Joe Quinn

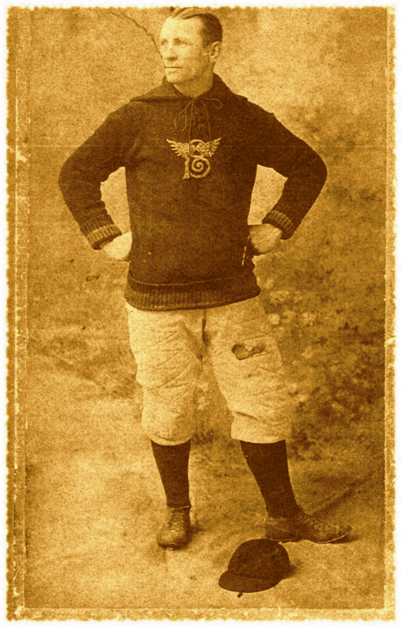

Joe Quinn’s 17 seasons between 1884 and 1901 marked the first appearance by an Australian in major league baseball. For 102 years, Quinn was the only player from “Down Under” to feature at the top level of American pro ball, and he remains the only Australian to manage in the major leagues. He played on the team with the best winning record in major-league history — the St. Louis Unions of 1884 — but in 1899, captained and managed the Cleveland Spiders to the worst win-loss percentage in big-league history. The little second baseman, who worked as an undertaker in the off-seasons, was enormously popular, both for his skill and earnestness on the diamond and his spotless reputation off it: in 1893, he was voted “America’s Most Popular Player” in a Sporting News public poll. In an era characterized by a constant tug-o’-war for player services, Quinn was the glue that held together teams rent by ruthless owners, failing finances, and broken spirits. He often took the helm when no one else would, embodying the unique Australian quality of “having a go” even in impossible circumstances.

Joe Quinn’s 17 seasons between 1884 and 1901 marked the first appearance by an Australian in major league baseball. For 102 years, Quinn was the only player from “Down Under” to feature at the top level of American pro ball, and he remains the only Australian to manage in the major leagues. He played on the team with the best winning record in major-league history — the St. Louis Unions of 1884 — but in 1899, captained and managed the Cleveland Spiders to the worst win-loss percentage in big-league history. The little second baseman, who worked as an undertaker in the off-seasons, was enormously popular, both for his skill and earnestness on the diamond and his spotless reputation off it: in 1893, he was voted “America’s Most Popular Player” in a Sporting News public poll. In an era characterized by a constant tug-o’-war for player services, Quinn was the glue that held together teams rent by ruthless owners, failing finances, and broken spirits. He often took the helm when no one else would, embodying the unique Australian quality of “having a go” even in impossible circumstances.

Joseph James Quinn was born on December 24, 1862, in the village of Ipswich, Queensland, in northern Australia.1 His parents, Patrick Quinn and Catherine McAfie, were both refugees from the Irish Potato Famine. The son of an impoverished farmer in County Laois, Ireland, 17-year-old Patrick came to Australia on a one-way ticket in 1855, his passage subsidized under the British Assisted Immigration scheme.2 Born in about 1830, Catherine was raised as a servant on a farm near Enniskillen in what is now Northern Ireland, and orphaned by the famine while still a teen.3 Her ability to read and write allowed her to escape the county workhouse and find another servant’s position in 1847; it took a further six years for her to save her fare to Australia.4 Catherine and Patrick met in the small Irish enclave of Broulee on the New South Wales south coast in 1856; though she was eight years his senior, within weeks, they were married.5

In 1857, Patrick took his new bride to the Araluen goldfields near the modern-day Australian capital of Canberra, where their first son, Patrick Jr., was born.6 The diggings were destroyed by a monster flood in 1860, and the Quinns, who had failed to make their fortune at Araluen, now journeyed 600 miles north to Ipswich, chasing rumors of work on a new inland rail line.7 When Joe was born on Christmas Eve in 1862, the family was sweltering in a tent in a squatters’ camp outside town, with only potatoes and feral goat for their Christmas dinner.8

