Jim Whitney

During the early 1880s, fireballer Jim Whitney ranked among baseball’s most accomplished pitchers, notching two seasons with 30-plus wins and pitching the Boston Beaneaters to the National League pennant in 1883. But afterwards, events conspired to undermine Whitney’s productivity. After the 1885 season, he was sold by Boston and thereafter consigned to labor for dismal, non-competitive teams. Then, an 1887 pitching rule change restricted his signature hopping windup and delivery. Most consequential of all was the onset of a chronic, ultimately life-ending disease. Less than 10 months after throwing his final major league pitch, “Grasshopper Jim” Whitney was dead at age 33, a victim of consumption (tuberculosis). A look back at his sadly brief life follows.

During the early 1880s, fireballer Jim Whitney ranked among baseball’s most accomplished pitchers, notching two seasons with 30-plus wins and pitching the Boston Beaneaters to the National League pennant in 1883. But afterwards, events conspired to undermine Whitney’s productivity. After the 1885 season, he was sold by Boston and thereafter consigned to labor for dismal, non-competitive teams. Then, an 1887 pitching rule change restricted his signature hopping windup and delivery. Most consequential of all was the onset of a chronic, ultimately life-ending disease. Less than 10 months after throwing his final major league pitch, “Grasshopper Jim” Whitney was dead at age 33, a victim of consumption (tuberculosis). A look back at his sadly brief life follows.

James Evans Whitney was born on November 10, 1857, in Conklin, New York, a Southern Tier village situated near the Pennsylvania border. He was the youngest of three children1 born to farmer Rufus Park Whitney (1830-1902) and his first wife Catherine (1832-1879), and a descendent of WASP homesteaders who had tilled the region’s soil for generations.2 When Jim was still a youngster, his father relocated the family to nearby Binghamton, where Jim completed a rudimentary education before beginning fulltime work on the Whitney farm.

Our subject began his ball-playing days as a teenager, following his brother Charlie (two years older) onto local sandlots. In 1878, Jim entered the professional ranks as left fielder for the short-lived Binghamton Crickets of the International Association. After Binghamton disbanded, he finished the season playing first base for an unaffiliated pro club based in Oswego, New York.3 The following year, he joined Charlie on the Omaha Green Stockings of the Northwestern League. Although signed as a second baseman, Jim often formed a battery with his brother, the Green Stockings’ principal pitcher.4 But in time, Jim – “regarded as the best batter and thrower in the club” – supplanted Charlie in the box and came “to the front as one of the most effective pitchers in the West.”5

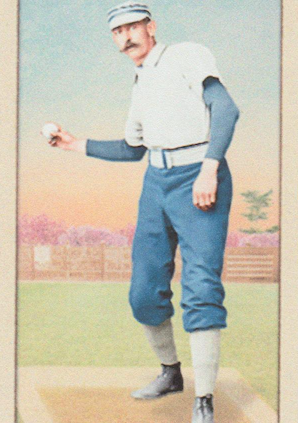

Jim Whitney presented a striking figure on the field. Tall and rangy (6-feet-2, 172 pounds), the right-hander towered over most enemy batsmen and unsettled many with a convoluted hopping windup, a rifle-shot fastball, and a penchant for pitching inside, there being no penalty at the time attached to hitting opposition batters.6 And like other hurlers at that time, Whitney benefited from lax enforcement of rule restrictions intended to prohibit over-the-top pitching motions such as his.7 A lefty batter with extra-base power, Whitney also helped himself with the stick. In fact, his batting average stood at a lofty .347 when the Northwestern League abandoned play in early July.8 After the NWL’s collapse, Jim and Charlie Whitney continued playing for Omaha in non-league contests, and then finished the season on the West Coast, joining a pro club in San Francisco.

The brothers returned West in 1880, where Jim dominated the California League. Pitching for the San Francisco Knickerbockers, Whitney led the circuit’s hurlers in victories (23), strikeouts (150), ERA (1.11), and winning percentage (.793)9 as the Knicks sailed to the league title. Over the ensuing winter, he attained major league status, signing for $1,050 with the Boston Red Stockings of the National League, a sixth-place (40-44-2, .476) finisher in final league standings.

