every way.4

Frank Halas was a reporter for a Bohemian-language newspaper before becoming a tailor and shop owner. He sold his business after suffering a stroke and invested his proceeds from the sale into a three-story structure that consisted of two apartments and a grocery store. He was too frail to work (he died in 1910), and to help stave off poverty, the rest of the family pitched in. “Every day after school, my brothers and I performed the janitor’s chores for those apartments,” said Halas. His job was to shovel coal, shovel snow, and clean the furnaces. His mother ran the grocery store and “our sister Lillian helped mom at the store.” George also got up at 5:30 every morning to run a paper route before school. He attended church, and he found time for sports.5

In 1909 Halas entered Crane Tech high school, which offered courses in carpentry and foundry work, but also had college-preparatory classes, which Halas enrolled in. He also played on the school sports teams. Although small for his age (he weighed 110 pounds during his freshman year), he played on Crane Tech’s football, basketball, and indoor baseball (softball) teams.

During his sophomore season, Halas was pitching one day for the indoor baseball team against rival Harrison Tech high school. While on the mound, Halas heard a female student shout from the seats from the opposition’s side: “Ham and Eggs, Ham and Eggs, Ham can’t catch and Eggs can’t pitch.”6

“Jack Hamm was our catcher, so I must have been Eggs,” Halas would later say. “I had to admit that she was pretty. And she was certainly spirited. I made it my business to find out who she was.” She was Wilhelmina “Min” Bushing, who lived just three blocks away. Through a friend who attended Harrison Tech, Halas was able to meet Ms. Bushing, and got to know her by inviting her to ice-cream parties. Soon they were dating, although there was an obstacle: Min’s family was German Lutheran; Halas’s background was Bohemian Catholic. But that did not stop them, “nor did our families speak up against one another,” said Halas .7

“I got a good education at Crane Tech,” Halas said. He was ready for college after his high-school graduation, and hoped to follow his brother’s footsteps by enrolling at the University of Illinois. His brother advised him to wait a year. During the year off he worked in the payroll department at Western Electric, which was where Min also worked. “I made it a point to pass by Min’s desk every morning to say a few words,” said Halas.8 In addition, he played semipro baseball

In the fall of 1914 Halas enrolled at the University of Illinois, where he studied to become an engineer. And since he had gained weight, filled out, and was no longer considered small for his age, Halas played three sports for the Fighting Illini – football, basketball, and baseball – and excelled in all three. He played end on the football team, was said to be a good shooter in basketball, and starred on the baseball team, where he was known for his hitting, his speed on the basepaths, and his ability to cover ground in the outfield. He hit .350 during his sophomore season. In his junior year Halas caught the eye of New York Yankees scout Bob Connery, who invited him to join the Yankees at spring training. Halas declined the invite since he was more interested in earning his degree, but did say he would be interested after college. Then his college education and any professional baseball career were delayed with the United States’ entry into World War I.

Halas wanted to enter the war effort, hoping to be sent to sea on a submarine chaser, which did not make his mother happy; she wanted her son to finish his college education. But the Navy had other ideas, and stationed Halas at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, outside Chicago, where he was placed in the station’s athletic program. In 1918 the Great Lakes football team, with Halas playing end, was invited to play in the Rose Bowl on January 1, 1919, against the Mare Island Marines (from Vallejo, California). Halas caught a touchdown pass and intercepted a pass to set up another touchdown in a 17-0 Great Lakes win.

Discharged from the Navy after the war, Halas signed with the Yankees for a salary of $400 per month and a $500 signing bonus. His college education was now completed, the University of Illinois having awarded him his diploma for his service in the war. In the spring of 1919, Halas reported to the Yankees for spring training in Jacksonville, Florida, and made an immediate impression.