Patrick Quinn made a paltry living laboring on Queensland’s first rail line, which opened in July 1865.9 By that time, the state was gripped by drought, failing crops, and riots over unemployment. The Quinns escaped by walking all the way south back to the Irish settlement at Campbelltown, just west of Sydney. This was the harshest period of Joe Quinn’s life. Founded as a British penal colony in 1788, Australia’s convict era was now over, and prison labor was replaced in many cases by underpaid child workers. Joe Quinn was one of 37,000 Australian children who worked as factory hands, farm workers, and domestic servants in the year 1871 alone.10 He bent his small body for a few pennies a week, only attending school intermittently. There was no time or money for games and sports. But by 1872, when Quinn was 10 years old, his family was down to their last pennies. Hailstorms and wheat rust had decimated local agriculture and many families were bankrupt and unemployed.11 Having not found their promised land in Australia, the Quinns took ship for the United States.

They settled in Dubuque, Iowa, after a journey of 11,000 miles by ship, stagecoach, and countless miles of painful walking.12 A large Irish diaspora had settled in the village beside the Mississippi River after the post-Famine exodus, so much so the town became known as Little Dublin. Perhaps finally feeling at home after almost two decades of wandering, Patrick Quinn settled his family in a small house on Grandview Avenue, where he remained until his death in 1902.13

But in Dubuque, little changed for 11-year-old Joe Quinn. His family, still immigrants, still uneducated, faced the same grinding poverty, with the Australian farms now exchanged for Iowa’s zinc mines.14 His father took a job in the Avenue Top mine and exaggerated Joe’s age to get him a job underground too, shifting rubble and shoring up walls on just 50 cents a day.15

Thus far, sports had played no part in Joe Quinn’s underprivileged life. In Australia, the game of baseball had existed only among American expats on the goldfields.16 But in Dubuque, “all the boys played,” as Quinn said in a later interview.17 At 16 years old, Joe Quinn had struggled to integrate with these local children: he spoke differently, he was a dirty half-educated miner’s boy who was beneath their contempt. In baseball, he at last found some common ground.18

Despite his late start in the game, Quinn clearly showed some natural ability. Within three years, in 1881, he was invited to join the local semi-pro team, the Dubuque Rabbits, playing alongside future Hall of Famers Charles “Hoss” Radbourn and Charlie Comiskey.19 Quinn played first base as understudy to Comiskey. He stood just 5-feet-7, and at 150 pounds, was hardly an intimidating presence for the oncoming baserunner — but Joe Quinn had become battle-hardened in the mines, and in this era of gloveless play, his tough hands were perfect for taking throws on bare palms.

On the national stage, unrest was high in professional baseball. The National League and American Association squabbled relentlessly over players, admission prices, and salaries. Players jumped back and forth between leagues searching for the best pay and conditions. In response, both leagues adopted the reserve clause, allowing clubs to indefinitely hoard their best five players. In 1883, reserve quotas were hiked from five to 11.20 In response, St. Louis millionaire Henry Lucas established the Union Association, boldly snatching talent from the established leagues and the semi-pro ranks with lofty salaries and no reserve clause.21 Joe Quinn was engaged for Lucas’s St. Louis team, the Maroons, for $2,000 — a sum that would have bought passage from Australia to the USA 50 times over.22

Just before his departure from Dubuque in late 1883, Quinn took a night-time walk which nearly ended his baseball career. A section of rotten sidewalk gave way, sending him crashing down an embankment. Quinn was forced to sail down the Mississippi River for St. Louis with his broken arm in a splint, for which he later sued the City of Dubuque for $2,500 damages.23 It was hardly the perfect preparation for the rough and rowdy world of professional baseball, where brawling, cheating, and hard drinking were a way of life and two good fists were often needed to earn a player a break, as Quinn himself later recalled.24 The violence often included brutal victimization of rookies. Quinn gave up 70 pounds to some of his hulking teammates, who pitched balls at his head, tore his uniforms, and complained he was too small to play first base.25

But Quinn’s hard upbringing had instilled in him a fierce self-respect: he refused to retaliate, instead letting his play do the talking. In his major-league debut on April 26, 1884, against Altoona, he banged his first hit in pro ball over the shortstop’s head and scored from third in the 9-3 victory. He then cemented his place in the team with an errorless four-game series at first base, St. Louis averaging 14 runs per game while the Pennsylvania outfit scored just 12 for the entire series.26 One hundred and two years passed between Joe Quinn’s debut and another Australian appearing in major-league baseball, when Craig Shipley lined up at shortstop for the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1986.

