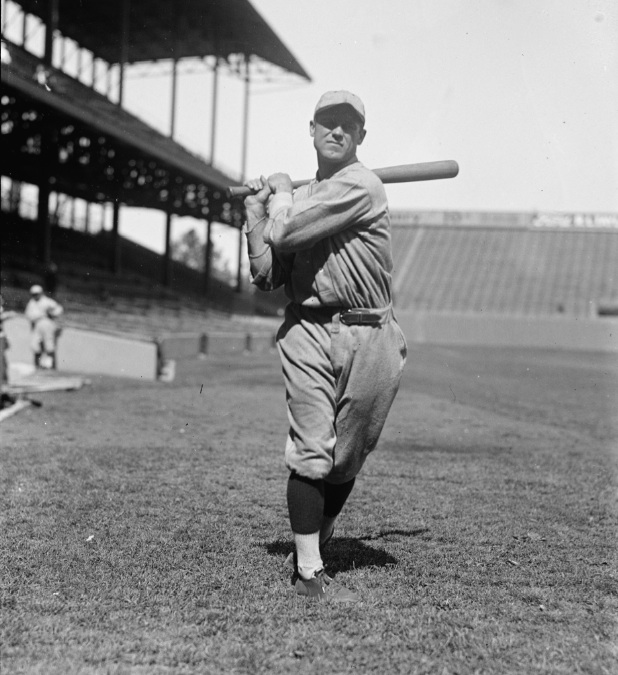

George Sisler

Arguably the first great first baseman of the twentieth century, George Sisler was the greatest player in St. Louis Browns history. An excellent baserunner and superb fielder who was once tried out at second and third base even though he threw left-handed, Sisler’s primary asset was his left-handed swing, which he used to notch a career .340 batting average. From 1916 to 1925, Sisler batted over .300 nine consecutive times, including two seasons in which he batted better than .400, making him one of only two players in American League history (the other was Ty Cobb) to post multiple .400 batting marks. Though Sisler’s greatest feats occurred in the years immediately following the end of the Deadball Era, by 1919 he had already established himself as one of the game’s top young stars, placing in the top three in batting average every year from 1917 to 1919, and leading the league with 45 stolen bases in 1918. That year one writer declared that Sisler possessed “dazzling ability of the Cobbesque type. He is just as fast, showy, and sensational, very nearly if not quite as good as a natural hitter, as fast in speed of foot, an even better fielder, and gifted with a versatility Cobb himself might envy.”

Arguably the first great first baseman of the twentieth century, George Sisler was the greatest player in St. Louis Browns history. An excellent baserunner and superb fielder who was once tried out at second and third base even though he threw left-handed, Sisler’s primary asset was his left-handed swing, which he used to notch a career .340 batting average. From 1916 to 1925, Sisler batted over .300 nine consecutive times, including two seasons in which he batted better than .400, making him one of only two players in American League history (the other was Ty Cobb) to post multiple .400 batting marks. Though Sisler’s greatest feats occurred in the years immediately following the end of the Deadball Era, by 1919 he had already established himself as one of the game’s top young stars, placing in the top three in batting average every year from 1917 to 1919, and leading the league with 45 stolen bases in 1918. That year one writer declared that Sisler possessed “dazzling ability of the Cobbesque type. He is just as fast, showy, and sensational, very nearly if not quite as good as a natural hitter, as fast in speed of foot, an even better fielder, and gifted with a versatility Cobb himself might envy.”

George Harold Sisler was born on March 24, 1893, the youngest of three children of Mary Whipple and Cassius Clay Sisler in Manchester, Ohio, 45 miles south of Cleveland. Like many rural communities of the day, baseball was a passion that united the town. Sisler’s extended family owned and populated much of the surrounding countryside, and young George quickly gained a reputation as a sterling ballplayer without sacrificing the educational values stressed by his parents, both graduates of nearby Hiram College.

While Sisler excelled on the athletic fields and in the classroom, his life turned as he entered his teenage years. Manchester had no high school, and at age 14 he moved to Akron, Ohio, to live with his brother Bert and advance his education. At Akron High, Sisler played football as a slender end, basketball as a smooth forward, and baseball as a southpaw pitcher noted for his speed and curve ball. Sisler also played on several pickup and semi-pro squads, and the local newspapers soon referred to the handsome boy as “Gorgeous George.”

