Joe Frazier

Joe Frazier’s chance to manage in the majors came at the dawn of free agency and the beginning of a tumultuous period for the New York Mets, the team he led in 1976 and for two months in 1977. After a professional career as a player and manager that began before World War II, he was thrust into a major media market as “the other Joe Frazier,” far less known than the famous heavyweight boxer.

Joe Frazier’s chance to manage in the majors came at the dawn of free agency and the beginning of a tumultuous period for the New York Mets, the team he led in 1976 and for two months in 1977. After a professional career as a player and manager that began before World War II, he was thrust into a major media market as “the other Joe Frazier,” far less known than the famous heavyweight boxer.

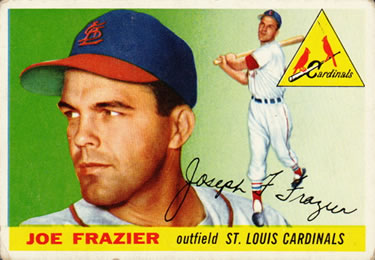

Joseph Filmore Frazier was an outfielder and pinch-hitter who played in the major leagues briefly with Cleveland in 1947 and again with the St. Louis Cardinals from 1954 into 1956, then for a month with Cincinnati and three more with Baltimore that season. Frazier led the NL with 20 pinch hits in 1954. And he homered in his last major-league plate appearance.

Frazier was born in Liberty, North Carolina, on October 6, 1922, to J. Clarence and Lacy E. (Carter) Frazier. The family’s ancestry was mostly Scottish, with some English and German mixed in. His father worked for the county and his mother worked in a cafeteria. Joe was the third of their five children: three boys and two girls. Aside from playing basketball, football, and baseball, Joe spent his childhood hunting and fishing when he wasn’t helping with household chores.1

Playing baseball was part of life for boys growing up in North Carolina, Joe Frazier Jr. said of his father’s childhood. If a youngster had talent, “It was a way to get somewhere, to stay out the mills,” he said. Hosiery and furniture mills were the biggest employers in that part of the state in those days.

Joe attended high school in Liberty before transferring to Burlington High for his senior year. There he played three sports and starred as a pitcher and third baseman, graduating in 1940.2 He also played for an American Legion team. Frazier turned down an athletic scholarship to play baseball for Elon College for Coach Horace Hendrickson, who saw a bright future for him. “Frazier handles himself like a big leaguer,” he told the Burlington Daily Times-News.3

In 1941, the Leaksville-Draper-Spray Triplets in the Class D Bi-State League offered Frazier a contract. The team was managed for part of the season by longtime major leaguer Wes Ferrell, who also pitched and played the outfield. Frazier, a left-handed hitter who was paid the princely sum of $75 a month, played third base and hit .309 with 52 extra base hits in 110 games. At the end of the season, scout Buzz Wetzel got the Triplets to sell Frazier to the Cleveland Indians organization, which sent him to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in the Three-I League for the 1942 season.4 At 19, one the youngest players in the Class B league, he finished just out of the top ten in batting with a .315 average.

Tragedy struck the Frazier family after that season. His father was returning from a hunting trip with Joe’s two brothers when a rifle accidentally discharged and killed him on November 26, 1942.5

Rather than get drafted into the Army, Joe enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard late in 1942. He still spent part of the war stationed off the coast of Italy and then off Southern France on the USS Duane.6 He remained in the service through the 1945 season. He had been able to play briefly for a semi-pro team with his brother Wendell in the Alamance Industrial League near their home while on leave in 1943.7 It was a baseball family: Wendell, usually an infielder, played and sometimes managed semi-pro teams in local industrial leagues throughout the 1940s. Younger brother Billie played minor league baseball for three years and also played with Wendell on semi-pro teams, mostly as a pitcher.

Following his discharge in 1946, brother Joe Frazier resumed his minor-league career with Wilkes-Barre in the Eastern League, where he hit .300 and made the Class A league’s all-star team as an outfielder. Among his teammates was Ray Boone. Frazier broke his thumb during the Eastern League playoffs in early September, which nixed any chance he might have had for a late season call-up by the Indians.8

Still, Frazier’s performance earned him an invitation to the Indians’ training camp in Tucson the following spring, after which he was optioned to Oklahoma City in the AA Texas League.9 He hit .276 on a team that featured Boone and future MVP Al Rosen. Frazier was recalled to the big league club in late August and on August 31 made his MLB debut at age 24, starting in right field and going hitless in four at-bats. He played in nine games before the season ended, and on September 2 got his first and only hit in 15 plate appearances, a pinch-hit double..

