Steve Garvey

Steve Garvey was the epitome of the Southern California cultural icon in baseball spikes. Photogenic, fan-friendly, and media accessible, he projected the image of an All-American success story and devoted family man. As a Los Angeles Dodger in 1974, he won the National League Most Valuable Player Award after starting the All-Star Game at first base as a write-in candidate. In 1984, then a member of the San Diego Padres, he delivered a clutch home run at a critical moment in the National League Championship Series. During the intervening decade, Garvey rapped 1,995 base hits and drove in 1,025 runs for a sterling .303 batting average. By the end of the 1980s, however, his baseball career was a fading memory and his image became that of a human being who erred like any other.

Steve Garvey was the epitome of the Southern California cultural icon in baseball spikes. Photogenic, fan-friendly, and media accessible, he projected the image of an All-American success story and devoted family man. As a Los Angeles Dodger in 1974, he won the National League Most Valuable Player Award after starting the All-Star Game at first base as a write-in candidate. In 1984, then a member of the San Diego Padres, he delivered a clutch home run at a critical moment in the National League Championship Series. During the intervening decade, Garvey rapped 1,995 base hits and drove in 1,025 runs for a sterling .303 batting average. By the end of the 1980s, however, his baseball career was a fading memory and his image became that of a human being who erred like any other.

In a Tampa hospital on December 22, 1948, Joseph and Mildred Garvey welcomed the birth of their only child, a son they christened Steven Patrick. Both Joe and Millie were transplanted Long Islanders and Joe passed on his love of baseball, and specifically the Brooklyn Dodgers, to young Steve:

“I always had balls available for me because we had 11 grapefruit trees in the backyard. In the spring I’d take the little hard grapefruits that had fallen off and I’d hit them with a broomstick. I’d be the whole Dodgers lineup … Neal, Gilliam, Campanella, Snider, Hodges.”1

Fate smiled on Joe Garvey, a bus driver for Greyhound, when in March 1956, he was assigned to drive the defending world champion Brooklyn Dodgers to spring training in Vero Beach. Joe asked permission for his 7-year-old son to be the Dodgers’ batboy. It was a position young Steve held for the following six springs whenever the Dodgers came to Tampa.

One particular player impressed Steve both on and off the field. As Mort Zachter chronicled in his biography of Gil Hodges, Steve was amazed at how the taciturn first baseman “always seemed to have time for autograph requests … asking how he was doing in school and Little League, and even taking a few minutes to play catch with him.” Zachter identified Hodges as the player Steve intended to emulate.2 Millie Garvey remembered the ambitions of her young son:

“Steve was about nine or ten when we asked what he would like for Christmas. He said a new baseball glove … but when I asked him where he’d seen the glove [he wanted] and how much it cost, he told me $25. I was shocked. That was a lot of money and I told him so. He said, “Mom, look at it this way: $25 now will bring $25,000 later on.”3

Though Garvey was small for a high school athlete at 5-feet-7 and 165 pounds, that did not prevent him from excelling at Chamberlain High, both on the diamond and the gridiron. Batting .472 in his junior year and .465 as a senior attracted the attention of scouts throughout Organized Baseball, as well as Danny Litwhiler, head coach at Michigan State University.4 Garvey rejected an offer from the Minnesota Twins in 1966 to play for Litwhiler in East Lansing.

The Dodgers’ selections in the 1968 amateur drafts are considered to be the greatest in the history of the sport. Then based in Los Angeles, the Dodgers drafted Davey Lopes in January before selecting Bill Buckner, Ron Cey, Tom Paciorek, Joe Ferguson, Bobby Valentine, Geoff Zahn, and Doyle Alexander in June.5 The Dodgers’ shopping spree continued when, in the first round of the secondary phase, they drafted Steve Garvey. Litwhiler gave a glowing report of his young third baseman:

“Steve was an awesome hitter in college. He hit towering home runs. But it was his mental toughness that was so impressive. He could accept the defeat of striking out. … My only question about his making it was his defense. He didn’t have the arm for left field. He was acceptable at third, but no more than that.”6 After Garvey spent parts of two seasons at Ogden and Albuquerque, the Dodgers deemed his skills ready for the major leagues. At Albuquerque in 1969 Garvey batted a robust .373 with 18 doubles, 14 home runs, and 85 RBIs in the thin New Mexico air, and the Dodgers called him up. In his major-league debut, on September 1, Garvey struck out against Jack DiLauro of the New York Mets as the Dodgers defeated the eventual world champions, 10-6.7

The dawning of a new decade brought challenges to Garvey’s burgeoning baseball career. A college football injury limited his fielding range as a third baseman. When he began the 1970 season 2-for-23, he was optioned to Spokane at the end of April.8 Recalled after the rosters expanded in September, Garvey managed to improve his average to .269, but his fielding remained a problem. With 14 errors at the hot corner in 1971, hecklers began to chant, “When Steve Garvey plays third base, it’s Ball Night at Dodger Stadium.”9 To make matters worse, a Mike Marshall screwball fractured his wrist in June, sidelining him for five weeks.10 In only 85 games in 1972, Garvey made a league-leading 28 errors.11 Rumors began to circulate that his days in the Dodgers’ organization were numbered.

