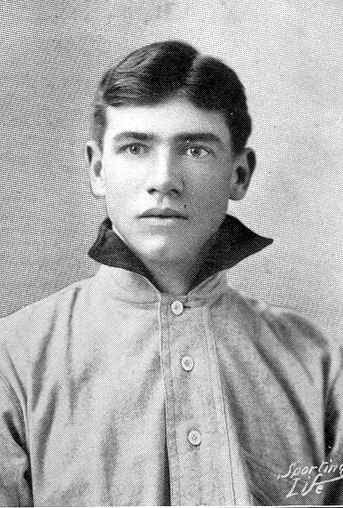

Jimmy Sebring

Jimmy Sebring was one of those players who surface ever year or so that are identified as “can’t miss” candidates for major league baseball stardom. Big for his time at 6 feet, 180 pounds, Jim had it all when it came to baseball: instincts, a strong and accurate throwing arm, speed, and a natural hitting ability from the left side. A correspondent for Sporting Life noted after only month of watching Sebring he was “a better man” than either Bill Lange or Hans Wagner, two of the biggest stars in the National League. Despite his natural talent and early success, Jimmy’s temperament and an illness brought his major league career to a premature and tragic end.

Jimmy Sebring was one of those players who surface ever year or so that are identified as “can’t miss” candidates for major league baseball stardom. Big for his time at 6 feet, 180 pounds, Jim had it all when it came to baseball: instincts, a strong and accurate throwing arm, speed, and a natural hitting ability from the left side. A correspondent for Sporting Life noted after only month of watching Sebring he was “a better man” than either Bill Lange or Hans Wagner, two of the biggest stars in the National League. Despite his natural talent and early success, Jimmy’s temperament and an illness brought his major league career to a premature and tragic end.

James Dennison Sebring was born on March 22, 1882, in the tiny north central Pennsylvania borough of Liberty. John Sebring was a stone merchant whose youngest son James began working as a stone cutter while in his teens. Jimmy was exposed to a burgeoning baseball environment when his family moved to the nearby city of Williamsport. In a retrospective of Sebring’s baseball career in 1909 the Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin noted that in the latter 1890s Joe Mertz, manager of a semi-professional team, discovered an overgrown boy named Sebring playing baseball on the back lots of the city. The columnist also called to mind the day when, “playing in a suit that did not fit him and shoes entirely too big, Jimmy took off the shoes and finished the game in his stocking feet.” Sebring could hit but as a third baseman he was lacking. When Jimmy was moved to the outfield the youngster found his niche.

A contemporary source maintained that Sebring began playing semi-pro ball in 1898 with an independent team in Sinnamahoning, Pennsylvania. He also played with teams in Altoona and Williamsport, often a teammate of his good friend Fredrick “Bucky” Veil. The pair went to school at Bucknell University where they became members of the same baseball nine as Christy Mathewson. Following the 1901 college season, Jimmy joined a team in Wilmington, North Carolina, (Virginia-North Carolina League) where he made his mainstream professional debut, and a year later caught on with the Worcester, Massachusetts, club that had sent first baseman Kitty Bransfield to the Pittsburgh Pirates the previous spring.

Sebring got his big break when he replaced outfielder Jack Sharrott (an ex-New York Giant and Philadelphia Phillie) who was forced out of the Worchester lineup due to an eye problem. Sporting Life’s John R. Robinson wrote of the Hustlers’ newest recruit: “The real find of the outfield is James Sebring the old Bucknell player,” he wrote. “Judging from the work displayed by the newcomer, the management will not remove him from the game to allow Sharrott to play, as Sebring is one of the greatest all-around outfielders in the Eastern League.” Sebring accumulated 136 hits and batted .327 in 103 games for Worcester. At the conclusion of the Eastern League season Barney Dreyfuss, owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, purchased the Hustlers’ exciting young outfielder with the stipulation that if Sebring was retained the payment would be doubled.