But he was done with the Tribe: that fall, the Indians traded Frazier along with outfielder Dick Kokos, pitcher Bryan Stephens and $25,000 to the St. Louis Browns for pitcher Bob Muncrief and outfielder Wally Judnich.

Frazier left Oklahoma with more than just another year of minor league experience. On February 15, 1948, after a courtship that began with a note passed from the stands during a game, he married the former Thelma McClure, a junior high mathematics and home economics teacher, in Tulsa.10 The couple would make their offseason home in the suburbs there and raise a family that would eventually include Joe Jr., born in 1950, daughter Cindy two years later, and son Marty, born in 1955,who went on to graduate from West Point.

After spending spring training in the Browns’ camp in 1948, he was sent to the team’s San Antonio affiliate in the Texas League, where he hit .267. The next year he split between AA San Antonio, hitting .289, and AAA Baltimore, where he struggled, hitting .175 in 23 games. Back at San Antonio in 1950, and now 27, he hit .265. After a contract dispute and a .233 start in 29 games with San Antonio – his fifth season in the Texas League – Frazier was moved to Memphis in the AA Southern Association. He hit .269 there but knocked 13 home runs, a career high at that point for a single team. At least it wasn’t San Antonio where Frazier, a dead pull hitter, had been frustrated by a strong wind blowing in almost constantly from right field. “He was hard-headed,” Marty Frazier said of his father. “He kept trying to hit the ball out to right.”11

Before the 1952 season, the Browns sold Frazier outright to Oklahoma City. The move seemed to rejuvenate Frazier, who hit .294 with 14 homers. He reached the heights the following season: a league-high .332 average, 55 doubles, 22 homers, 113 runs batted in and 105 walks, an easy choice for Texas League Player of Year for 1953. On October 13, Oklahoma City traded Frazier to the St. Louis Cardinals for catcher Les Fusselman.

Now 31, Frazier made the Cardinals team out of spring training. His bat speed and stance impressed manager Eddie Stanky, nicknamed him “Cobra.”12 Frazier quickly settled in to what was to be his primary role: a left-hand batting pinch hitter. His 69 appearances pinch hitting led the majors in 1954. He hit .323 as a pinch hitter, and of his league-leading 20 pinch hits, nine went for extra bases: three homers, two triples and four doubles. Frazier appeared in just 12 games in which he did not pinch hit: driving in 18 runs on 26 hits. He hit .295 overall and achieved a nice .388 on-base percentage.

On July 18, 1954, Frazier had a solo homer erased from the books. With the Cards down 8-1 in the top of the fifth to the Phils in the second game of a double-header in St. Louis, the umpires—misinterpreting a league directive—refused Stanky’s request to have the stadium lights turned on. Stanky pulled his team from the field, and Philadelphia won by a forfeit. Because the game hadn’t gone a full five innings, the records were wiped out.13

That fall, Frazier joined a barnstorming tour of major leaguers playing Negro League all-stars throughout the Southwest and (at least as intended) Mexico. Paltry crowds and bad weather forced cancellation of the last 12 games of the tour, however.14 Frazier then went to Venezuela, as he had the previous off-season, to play winter ball.

The 1954 season would be the high point of his MLB career. Although he hit another pinch-hit home run in 1955, he went just 3-for-41 as a pinch batter. A month into the 1956 season, the Cards traded him and infielder Alex Grammas to the Redlegs for outfielder-third baseman Chuck Harmon.

Frazier played for three teams in 1956 and hit a homer for each one. His last—a solo shot off Ted Abernathy before just over 3,000 fans at Griffith Stadium— came in the ninth inning of the season’s final day, the second game of a doubleheader on September 30, 1956. The game lasted less than two hours. Just like that, Frazier’s big-league career ended.