In 1884, St. Louis decimated the breakaway Union Association. Their 94-19 win-loss record remains unsurpassed in professional baseball. Quinn hit a respectable .270 and handled over 1,000 putouts at first base. He also appeared briefly in the outfield and at shortstop, as he would on occasion in years to come. However, the Union Association was so top-heavy it collapsed after only one season. While some baseball observers have questioned its classification as a major league,27 as baseball’s first attempt to protect the rights of professional players, it awoke in Joe Quinn a desire for justice which would shape many of his future choices.

What followed was two years of humiliation for the Maroons franchise as it joined the National League and was immediately blown away by the higher caliber of pitching and defense. The Maroons finished the 1885 season dead last, and 1886 was little better. Quinn was shunted around the infield and then, because he had been timed sprinting 100 yards in under 11 seconds,28 dispatched to right field, from where he was expected to throw runners out at first base. His batting average hovered around .220. By November 1886, the Maroons were bankrupt and out of the league.

With a scarcely-impressive three seasons behind him, baseball oblivion beckoned for Joe Quinn. But an opportunity came in Duluth, Minnesota, on the icy shores of Lake Superior. That Northwestern League club had lost its second baseman, John Ake, in a boating tragedy on the Mississippi, and were scrambling mid-season for a replacement.29 The entire Maroons franchise had been sold to Indianapolis but, with a top-heavy list of infielders, Quinn had not played a single game, and owner John T. Brush agreed to sell his “extra fielder” to Duluth, despite Quinn having played just 15 games at second base in his entire professional career. Quinn could do nothing but “have a go,” in the great Australian tradition.30

Joe Quinn had hit only one home run in his pro career. Now, in 1887, he slammed 11 and posted a .372 batting average. He was made captain, then manager, of the Freezers.31 But squabbling board members and financiers were crippling the club. Quinn stood by his struggling team — even when management proposed selling him to raise capital, Quinn refused to desert his sinking ship and consent to the sale.32 His loyalty, however, came to naught: the club finished seventh in the eight-team league and was disbanded.

Quinn returned to St. Louis for the winter of 1887-88, where he boarded in the Irish enclave known as the Kerry Patch.33 Nineteenth-century players were paid only during the season, and many worked during the winters to keep their heads above water until next spring. There were showmen and preachers, trappers and teachers.34 In 1886, under the wing of Kerry Patch mortician Thomas McGrath, Joe Quinn had become an apprentice undertaker.

The funeral business was dangerous as it was somber. Undertakers inhaled arsenic and mercury from embalming fluids, and were exposed to diseased corpses without the protection of face masks, gloves, or antiseptic.35 Quinn’s decision to enter the industry arose from a great fear of returning to his childhood destitution:

“I realized I only had a limited period as a player, and seeing all about me great stars doomed after their playing days to poverty and often starvation, I determined that when my time came, there would be no such story told about me.” 36

Quinn drove himself fiercely through the winters, working for McGrath and earning extra cash shoeing horses37 and tending bar.38 But while it was gloomy and hazardous, the association with Thomas McGrath had a special advantage for Joe Quinn. McGrath had four daughters, and one in particular caught Quinn’s eye — Mary Ellen, a spirited girl with auburn hair and blue eyes, was six years his junior, and saw much in Quinn beyond the vile reputation many ball players had for drinking, fighting, and gambling. They were married on November 17, 1886, at St. Bridget’s Catholic Church in St. Louis.