“It is unusual for a college player to jump into the big leagues and become a regular the first season, but this is just the thing that Halas threatens to do,” wrote a New York Times sportswriter. “He is swift afoot and is a heady and proficient base runner. He covers a lot of ground in the outfield, and best of all he is a world of enthusiasm for the game.”9

While playing in a spring-training game against the Brooklyn Dodgers, Halas batted against future Hall of Fame hurler Rube Marquard. “I knew Rube had a dandy curveball, but I figured he wouldn’t risk an arm injury by throwing a curve against a rookie in the spring. So I dug in looking for a fastball,” Halas would later say.10

Halas drove a fast one deep into center field for a hit. As he approached second base, he saw that the ball was still rolling. He rounded second and headed to third. Before approaching third base, he hit the brick-hard clay and made a long hook slide for a triple. “That slide was the beginning of the end of my baseball career,” Halas said. The jolt of hitting the hard dirt in his slide had jarred his hip. The injury would hamper him for the first few months of the season.11

Halas had been expected to start the season in the Yankees outfield. However, the hip injury slowed his progress and he did not make his first appearance of the season until May 6, at Philadelphia, when Miller Huggins inserted him into the leadoff spot, and in right field. In that game, he got his first major-league hit, off A’s pitcher Scott Perry, and made one catch in the outfield. Two days later in Philadelphia, Halas was back in the starting lineup, and once again leading off while playing right field. The Yankees won, 2-0, on a one-hit shutout by Bob Shawkey. Halas once again went 1-for-4, with a single off A’s pitcher Bob Geary. The single was the second and final hit of Halas’s major-league career.

Three days later, in New York, Halas was in the starting lineup against Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators. Halas went 0-for-5 and struck out twice, but almost hit one out against the great pitcher. He hit Johnson’s first pitch, a fastball, deep to right field, but the drive curved foul. He hit the next pitch, another fastball, and sent another long drive into the right-field bleachers, but once again the ball was foul. He then swung at Johnson’s next offering, a curveball, and missed for strike three.

When the Yankees played Detroit, Halas, not in the lineup, received an assignment from a few of the New York veterans: to egg on Ty Cobb. When Cobb came to bat, Halas began to shout to the point where he got the Tigers star to react. Cobb dropped his bat and pointed as he paced toward the Yankees dugout. “Punk. I’ll see you after the game! Don’t forget that, Punk.”

Halas showered after the game, then dressed and left the locker room. As promised, Cobb was waiting for him, but instead of evening the score, Cobb extended his hand and said, “I like your spirit, kid, but don’t overdo it when you don’t have to,” then he turned and walked away.

By the time Halas visited Bonesetter Reese in July, he was hitting just .091 in 12 games. When he arrived in Cleveland to rejoin the Yankees after Reese had fixed his hip, manager Miller Huggins gave him the news that he was being sent to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association. The reason wasn’t what Halas said for the rest of his life – that Babe Ruth was now New York’s starting right fielder; Ruth didn’t join the team until the next year. It was that the minor leagues would offer him a chance to improve his game. “I was devastated,” Halas would later say. “But looking back on it I was grateful for the manner in which Miller Huggins told me. Through the years, whenever I had to cut a player, I have tried to emulate Huggins’ grace and consideration.”12

As a part-time outfielder for the Saints, Halas was batting .274 late in the season. Saints manager Mike Kelley decided to convert Halas into a second baseman. The 1920 Saints were closing in on the American Association pennant when Halas elected to return to Chicago to work for the Chicago, Burlington, & Quincy Railroad for a salary of $55 a week. He also played for a semipro football team in Hammond, Indiana, for $100 a week.13 Twice a week, Halas would travel to Hammond, for practice on Thursday and a game on Sunday. But his future still appeared to be in baseball. Mike Kelley expected Halas to be his starting second baseman in 1920. Halas was willing to play in St. Paul for another season, but on one condition: that the Saints pay him the same salary the Yankees had in 1919. Kelley was willing, but with the condition that the Yankees release him to the Saints. Fearing that that would risk the possibility of another team purchasing him, the New Yorkers refused to release Halas. Unwilling to play for less, Halas decided on a career change.

In the spring of 1920, Halas received an offer from the A.E. Staley Company in Decatur, Illinois. Staley, a sports enthusiast who owned a corn-products manufacturing, wanted to build the best semipro football team in the land. He liked Halas; the fact that he played college and semipro football and had a degree in engineering made him ideal to oversee the day-to-day operations of his manufacturing plant, as well as organize and coach his football team. “Bring the best players around,” Staley told Halas. “I’ll give them jobs – they’ll earn a living here and play football for us.”14

Halas’s recruits for Staley’s football team before the 1920 season included a back from the University of Illinois named Dutch Sternaman, who would help Halas in recruiting and directing the team.