He kept plugging away in the minors for another four seasons, remaining in the Orioles organization with AAA Vancouver until he was dealt to the Dodgers in December 1959, part of a deal involving five minor players. He saw consistent playing time at AAA until his final season in 1960, when he hit just .210 in 56 games for Spokane.

With his playing career winding down, Frazier and his wife purchased a 40-acre pecan farm outside of Tulsa in 1959. With help of Joe Jr., Frazier spent his off-seasons tending to the pecans on land that remains in the Frazier family.15

Early in 1961, Gabe Paul, the first general manager of the expansion Houston Colt .45s, offered Frazier a job as a scout, responsible for Oklahoma and three other states. Frazier was Paul’s last hire before he moved on to Cleveland. Paul Richards, who had been Frazier’s manager when both were with the Orioles became his new boss. Frazier’s territory later included the Northwest, where he was often at minor league games with Athletics scout Whitey Herzog, who later became the director of player development with the Mets.16

Frazier’s first chance to manage came in the fall of 1965, when he led the Bradenton Astros to a first-place finish in the Florida Instructional League. The next season, he managed Houston’s Cocoa team to an 81-55 record, in the Class A Florida State League, but Houston’s management told him he was too hard on the young players.17

Frazier spent the next season as a hitting instructor in the Astros system before Herzog offered him a job managing in the Mets organization.18 He took over Mankato (Minnesota) in the Class A Northern League in 1968 and then Pompano Beach in the Florida State League in 1969, before spending the next three seasons with Visalia in the Class A California League. His 1971 Visalia team won the playoff for the league title. In 1973, he began two seasons managing in the AA Texas League, leading Memphis and Victoria to first-place finishes.

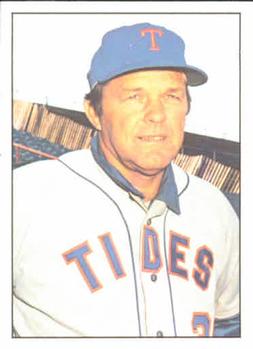

Frazier guided the Mets AAA farm club at Tidewater to the International League pennant in 1975, and The Sporting News named him Minor League Manager of the Year. He won two rounds of playoffs before losing the Junior World Series to Evansville of the American Association.

Frazier guided the Mets AAA farm club at Tidewater to the International League pennant in 1975, and The Sporting News named him Minor League Manager of the Year. He won two rounds of playoffs before losing the Junior World Series to Evansville of the American Association.

The Tides had finished at the bottom of the IL the previous season, but Frazier promised the team would show more fight under his leadership. “When we lose, I want our guys to die a little like I do,” he said before the season.19

The parent club, meanwhile, was treading water with strong pitching but little offense. In early August with the Mets three games over .500, the team fired Yogi Berra as manager. Interim replacement Roy McMillan did no better, and the team ended up 82-80. (Actually, the chairman of the Mets ownership board, M. Donald Grant, said the team had considered moving Frazier up to replace Berra in August, but because Tidewater was in a pennant race, Frazier was kept with the AAA team.)

Days after the season ended, the Mets, on the recommendation of general manager Joe McDonald, turned to the little-known Frazier to lead the team in 1976. “I’ve seen some great athletes, some great golfers, who couldn’t teach a lick. I try to teach,” Frazier said at the October 4 news conference introducing him as the new skipper. “I don’t have any special philosophy. … I just believe in fundamentals.”20

A 17-day union-management dispute triggered by the beginning of free agency delayed the start of spring training in 1976. Consequently Frazier had less time to evaluate for himself the team’s strengths and weaknesses. “I’m going to have to rely on my coaches’ opinions because they know the older guys. … Getting acquainted with what each individual can and can’t do. … That’s what I consider my big job,” Frazier said during the shortened spring training.21 The coaches he had to rely on were not of his own choosing. Grant decided that all four coaches under Berra, including McMillan, would be retained.22

The Mets got off to a good start. After winning on May 8 before a Saturday crowd of more than 41,000, the team was in first place at 18-9. But the team plummeted: after losing on June 22, the Mets fell four games under .500. A strong September allowed the team to finish at 86-76, despite the Mets losing the season’s last five games.

