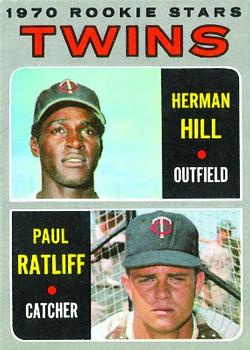

Herman Hill

Sometimes, even a short career and a short life can affect other people for a long time.

Herman Hill played in only 43 major-league games and was just 25 when he died in an accidental drowning. But almost a half-century after his death, the memory of him remained strong in the hearts of his family. And his name continued to convey prestige at the New Jersey high school where he graduated. For a time, his name also was associated with an important section of Major League Baseball’s early collective bargaining agreements.

Hill was a fleet, left-handed-hitting outfielder who played parts of 1969 and 1970 for the Minnesota Twins, often used as a pinch-runner. He drowned on December 14, 1970, in Venezuela during the 1970-71 winter league season. It was untimely end to a life that was, at times, like a classic American story of hardships overcome and dreams fulfilled.

Herman Alexander Hill was born October 12, 1945, in Tuskegee, Alabama, to Charlie and Milobelia Hill. His parents were sharecroppers, and he was one of 15 siblings—10 boys and five girls. Sharecropping was a tough existence and many of his older brothers were forced to quit school early to work on the farm. Eventually, the family left Alabama and moved to New Jersey, becoming part of the Great Migration, the movement north and west of millions of African-Americans out of the South from 1916-70. Herman grew up in Farmingdale, New Jersey.

“We wanted another way of life, so we migrated to New Jersey,” Hill’s younger brother, Jack, said. “Things were better here in Jersey. There were more things to do. More job opportunities so you could take care of your family more. We all left the South and came up here.”1

Of the 15 children, the last three, including Jack, earned college degrees and became teachers. Some of the older siblings who’d left school early in Alabama wound up attending trade schools in New Jersey. Aside from Herman and Jack, who attended college in Minnesota, all of the Hill siblings lived the remainder of their lives in New Jersey, and Jack returned after college.

From a young age, Herman knew he wanted to become a professional baseball player, Jack said. For a while, however, his path was delayed, as Hill suffered from whooping cough when he was young and missed what would have been his entire year of kindergarten because he was ill. His mother then held him out of school a second year so he could gain strength and be better prepared for school. So once he began going to school, he was two years older than most of his classmates. Soon enough, he began to catch up not only in school but also with his baseball dreams, too. When he was in eighth grade, he was invited to a tryout by the Baltimore Orioles, according to Jack.

“He was a very, very good athlete in football, basketball and baseball. But he loved baseball,” Jack said. “Whenever it was awards day in school, he’d get an award for perfect attendance. He had perfect attendance all the way through eighth grade until that day. He finally missed school on the day he went to try out for the Orioles.”2

Hill didn’t sign with the Orioles but developed into a stellar 6-foot-2, 190-pound athlete at Southern Freehold High School (now known as Howell High School). He earned varsity letters in baseball, basketball and football and was an all-state halfback in football and all-state outfielder in baseball. He was inducted into the high school’s athletic Hall of Fame in 1993. His Hall of Fame plaque, including a photo of him in a Twins uniform, hangs in a hallway in the school.

That is not the only way Hill is recognized at Howell High School, though. Today, the Herman Hill Award is given annually to the school’s male athlete of the year.

“It’s the most prestigious award we give to our male athletes,” athletic director Pete Meehan said.3

While in high school, Hill also played on amateur baseball teams with older ballplayers along the Jersey Shore and elsewhere in New Jersey. “Someone would look at him and figure he was too young to play, then people would say, ‘Have you seen him play?’”4 Jack Hill said.