Halas’s recruits for Staley’s football team before the 1920 season included a back from the University of Illinois named Dutch Sternaman, who would help Halas in recruiting and directing the team.

While recruiting, Halas heard rumors about a professional football league being formed, which intrigued him. He confirmed the rumors to be true when he contacted Ralph Hay, the Canton auto dealer, who owned the Canton Bulldogs, to schedule a game between the Staleys and the Bulldogs. Then, on September 17, 1920, the two men met in Hay’s automobile showroom with other interested parties who represented nine other professional teams to plan for the organization of the American Professional Football Association.

The APFA began play in October of 1920. No records or statistics were kept. The majority of games were against semipro teams. Five of the Staleys’ 12 games were against semipro teams. They played five games against other professional teams, and won 10 and tied one of their 12 total games.

In 1920 America was locked in the jaws of a recession, and Decatur, Illinois, was not excluded from the tough times. Staley could no longer fund his football team. “I know you’re more interested in football than business,” Staley told Halas, “but we simply can’t underwrite the team’s expenses any longer. Why don’t you move the boys up to Chicago? I think pro football can go over well up there – and I’ll give you $5,000 to help you get started. All I ask is that you continue to call the team the Staleys for one more season.”15

And so Halas and Sternaman transferred their team to Chicago without a place to play their home games in the 1921 season. Halas approached Chicago Cubs team president William Veeck Sr. about the cost for the Staleys to rent Wrigley Field. “Fifteen percent of the gate receipts,” replied Veeck, “and we keep all the profits from concessions.”16 That sounded good to Halas. The next job was to promote his team. He and Sternaman handed out leaflets around town to advertise the Staleys’ coming games, and they took out small ads in the local newspapers. In their first season in Chicago, the Staleys averaged fewer than 10,000 spectators per game and finished the season with a 10-1-1 record to win the first league championship.

In 1922 Halas married his sweetheart, Min Bushing. They would have two children, Virginia, born in 1923, and George Jr., also known as “Mugs,” born in 1925. Also in 1922, the American Professional Football Association changed its name to the National Football League and the Staleys’ nickname was changed. Believing that associating with the Cubs would help the team gain recognition, Halas renamed his team the Chicago Bears.

In 1923 the NFL was still attempting to burst into the sports spotlight. Most people were unaware that professional football existed. Several teams were struggling to stay in business, including the Bears, who were said to be lucky to fill 12,000 seats per home game in the 35,000-seat Cubs Park. One of the highlights of the 1923 season occurred on the rainy day of November 4, when the Bears’ right end, 6-foot, 182-pound George Halas, returned a Jim Thorpe fumble 98 yards for a touchdown for an NFL record that would stand for 49 seasons.

Two years later, in 1925, the NFL was still trying to gain recognition. Realizing the league would need a player as popular as Babe Ruth to attract big crowds and receive publicity, Halas and Sternaman knew one existed at their alma mater, the University of Illinois, in the person of All-American tailback Red Grange. During the summer of 1925, they sent letters to Grange, but they went unanswered. Then one day a man named Charles “Cash and Carry” Pyle paid a visit to Halas and Sternaman and introduced himself as Grange’s agent. He confirmed that Grange was interested in playing professional football.

Immediately after Grange played his last football game for Illinois, on November 21, he signed with the Bears for $2,000 per game. Pyle and Grange also formed a company that would receive two-thirds of the profits from two tours the Bears had scheduled, one in December of 1925 (to St. Louis, Philadelphia, New York, Washington, D.C., Pittsburgh, Detroit, and one final game in Chicago) and one from coast to coast in January of 1926 (with games in Florida, New Orleans, California, Portland, and Seattle).17

When Grange joined the Bears, the NFL became a huge attraction. Sports fans everywhere wanted to see him play. The Bears now played before capacity crowds. But problems surfaced. Pyle demanded that Halas and Sternaman surrender one-third of the Bears ownership to the Pyle-Grange Company. The two team owners refused, and Grange and Pyle left the Bears and formed a new league – the American Football League – with Grange owning and playing for the New York Yankees, while Pyle owned all of the other teams in the league. The league folded after a season, although Grange’s Yankees joined the NFL for the 1927 season. After an injury sidelined him for the entire 1928 season, Grange returned to the Bears in 1929 and finished out his career with Chicago, retiring after the 1934 season.