The team’s uneven performance and lack of hitting wore on Frazier. During the see-saw season, some of the players began grumbling about his frequent lineup changes as he struggled to find winning combinations. Pitcher Jon Matlack complained to Frazier about slugger Dave Kingman’s lackadaisical fielding, but the manager said he didn’t like to talk to Kingman “because he pouts.”23 Still, Frazier remained well-liked. Joe Torre was one of his biggest boosters. “When I had a bad day, he was always there. He recognizes when somebody needs that or a boot in the butt. The players respect him for that.”24

The Mets seemed pleased also. On August 12, the team renewed Frazier’s contract for 1977. “I feel I have done a good job in the face of the circumstances — the injuries the team has suffered and the other problems,” Frazier said after a loss to San Diego.25 Indeed, the team’s already anemic lineup was crippled when Kingman, leading the league in homers, tore a thumb ligament diving for a ball on July 19.

Clearly, the Mets needed more offense to complement the starting pitching of Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, and Matlack. Instead, the front office, stymied by the tight-fisted Grant, did little to improve. The only significant addition to the offense was Lenny Randle, obtained in a trade with the Rangers in what seemed at the time to be a minor deal. Otherwise, the 1977 Mets had to rely on youngsters such as Lee Mazzilli, John Stearns, and Nino Espinosa. Several veterans, including Seaver, openly criticized management, while Matlack and Kingman wanted to be traded. Frazier, although outwardly optimistic, knew the Mets would have trouble winning and that his job soon would be in jeopardy.26

He wasn’t wrong. After splitting the first 18 games, the Mets quickly fell to 11-21, the second-worst start in team history (the 1964 Mets were 10-22 at that point in the season). With no proven bats added to the lineup and question marks at second, third and center, Frazier used 34 different batting orders in the first 45 games. A loss to Montreal on May 30 left the team’s record at 15-30. “He hasn’t cracked up,” outfielder Bruce Boisclair who played for Frazier in the minors, quipped. “If I was managing this team, I’d be a nervous wreck.”27

Indeed, the ax fell on the afternoon of May 31 during a meeting at Grant’s Wall Street office that included Frazier, McDonald, and Torre, who was named as the new manager. As they rode together back to Shea Stadium, “I think Joe Frazier was the calmest of the three of us,” Torre said. “Joe Frazier has done a good job for us in difficult times,” McDonald said at a hastily arranged press conference. “He was placed in a situation where some of our players were difficult to get together.”28

Grant, who hadn’t sought to sign any of the newly free agents, seemed not to grasp the depth of the dissension. “Donald Grant envisions his Mets as one big happy family. Forget it. They are not. Hardly a day passes that there is not some new conflict,” Jack Lang wrote in The Sporting News after Frazier’s dismissal.29

Two weeks after Frazier was fired, Grant pulled the trigger on a trade that would go down in infamy among Mets fans, sending Seaver to the Reds for what proved to be four journeymen ballplayers. Grant also jettisoned the disgruntled Kingman. The slide that began under Frazier continued throughout his successor’s five-year tenure. The Mets lost 95 or more games every year through 1980. Torre was fired after the strike-shortened 1981 season, and the team would not regain respectability until 1984.

Following his tenure as manager, Frazier remained with the Mets as a roving scout until being hired in the same capacity by Herzog, then managing the Cardinals.30

Frazier’s last managing job came with AAA Louisville, the Cardinals top farm club, in 1982. Ken Boyer, who had been scheduled to manage the team, stepped aside after he was diagnosed with lung cancer, which claimed his life in September. Herzog asked Frazier to take the job. The team finished 73-62, tied for the second best record in the American Association. Frazier continued to scout for the Cardinals until he retired in the mid-1980s.

Frazier spent much of his early retirement on the links; his house in Broken Arrow abutted a golf course. A skilled amateur golfer, he regularly finished his rounds in the 70s. When his wife Thelma developed Alzheimer’s, he cared for her until she died in 1998, not long after they celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. Four years later, at age 79, he married the former Jean Pence, who also had lost her spouse.31

Frazier himself died of a heart attack, according to his wife Jean, on February 11, 2011, in Broken Arrow at age 88. He is buried in Bixby Cemetery in Bixby, Oklahoma.