In 1888, Quinn signed with Des Moines in the Western Association to play second base for the Prohibitionists.39 In this temperance heartland, teetotaler Quinn was their poster boy. On a diet of pork and corn, he filled out to over 170 pounds and helped himself to a .309 average in 77 games.40

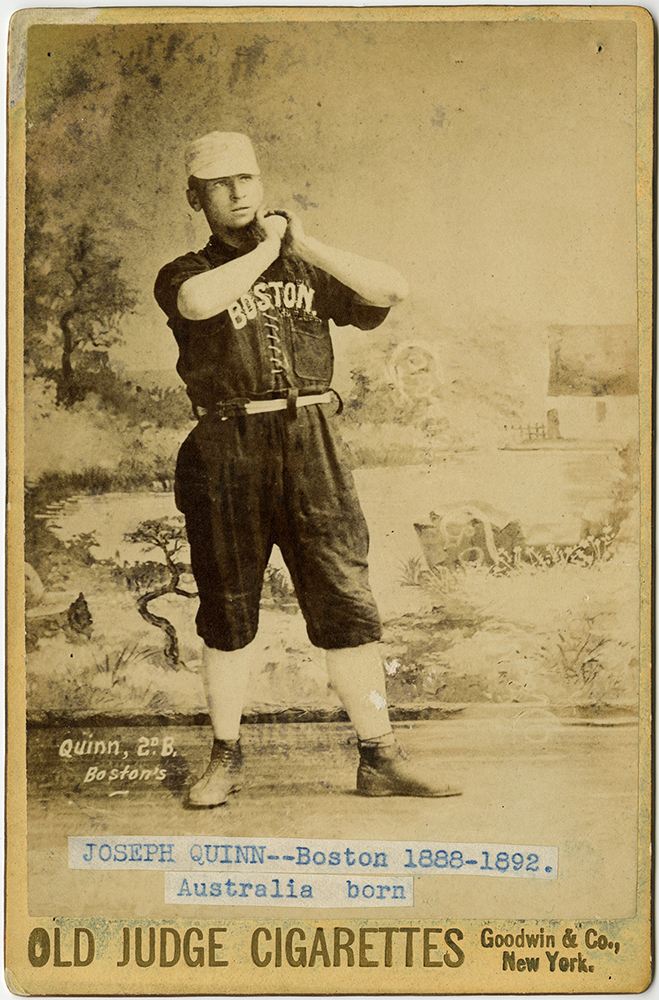

Back in the National League, baseball’s richest club, Boston, had a problem. In 1888, they had already tried and sacked three second-basemen, two of whom couldn’t hit and one who fractured his skull falling off a tram.41 The solution — tempt the Prohibitionists with $3,000 for the in-form Joe Quinn.42 But once again, Quinn would not break his contract. The offer increased to $4,000; Quinn again refused. However, the Prohibitionists were in financial trouble, and in August, they handed over his contract.43 Quinn was furious. It was a terrible realization that he was merely a commodity to be traded, and to have the public potentially perceive him as a greedy jumper was abhorrent.

Boston wanted Quinn before facing league-leaders New York at the Polo Grounds on August 27. In New York, Quinn faced such a riotous crowd of Giants fans that the overflow of their carriages had to be parked in center field. The game was titanic. The Beans took the lead in the third inning as speedy Dick Johnston hit safely, stole second, and came home on a Tom Brown hit which Giants outfielder Mike Slattery allowed to bounce. But the Giants equalized at the top of the ninth; two Boston hitters fell trying for the winning run — and with the crowd raising a din audible for miles, out of the dugout walked little Joe Quinn.

Giants pitcher Tim Keefe was on a 19-game winning streak; he had already struck out 10 that day. But Quinn looked Keefe straight in the eye and swung hard at the first pitch. The hit soared over center fielder Slattery’s head to land among the carriages. Scrambling Giants fielders couldn’t disentangle the ball before Quinn slid in for the winning run, the strangest inside-the-park home run of the year.44

In 1884, Quinn had been a part of baseball’s first rebel league. As the 1880s drew to a close, insurrection again threatened professional baseball. Front and center was Boston crowd favorite Joe Quinn.