On May 2, 1881, 23-year-old Jim Whitney made a successful major league debut, setting down the Providence Grays on six hits and winning, 4-2. The good-hitting Whitney also contributed three base hits to the Boston cause.10 Thereafter, manager Harry Wright kept handing him the ball, with Whitney starting 11 of the Red Stockings’ first dozen games. As the season continued, Wright continued to overwork the club’s new hurling stalwart, starting Whitney in 14 consecutive games (July 18 to August 11) and then 11 more in a row (August 17 to September 8).11 During these stretches, two career-long Whitney characteristics came to the fore. First, it became evident that catching the hard thrower was a difficult and punishing assignment for a minimally protected receiver. And as hard as Whitney was on catchers, he was even worse with umpires, “never for an instant stopping his kicking and demanding everything within a foot of the plate.”12

In the end, the workload took its toll and Whitney finished the season with a losing record (31-33, .484) for another sixth-place (38-45, .458) Boston club. But the sheer volume of his work produced National League-leading totals in no fewer than 10 pitching categories: victories,13 defeats,14 appearances (66), starts (63), complete games (57), innings pitched (552 1/3), base hits allowed (548), walks (90), wild pitches (46), and batters faced (2,301). On rare days off from pitching duty, Whitney played center field (15 games) or first base (two games), chipping in a .255 batting average (72-for-282), with 32 RBIs in 75 games, overall.

The following season, new Boston manager John Morrill used Whitney less profligately, giving ample work to veteran Bobby Mathews (19-15 in 34 games) as well. And toward the end of the campaign, 21-year-old newcomer Charlie Buffinton was worked into the rotation. But as in the year before, Jim Whitney was the Red Stockings’ pitching mainstay. In 49 appearances, he went 24-21 (.533), with a 2.64 ERA in 420 innings pitched. Whitney again led the National League in wild pitches (29), but this was likely a reflection of the problems that his lively fast ball and sharp-breaking curve presented to the Boston catching corps. In fact, Whitney had exceptional command of the strike zone, walking fewer than one batter (0.9) per nine innings pitched, and in the seasons to come he would regularly lead NL pitchers in strikeouts-to-walks ratio. Whitney also contributed a productive year with the bat, posting club highs in batting average (.323), on-base percentage (.382), slugging average (.510), and home runs (5). Meanwhile, the Red Stockings moved up to a tie for third in final NL standings (45-39-1, .536). They set their sights on a pennant in the coming season.

Despite the club’s improvement under manager Morrill, the Beaneaters (as the club had become known) began the 1883 season with a new field leader: second baseman Jack Burdock. An innovation adopted by the club’s new skipper was alternating Jim Whitney and Charlie Buffinton between center field and the pitcher’s box. Although neither was a particularly adept defensive outfielder (Whitney: .795 fielding percentage in 40 games; Buffinton: .756 in 51 games), both men were solid batters. More important, the hard-throwing Whitney and Buffinton, a breaking ball pitcher with an exceptional overhand drop, kept opposition lineups off balance and complemented each other nicely. But at first, the arrangement proved a disaster – particularly for Jim Whitney. He dropped his first three starts and seven of his initial eight decisions. Thereafter, both Whitney and the Boston club got back on track. Still, the Beaneaters were stuck in the middle of the NL pack when first baseman Morrill was restored to the helm in mid-July.

Under its returned leader, Boston surged toward the top until the pennant race likely turned on the outcome of a four-game mid-September series between the league-leading Chicago White Stockings (52-34) and second-place Boston (50-34). The Beaneaters grabbed the opener behind a three-hit, nine-strikeout effort by Whitney, 4-2. The following day, Jim pitched Boston into first place with a 3-2 victory. After Buffinton had solidified Boston’s ascendancy with an 11-2 laugher, Whitney completed the four-game sweep of the erstwhile league leaders, outdueling Chicago ace Larry Corcoran, 3-1.15 From there, Boston cruised to the title, finishing 63-35 (.643), four games better than Chicago (59-39, .602) in final NL standings.

While Buffinton (25-14, .641) had provided yeoman support, the linchpin of Boston’s triumph was the outstanding work of staff ace Whitney. Despite his dreary start, he went a career-best 37-21 (.638), with a 2.24 ERA in 514 innings pitched. He led NL pitchers in strikeouts (345) while registering a stunning 9.86-to-1 strikeouts-to-walks ratio. He had also been his customary solid self with the bat, posting a .281 average with 42 extra-base hits and 57 RBIs in a career-high 96 games, overall.