It was the benevolence and ingenuity of a Dodgers teammate that led to Garvey’s break at stardom. Steve began the 1973 season on the bench and remained there through the end of June. As the team suited up for a June 23 contest against the Cincinnati Reds, manager Walter Alston was faced with lineup issues. With Von Joshua and Manny Mota both injured, who was going to play left field? Bill Buckner remembered:

“The Dodgers tried Steve Garvey at third base and at left field. Except for pinch-hitting, his career was not looking too well. He could play some first base at Albuquerque [in 1969] and he played well. I suggested this to Alston and rest assured, I never played first base again. Alston moved me to left field.”12 The experiment worked. Although Buckner continued to see action at first base, Garvey batted .304 while improving his fielding percentage to .993 after the transition to first base.13 Meanwhile, Garvey’s personal life was changing. He graduated from Michigan State with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1971; on October 29 that year, he married Cynthia Ann Truhan.14

After eight years in the wilderness, the Dodgers were ready to contend again in 1974. They traded for Jimmy Wynn from Houston, Mike Marshall from Montreal, and by June commanded a torrid eight-game lead over Cincinnati.15 As for Steve Garvey, expectations were modest to the point that his name was not even included on the All-Star Game ballot. That’s where the new first baseman defied all odds. By June Garvey was batting .338 with 11 home runs and 46 RBIs.16 Fans began to notice, and in the weeks leading to the All-Star Game on July 23, Garvey was receiving nearly as many votes as Tony Perez. In the end, Garvey beat Perez by nearly 20,000 votes. It was only the second time in baseball history (Rico Carty in 1970 was the first) that a player was voted to start an All-Star Game without appearing on the ballot.17

At the game in Pittsburgh, Garvey went 2-for-4 with a single against Gaylord Perry and a double against Luis Tiant. Augmented by some fancy fielding in the 7-2 victory for the National League, he was named the All-Star Game’s Most Valuable Player.18 Even more impressive, Garvey was ill and remembered “my mouth was full of cotton, all dry from the antibiotics,” when Commissioner Bowie Kuhn presented the Arch Ward Trophy to him.19

For the regular season, Garvey led the Dodgers to a division title with 200 hits, 21 home runs, and 111 RBIs, scoring 95 runs, batting .312, and making only eight errors at first base.20 The Dodgers dispatched the Pirates three games to one in the National League Championship Series, highlighted by a 12-1 barrage in the deciding Game Four. Garvey hit a pair of two-run home runs and captured the NLCS MVP.21 Although the Dodgers lost the World Series to the Oakland A’s, Garvey capped his 1974 campaign by winning the National League MVP as well. Perhaps most noteworthy given the obstacles earlier in his career, Garvey won the first of four consecutive Gold Glove Awards at first base.

Not everybody agreed with Garvey’s selection. Finishing second with 233 votes to Garvey’s 270 was Lou Brock of the St. Louis Cardinals.22 Although he set a new single-season record with 118 stolen bases, the achievement was underplayed by many of the writers. As Brock remarked in 1975, “a good deal of it had to do with … the old prejudice … about base stealers … that they do it for personal gain, not for the welfare of the team.”23 He continued, “It’s true I didn’t win it, but it’s not true I lost it. I earned it.”24 The MVP fracas was Garvey’s first introduction to controversy. It would not be his last.

At 25, Garvey had developed into one of the most consistent players in the National League. Yankees scout Clyde Kluttz even compared him to “a right-handed Lou Gehrig.”25 Batting .319 in 1975 and .317 in 1976, Garvey recorded only three errors in over 1,500 chances in the Bicentennial year.26 On September 3, 1975, after sitting out the day before, Garvey played the first of 1,207 consecutive games. Garvey was Lou Gehrig. Along with Davey Lopes, Ron Cey, and Bill Russell, he formed part of a Dodgers infield that remained ironclad until 1981.Garvey was selected to the All-Star Game each of those years. In 1977 the Dodgers rewarded their superstar, now the father of two young daughters, with a six-year, $1.971 million contract that expired in 1982.27Garvey hit 33 home runs in 1977, one of four teammates to reach the 30 plateau in a season the Dodgers returned to the World Series under new manager Tommy Lasorda. Off the field, Garvey took his star to Hollywood in 1975 when he was featured in the television movie Hey Coach. Appearances on The Mike Douglas Show, Fantasy Island, and the Mickey’s 50 documentary about the Disney character soon followed.