Since his dramatic debut for the Beaneaters, the Boston public had clamored to know the serious young man from “Down Under.” Quinn had been taken under the wing of the team’s greatest celebrity, Hall of Fame catcher Mike “King” Kelly, who guided him through the minefield of life in the spotlight. Kelly and Quinn were baseball’s most improbable pairing. Unlike the sober Quinn, Mike Kelly loved nothing more than strong drink, fine food, and betting on horses. But he won two batting crowns in the 1880s, and his inventiveness required constant changes to baseball’s rules.45 Kelly’s parents had died soon after he was born, and it was perhaps his lifelong quest for love and attention that drew the King to Quinn, whose modesty was the perfect foil for his own exuberance.46 In the reflected glow of Kelly’s brilliance, Quinn had thrived in his return to the big time. He hit .301 in 38 games in 1888 and recorded over 200 putouts at second base. Boston fans presented him with a gold-inlaid bat in September 1889, with which Quinn promised he would hit a home run. The best he could do was a hard-hit single, but the crowd still raised the roof.47

But 1889 was a rollercoaster season for Boston, who lost the pennant to New York amid bitter infighting, much of which fans blamed on Kelly. The King’s staunchest defender was Joe Quinn, even when he too was vilified:

“Some of my friends are sore on me for upholding Kelly. Well, Kelly acted like a gentleman when I first went to Boston. He could not do any more for his brother than he did for me.”48

There was also ongoing unrest in the National League. Conflict over the reserve clause was inflamed by introduction of the Classification Rule to cap player payments. To the Brotherhood of Base Ball Players, the players union formed to fight the reserve clause, this attack on player rights could not go unpunished.49 Quinn was privy to the union’s secret plans to form a breakaway league in 1890.50 On September 21, 1889, The Sporting News published a letter from a “leading Boston player” trumpeting the plan:

“We have concluded to start an association of our own and ask no more favor from the directors of the league…No matter what happens, do not mention my name in connection with this letter.”51

Quinn admitted he had authored the letter, with the support of the Brotherhood.52 Over 100 of the era’s greatest players, including King Kelly, Hoss Radbourn, Charlie Comiskey, and Tim Keefe, now openly rejected the strictures of the reserve clause and prepared to join the rebel league.53

However, Quinn hesitated at the 11th hour. After his poverty-stricken childhood, he was suddenly nervous about litigation — he had saved hard throughout his career but now could lose everything if the National League’s lawsuits against the Players’ League succeeded.54 But the ever-loyal Quinn did sign with the Boston Reds. And in the company of many of the game’s greats, he enjoyed his best year on the diamond so far. He had 153 hits — including seven homers, his best single-season total in the majors — for an average of .301, well above the league average .274. He stole 29 bases (also a career high) and led the league in fielding percentage at second base (.942), the first time he did so.

“Joe Quinn is the most valuable second baseman in the Players’ League. His sacrificing won many a game, he is among the leaders in batting, has the highest fielding average of the League and tries for everything. He has been a gold find.”55

The Reds were the champions of the Players’ League, which collapsed after its only season in 1890. Quinn returned to the Beaneaters and won a further two National League championships with Boston in 1891 and 1892. However, the 30-year-old was supplanted by younger infielder Bobby Lowe at the end of 1892. Not only did Boston let Quinn go — they sold him to one of the league’s weakest teams, the St. Louis Browns.

The Browns had won four American Association pennants in the 1880s and had finished either second or third from 1889 through 1891. After joining the National League in 1892, however, the club spiraled downward into 11th place out of 12. The Browns needed a captain who would both lead the struggling team and liaise with the capricious owner, Chris Von der Ahe — a task requiring a hide as thick as the proverbial rhinoceros.56 In February 1893, Joe Quinn arrived to captain and play second base for the Browns. The Sporting News observed:

“The selection is a wise one…Unlike many other professionals, he has never broken a contract or been charged with double-dealing of any kind. He is honest and upright and commands the respect of the fraternity at large.”57

Quinn now took the greatest gamble of his baseball career. After years of being apprenticed to Thomas McGrath, Quinn bought his own business, a livery stable in the Kerry Patch. In the 19th century, livery and undertaking services worked symbiotically, with transport to and from the burial complementing the funeral services. Working during the playing season was unheard of for professional ball players, yet Quinn was now stabling horses, renting buggies, transporting the bereaved, and somehow fitting it all around his numerous duties on the ballfield.58

He managed, initially: in fact, in mid-May of 1893, Quinn and his Browns were actually leading the league.59 The captain had laid down firm guidelines for the discontented squad:

“People will not patronize the sport if they are compelled to listen to the language of swell-headed toughs…If these offenses are repeated under me, you will quit ball-playing for all time.”60

But it couldn’t last. As the Browns began to slip back toward the cellar, Von der Ahe berated, fined, and suspended his players for every minor error. Morale crashed. Quinn himself was exhausted by practice, travel, and hours of extra labor in the stables. His batting average was under .240, and only fumbling third baseman Jack Crooks made more errors.