Apart from setting new personal high marks for victories and strikeouts, 1883 was a watershed season for Whitney in several other respects. Appearing in newsprint for the first time was the nickname by which our subject is known today: Grasshopper Jim.16 Modern authority posits various bases for the moniker. Nineteenth-century baseball scholar David Nemec attributes it to Whitney’s “elongated body and relatively small and narrow head,”17 while previous SABR biographer Harold Dellinger ascribes the nickname to Whitney’s “unusual gait.”18 But a more probable source may be Whitney’s frantic hopping windup and delivery, which one contemporary observer described as “doing a running high jump and a back handspring before sending the ball at the terrified batsman.”19

Another memorable line finding its way into newsprint that year described Whitney as having “a head the size of a wart with a forehead slanting at a 45-degree angle.”20 More than a century later, Bill James invoked this uncharitable jibe in designating Grasshopper Jim Whitney the “ugliest” ballplayer of the 1880s.21 With smallish cranium, weak chin, and receding hairline, Whitney’s looks fell something short of matinee idol. Yet contemporary club photos reveal Whitney to be a man of rather unremarkable appearance, and better looking than at least several Boston teammates.

In any case, Jim’s looks did not prevent him from landing a mate in late 1883. In time, marriage to New Hampshire-born Lillian Haddock yielded Whitney both a legacy (daughter Mollie) and financial security in the form of a prosperous commercial partnership with Lillian’s business-savvy brothers George and Edgar. From then on, the success of Whitney & Haddock, their Boston wholesale grain dealership, relieved Jim of the need to secure his livelihood entirely from baseball.

Reward for Whitney’s 1883 performance came in the form of a $2,500 contract for the new season. But hampered by both arm trouble and illness, he could not match his previous year’s numbers and relinquished the role of staff ace to Charlie Buffinton (48-16, .750). Nevertheless, Grasshopper Jim pitched well when available, throwing an 11-strikeout, one-hitter at the New York Giants in June and going 23-14 (.622), with a personal major league career-best 2.09 ERA in 336 innings pitched for the season. And his 270 strikeouts vs. just 27 walks translated into a phenomenal 10-to-1 ratio, easily the best in the National League. The pennant was lost, however, when Whitney had to be shut down over the final month of the season. Stopgap starters John Connor and Daisy Davis went a combined 2-7 in his stead and Boston finished a distant second 73-38-5 (.658) to the NL champion Providence Grays (84-28-2, .750).

The following season proved a disappointment to both Jim Whitney and the Boston Beaneaters. Like Charlie Buffinton (22-27, .449), Whitney posted a losing record (18-32, .360) in 1885. Although his 2.98 ERA in 441 1/3 innings pitched remained respectable, Whitney was hit hard, surrendering a league-worst 503 base hits and 146 earned runs, while also leading National League pitchers in defeats. The only positive mark on the Whitney ledger was his 200 strikeouts against 37 walks, a better-than-five-to-one ratio that again set the NL standard. At season’s end, Whitney was reserved by fifth-place (46-66-1, .411) Boston.22 However, his future with the club grew doubtful after the Beaneaters acquired Providence ace Hoss Radbourne early in the winter. The acquisition made Whitney expendable; on March 1, 1886, he and backstop Mert Hackett were sold to a new entry in the National League, the Kansas City Cowboys.

Pitching for a dismal (30-91-5, .248) Kansas City club, Whitney shared the misery of his 12-32, .273 log with Cowboys pitching partner Stump Weidman (12-36, .250), who replaced him as NL leader in pitching losses, hits surrendered, and earned runs allowed. For Whitney, likely the only bright spot in his year came during the postseason when an exhibition game against the Rochester Maroons of the International Association allowed him to square off against his brother Charlie, the Rochester second baseman.23

The financially failing Kansas City Cowboys disbanded over the winter, with the club roster placed under National League control. On March 9, 1887, Jim Whitney and two other former Cowboys were sold to the Washington Nationals.24 Once again toiling for a bad club, Whitney revived his career by registering a commendable 24-21 (.533) record for a seventh-place club that otherwise went 22-55 (.286). And he accomplished this notwithstanding the adoption of a new pitching rule that curtailed employment of his trademark hopping delivery. Now, pitchers were required to keep their back foot anchored to the rear line of the pitcher’s box on deliveries toward home plate. Having to adapt his motion to the rule restriction, Grasshopper Jim was no longer the power pitcher of his early years. Nevertheless, he posted another NL-leading differential in strikeouts (146) to walks (42), while batting a useful .264 between pitching assignments and occasional outfield duty.