Garvey’s rise to stardom could not have been better timed. As the decade of the 1970s evolved, millions of young Americans grew weary of the constant images of explicit violence, illicit drug use, and gratuitous sexuality, not to mention higher taxes on stagnant wages. Paradoxically and in spite of the permissiveness of the times, they began to gravitate toward more traditional values and ideals. William C. Berman chronicled this political phenomenon in his book America’s Right Turn. Berman described the young Americans as “militants” and observed this conservative revival among Democrats as well as Republicans, transpiring in all 50 states, “…not just in the sunbelt.”28 Berman continues:

“Those militants … were engaged in a cultural civil war … over such matters as the definition of the family, the content of public education, the role of the media … and the various court definitions affecting personal values.” These debates “touched on longstanding national conflicts, which were rooted in the profoundly different belief systems and operating codes separating moral traditionalists from social liberals of a secular persuasion.”29

Not surprisingly, Berman’s “moral traditionalists” were dissatisfied with acceptance of the rebel and the scofflaw as protagonists in sports and entertainment, while authority figures including police officers were now considered to be antagonists. They sought heroes who reflected their values. In an era when outspoken iconoclasts like Reggie Jackson, Dave Kingman, and Dave Parker dominated the headlines, the populist right became more comfortable with the wholesome images of Nolan Ryan, Gary Carter, and George Foster. In football, Roger Staubach raised eyebrows when he proclaimed that “I like sex as much as Joe Namath does; I just have it with one woman.”30

In was amid this political climate that as “the Gipper” ran for president, “Steve Garvey, All American” became a star both at Chavez Ravine and on Madison Avenue. Garvey was well dressed and clean shaven with every hair in place and did not chew tobacco, swear, or wear jeans. Garvey attended church frequently, was always available to the media for a quotation, helped elderly women across the street, and signed thousands of autographs until every kid had one. A school in the San Joaquin Valley even rededicated itself as the Steve Garvey Junior High School. Tommy Lasorda remarked that “if [Garvey] ever came to date my daughter, I’d lock the door and not let him out.”31 Even in Cincinnati, young Petey Rose came to dinner one night wearing a Steve Garvey T-shirt until his father made him change into a Pete Rose T-shirt.32

Although Los Angeles fans and media loved him, Garvey had hordes of adversaries in other National League cities and those in the Dodgers clubhouse who were watching his every move. Joe Garvey conveyed that his son’s image was nothing new — even in high school during the turbulent 1960s he wore slacks and monogrammed sweaters.33 The observations of the elder Garvey, however, did nothing to convince his son’s Dodgers teammates of his authenticity.

As early as 1975, Betty Cuniberti of the San Bernardino Sun wrote that Garvey “doesn’t have a friend on this team.34 As someone who did not smoke or drink, the perception was that Garvey was judgmental of teammates who did. Several teammates were resolute that Garvey’s photographs and autographs were not initiated on his own volition, but rather as a means to gain popularity in order to generate endorsements.”35 Cynthia even pleaded with him, “[C]ouldn’t you drink a beer or two? They’ll like you better.”36 As a member of the Chicago Cubs in 1986, Davey Lopes expressed where he and his teammates were coming from:

“The problem was that he was presented as better than we were. The press did that. The organization did that. Nobody can question that Garv came to play. … It was all the other stuff. It created a tension that never went away, that never eased.”37

In 1977, Garvey underwent a colossal slump, batting only .205 in 45 games from July 4 through August 24.38 Although his batting average recovered, it was the only season between 1974 and 1980 in which he failed to hit .300. There was more than enough perverse pleasure in the Dodgers clubhouse when Garvey hit into a double play or was thrown out at home plate. He hit .316 with 202 hits and 113 RBIs in 1978, but again found himself at the center of controversy when teammate Don Sutton agreed to an interview with Thomas Boswell of the Washington Post at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia.