The one bright spot came on September 30, 1893, when the Browns, having lost their previous 10 games, crushed league-leaders Boston in both games of a doubleheader during which Quinn hammered eight hits.61 This performance coincided with his decision to sell the Kerry Patch stables.62 Quinn’s pride was wounded at having to return to working for McGrath, but an unexpected reward came his way. In one of the worst seasons of his career with both bat (.230 average) and glove (.942 from 135 games), Quinn was voted “America’s Most Popular Player” by The Sporting News, with its readership of 80,000. The award was proof that Quinn didn’t need to play for a winning team or produced Hall of Fame numbers to be respected and admired. He wore the gold watch presented to him for the rest of his life, albeit tucked deep in a pocket lest it mar his sober image.63

The one bright spot came on September 30, 1893, when the Browns, having lost their previous 10 games, crushed league-leaders Boston in both games of a doubleheader during which Quinn hammered eight hits.61 This performance coincided with his decision to sell the Kerry Patch stables.62 Quinn’s pride was wounded at having to return to working for McGrath, but an unexpected reward came his way. In one of the worst seasons of his career with both bat (.230 average) and glove (.942 from 135 games), Quinn was voted “America’s Most Popular Player” by The Sporting News, with its readership of 80,000. The award was proof that Quinn didn’t need to play for a winning team or produced Hall of Fame numbers to be respected and admired. He wore the gold watch presented to him for the rest of his life, albeit tucked deep in a pocket lest it mar his sober image.63

Freed from the demands of his business, Quinn’s 1894 form had been much improved. In partnership with new shortstop William “Bones” Ely, the pair were hailed the best infield duo in the league.64 But it all came undone on the Fourth of July when Quinn, who had made three hits and turned three double plays against Washington, had his hand smashed by an errant pitch.65 His absence saw the Browns began their familiar backslide, and Von der Ahe slashed all salaries as punishment. With his hand only half healed, Quinn hastily reinstated himself — but by August, the players had not been paid in months and finished the year in ninth place.66 Despite his shattered hand, Quinn finished the year second in the league in fielding at second base (.952), making just 34 errors in 106 games. The Browns finished the year ninth.

Between 1894 and 1898, the Browns had 13 managers, and the team’s performances degenerated from the uncertain to the preposterous. The 1895 season was just eight weeks old when the yoke landed on the shoulders of Joe Quinn.

By late June 1895, Von der Ahe had already dispensed with two managers for the season. The Browns’ performances had been so awful that fans were booing and whistling Handel’s Dead March every time they took the field.67 It seemed only Quinn could resist the slide toward the National League cellar, hitting .362 for the year. It was no romantic transition, however: the Browns lost their first seven games under Quinn’s stewardship.68 But on July 25, Quinn slammed four singles and a double against Brooklyn to drag the Browns out of another six-game losing streak,69 and Sporting Life reported:

“The Browns are doing better, much better, under the direction of Manager Quinn. There is more harmony in the club, less chance for jealous differences, and when a few broken fingers and wrecked joints have got into normal condition, still better results may be looked for.”70

It was the last good thing said about the Browns during Quinn’s reign — they won only one of his remaining 11 games in charge. Quinn was still batting .347 but he cabled his notice as manager to Von der Ahe on August 4, insisting that the best way he could serve the club was to focus on playing.71 Despite earning the respect of his men through his honesty and integrity, Quinn was never comfortable in the role of manager. Off the field, he was a loner, and he admitted he lacked the genuine connection with the players which distinguishes the captain from the general.72

Over the next 12 months, the Browns had a further seven managers and many players were sacked or traded for minor offenses. In July 1896, Von der Ahe issued the ultimate warning to the demoralized team: he traded their most consistent player, Joe Quinn, to Baltimore.73 It was the crowning insult in the entire debacle — the man with the cleanest reputation in baseball was sold to its dirtiest team.