The following spring, Whitney was appointed Washington team captain.25 Sober, serious, and somewhat aloof, he was not a favorite of teammates or the press. But he was widely respected, particularly for his probity. While a member of the Boston, Kansas City, and Washington ball clubs, Whitney was thrice selected to act as game arbiter by opposing team captains when the NL-assigned umpire failed to appear. The issue, therefore, was not his fitness for the Nationals’ leadership post, but his fitness, period, as concern for his well-being had become widespread. Even before his appointment, Whitney was fending off reports of ill health, maintaining that he was “in excellent shape,” but then adding, curiously, that “all the rheumatic cure that I ordered was for my friends.”26

Early in the 1888 season, a line drive by Pittsburgh Alleghenys batsman Bill Kuehne struck Whitney hard in the right chest, forcing him to retire from the game.27 Later generations of the Whitney family traced the onset of Jim’s fatal illness to being struck by the Kuehne liner.28 Yet even before that fateful event, reports had circulated that Jim Whitney was suffering from consumption.29 Other reports had him stricken with pleurisy. Whatever the actual case, Whitney was not the same pitcher that he had been the year before. Nevertheless, he managed 39 starts for a lousy last-place (48-86-2, .358) Washington club, and his 18-21 (.462) record was well above the club norm. Late in the season, moreover, his Washington stay united Jim with young brother-in-law and pitching protégé George Haddock. But Haddock was still three seasons away from his 34-win breakout campaign of 1891, and the Whitney-Haddock combo was a brief one.30 Meanwhile, back on the health front, that December it was reported that “Jim Whitney has entirely recovered from the severe cold which clung so tenaciously for several months last season and hopes to be in winning form when the season opens.”31

Before the season started, Whitney’s primary concern was not his health but his paycheck. A vocal critic of the salary classification scheme adopted by National League club owners that winter, Whitney resented his relegation to Class B remuneration, with top-level salaries being restricted to John Clarkson, Hoss Radbourne, Tim Keefe, Mickey Welch, Pud Galvin, and a few other pitchers.32 Whitney was also angered that the Washington club had cited his health problems as reason for a salary cut. “Last year I was unfortunately ill, and they want to bring this up against me to operate as a reduction in salary,” Jim complained.33 Proud and financially secure, Whitney refused Washington’s $2,500 salary offer, seeking $3,000.34 Still, the classification scheme allowed the club no leeway on Whitney’s stipend, even if it were disposed to offer him a higher wage.35 The parties therefore remained at loggerheads until near the 1889 season’s start. Then, Washington traded Whitney to the Indianapolis Hoosiers for pitcher Egyptian Healy.36

Unhappily for Grasshopper Jim, the move to Indianapolis consigned him to another bad team. This time, however, Whitney was no better, indeed somewhat worse, than his seventh-place (59-75, .440) ball club. In nine appearances, he was hammered for 106 base hits in only 70 innings pitched, and went 2-7 (.222) with an unsightly 6.81 ERA. Along the way, an 8-6 defeat by the New York Giants on May 29 afforded Whitney the unwanted distinction of becoming the second major league pitcher to register 200 losses.37

Released by Indianapolis in late June but intent upon continuing his career,38 Whitney returned to the minors for the first time in a decade, signing with the Buffalo Bisons of the International Association.39 As a member of yet another club headed for a seventh-place (41-65, .387) finish, he managed to eke out a respectable 11-11 mark despite being tagged for 244 base hits in 197 innings. More important than his numbers was the fact that, with major league expansion in the form of the rebel Players League on the horizon, Whitney had resurrected his chances of another shot at pitching at the game’s highest echelon.