A mercurial personality from rural Alabama, Sutton was not convinced that the media image of his first baseman was the genuine article. As Sutton told Boswell on August 15, “[A]ll you hear about on our team is Steve Garvey, the All-American boy. Well, the best player on this team for the last two years — and we all know it — is Reggie Smith. As Reggie goes, so [go] us. … Reggie doesn’t go out and publicize himself. He doesn’t smile at the right people or say the right things. He tells the truth, even if it sometimes alienates people.”39 Five days passed without controversy but on August 20, as the Dodgers prepared to play the Mets at Shea Stadium, Garvey expressed displeasure to Sutton over his published remarks:

“We are a team,” he reminded the pitcher, adding, “If you have something to say to me, say it to my face.”40 There are different interpretations of the events that followed but all parties agree that within moments, Steve Garvey and Don Sutton fell to the floor in a battle royal, “clawing and scratching each other.”41 The press dubbed the incident “the Grapple in the Apple.” Milton Richman, who covered the incident for United Press International, recalled seeing that Sutton “leaped at Garvey and shoved him into the lockers.”42 As four of the larger players on the team separated the two, Joe Ferguson remarked that if the fight continued, “maybe they’ll kill each other.”43

A bruised eye did not prevent Garvey from completing a sterling season for the Dodgers: “Afterwards I went out and got a couple of hits against the Mets, and hit something like .430 [actually .369] for the rest of the season.”44 Much like the 1974 season, Garvey won the MVP Award in both the All-Star Game and the NLCS. At the All-Star Game in San Diego, he rapped a two-run single in the third inning before igniting an eighth-inning rally with a triple to win the game, 7-3.45 In the NLCS, Garvey hit four home runs and a triple in a 3-games-to-1 win over the Phillies.46 For the third time in five years, however, the Dodgers lost the World Series. After losing a one-game playoff to the Astros in 1980, the Dodgers behind rookie ace Fernando Valenzuela were once again poised for greatness in 1981.

The new decade brought more opportunities for Steve Garvey, both on Elysian Park Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard. In 1980, he played a cameo role in The Gong Show Movie. The following year, he hosted The Steve Garvey Celebrity Sports Classic for the Multiple Sclerosis Society, his favorite charity. Notwithstanding a midseason strike that eliminated two months of the season, Garvey batted only .283 with 10 home runs and 64 RBIs. With the Dodgers having clinched the first half before the strike, Garvey saved his heroics for the postseason. Entering Game Four of the NLCS, he hit safely in every playoff contest.47 Everyone remembers the Rick Monday home run, but in Game Four Garvey put the Dodgers ahead, 3-1, with a two-run homer off Montreal’s Bill Gullickson. After losing to the Yankees in 1977 and 1978, the Dodgers finally defeated the Bronx Bombers to win the World Series in 1981.

Expectations were high on the Dodgers to repeat as world champions in 1982. Uncharacteristically for an impending free agent, meanwhile, Garvey suffered an off-year, failing to reach .300, 200 hits, 20 home runs, or 100 RBIs.48 Under general manager Al Campanis, signing the team’s own free agents did not comply with the Dodger Way. Since players earned the right to free agency, the only Dodgers free agent to re-sign with Los Angeles had been Bill Russell in 1980.The team had traded Davey Lopes to the Oakland A’s in spring training and would trade Ron Cey to the Chicago Cubs in 1982. Meanwhile, first-base prospect Greg Brock was tearing up the Pacific Coast League, batting .310 with 44 home runs for Albuquerque.49 Garvey remembered the negotiations with the Dodgers:

“Final offers had to be made. [Peter O’Malley] said his final offer was $5 million for four years, no incentives. We drew the line at $6 million for four years.”50 The erstwhile Brooklyn batboy would not be a Dodger for life, instead on December 21 signing a five-year, $6.6 million contract with the San Diego Padres.51 Ever conscious of his image, Garvey chuckled that he “looked like a taco” when he first adorned the yellow and brown colors of his new team.52 By now, Garvey was also beginning a new chapter on his personal life, as his marriage to Cynthia had ended.

On April 15, 1983, Garvey returned to Dodger Stadium as a member of the Padres to a chorus of 53,392 cheering fans.53 Though he was hitless in four at-bats, the contest was significant as it was Steve’s 1,117th consecutive game, tying Billy Williams for the National League record. Garvey extended the streak an additional 90 games, to 1,207.54 He was batting .294 with 14 home runs and 59 RBIs on July 29, the night the streak ended painfully:

On April 15, 1983, Garvey returned to Dodger Stadium as a member of the Padres to a chorus of 53,392 cheering fans.53 Though he was hitless in four at-bats, the contest was significant as it was Steve’s 1,117th consecutive game, tying Billy Williams for the National League record. Garvey extended the streak an additional 90 games, to 1,207.54 He was batting .294 with 14 home runs and 59 RBIs on July 29, the night the streak ended painfully:

“I was at third. One run was in and we had two men out. The second pitch to Garry Templeton was a fastball, way up. Bruce Benedict, the [Atlanta] catcher, never touched it, and I headed for home.” Ninety feet later, pitcher Pascual Perez tagged him at the plate, “I put my hand back for support and felt my thumb — something happened.”55 Garvey broke his thumb in the collision and was out for the remainder of the season.