Herman threw right-handed and also was initially a switch-hitter but turned into an exclusively left-handed batter. Early on, he was a strikeout pitcher, but Hill’s strength was his speed and he became a full-time outfielder. He later was timed at 9.5 seconds in the 100-yard dash and at 3.4 seconds running from home plate to first base.5

Jack, who was two years younger than Herman and ended up in the same high school graduating class, was a small-college, multi-sport athlete at Bemidji State in Minnesota. “I went to school at Bemidji and a lot of kids there knew my brother or of him, because he played for the Twins. They had pictures of him; some had had their pictures taken with him. They would ask me if I was faster than he was, because I ran track in college. I said no, I couldn’t catch him. He was in another class.”6

That speed, and his ability to hit left-handed, continued to attract attention from major league teams. “And along came the Minnesota Twins. They started following him, talking to him,” Jack recalled. “Then they came to our house, visited with our mother and father. When they came, they brought a contract with them. My mother said, ‘Well, if that’s what he wants to do, OK, let him sign it.’ He graduated from high school on Wednesday and by Saturday he was in training camp.”7

The scout was Jack McKeon, who told the story himself at age 88 in 2019. McKeon, himself a New Jersey native, said, “My first real scouting job was in ’65 when I scouted for the Twins in Jersey.’’ He recommended that Minnesota draft Steve Garvey in June 1966 (Garvey opted for college instead), as well as Steve Braun (who signed with the Twins). McKeon added, “The first kid I ever signed was a free agent named Herman Hill out of Freehold. I remember no other scouts wanted him. I said, ‘I really like this guy. Give me $500 to sign him.’”8

Hill was 20 years old when he graduated from high school in 1966 because of the two years he missed when he was young. Once in the minors, realizing his ambition of becoming a professional baseball player, he didn’t miss many steps. He ascended rapidly through the Twins’ farm system, earning accolades in annual Twins media guides and in the leagues where he played.

His first assignment was at Sarasota, Florida, where he hit .222 in 45 games for the Twins’ rookie league team in 1966. In a full season at Class A Orlando in 1967, he finished third in the Florida State League batting race with a .292 average, led in on-base percentage and stole 58 bases. The Twins credited him with leading Orlando to the Eastern Division championship.9 Topps named him its Florida State League player of the month for July and he was named to the league’s all-star team at the end of the season.

Jack McKeon’s vivid recollection continued (though after more than 50 years he was fuzzy on the details). “He went down to their Rookie League and I get a call from [Twins farm director] George Brophy and he said, ‘Your guy, he’s not very good. We’re going to have release him.’ I said, ‘Are you crazy? The guy is 6-foot-4, a switch-hitter, runs like a deer.’ So they didn’t release him, sent him to the Florida State League instead, and he ended up leading the league in hitting. So a year later George Brophy calls me back and says, ‘Hey Mac, your guy is pretty good.’ I said, ‘Yeah, no (expletive). And you were going to release him.’”10

In 1968, Hill played at three levels, led one league in stolen bases and nearly led another. He hit .341 and stole 12 bases in 14 attempts in 23 games for Wilson of the Class A Carolina League. Promoted to Class AA Charlotte in the Southern League, he had 36 steals, missing the stolen-base crown by one. That fall, he played in the Florida Instructional League, hit .370 and had a league-leading 16 steals. That gave him 64 steals for the season with three teams.

The Twins were taking notice. The 1969 media guide called him “an exciting, colorful performer,” who “impressed all observers with his [1968] spring training play, and then proceeded to make great strides up the professional ladder during the regular season.”11

In 1969, Hill had a stellar season at Class AAA Denver of the American Association. He batted .300 in 135 games, stealing 31 bases, hitting 21 doubles, eight triples, and six home runs. He scored 90 runs. He led the league’s outfielders in putouts. Through mid-summer, he was not hitting as well as he wanted, but found another way to turn his speed to his advantage: He honed his bunting skills. “I was hitting .267 [in July] when I started bunting more,” and became a .300 hitter, Hill said the next spring. “So there’s no telling what I could have done had I bunted all year.”12

He was one of the “most exciting players” in the American Association, the Twins thought.13 They made him one of seven players called up for the final month of the 1969 season. As the Twins locked up the American League West Division title, Hill played in 16 games, 13 of them as a pinch-runner.

To stay in baseball shape, Hill played for the Estrellas team in the 1969-70 Dominican winter league season. It was common at the time for ballplayers trying to make major-league rosters to play winter ball to work on their skills and stay in condition. And it was perhaps especially important for Hill, given the strength of the Twins roster he was trying to break into.