Upon graduating from high school, Sisler followed the wishes of his parents and curbed plans to enter the professional ranks in order to pursue a college education. Rejecting scholarship offers from Penn and Western Reserve, Sisler decided to follow his high school catcher Russ Baer to Michigan. Sisler departed Akron with his sights set on law school, but upon his arrival in Ann Arbor enrolled in the engineering program due to his affinity for math.

With no firm plans to play collegiate baseball, Sisler didn’t act on the notion until several months after he arrived on campus. By that time, the Wolverines had filled their vacant coaching position with the man who would significantly impact Sisler’s life, Michigan law school grad Branch Rickey. In the late winter of 1912, the confident freshman reported for baseball tryouts at Waterman Gym. Although the session was only for upperclassmen, Rickey was persuaded by a team member to give the green freshman a chance, and by the end of the session Sisler was regarded as a top performer. Freshmen were not eligible for varsity competition, but by leading the first-year engineering students to the school baseball title over a strong group of junior law students, Sisler made his mark on campus.

Sisler’s career continued to gather momentum as he pitched in Akron’s industrial league that summer. He and his older brother Cassius, a catcher, comprised the core of the Babcock and Wilcox Boilerworks company team, and the local press chronicled his strikeout total and mound success. On one memorable Sunday afternoon, with the immortal Cy Young perched behind the plate as umpire, Sisler twirled a no-hitter against the Amherst Grays.

A full-fledged member of the Wolverine varsity nine during his sophomore year, Sisler’s fast start on the mound was interrupted by arm trouble, but his batting averaged remained around .500 most of the campaign. Rickey left the squad to join the Browns front office after the season, but Michigan finished 22-4-1, and Sisler’s .445 batting average and pitching success earned him All-America honors. Still plagued by a sore arm, Sisler starred at the plate for Akron’s B&W team again in the summer of 1913 before turning to famed sports medical professional John “Bonesetter” Reese for treatment. Despite a sore arm, the following season Sisler split time between the mound and the outfield, and finished the year with a .451 average. Once again, he was named to the All-America team.

At some point during the summer of 1910, before his senior year in high school, Sisler had signed a contract to play for the Akron Champs of the Ohio & Pennsylvania League. Sisler received no bonus money and never reported to the club, and Lee Fohl‘s Champs eventually sold the contract to Columbus. Acting on a tip from Cubs infielder Solly Hofman, Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss scouted Sisler in a sandlot game in Akron in the summer of 1912, purchased his contract, and insisted that Sisler report to the National League club. The story leaked to the press, and Sisler’s contract became public knowledge.

Confronted with the problem, Rickey’s keen mind soon found the loophole. Because Sisler was 17 when he signed, the contract was void without his father’s signature, and Rickey recognized that immediately. Rickey took the case to the National Commission, and after a protracted battle, Cincinnati owner Garry Herrmann cast the deciding vote on January 9, 1915, granting Sisler free agency upon entering the professional ranks.

Sisler then turned his eyes toward professional baseball, and toward his former mentor, the man he called “Coach” for the rest of his life, Branch Rickey. After entertaining an offer from Pittsburgh, Sisler signed with the St. Louis Browns for $300 a month, less than Dreyfuss offered him, though the Browns also paid Sisler a $5,000 bonus. Dreyfuss filed a complaint with the National Commission. At 22 years old, Sisler joined the Browns as a left-handed twirler in 1915. The rookie pitched 15 games that summer for the Browns, starting eight and throwing six complete games. In 70 innings he compiled a 2.83 ERA. While Sisler experienced mound success that summer, it took Rickey only a few days to start working him at first base and the outfield. His hitting came in spurts, but he ended the season with a solid .285 batting average, three homers and 29 RBI. The highlight of his rookie season was a 2-1 win over Walter Johnson on August 29 in which he limited the Senators to six hits and struck out three, winning the game thanks to Del Pratt‘s successful execution of the hidden ball trick. For the remainder of his life, Sisler spoke of that game as his greatest thrill in baseball. “Sisler can be counted a baseball freak,” the Washington Post reported the next day. “[Rickey] plays him in the outfield and he makes sensational catches… he plays him on first base and actually he looks like Hal Chase when Hal was king of the first sackers, and then on the hill he goes out and beats Johnson.”

St. Louis’ new controlling partner Phil Ball replaced Rickey with Fielder Jones during the 1916 season, but despite the changes Sisler consolidated his hitting gains and took over as the club’s first baseman. He hit .305, the first of nine straight seasons over .300, and rapped out 11 triples and four homers, as the Browns finished in fifth place with their first winning record in eight years. On June 10, 1916, the National Commission finally issued its ruling on Dreyfuss’s grievance, turning it down and declaring Sisler’s contract with St. Louis legitimate.