Manager Dick Williams observed that “Steve did help us” in his truncated 1983 campaign. “He worked hard, influenced the kids, and made it easier for us to get rid of more veterans who weren’t producing.”56 Two new veterans who did produce in 1984 were Yankee imports Graig Nettles and Goose Gossage. Together with a core of young players centered on Tony Gwynn, the Padres were about to shed their reputation as divisional doormats, reaching the postseason for the first time in their history.

Garvey recovered from his thumb injury to play the entire 1984 season without committing an error.57 Though he was named to start the All-Star Game, his offensive numbers continued to decline; he batted.284 with only eight home runs. Williams wondered if Garvey “left his best days at Dodger Stadium.”58

That question would be answered in the NLCS against the favored Chicago Cubs, winners of the first two contests. Facing elimination, the Padres won Game Three, 7-1, to set the stage for a monumental Game Four on October 6. In the words of his manager, Garvey “controlled nine innings of baseball like few other hitters in the history of the game.”59

The game was scoreless until the third inning; after Tony Gwynn broke the stalemate with a sacrifice fly, Garvey drove in the second run with a two-out double. The Cubs scored three but the Padres forced a tie in the fifth when Steve singled in Tim Flannery. San Diego extended its lead to 5-3 in the seventh but the Cubs scored two in the eighth off Gossage to tie once again. Lee Smith was brought in to pitch the ninth for the Cubs. If the Padres lost, they would go home. With one out, Tony Gwynn was on first with Garvey at the plate and Williams in the dugout:

“There was no way Garvey could pull us out of the fire once more and — BOOM! — my thoughts were interrupted by the loudest crack I ever heard. Then I saw the white ball heading towards the right center field fence. … It really was going out of the ballpark, wasn’t it? It was! After what felt like forever, the ball dropped into the stands and Garvey had his homer.”60 The Padres won, 7-5, on Garvey’s home run and after winning the following night, they were going to the World Series. Garvey took home his third NLCS Most Valuable Player Award. More than three decades later, Padres fans consider the home run to be the greatest moment in franchise history. Legend had it that on an inbound flight to San Diego not long after, the in-flight service showed The Natural; during the famous home-run scene, passengers actually began to chant “GAR-VEY! GAR-VEY!”

The cultural divide between Garvey and his teammates remained pronounced in San Diego, but the players were able to resolve it in a more pleasant way. Goose Gossage remembered a swimming pool party at his home:

“On this particular evening … Steve looked a little too suave for his own good. As he walked past the swimming pool, several guys tossed him into the shallow end. Head first. When Garvey came up for air, every hair was still in place. ‘Perfect,’ I muttered. ‘Steve Garvey has to be the only guy in the world who could get tossed in a swimming pool and come out looking the same way he did going in.’ ”61

Although Garvey batted an even .300 during the 1984 World Series, the Padres lost in five games to the Detroit Tigers. By 1987, a damaged tendon in his left shoulder limited him to a .200 average with one home run and 9 RBIs in 78 official at-bats.62 In late May, Garvey learned that his shoulder would require surgery if he wished to prolong his career. Larry Bowa was managing the Padres at the time:

“On May 23 in San Diego,” as Bowa remembered, “Garvey took his last major league [at-bat], a ninth inning pinch-hit appearance against Montreal’s Neal Heaton. He flew out lazily to center field. A day later, Garvey began to prepare for surgery. There was not enough power left in the shoulder for him to make a comeback in 1988.”63 Steve’s final numbers consisted of 2,599 base hits with 440 doubles, 272 home runs, 1,308 RBIs, and a near-perfect .996 fielding percentage.64

On April 16, 1988, the Padres retired Garvey’s uniform number 6, the first San Diego player to be so honored. After his retirement, Steve founded Garvey Communications, a television production company, while lending his name to corporate products including Sport magazine and Fleer Skybox. He continued to serve the Multiple Sclerosis Foundation as its honorary chairman, and he also founded a counseling firm for retired athletes. Appearances in television, film, and documentaries continued in the 1990s and beyond. A gentleman of leisure, Garvey enjoyed golf and skiing. He has also worked in alumni relations for the Dodgers.