On Monday, September 8, 1902, James Sebring made his initial appearance in Pittsburgh’s right field slot unsatisfactorily filled since Lefty Davis was disabled with a broken ankle at midseason. Fred Clarke was away from the club the day of Jimmy’s debut, and Honus Wagner was serving as acting manager. Sebring made his first major league hit off Joe McGinnity of the New York Giants in the first game of the double-header that day and in the seventh inning of the second game Jimmy’s single drove in two runners. However, the Pirates lost both contests. Ten days later, Jim made three hits, one a triple, and scored two runs in Pittsburgh’s ten-inning victory over St. Louis. After only a handful of games, Sebring had served notice he was in the majors to stay. Dreyfuss was excited about his new find and said ‘Jeems’ is “as good as they make them in the rough.”

The twenty-year-old outfielder made the best of his opportunity in the big leagues, batting .325 in 19 games with the Pirates. However, Frank Dwyer, manager of the American League’s Detroit club, chimed in that a month earlier he had signed Sebring to a contract to play for the Tigers in 1903. Jimmy confirmed that he had received $100 in advance money from Dwyer, but maintained that he had not signed the Tigers’ contract as the Detroit club claimed. While Sebring was awaiting the decision whether his baseball future would be in Detroit or Pittsburgh, his father died at age fifty-two that November.

When the two major leagues met to resolve their war in January 1903, a sticking point in the negotiations was how to distribute players whose contracts were in dispute. The debate became so contentious the magnates adjourned for the day. After talks resumed, the Cincinnati club agreed to withdraw its claim for outfielder Sam Crawford as a gesture of peace. When Barney Dreyfuss offered to give up Sebring, American League President Ban Johnson accepted the olive branch and reciprocated by renouncing Detroit’s claim on Sebring.

Sebring hit .441 in the Pirates’ exhibition games the following spring, living up to the form predicted by President Dreyfuss. Jimmy ingratiated himself with the Pittsburgh fans in the second home game of the 1903 season when he hit two home runs to the deepest parts of center field and the Buccaneers defeated the Cardinals, 8 to 4. In the second inning he batted a ball so squarely that it rolled beyond the pennant flagstaff in deep center field. “The people were surprised but Sebring’s sprinting made them open their eyes even still wider,” a local newspaper reported. “He started off like a whirlwind and made the circuit of bases in record time…” In the top of the fifth, St. Louis threatened to score when Homer Smoot attempted to go from first to third on a single into right field. Jimmy took the ball on one hop and fired a strike to Wee Tommy Leach at third base to retire a better than average runner in center fielder Smoot. In the home half of fifth inning Sebring sent a pitch on a long flight that was only interrupted by the middle field fence. When Jimmy reached home plate after duplicating his earlier exhibition of swift base running, the crowd went wild, and every one of the Pirates eagerly congratulated the Pirates newest star. “Sebring won the people of Pittsburgh,” pronounced the Pittsburg Press. “He was a hero yesterday. Every time he left the bench to go to the field he was loudly applauded. And yet he did not seem to mind the praise.”

Sebring had played in only seven regular season games, batting .310, when he was sidelined with an illness that confined him to bed. The Pittsburg Press reported on April 27 that Sebring was “really ill” and would be sent home to Williamsport. While Jimmy was disabled with an affliction described as “typhoid or brain fever,” Wagner played right field until Sebring returned to the lineup on May 12. At mid-season Jimmy was given three days off during a road trip to Chicago in order to travel to Williamsport on a special mission. On July 22 at five p.m., Jimmy was married to nineteen-year-old Elizabeth Milnor, eldest daughter of the county sheriff. Among the wedding gifts was a check for $350 from President Dreyfuss and a solid silver dinner set from the members of the Pittsburgh team. Jimmy’s batting average tailed off in 1903 to .277 for the 124 regular season games in which he played. The Pirates won the National League pennant for the third consecutive year and would play the Boston American League club in the very first World Series.

In the seventh inning of the first game in Boston, Sebring reached the game’s most renowned pitcher, Cy Young, for a long hit that soared over the right fielder’s head. Assuming the ball would go into the overflow crowd that was allowed to stand behind ropes in the outfield for a ground rule triple, Boston’s Buck Freeman casually pursued the ball. By the time the ball stopped rolling some ten feet from the ropes, the Pirate base runner was already turning third. The Boston center fielder ran over and retrieved the ball, but by the time the relay made it to the catcher, Sebring had crossed home plate to become forever known as the player who hit the first home run in World Series history. The Pirates lost the Series five games to three, but Jimmy easily led all players from both teams in batting with 11 hits in 31 at bats for a .367 mark; and he batted in seven of his team’s 21 runs scored. The next best mark on the Pirates was Tommy Leach’s .273. The Pirates each pocketed a $1,316 share when owner Dreyfuss pitched in the club’s share.