The 1969 and 1970 Twins were among the best teams in baseball, winning the AL West Division title both years, and boasting three Hall of Famers and several past and future MVPs, Cy Young winners, and batting champions. Their starting 1969 outfield included veteran left-handed hitters Tony Oliva, a three-time batting champion, and Ted Uhlaender. Although Hill hoped to hit .340 at Denver in 1970 and give himself a better chance at sticking with the major league team, he was one of several young left-handed batting outfielders or infielder-outfielders vying for roster spots. After the 1969 season, one of them, Charlie Manuel, lamented that “anytime you get guys like Jim Holt, Herman Hill, and Graig Nettles, you don’t have a cinch job on the team.”14

Uhlaender and Nettles were traded after 1969, clearing some of the logjam. But it was Holt, who’d hit .336 in Denver in 1969, who emerged among the other young left-handed hitters and outfielders to play regularly in 1970.

Hill returned to the Twins’ Class AAA, now in Evansville, Indiana. He stole 24 bases and hit eight triples, but his batting average dropped to .248. Still, he was called up twice by the Twins in 1970—in late June/early July, and September.

This time, he got more at-bats, although still not many. He played 27 games, made 23 plate appearances, batted .091 and scored eight runs but had no stolen bases. In his second-to-last appearance, on September 30, Hill pinch-ran for Harmon Killebrew in the bottom of the ninth. He scored on Paul Ratliff’s walk-off, three-run homer as the Twins defeated Kansas City, 6-4.

Less than a month later, October 20, 1970, Hill was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals, along with minor-league shortstop Bob Wissler, for reliever Sal Campisi and infielder Jim Kennedy.

Campisi was the key to the deal for the Twins, a right-handed pitcher who had had a solid 1970 season but suffered a back injury. Twins beat writer Bob Fowler thought it was a good move for the Twins, saying Hill’s .091 batting average meant they didn’t have to gamble away much to pick up Campisi, who could bounce back from the injury.15 What Fowler didn’t mention was that Hill’s batting average came in only a small sample of at-bats. The Cardinals, meanwhile, seemed pleased with their end of the trade, calling Hill “a fine prospect.”16 (Fowler’s hunch turned out wrong: Campisi appeared in only six games for the Twins in 1971, pitching 4 1/3 innings before his career came to an end.)

Although the Twins had a full outfield, Herman Hill did not expect the trade, his brother said. He had made good friends and bonded well with several Twins players.17

“I think he was surprised because he was good friends with Tom Hall, who was a pitcher. He and my brother got called up at the same time. He was also close to Rod Carew and roomed sometimes with Tony [Oliva].”18

As he had after 1969, Hill headed south following the 1970 season for more winter-league ball. This time, he played for the Magallanes Navigators in the Venezuelan League. The team was managed by former major-league pitcher Carlos Pascual. Among Hill’s teammates at the start of the season were major leaguers John Morris, Orlando Pena, Cito Gaston and his teammate with the Twins, Jim Holt.19

Through 36 games, Hill was hitting .252, with seven stolen bases. He scored 23 runs, had 19 walks, and 29 strikeouts.20

On December 14, the team had an off-day and Hill joined other teammates for a trip to the beach, swimming in the Caribbean Sea near Maracaibo. Maracaibo is on Venezuela’s northern coast, less than 200 miles from the popular tourist island of Aruba. The December 26, 1970, issue of The Sporting News contained a fairly graphic and somber account of what happened next:

“Hill, playing for Magallanes in the Venezuelan League, was enjoying a day off at the beach when he was swept out to sea by a large wave.

“Eduardo Moncada, The Sporting News correspondent in Venezuela, said Hill had gone to the beach with teammates Dale Spier, John Morris, and Ray Fosse.

“When Hill was swept into the sea, the others tried to save him. Morris, in struggling with Hill, lost three teeth. Fosse managed to save Morris when Hill apparently disappeared. Spier, in the meantime, found himself in difficulty, but managed to reach shore.

“Venezuelan marines searched for the body, but it was not found immediately.