Despite winning National League championships in 1894 and ’95, the Baltimore Orioles were just as well known for hustling, fighting, and outright cheating. Their star-studded roster included Hall of Famers John McGraw, Hugh Jennings, Joe Kelley, and Wee Willie Keeler, and Quinn now faced a major test of his integrity — how to earn the respect of his fractious new teammates without compromising his own pristine reputation. But Joe Quinn was no pushover. After years of maltreatment in St. Louis, he bloomed in the Baltimore hothouse. His batting average revived to .329 in 24 games as the bad Birds clinched the 1896 pennant. They had the best winning percentage in Baltimore major-league history with their 90-39 record.74 Quinn recounted:

“If a man didn’t get out and do battle, he didn’t last long. The players were a rip-snorting lot and it took a good two-fisted fellow to make his own breaks.”75

In 1888, Australians had been formally introduced to baseball when the Chicago White Stockings and American All-Stars played 12 games there as part of the Spalding World Tour. An ambitious return tour of the United States by Australian players was organized in 1897. But for all the players’ enthusiasm, the self-financed Australian team was routinely humiliated by its American counterparts. By the time they reached Chicago, the Australian manager had fled with the meager takings and the players were broke and abandoned.76 They scraped together cash for a final treat, watching Chicago entertain the visiting Orioles. They were warmly greeted by both teams after the game, including by Orioles infielder Joe Quinn, who they were astonished to learn was a native of Queensland and who the Australian Argus reported was “anxious for news from home.”77 Quinn’s exploits had never reached the Australian media or his playing counterparts “Down Under,” and this encounter was the only mention of Quinn in any Australian broadsheet of the era.

In early 1898, Joe Quinn was traded back to St. Louis to rejoin the hapless Browns, around the time the bankrupt club was bought by Cleveland street-car magnates Frank and Matthew Robison, who also owned the Cleveland franchise. Syndicate baseball — two clubs with one owner — is now illegal in professional baseball. But in the nineteenth century, it was common, and nowhere was it more disastrous than Cleveland in 1899. The Robisons dispatched Cleveland stars including pitcher Cy Young and .400 hitter Jesse Burkett to St. Louis to create a southern super-team, and made only an indifferent attempt to restock the Spiders with washed-up veterans and unblooded youngsters from the Browns.

The tone for the Cleveland Spiders’ season was set from the first game, which, cruelly, was scheduled against St. Louis in the Robisons’ new southern stronghold. 15,000 fans cheered the Browns as they stamped out their northern brothers, 10-1.78 Cy Young was on the mound — he would win 26 games in 1899, more than his former team managed for the season. The Spiders then proceeded to set new records for futility in almost every aspect of the game, and their fans deserted them in droves. Lave Cross, perhaps the only good-quality player the Robisons had left in Cleveland, managed the team for the first 38 games of the 1899 season, winning just eight; his performances at third base, however, were good enough to earn him a ticket to St. Louis. Who better qualified to take over the rag-tag bunch than Joe Quinn?

One facetious report suggested Cleveland had the proper manager in Quinn: “a corpse in charge of an undertaker.”79 But the 36-year-old second baseman hauled himself up to his best season in five years, batting .281 and fielding at the top of the National League at second base.80 The Washington Times wrote:

“He is batting and fielding as well as he ever did. If not better. He is a credit to the profession, and the game would be better with more of his kind.” 81

The Spiders did manage one hurrah for their long-suffering fans, whose average attendance was just 100 per game. On July 1, Cleveland defeated Boston 10-9, coming from 7-0 down at the start of the ninth inning. With the score tied in the 11th inning, Quinn stole second and crossed the plate with the game winning run.82 It was sweet but short-lived: the Spiders then lost 14 games in a row.83

The Spiders split their July 18 doubleheader with Washington, Quinn putting in what the Spalding Base Ball Guide of 1899 described as “the fielding performance of the season,” making eight putouts and 14 assists without an error.84 But his miserable troops could not follow suit: between August 25 and season’s end, Cleveland won just one game and lost 40. They closed out the season the way they had started — dismally, thrashed by Cincinnati, who had already beaten them 14 times that season.