In January 1989, Garvey met the former Candace Thomas, a divorced mother of two, at a benefit for the Special Olympics. After a whirlwind courtship with stops at the presidential inauguration for George H.W. Bush and the Super Bowl, Candace became the new Mrs. Steve Garvey on February 18. Before the ink on their marriage license had even dried, their nuptials would soon be tested.

The spring of 1989 was an inopportune time to be a baseball superstar. After the sport was jolted by scandals involving Pete Rose and Wade Boggs, two women filed paternity suits against Garvey.65 For a player who went to great lengths to preserve a family-friendly image in Ronald Reagan’s America, the suits represented a precipitous fall from grace.

Although never a Steve Garvey fan, Dick Williams rushed to his defense. In the three years that he managed Garvey, Williams affirmed, “I never saw any of that. … I never saw him in bars” and “he seemed as clean as his image.”66 To his credit, Garvey never denied the charges, as evidenced by the candor of this 2003 interview:

“Could I have been more careful? Yes. Are they my responsibility? Yes. They were two personal choices, and if I had them to do over again, obviously I would do them differently. I made two poor choices, but it happened. I didn’t commit a felony, and I stood there and answered every question. I took responsibility. But what I did was out of character.”67

Like Gil Hodges before him, Garvey was a mainstay as a Dodgers first baseman for over a decade, but like his idol, Garvey continued to be bypassed for induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1986 he was considered one of the 10 active players most likely to be enshrined in the Hall.68 During his 15 years on the ballot, Garvey’s high-water mark was 43 percent of the vote, in 1995.69 Bruce Markusen, author of the “Cooperstown Confidential” column, offered the following explanation:

“Garvey’s Hall of Fame case has been hurt by SABRmetrics, which show him to be a weaker offensive player than originally thought. He never drew a lot of walks — and that worked against him. He was … more of a line drive hitter who hit a decent but not overwhelming number of home runs per season.” Markusen continued, “On the other hand, he spent a large majority of his career playing at Dodger Stadium, a ballpark that has suppressed offensive numbers for years.70

The call from Cooperstown notwithstanding, Garvey has been honored by the Michigan State University Athletics Hall of Fame in East Lansing and the Irish American Baseball Hall of Fame in New York. After many years in Utah, Steve and Candace returned to Southern California with their three children.

For a time, it seemed that if any player was destined to be a Los Angeles Dodger it was Steve Garvey. The former batboy broke in with his favorite team in 1969 and after switching positions from third base to first, became a model of consistency at the plate and on and off the field. The rise of his career was timed with an increasingly conservative undertone in America, and Garvey’s image made him an appropriate spokesman for the movement. No longer a “Dodger for life,” Garvey hung his star in San Diego in 1982 and brought instant credibility to the Padres franchise. The indiscretions that were revealed after his retirement did not negate the positives. Rather, they made him human. Whether Cooperstown finds him worthy of membership or not, Steve Garvey remains an important link in Dodgers lore between Koufax and Drysdale on one end and Fernandomania on the other.

Last revised: March 1, 2018

- Related link: Listen to Steve Garvey’s one-on-one oral history interview at the 2019 SABR convention in San Diego

This biography originally appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