As was his practice, Dreyfuss made the players’ World Series checks out in the name of their wives. Barney tried to counsel Sebring in financial matters, but the player he called “Jeems” just couldn’t manage his money. During spring training at Hot Springs Sebring touched the club boss for $50 on account. Within an hour he spent the entire amount on cheap souvenirs. After Jimmy’s daughter Mary was born shortly after the start of the 1904 season, Dreyfuss put $400 of her father’s salary in the bank to the credit of the baby girl. However, Sebring was so persistent the Pirates’ boss finally allowed James to draw it all out.

An indication of Sebring’s discontent with the Pirates was reported by Sporting Life in May 1904. Jimmy claimed he was not in love with baseball and suggested he would go into another business when financially able. Jimmy’s dissatisfaction with the club was manifest in an incident during the team’s first series of the baseball season in St. Louis. After Bucky Veil whipped Tommy Leach in a fist fight at the team’s hotel, a rift developed among the players. Sebring unequivocally supported his friend Veil which garnered animosity from some of his teammates. Jimmy was further angered when Veil was released by the Pirates only two weeks into the season.

That summer, Honus Wagner took charge of the team in an excursion to Youngstown for an exhibition game after which he excoriated Sebring for his lethargic play in the Pirates embarrassing loss. The feud between Sebring and the team’s most important player reached a climax during a particularly bad performance by the Pirates against St. Louis on July 26. Early in the game, Wagner yelled at his right fielder when Jimmy was slow in fielding a single on which a Cardinal runner scored. Later, Sebring got his revenge after Honus erred on a throw from right field that allowed a runner to take an extra base. At the bench between innings, the pair continued their quarrel and Wagner reportedly took an errant swing at Jimmy. Upon learning of the tiff, Owner Dreyfuss summoned Sebring and spent an hour closeted with the player. Following the meeting, the club referred to Jimmy’s altercation with Wagner as a “little run-in” that was now fixed up, and Dreyfuss reportedly spoke to Jeems about some sort of deal to financially benefit his young player. However, Barney’s bond of friendship with the player was strained.

Sebring was unable to play ball after he suffered a badly sprained ankle in the first inning of a game with Cincinnati on July 31. Two days later when the team was to embark on an Eastern road trip, Jimmy showed up at Union Station walking with the aid of a cane. When Sebring was handed his sleeper car upper berth ticket by President Dreyfuss, the injured outfielder told his boss he was not able to travel to New York. Dreyfuss became upset with his employee’s attitude and informed Sebring he “could quit the team.” Instead of boarding the team’s train, Jimmy went home and was immediately suspended. The club’s position was that Sebring was examined by a well known doctor in Cincinnati who was an acquaintance of owner Dreyfuss. The outfielder was diagnosed as having a “turned ankle” and a treatment of cold water and ice packs was prescribed. According to the club, Sebring ignored the doctor’s advice and played cards much of that evening. After the incident at the train station Barney decided to rid his team of Sebring. The owner told reporters that he did not want to see the player or even hear his name again.

When he arrived home in Williamsport, Jimmy told a local newspaper reporter that the doctor had wanted to put his leg in a cast, but the outfielder would not allow it because he was supposed to go on the road trip with the Pirates. Sebring did not explain why he refused the cast then reported to the train station where he refused to make the trip. Jimmy did intimate that if the Pirates wanted him back they would have to contact him.

Pirates fans were stunned on August 11 when they learned that Sebring was traded to the Cincinnati Reds for outfielder Harry McCormick. Jimmy joined the Reds in New York and played right field in both games of a double-header on August 12. Fifteen days later, Sebring stepped in a hole chasing a fly ball and reinjured the ankle he hurt while with the Pirates.