By 1929 Halas and Sternaman began to have their own differences on how the team should operate. They did agree that the Bears needed a new head coach, and they also managed to agree on who the coach should be: Ralph Jones, an assistant football coach and the head basketball coach at Illinois when Halas was there. Jones was coaching Lake Forest College’s football team in a Chicago suburb when Halas and Sternaman hired him to coach the Bears, starting in 1930.

Jones was a maverick: His teams did not run the standard offense of the day, the single wing (or the more complex Notre Dame Box). Instead he ran a T-formation, with the quarterback lined up over the center to take the snap rather than having the center make a long snap to one of the running backs, and with the three other backs lined up horizontally behind the quarterback instead of one back being used as a wingback.

As Jones took over, Halas retired as a player to focus on the team’s day-to-day operations. In 1932 Jones coached the Bears to their second NFL championship. However, with times tough during the Depression, and with the Bears struggling to break even during these tough times, Halas decided the team could no longer afford to pay a head coach. He decided to return to coaching, much to the dismay of Sternaman. The two agreed that it was time for them to go their separate ways. The question was who would leave and who would own the Bears? Halas always seemed to be the person most involved in the team’s operations. Sternaman had other businesses, including real estate, and agreed to sell his shares for $38,000, to be paid in installments over the next few years. Finding financial backers during the 1930s wasn’t easy, but Halas found them in his mother, a few of his players, and future NFL team owner Charles W. Bidwell.18

Despite the Depression, the NFL continued to progress. In 1933 the league was split into two divisions, with the first-place teams in each playing each other for the league championship. In the championship game that season, the Bears beat the New York Giants, 23-21, for Halas’s second championship as a head coach. In 1934 the Bears rolled up 13 straight wins for an undefeated season, but lost to the Giants in the championship game.

In 1936 for the first time, all teams played the same number of games in a season. Also that year, the NFL held its first college player draft.

In 1937 Halas’s Bears made it back to the championship game, but lost to the Washington Redskins. That loss was a bitter pill for Halas to swallow, for his team had a better record and had expected to win, but was carved up by the accurate passing of Redskins quarterback Sammy Baugh. Halas learned something in defeat: the importance of having a good passing game. Wanting his team to have a strong passing attack, he modified the T-formation offense he had learned from Jones by changing the blocking assignments and including more passing plays. All he needed was a quarterback who could pass and had the intelligence to run the renovated T-formation. He believed the person right for the job was Columbia University tailback Sid Luckman, who was one of the best college players in the country in the late 1930s. But there was one obstacle to obtaining the All-American back: The Bears had finished the 1939 season with a 6-5 record, meaning that Luckman would be taken in the draft by the time the Bears were on the board to make their first-round selection. In one of the most lopsided trades in sports history, Halas sent end Edgar “Eggs” Manske to Pittsburgh for the Steelers’ first-round draft choice, which the Bears used to take Luckman.

With Luckman as quarterback, the Bears won four consecutive Western Conference championships (1940-1943) to earn the nickname Monsters of the Midway. In the 1940 championship game they annihilated the Washington Redskins, 73-0. They also won the 1941 and 1943 championship games. In 1942 the Bears went undefeated through the season, winning all 11 games, but as in their undefeated 1934 season, they lost the championship game, to the Redskins.

With the outbreak of World War II, Halas received a Navy commission after the 1942 season and helped supervise recreational activities for the 7th Fleet in the Pacific. In 1943, under interim co-coaches Hunk Anderson and Luke Johnsos, the Bears went 8-1-1 and defeated the Redskins for the league championship. In 1944, again under Anderson and Johnsos, but with several key players serving in the military, the Bears fell to 6-3-1, and then in 1945, the once proud Bears lost seven of their first eight games. By Thanksgiving, with the war over, Halas was out of the Navy. (His formal discharge came in 1946.) He returned to his familiar spot on the Bears sidelines and guided the team to two wins to close out what was a disappointing season. Halas vowed that the Bears would be back in 1946. He was right; the Bears went 8-2-1 and defeated the Giants for the championship.