Whitney remained on the sidelines as the 1890 season began but was eventually signed by the Philadelphia Athletics of the major league American Association. He was shaky in the first three innings of his June 17 audition against the Brooklyn Gladiators; but then settled down to post a 5-2 victory.40 But it soon became obvious that he had little left. In a losing July 16 outing against the St. Louis Browns, Whitney surrendered a staggering 23 base hits.41 Days later, Philadelphia released him, bringing Whitney’s 10-season major league career to a close.

With the second half of his major league tenure hamstrung by illness, rule changes, and pitching for non-competitive ball clubs, Grasshopper Jim Whitney finished with a sub-.500 career record. In 413 pitching appearances, he went 191-204 (.484), with a 2.97 ERA in 3,496 1/3 innings pitched. Although he had three 30-loss seasons, the ample positive marks of his tenure in the big leagues included leading National League hurlers in victories (1881), innings pitched (1881), and strikeouts (1883). And he won 37 games for Boston’s pennant-winning club of 1883, and threw 26 career shutouts. Whitney had also been something of a pitching rarity: a flamethrower with exceptional command of the strike zone. On five separate occasions, he walked fewer batters per nine innings pitched than any other NL hurler. And four times he led league pitchers in strikeout-to-walk ratio, including the phenomenal 10-to-1 mark posted in 1884. The lefty-swinging Whitney had also been a force with the bat, hitting a respectable .261, with 170 extra-base hits and 280 RBIs in 550 games played, overall.

Following his release, Whitney returned to Boston to tend to his business interests. But despite his affluence, separation from the game weighed heavily on his mind. Indeed, it was publicly reported that friends feared that the depressed Whitney might commit suicide.42 “Jim is all right so far as money is concerned … but it breaks him up that he cannot pitch as he could in days gone by,” a friend advised the press, grimly. “He is almost despondent about it, and I wouldn’t be a bit surprised to hear some day that he had gone over Niagara Falls in a bat bag.”43

Over the winter, Whitney’s spirits recovered. But his health rapidly and irreversibly deteriorated, and, ultimately, he decided to go back home to die. On May 21, 1891, James Evans “Grasshopper Jim” Whitney died in Binghamton from complications of tuberculosis. He was 33. Private funeral services were followed by interment at Spring Forest Cemetery, Binghamton. A quarter-century after his passing, old foe Jim O’Rourke remembered the deceased respectfully: “Jim Whitney … would let the ball go with terrific speed. It was a wonder that anyone was able to hit him at all. He was the swiftest pitcher I ever saw.”44

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Sources

Sources for the biographical data imparted above include the Jim Whitney file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the Jim Whitney profiles published in Major League Player Profiles, Vol. 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); Harold Dellinger, Nineteenth Century Stars, Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker, eds. (Cleveland: SABR, 1989); and the New York Clipper, September 23, 1882; US and New York State Census and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Jim’s older siblings were sister Alice (born 1853) and brother Charles (1855).

2 Our subject’s great-grandfather Joshua Whitney was reputed to be the first white settler of Binghamton, New York, per sports editor John Fox, Binghamton Sunday Press, July 2, 1967.

3 Per the James E. Whitney profile published in the New York Clipper, September 23, 1882.

4 Omaha’s signing of C.E. Whitney, pitcher, and J.E. Whitney, second baseman, was noted in “The National Game,” Omaha Bee, March 25, 1879: 4, and “The National Game,” Omaha Herald, March 23, 1879: 5.

5 Per “Base Ball,” Omaha Bee, July 5, 1879: 4.

6 The rule awarding first base to a batsman hit by a pitch was not implemented until the 1887 season.

7 Arm angle restrictions were not officially jettisoned until after the 1883 season, but penalties for overhand pitching were rarely, if ever, imposed during the preceding seasons, with technically forbidden pitching motions like Whitney’s becoming commonly employed.

8 Per the Jim Whitney profile by Harold Dellinger in Nineteenth Century Stars, Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker, eds. (Cleveland: SABR, 1989), 138.

9 Per 1880 California League stats published in The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 3d ed., 2007), 135.