As war loomed on the national horizon in 1917 the newlywed Sisler, who had married his college sweetheart Kathleen Holznagle the previous fall, became a star. Limited to three mound appearances in 1916, none in 1917, and just two in 1918, Sisler’s grace around first base drew him accolades as one of the league’s top defensive players. He was also an offensive star, finishing second in the league in hits, fourth in doubles and fifth in stolen bases in 1917, and third in hits in 1918 with a league-leading 45 steals. The national press took to calling him “the next Cobb.”

From 1919 to 1922, Sisler largely fulfilled that promise, as he batted .407 to win his first batting title in 1920, collecting 257 hits, a major league record that would last 84 years. He captured his second batting crown in 1922 with a .420 mark, which still stands as the third-best season average in modern baseball history. After the 1922 season, Sisler was given the inaugural American League Trophy as the league’s MVP, voted on by a league-appointed panel of sportswriters.

Sisler finished second in the league in stolen bases in 1919 and 1920, and led the league in 1921 and 1922. Though Sisler often ranked among the league leaders in doubles, triples, and home runs, he was primarily a place hitter, adept at finding the gaps in opposing defenses. Like Cobb, Sisler stood erect at the plate, and relied on his superior hand-eye reflexes to react to a pitch’s location and lash out base hits. “Except when I cut loose at the ball, I always try to place my hits,” he once explained. “At the plate you must stand in such a way that you can hit to either right or left field with equal ease.” Unlike Cobb, who shifted his feet while hitting, Sisler was an advocate of the flat-footed swing.

At the peak of his powers following his historic 1922 performance, Sisler missed the entire 1923 season with a severe sinus infection that impaired his optic nerve, plaguing him with chronic headaches and double vision. Though he was able to return to the field in 1924, when he also agreed to serve as manager of the Browns, Sisler was never again the same player. He batted .305 in 1924–below the league average–improved to .345 the following year, but then batted just .290 in 1926 with a .398 slugging percentage. Under his management, the Browns finished fourth in 1924 and third a year later. After falling to seventh place in 1926, Sisler was removed as manager, and later admitted that he “wasn’t ready” for the post. In 1927, his last season with the Browns, he hit .327 and knocked out 201 hits. He was shipped to Washington before the 1928 season, but was traded to the Boston Braves early in the campaign. He finished his major league career in strong fashion, hitting .326 in 1929 and .309 in ’30.

After spending the 1931 campaign with Rochester of the International League and 1932 with Shreveport-Tyler of the Texas League, Sisler retired from baseball. He launched several private ventures, including a sporting goods company, and founded the American Softball Association. Sisler engineered the first lighted softball park, and that sport boomed throughout the 1930s. In 1939, Sisler was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the writers’ panel, and was among the first four classes of inductees enshrined that summer.

In 1942, Branch Rickey hired the 49-year-old Sisler to scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Sisler served in this capacity throughout the decade, but his greatest contribution may have come in preparing Jackie Robinson to break baseball’s color barrier. He scouted Robinson prior to his signing with the Dodgers, and helped the future Hall of Famer make the transition to first base during his first year in the majors. Sisler moved to Brooklyn to assume an expanded role with the Dodgers in 1947, and in addition to scouting and player development helped tutor several of the players that would serve as the foundation of the outstanding Dodgers teams of the 1950s. When Rickey moved to the Pirates before the 1951 season, Sisler again went with him. There he helped bring Bill Mazeroski into the fold, and also worked with Roberto Clemente, teaching him to keep his head still during his swing.

Sisler remained with the Pirates after Rickey left, but after serious abdominal surgery in 1957 he and Kathleen moved back to St. Louis. Despite the move, Sisler remained with the Pirates as a roving hitting coach, and instructed such players as Willie Stargell, Gene Alley, and Donn Clendenon. Sisler passed away on March 26, 1973, in Richmond Heights, Missouri. Kathleen survived him by 17 years. The couple had three sons, one of whom, Dick Sisler, spent eight years in the major leagues and later managed the Cincinnati Reds. Another son, Dave Sisler, had a seven-year career as a big league pitcher. George Sisler is buried at the Old Meeting House Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Frontenac, Missouri.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

George Harold Sisler

Born

March 24, 1893 at Manchester, OH (USA)

Died

March 26, 1973 at Richmond Heights, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.