Upon his return to Pittsburgh for the first time since the trade Sebring received quite an ovation from the “good sized” crowd when he stepped to the plate. “The young star has a host of friends in Pittsburgh most of whom were decidedly sorry to learn he had left the champs when that sensation occurred,” wrote Ralph Davis. Rain drops were descending from the clouds when Sebring came to bat in the first inning determined to make an impression on his former fans. Jimmy swung hard at a pitch from Patsy Flaherty, but all he could manage was a pop foul fly to third baseman Leach. The players immediately went into the clubhouse and after thirty minutes the game was called.

Jimmy didn’t make much of an impression on the Cincinnati fans in 1904, batting .225 with only eleven extra base hits in 56 games. When Sebring made a plea for his release that fall, the Cincinnati management gave him a $600 boost in salary to stay with the Reds. Jimmy experienced perhaps his best game as a Red on April 21, 1905, at Chicago’s West Side Grounds. He singled twice, doubled and tripled. In the field, he made a fine running catch and threw a man out at home. On the other hand, he also muffed a puny fly. Two weeks later Sebring left the Cincinnati team because his wife Elizabeth was ill with peritonitis. Though he declared his intention to accept a position with the Williamsport team of the outlaw Tri-State League, Jimmy relented and chose to return to the Cincinnati club. Upon his return to the lineup Sebring was applauded by the home fans each time he came to bat, but six weeks into the season, Jim was called home because Elizabeth’s health had taken a turn for the worse. August Herrmann loaned Jimmy money to pay his wife’s medical bills and the club owner told Sebring that if he stayed with the team until fall the loan would be considered a gift.

Before Jimmy left for the bedside of his unconscious wife, Ren Mulford Jr. of the Cincinnati Post noted, “There were tears in his eyes when Sebring bade Reds’ President Garry Herrmann good-bye with the promise to return as soon as he possibly could.”

Elizabeth Sebring’s surgery was a success, and Jimmy decided to play with the Williamsport club in order to remain close to her bedside. He notified the Reds’ management of his decision and requested permission to play with the local outlaw team for the remainder of the season.

The Williamsport club, known as the “Millionaires” or “Billies” was a member of the Tri-State League, composed mostly of Pennsylvania teams. Because these clubs played outside the National Agreement they were considered “outlaws.” Baseball’s National Commission, made up of the presidents of the American and National Leagues plus a chairman, Sebring’s employer Garry Herrmann, declared contract jumpers and players who ignored Organized Baseball’s reserve clause “forever” ineligible (black listed) unless the commissioners saw fit to reinstate them.

The Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin credited Sebring for the Billies’ sudden success in 1905. “Despite the efforts of Manager Lindehelmer and Captain Weigand the (Williamsport) players had become rather listless when Jimmy Sebring was secured to play the outfield and he infused into the other members of the team a considerable amount of ginger which he himself displayed. Following his lead the team began to bat and became conspicuous for its team work and this, with the excellent pitchers it had, made Williamsport a pennant winner.” For the 46 games in which Jimmy played for the Billies, he batted .329 (the highest average on the team) smacked six home runs and stole 25 bases.

The Reds grew tired of dealing with Sebring and that October traded the wayward outfielder and Harry Steinfeldt to the Chicago Cubs for pitcher Jake Weimer. However, Jimmy was perfectly content in Williamsport, and the deal had to be restructured. According to Ban Johnson, Sebring was on the National Commission’s blacklist for contract-jumping and was ineligible to play in “organized ball” anyway. However, Chairman Herrmann indicated that Sebring was not blacklisted, having gone to Williamsport with the Reds’ consent.

A few days after Cincinnati attempted to trade Sebring, Jimmy was elected manager and captain of the defending Tri-State champions for the 1906 season, replacing Max Lindheimer. On the other hand, W. A. Phelon, of Sporting Life, reported that Cubs owner Charles Murphy had traveled to Williamsport and was convinced Sebring would play for the Cubs. However, Jimmy never played an inning of ball with the Cubs, for when it came time to think about spring training, he was delving in a bit of mischief attempting to convince members of Organized Baseball to sign on with his outlaw team in Williamsport. Among his converts were third baseman Harry Wolverton, who had been unable to come to terms with the Boston Nationals, Outfielder Tom Delahanty who jumped the Pueblo Western League club, and Harry Gleason, third baseman for the St. Louis Browns the previous year.