The 1950s were a time for change – for the NFL and for the Halases. Television had now brought pro football into American homes. There were NFL teams from coast to coast. George and Min were now grandparents. Their daughter, Virginia, was married and the mother of 11 children; Mugs was working in the Bears organization. After graduating from Loyola University in Chicago, Mugs joined the Bears front office in 1950 and became the team’s treasurer in 1953. He would later become team president. To honor a promise he had made to his wife, George Sr., who turned 60 in 1955, stepped down as the coach. He now handled the team’s day-to day operations and focused on his grandchildren, while Paddy Driscoll coached the team. But Halas could not stay away for long, and in 1958 he replaced Driscoll as head coach.

By the 1960s Halas had scrapped his T-formation offense for a pro-set offense on two running backs, a tight end, a wide receiver, and a flanker. In 1963 the Bears finished with an 11-1-2 record to win the Western Conference championship, and then defeated the New York Giants in the championship game, 14-10, Halas’s last championship as a head coach.

In 1965 Halas, now 70, coached a strong team that won seven of its last 10 games for a 9-5 season, but tragedy struck after the season when Min Halas died unexpectedly. Halas was heartbroken but remained as the Bears head coach for two more seasons, deciding to retire after the 1967 season with 318 career wins and six NFL championships.

After retirement Halas remained active in the Bears front office until before the 1974 season, when Mugs Halas, realizing that changes were needed because the Bears had not had a winning season since 1967, convinced his father that it was in the best interests of the team for him to surrender his power to somebody else. George Halas was reluctant but listened, and Jim Finks, the architect of the powerful Minnesota Vikings teams of the late 1960s and early 1970s, was hired as general manager. The team gradually improved under Finks’ direction, and in 1977 the Bears made the playoffs for the first time since 1963. In 1979, on the morning of the final game of the season, tragedy struck when Mugs Halas died of a massive heart attack. Devastated by the loss of his son, George Halas remained out of the public eye for several months. When he regained his strength, he became more active in the Bears organization. Always opposed to the hiring of Finks, he reduced the general manager’s power and relied more on Jerry Vainisi, the Bears’ treasurer. Halas continued to reduce Finks’ duties until Finks resigned in August 1983 and Halas promoted Vainisi to replace him.19

In 1982 Halas hired former Chicago Bears great Mike Ditka as head coach. In 1983 Halas was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He died on October 31, 1983, at the age of 88. Shortly before his death he gave Ditka a bottle of Dom Perignon champagne, and told him, “Mike, don’t open it until you win the Super Bowl.”20

On January 26, 1986, under the direction of Mike Ditka, the Bears won the Super Bowl, 46-10 over the New England Patriots. And Ditka opened the bottle of champagne and drank it.

Notes

1 Richard Whittingham, The Chicago Bears: An Illustrated History (Chicago, New York, San Francisco: Rand McNally & Company, 1979), 18.

2 Chicago Tribune, February 4, 1919.

3 George Vass, George Halas and the Chicago Bears (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1971), 20.

4 George Halas, Halas by Halas: The Autobiography of George Halas (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979), 16.

5 Vass, 15.

6 Halas,.25.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid., 28.

9 New York Times, April 13, 1919.

10 Vass, 6.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid., 48.

13 Vass, 22.

14 Whittingham, 17.

15 Ibid., 21.

16 Ibid., 21-22.

17 Ibid., 42-43.

18 Ibid., 84.

19 Armen Keteyian, Ditka: Monster of the Midway. (New York: Atria, 1992), 157-158.

20 Steve Delsohn, Da Bears! How the 1985 Monsters of the Midway Became the Greatest Team in NFL History (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2010), 107.

Full Name

George Stanley Halas

Born

February 2, 1895 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

October 31, 1983 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.