“A 6-2 athlete, Hill was considered an above-average prospect by the Cardinals. …”21

In an ensuing story, the Cardinals said they were shocked by Hill’s death.22

At Bemidji State, located in forested north-central Minnesota 220 miles north of Minneapolis, it was the last day before the school’s holiday break. Jack Hill had taken his last final exam and gone back to his place for supper, then planned to attend a Bemidji State hockey game that night. He was scheduled to fly home to New Jersey the next day.

“I was at my place and I had finished supper. Bemidji is a big hockey school, and I had decided to go watch the hockey game that night. So I was cleaning up after supper and getting ready to go to the hockey game when the phone rings.

“It was my sister calling me. She asked me when I was coming home. I said ‘my flight leaves tomorrow.’ She said, ‘You need to come home now, tonight.’ Then she started crying and couldn’t talk anymore and my other sister got on the phone and she said Herman had been killed. I said ‘What?’

“My roommates heard me scream, then crying. They said ‘what’s wrong?’ I had a picture of Herman—in his baseball uniform—on my dresser. I pointed to it. I said, ‘My sister is on the phone telling me my brother got killed.’ They said ‘Herman? Herman’s dead?’”23

Jack was stunned. “I was shocked to the point of where all I could say was I couldn’t believe it.”24

Jack said it was too late to schedule a flight out of small and rural Bemidji, so he stayed with his plan to leave the next day. But he was so numbed, all he could think of was to go to the hockey game so he wouldn’t be alone in his grief. Some people had already heard about Herman’s death and offered condolences. Others hadn’t and wondered why Jack looked so glum. “My friends said, ‘His brother has died.’ People said, ‘You mean Herman?’ Because that was the only one they knew. The next day it was on the front page of the newspaper.”25

On the flight back to New Jersey, other passengers noticed a sad-looking Jack Hill and asked if he was all right. He carried a newspaper with him and would hold it up, and say, “That’s my brother. We were very close.”26

Herman Hill’s death tore through his family: a promising young life, a young man who’d already overcome childhood adversity, died thousands of miles from home.

“The death of my brother hit my mother so hard,” Jack said. “We all say now that we don’t think she ever recovered. You could tell, even in her actions, it just affected her so much. He was taken away at such a young age, she never got over it.”27

While not to the extent of a mother’s grief, others had a hard time getting over it, too.

In 2003, another of Hill’s teammates in Venezuela, Gregorio Machado, told the writer Alfonso Tusa that it had been payday shortly before the team traveled to Maracaibo. Since players were taking a bus for the road trip, some thought they could also go shopping in the nearby city of Maicao. “We had a practice that day. … [Then] while eating lunch they decided to go to the beach. Dale Spier, Ray Fosse, John Morris, and Herman Hill.”28 Hill was with his girlfriend and the other three with their wives.29

Machado told Tusa that Hill’s autopsy revealed he had a stroke, which led him to shout for help. “I remember that Morris lost his teeth because he tried to rescue Hill. When Hill went into the sea and started to scream, Morris went behind and got to grab him. But Hill slipped from his hands. Because of this Morris felt guilty about Hill’s drowning.”30

Hill’s body was recovered three days later, Machado said.

Slightly more than three years later, another American ballplayer, minor league pitcher Mark Weems, drowned January 1, 1974, in the waters of Patanemo Bay, also off the north coast of Venezuela but farther east than the site of Hill’s drowning. Weems was playing for the same team Hill had been, the Magallanes Navigators.31

Hill’s legacy exists not only in the Herman Hill Award, but other ways. After Jack Hill retired from teaching, to stay busy he took a job at the Six Flags amusement park close to where he lives. A co-worker whom he visited with regularly for a couple of years one day recalled there used to be a Hill who was a ballplayer, Herman Hill. He asked if Jack was related. “I was his brother!” It turned out that the co-worker collected baseball cards and the next day brought several Herman Hill Topps cards to work and showed them to Jack. “I used to follow him,” the man said.32

On a larger scale, Herman Hill’s death happened within a few years after the players union and major-league owners signed the first two Basic Agreements of the Marvin Miller era. The new agreements included changes in benefits for players, among them increases in pensions and life-insurance benefits. Hill’s name was mentioned as an example of how collective bargaining had helped players: the number of days a player was required to be on a big-league roster for insurance-coverage eligibility was reduced, while the death benefit was increased. Because Hill “just had qualified for coverage by putting in 60 days in the major leagues [by the fall of 1970], his family received $100,000 in death benefits.”33 In other words, Hill’s death made him one of the first symbols of the advances the Major League Baseball Players Association was making on behalf of the players. That, too, is part of the legacy of a ballplayer who, even with a short career, had an effect on the people he knew and on many he never lived to meet.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Jack Hill and Audrey Hill for their time and sharing information and memories.