In 1906 Jimmy Sebring managed a Williamsport team that “gathered together the greatest bunch of ball tossers that ever wore the Tri-State uniform.” Despite missing a substantial number of games due to injuries, Jimmy had not slowed up much from his days with the Pirates and collected twelve triples, hit eight home runs and stole 28 bases in the 100 games he played for Williamsport. However, there were morale issues on the club in addition to key players’ injuries. During the season, Sebring “became morose and suspicious,” reported the Washington Post. “He accused his closest friends on the team of undermining him and it was only the determined efforts of Joe Delehanty and Wolverton that prevented a complete mutiny.” Despite problems with their manager, Williamsport missed winning the Tri-State championship by only three games. Following the season, Sebring launched an effort to be reinstated by the National Base Ball Commission.

The Tri-State League would be absorbed by Organized Baseball in 1907, though not all of its blacklisted players were guaranteed automatic reinstatement into Organized Baseball. Sebring hoped he would be able to return to the major leagues and attended the National Commission’s annual meeting in Cincinnati that January. The Cubs held the major league rights to the player and President Murphy testified that he had authorized Sebring to stay at home in 1906 because his wife was close to death. The commissioners had several questions for Jimmy concerning the desertions from two major league clubs and other rules violations. Sebring acted as his own counsel and attempted to explain his misdeeds, but hurt his case when he said Manager Kelley allowed him to leave the Reds to go home at a time Joe Kelley wasn’t even with the team. However, the most damning charge against Sebring was the accusation that he had negotiated with major league players in attempts to recruit them for the Tri-State league. Jimmy denied the charges at first, but finally acknowledged that he had spoken over the phone with Howie Camnitz and a player with the Toledo club. He also admitted he sent wires to Togie Pittinger and Kitty Bransfield of the Phillies, but only after he read in the newspaper of their release. Not surprisingly, the National Commissioners rejected Sebring’s application for reinstatement. Jimmy had no recourse but to return to the Williamsport team and he signed a contract to play the 1907 season with the Billies.

Because Jimmy expected to be reinstated by the National Commission, he had supported Wolverton for manager of the Billies following the 1906 season. Williamsport won the Tri-State championship in 1907 but Sebring was long gone before the cup was clinched. Perhaps due to concerns about his wife, the rejection of his reinstatement request, and the fact he was no longer the manager but just another player caused a decline in Jimmy’s performance on the field. Manager Wolverton decided that Sebring had become a detriment to the team and sold Jimmy to Wilmington at mid-season.

The National Commission once again denied the appeal of Sebring for reinstatement in March 1908 so he started the season with Wilmington. Jimmy split a couple of months playing with Wilmington then Harrisburg. In only 47 games with the two Tri-State clubs, he batted .235, and only eight of his forty hits went for extra bases. That May Sebring was suspended for a week by the Harrisburg manager, and on June 20, 1908, he was suspended indefinitely. The Senators’ George Heckert was quoted as saying that so long as he was manager Sebring would not be playing with Harrisburg. A month later Jimmy hooked up with the Annville (Pa.) club, a “county league” team. So far had the batting star of the 1903 World Series fallen in less than five years.

Sebring visited Cincinnati that August to make yet another appeal to the National Commission chairman for his reinstatement. This time he brought along Mrs. Sebring and little Mary for support. Following a meeting with President Herrmann in which he professed remorse for his past missteps, Jimmy returned home to Williamsport.

Despite the obvious drop-off in his baseball skills there were still major league clubs that were interested in Sebring. Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbetts had coveted Jimmy when he played with Pittsburgh and maneuvered to acquire the outfielder. Despite reports from the Tri-State League detailing the player’s decline, Ebbetts traded a pitching recruit to the Cubs for the rights to sign the twenty-six-year-old outfielder to a contract if and when reinstatement was forthcoming.

During their meeting the following January, the National Base Ball Commission approved the reinstatement of James Sebring into Organized Baseball. There was a catch. Jimmy was required to pay a fine of $200 outright and the club that signed him to a contract would have to pay the Cincinnati Reds $600 Sebring owed Herrmann on the loan for Mrs. Sebring’s medical expenses. Jimmy went to spring training with the Superbas and opened the 1909 season as Brooklyn’s center fielder and clean-up hitter. Unfortunately, Sebring’s return was a failure as he went hitless in his first seven National League games. Jimmy was 0 for 29 when his ninth inning single off the Cardinals’ Slim Sallee scored the winning run in Brooklyn’s 2 to 1 win on May 12. Sebring managed only eight hits in 81 at-bats before he was released to waivers in mid-June and every major league club passed on him.