10 Per the box score published in the Boston Globe, May 3, 1881: 2.

11 As indicated by Retrosheet’s game-by-game log for the 1881 Boston Red Stockings.

12 As subsequently reported in “League Pitchers,” Sporting Life, December 22, 1886: 1, which added that “when at the bat, [Whitney] is the same as in the box” when it came to argumentative behavior.

13 Whitney tied for NL lead in victories with Larry Corcoran (31-14, .689) of the Chicago White Stockings.

14 Only one pitcher has replicated Whitney’s feat of leading a major league in both wins and losses in the same season: Phil Niekro (21-20) for the 1979 Atlanta Braves.

15 A more detailed recap of the crucial series is provided by Mark Pestana on the Games Project website. See “September 10-13, 1883: Grasshopper Jim Whitney Snatches Pennant,” originally published in Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the Nineteenth Century, Bill Felber, ed. (Phoenix: SABR, 2013), 152-155.

16 The first mention of the Grasshopper nickname discovered by the writer appeared in “Sporting Gossip,” Cleveland Leader, May 16, 1883: 3. Within a year thereafter, use of the new Whitney nickname became widespread.

17 Per the Jim Whitney profile in Major League Player Profiles, Vol. 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 198.

18 See the Jim Whitney profile in Nineteenth Century Stars, 138.

19 “But Few Old-Timers Left,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Globe, June 5, 1891: 2.

20 Detroit Evening News, August 10, 1883.

21 The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2000), 41.

22 Per “The Reserves,” Sporting Life, October 28, 1885: 1.

23 As reported in “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1886: 5. Charlie Whitney played minor league ball through the 1889 season but never reached the big leagues.

24 As reported in “Dickering with Kansas City,” Sporting Life, March 16, 1887: 1. Also sold to Washington were former KC infielders Al Myers and Jim Donnelly.

25 See “Whitney Team Captain,” (Washington, DC) Critic, April 14, 1888: 8.

26 “Pittsburg Pencillings,” Sporting Life, February 29, 1888: 2.

27 See “Washington Plays Well,” (Washington, DC) National Republican, May 20, 1888: 1.

28 As reflected in a letter from granddaughter F. Whitney Jaeger to Hall of Fame historian Cliff Kachline, dated November 18, 1977. It is the writer’s understanding that chest trauma is a rare but conceivable cause of consumption (tuberculosis). But the etiology of Jim Whitney’s illness is unknown.

29 See e.g., “Baseball Smalltalk,” Critic, May 14, 1888: 4.

30 Haddock went 0-2 in a late-season try-out with Washington and struggled to find a major league foothold until he posted a scintillating 34-11 record for the 1891 American Association Boston Reds. By that time, sadly, brother-in-law and pitching mentor Jim Whitney was dead.

31 “Washington Whispers,” Sporting Life, December 5, 1888: 3.

32 Per “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, February 6, 1889: 5. See also, “Jim Whitney’s Appeal,” Boston Globe, February 6, 1889: 1.

33 “Hub Happenings,” above.

34 See “Sowders May Be Transferred,” Saint Paul Globe, March 10, 1889: 8.

35 As reported in “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, February 20, 1889: 2, citing the Boston Herald.

36 As reported in “The Deal Consummated,” Detroit Free Press, March 30, 1889: 8; “Traded Whitney for Healy,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, March 30, 1889: 5; and elsewhere.

37 Two seasons earlier, Pud Galvin had become the first major league hurler to lose 200 games.

38 Per “Indianapolis Mention,” Sporting Life, June 26, 1889: 8.

39 As reported in “Whitney Comes Here,” Buffalo Times, July 3, 1889: 2; “On the Diamond,” Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, July 2, 1889: 3; and elsewhere.

40 See “Jim Whitney Pitched,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 18, 1890: 3.

41 See game account/box score in “American Association,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 17, 1890: 3.

42 See e.g., “Singles,” Chicago Inter Ocean, September 16, 1890: 3; “Sporting Notes,” Detroit News, September 13, 1890: 1.

43 “Notes of the Diamond Field,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 10, 1890: 3.

44 Thomas F. Magner, “Jim O’Rourke’s Wonderful Diamond Career,” Sporting Life, December 4, 1915: 10.

Full Name

James Evans Whitney

Born

November 10, 1857 at Conklin, NY (USA)

Died

May 21, 1891 at Binghamton, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.