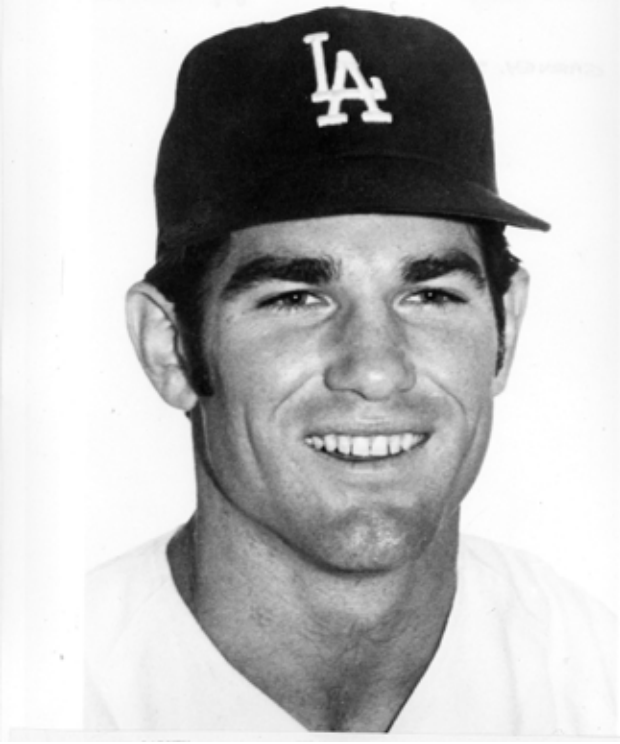

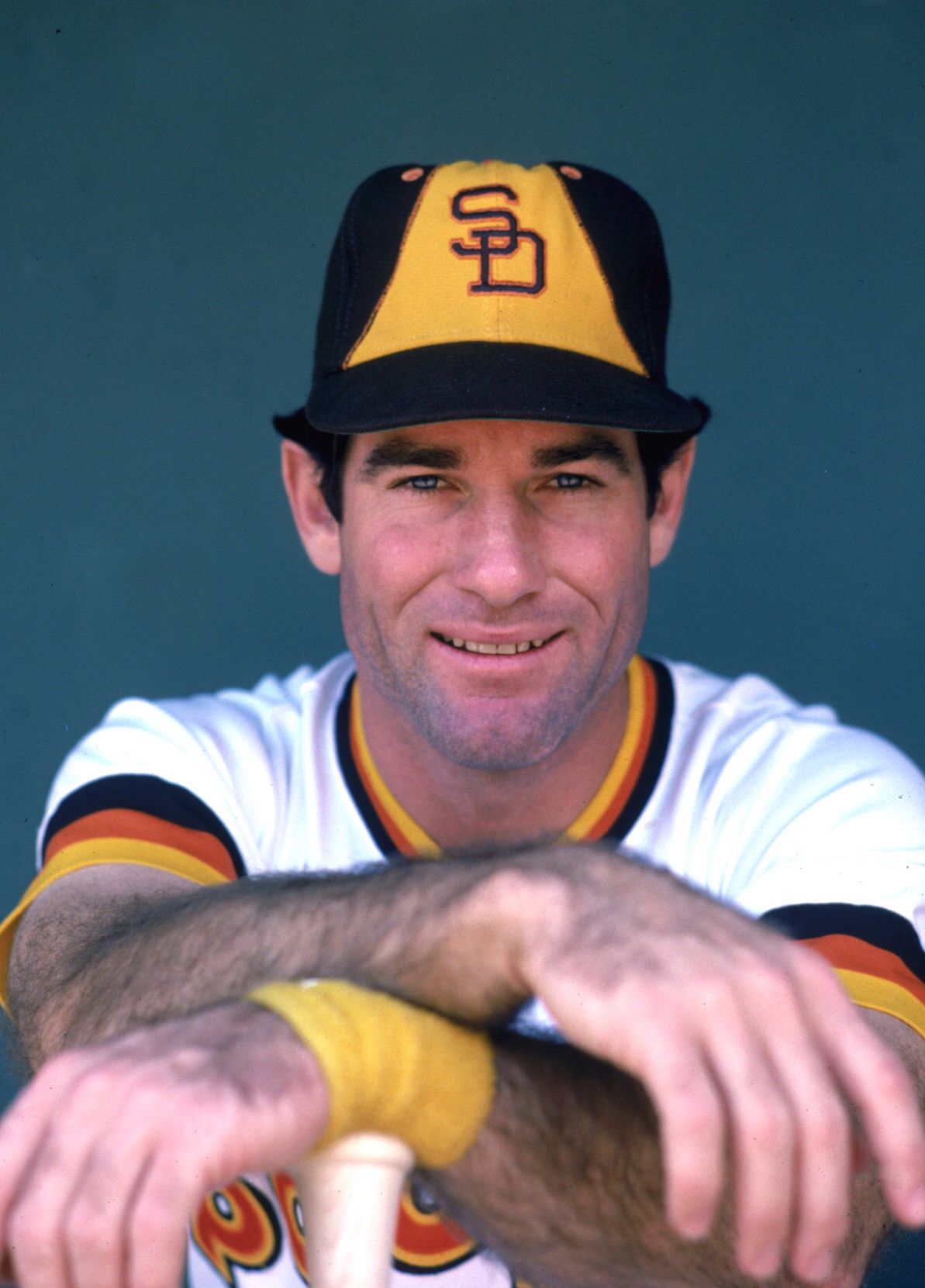

Photo Captions

Steve Garvey and his movie star looks made him a natural for appearances in theatrical films, television movies, and television series. Photos courtesy of the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Diego Padres.

Sources

The author would like to express his appreciation for assistance to Roland Andreassi (1933-2007), William Berman, Barry Bloom, Bill Buckner, Fred Claire, Chris Dean, Bill Deane, Dan Epstein, Michael Fallon, Colin Gunderson, Mrs. P.L. Hirsch, Mark Langill, Bruce Markusen, Wayne McBrayer, Dan Schlossberg, Bill Swank, and Alain Usereau.