Sebring wasn’t unemployed for long. The Washington American League club quickly snapped up the free agent outfielder for a trial. Though Jimmy promised he was in shape and confident, any hope that he would regain his old prowess at the bat was soon dashed. Because of a “lame leg” and declining health, he got into only one game for the Nationals after the regular center fielder was pinch-hit for on August 6. Sebring had no chances afield and did not bat in his final appearance in a major league game. Jimmy went home for the final month of the season, but predicted that he would be ready to attend spring training with the Nationals in 1910. It became obvious that autumn that Jimmy’s decline in baseball skills was more than just rust.

Upon returning home from his job at Casper’s billiard and pool parlor on Monday, December 20, 1909, Jimmy suffered a severe seizure. He was hospitalized at the Williamsport Hospital and appeared to show improvement the following day despite his lapses in and out of consciousness. At around 5:30 p.m. on December 22 Jim suffered a violent convulsion, and his family was summoned. Elizabeth and Mary were visiting Mrs. Sebring’s father in Loganton and were unable to reach Williamsport by train for several hours. By that time it was too late. Just six years after he became a hero for hitting a home run in the first World Series game at age twenty-one, Jimmy Sebring died of kidney disease at six o’clock the evening of December 22, 1909.

An obituary in the Washington Post defined the sad plight of James Sebring; “Every town in the Tri-State League knew Jimmy Sebring, every city in the National League had admired his skill, and Cincinnati, Pittsburgh and Brooklyn had known him as a member of their teams. Jimmy never did anybody but himself harm. He was a remarkable ballplayer. His impulses were kindly, he loved the world and wanted it to love him, but everything went against him, and before 30 the health of his athletic frame sapped. He has ended the life that during its last five years knew little but bitterness… His nature was too sensitive. He couldn’t stand rebuffs; he was a shining target for unkindness. Trifles that another man would have brushed aside with complete indifference Sebring brooded over and magnified till they became tragedies, and to this habit can most of his misfortunes be directly traced.”

May 29, 2011

Sources

Altoona Mirror, August 5, 1904.

Baseball Reference.com

Gazette and Bulletin, Williamsport, Pa., July 23, 1903; August 4, 1904; August 29, 1904; June 1, 1905; July 31, 1905; September 18, 1905; September 17, 1906; July 8, 1907; and December 23, 1909.

Hittner, Arthur. Honus Wagner: The Life of Baseball’s Flying Dutchman. McFarland & Company, Jefferson, N.C., 1996, pp. 131-32.

Lyncoming County, Pa Census 1900 for John R. and Ellen Sebring; 1910 for Elizabeth Sebring.

National Baseball Hall of Fame, Giamatti Research Center, player photograph file for image of James Sebring.

Pittsburg Press, September 9, 1902; October 24, 1902; April 24, 1903; April 27, 1903; October 2, 1903; and September 4, 1904

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The Golden Age. Oxford University Press, New York, 1971, pp. 197-98.

Sporting Life, June 21, 1902; September 2, 1902; September 20, 1902, Nov 8, 1902, p. 6; November 29, 1902; May 2, 1903; May 9, 1903, May 7, 1904, May 14, 1904; August 20, 1904; December 2, 1904; May 6, 1905; June 3, 1905; May 12, 1905; June 3, 1905; June 10, 1905; November 4, 1905; November 25, 1905; March 10,1906; January 26, 1907; June 27, 1908; July 25, 1908; August 8, 1908; September 19, 1908; January 9, 1909; June 26, 1909; January 12, 1912.

The Sporting News, May 9, 1903; December 30, 1909.

Washington Post, December 23, 1909

Wiggins, Robert Peyton. The Deacon and the Schoolmaster. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011.

Full Name

James Dennison Sebring

Born

March 25, 1882 at Hoytville, PA (USA)

Died

December 22, 1909 at Williamsport, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.