Thanks also to Ian Kraft of the Minnesota Twins communications department and Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Online

The Sporting News via SABR.org/paperofrecord

Major League Baseball Players Association’s official history and timeline

Hill family obituaries via https://www.findagrave.com

Notes

1 Jack Hill, telephone interview with Dana Yost, April 2, 2019 (hereafter J. Hill-Yost interview).

2 Ibid.

3 Pete Meehan, telephone interview with Dana Yost, April 1, 2019.

4 J. Hill-Yost interview.

5 John Swagerty, “Wichita Off to Strong Start in AA Gate Derby; Bunt Hill’s Weapon,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1970, 2.

6 Ibid.

7 J. Hill-Yost interview.

8 Keith Sargeant, “Jack McKeon takes a job with Washington Nationals at 88,” NJ.com, January 31, 2019 (https://www.nj.com/sports/2019/01/jack-mckeon-takes-a-job-with-washington-nationals-at-88-why-the-nj-native-feels-spry-15-years-after-beating-the-yankees.html)

9 Minnesota Twins 1968 media guide, 32.

10 Sargeant, “Jack McKeon takes a job with Washington Nationals at 88.”

11 Minnesota Twins 1969 media guide, 38.

12 Swagerty, “Wichita Off to Strong Start in AA Gate Derby; Bunt Hill’s Weapon.”

13 Minnesota Twins 1970 media guide, 38.

14 Mike Lamey, “Oh-for-35 at Dish—But Manuel Vows to Sock the Curve,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1969, 32.

15 Bob Fowler, “.325 Average Fails to Satisfy Oliva,” The Sporting News, November 7, 1970, 43.

16 Neal Russo, “45 Percent Redbird Turnover; Time for Bing to Take a Breather,” The Sporting News, December 26, 1970, 45-46.

17 Mike Lamey, “Third Chance for Holt,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1970, 12. This story is one example of Hill’s friendships with teammates. Lamey captures the easy-going camaraderie shared between Hill and teammates in the Twins’ clubhouse. Both Hill and Holt, fighting for a roster spot, share jokes as they play cards, and include Lamey into the light-hearted conversation.

18 J. Hill-Yost interview.

19 Winter league rosters, The Sporting News, October 31, 1970, 55.

20 Alfonso L. Tusa, “Homenaje a Herman Hill (A Tribute to Herman Hill),” seamheads.com, December 15, 2008.

21 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, December 26, 1970, 53.

22 Russo, “45 Percent Redbird Turnover; Time for Bing to Take a Breather.”

23 J. Hill-Yost interview.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Tusa, “Homenaje a Herman Hill (A Tribute to Herman Hill).” Various sources say Hill suffered a stroke in the water. Another, also citing the autopsy for the stroke cause, is “Las trágicas y absurdas muertes de peloteros en la historia de la LVBP (The Tragic and Absurd Deaths of Players in the History of the LVBP),” Tenemos Noticias, December 8, 2018.

29 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News. Tusa, “Homenaje a Herman Hill (A Tribute to Herman Hill).”

30 Tusa, “Homenaje a Herman Hill (A Tribute to Herman Hill).”

31 “Las trágicas y absurdas muertes de peloteros en la historia de la LVBP (The Tragic and Absurd Deaths of Players in the History of the LVBP).” Mark Weems biographical information, baseball-reference.com.

32 Ibid.

33 Bob Broeg, “’46 to ’62…It’s a Long Way in $$,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1972, 24, 30. Also, background from the Major League Baseball Players Association’s collective-bargaining history and basic agreements.

Full Name

Herman Alexander Hill

Born

October 12, 1945 at Tuskegee, AL (USA)

Died

December 14, 1970 at Valencia, Carabobo (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.