According to his son Marty, his father had that competitive instinct common in professional athletes: He hated to lose. “He stopped playing chess with me when I kept beating him.” Challenged to a swimming race by his father, Marty recalled how he felt a hand tugging on his trunks, trying to hold him back when he was pulling away. “He played to win,” Marty said. “If there was no chance of winning, he didn’t want to play. If he had a player who didn’t care about winning, he couldn’t play for my dad.”32

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my appreciation to Joe Frazier’s sons, Joe Jr. and Marty. for their assistance with this essay. It was reviewed by Tom Schott and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 Telephone conversation with Joe Frazier Jr., May 8, 2017.

2 Ibid., with Marty Frazier.

3 Ed Storey, “Joe Frazier, Former High School and Legion Baseball Star Is Now Success On Cedar Rapids, Ia., Team,” [Burlington, NC] Daily Times-News, May 26, 1942: 6.

4 Ralph Blumenfeld, “Man in the News: Mets Joe Frazer/Wait Till Next Year,” New York Post Magazine, October 11, 1975: 2.

5 “Father Of Local Man Killed While Hunting Near Liberty Thursday,” [Burlington, NC] Daily Times-News, November 27, 1942: 2.

6 See note 1; Blumenfeld, “Man in the News…”

7 “Fifth Win Is Chalked Up By Hooks Calloway,” [Burlington, NC] Daily Times-News, July 3, 1943: 11.

8 Effie X. Welsh, “Did You Know That?” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, September 12, 1946: 23.

9 “Joe Frazier Sent to Oklahoma City,” Tucson Daily Citizen, April 15, 1947: 10.

10 Marty and Joe Frazier Jr. conversation.

11 Marty Frazier conversation.

12 Joe Frazier Jr conversation.

13 Bob Broeg, “Cheers for Forfeiture Spur Cards Manager to Apology,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1954: 5.

14 “Rain, Poor Crowds Kayo Kretlow Tour,” The Sporting News, November 3, 1954, 22.

15 Joe Frazier Jr. conversation.

16 “Gabe Signed Scout Frazier in Last Move as Colt’s Boss,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1961: 9; conversation with Marty Frazier.

17 Baseball Reference lists Frazier as 1965 manager of the Red Sox team in the Florida Instructional League, but Marty Frazier confirmed the information in his father’s clip file at Giamatti Research Center that Joe Frazier managed Houston’s team at Bradenton.

18 Ibid.

19 Clipping, Dave Lewis, “Frazier wants ‘cocky’ Tides ‘to die a bit when we lose,’ [Norfolk VA] Ledger-Star, Norfolk, Virginia, January 27, 1975, page unknown (from Frazier’s clip file at HoF Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, NY).

20 Joseph Durso, “Mets Appoint a Manager From the Minor Leagues,” The New York Times, October 4, 1975: 1.

21 Jack Lang, “’Getting to Know You’ Frazier Theme Song,” The Sporting News, April 3, 1976: 45.

22 Ibid., “Grant Calling Shots on Mets Tutoring Staff,” November 1, 1975: 24.

23 Ibid., “Mets Look Up But Problems Still Smolder,” July 10, 1976: 8.

24 Ibid., “Torre Finding Genuine Happiness in ‘Fun City’,” , May 29,: 17.

25 Dave Sims, “Mets Rehire Frazier; Padres Zip Tom, 3-0,” Daily News, New York, August 13,: C22

26 Marty and Joe Frazier Jr. conversations.

27 Tony Kornhesier, “Joe Frazier’s Week That Was: Death Watch Dies for Now,” New York Times, May 22: 169.

28 Lang, “New Skipper Torre Ends Mets’ Juggling Act,” The Sporting News, June 18, 1977: 9; Joseph Durso, “Mets Dismiss Frazier and Select Torre as Manager,” ibid., June 1, 1977: 1.

29 Lang, “Dissension? It’s Name of Game on Sinking Mets.” The Sporting News. June 11, 1977, 8.

30 Marty Frazier conversation.

31 Previous paragraphs based on Joe Frazier, Jr. conversation.

32 Marty Frazier conversation.

Full Name

Joseph Filmore Frazier

Born

October 6, 1922 at Liberty, NC (USA)

Died

February 15, 2011 at Broken Arrow, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.