Notes

1 Roy Blount Jr., “Born to Be a Dodger,” Sports Illustrated, April 7, 1975.

2 Mort Zachter, Gil Hodges: A Hall of Fame Life (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 157.

3 Steve Garvey and Skip Rozin, Garvey (New York: Times Books, 1986), 27.

4 Garvey, 34-35.

5 John Manuel, “The History and Future of the Amateur Draft,” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 39, Number 1 (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, Summer 2010), 66.

6 Garvey, 40.

7 retrosheet.org.

8 Garvey, 56.

9 Rob Neyer, Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Lineups (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 119.

10 Garvey 56-57. (Marshall had been a guest lecturer in one of Garvey’s courses at Michigan State University.)

11 Neyer, 115.

12Author interview with Bill Buckner, May 7, 2016.

13 retrosheet.org.

14 David Porter, ed., “Steve Garvey,” Biographical Dictionary of American Sports (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000), 540.

15 Garvey, 73-74.

16 Garvey, 74.

17 Michael Fallon, Dodgerland: Decadent Los Angeles and the 1977-78 Dodgers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 26. (Rico Carty was the first, in 1970.)

18 baseball-reference.com.

19 Garvey, 77.

20 Dan Epstein, Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging 1970s (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2010), 141.

21 Garvey, 81.

22 baseball-reference.com.

23 Lou Brock and Franz Schulze, Stealing Is My Game (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1976), 192.

24 Ibid.

25 Fallon, 145.

26 Porter, 541.

27 Garvey, 108.

28 William C. Berman, America’s Right Turn: From Nixon to Clinton, second edition (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 60-61.

29 Berman, 61.

30 Dominic Sandbrook, Mad As Hell: The Crisis of the 1970s and the Rise of the Populist Right (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), 323.

31 Rick Reilly, “America’s Sweetheart,” Sports Illustrated, November 8, 1989.

32 Zander Hollander, “Pete Rose,” The Complete Handbook of Baseball: 1978 Edition (Chicago: Signet Press, 1978), 177.

33 Fallon 149.

34 Betty Cuniberti, “Garvey: The Exception More Than the Rule,” San Bernardino County Sun, June 15, 1975: 54.

35 Garvey, 91.

36 Cynthia Garvey and Andy Meisler, The Secret Life of Cyndy Garvey (New York: St. Martin’s, 1989), 136.

37 Garvey, 100.

38 Fallon, 154-155.

39 Tom Boswell, “As Smith Goes, So Go Dodgers, 5-4 Win Over Phils,” Washington Post, August 16, 1978.

40 Milton Richman, “LA’s Garvey, Sutton Explode in Fist Fight,” Salina (Kansas) Journal, August 21, 1978: 9.

41 Epstein, 269.

42 Richman, 9.

43 Fallon, 331.

44 Garvey, 119.

45 Fallon, 321.

46 retrosheet.org.

47 Alain Usereau, The Expos in Their Prime: The Short-Lived Glory of Montreal’s Team, 1977-1984, English edition (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2013), 144.

48 baseball-reference.com.

49 Neyer, 121.

50 Garvey, 176.

51 Garvey, 183.

52 Bill Swank, Baseball in San Diego: From the Padres to Petco (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing Inc., 2004), 84.

53 Garvey 187.

54 Douglas B. Lyons, 100 Years of Who’s Who in Baseball (Guilford, Connecticut: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 121.

55 Garvey, 5.

56 Dick Williams and Bill Plaschke, No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Life of Hardball (Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990), 243.

57 Porter, 541.

58 Williams, 241.

59 Williams, 265.

60 Williams, 266.

61 Richard Gossage and Russ Pate, The Goose Is Loose (New York: Ballantine Books, 2000), 199.

62 Larry Bowa and Barry M. Bloom, I Still Hate to Lose (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing Inc., 2004), 90.

63 Bowa, 92.

64 Porter, 540-541.

65 Charles F. Faber and Zachariah Webb, The Hunt for Red October: Cincinnati in 1990 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2015), 75.

66 Williams, 243.

67 Bruce Schoenfeld, “Steve Garvey’s Public Exile” on Street & Smith’s Sports Business Daily Global Journal (March 3, 2003), sportsbusinessdaily.com, accessed December 7, 2016.

68 Zev Chafets, Cooperstown Confidential (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010), 69.

69 baseball-reference.com.

70 Author interview with Bruce Markusen, May 26, 2016.

Full Name

Steven Patrick Garvey

Born

December 22, 1948 at Tampa, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.