Joe Quinn was the last manager of the Cleveland Spiders, whose 20-134 record remains the worst in major league baseball history. The valiant Quinn led the team in batting at .286, and led the league in fielding at second base (.962), committing just 31 errors in 147 games. And teams continued to vie for his services. In 1900, Quinn had another stint in St. Louis of just 24 games; he then played 74 games in Cincinnati, where he made his final appearance in the National League in October 1900.85

Quinn appeared in the inaugural season of the American League with Washington in 1901. But the mediocre play of the Senators was too much, and Quinn sought his release in July.86 It was the only time in his 17-year career that he purposely turned his back on a club.

But in 1902, an invitation to play back in minor-league Des Moines was more than he could resist. After the 1902 season, the team actually changed its moniker from the Midgets to the Undertakers to honor their 40-year-old captain, who had been the Western League’s leading second baseman for the year.87 Quinn closed the book on his professional baseball career with the Undertakers in September 1903, with five championships on his résumé.

By 1920, 58-year-old Joe Quinn, father of eight, had settled into the simple pleasures of life. In 1895, he had been made a full partner in Thomas McGrath’s undertaking business, and though McGrath had died in 1907, McGrath & Quinn had continued to flourish in their gloomy trade. By 1920, the firm had moved into larger premises on Union Boulevard; three of Quinn’s five sons had also followed him into the business.88 Two of the boys, Joseph Jr. (b. 1893) and Clarence (b. 1894), had been enthusiastic sandlot ball players in St. Louis but had given the game up to work with their father.89 But in 1920, Joe’s fourth son, John Richard — known as “Scotty” — was invited to try out with John McGraw’s New York Giants. Quinn adored the boy, both for his resemblance to his own father and for his passionate love of baseball. Scotty was born in 1897, the year the Orioles won the Temple Cup with McGraw and Joe Quinn sharing duties at third base. And now Scotty had a shot at becoming manager McGraw’s new third baseman.

But in that terrible year, St. Louis was under siege from deadly Spanish influenza. On February 2, 1920, just days before Scotty’s departure for New York, Joe’s daughter Estelle came dashing, hysterical, into the funeral parlor and fetched him home. Scotty was already unconscious. Joe watched his son struggle for life for three days. On February 5, Scotty Quinn died.90 Four of Joe and Mary Ellen Quinn’s babies had been stillborn,91 but this was different: a tragedy of such dreadful proportions that Joe never spoke of his son again.92

The impoverished boy who had once earned a living grubbing in the Iowa zinc mines had become one of St. Louis’ most successful businessmen. But in 1937, life dealt Joe Quinn another blow — the loss of his wife of 51 years when Mary Ellen Quinn died from heart disease.93 Quinn’s own health began to decline. Suffering from myocarditis and the beginnings of dementia, he was hospitalized in February 1940, and never returned to his home at 1389 Union Boulevard. Quinn died on November 12, 1940, aged 77.94 His funeral was arranged by his faithful sons. He was buried in the family plot at Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis beside his wife and his beloved Scotty.95

On May 4, 2013, Quinn was inducted into Baseball Australia’s (virtual) Hall of Fame as an “Australian baseball pioneer…for many more to come.”96 However, accolades were not Joe Quinn’s way. The only monument to his life, still standing in Calvary Cemetery, is appropriately unpretentious: it is marked only “Quinn.”

This biography has been adapted from the full-length book by Rochelle Llewelyn Nicholls, Joe Quinn among the Rowdies: The Life of Baseball’s Honest Australian (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2014).

Notes

1 Queensland Registry of Births Deaths & Marriages. (2015). “Birth Registration: Quinn, Joseph James (Per Quinn, Patrick – Catherine Mcafie)”, Department of Police & Justice, Queensland. [cited July 15, 2001]. Available.

2 From records of the ship Matoaka: “Matoaka [Passenger List]: Online Microfilm of Shipping Lists.” (2012). New South Wales Government State Records. [cited July 7, 2012]. Available from: http://www.records.nsw.gov.au.

3 Vynette Sage (2009). “Enniskillen Workhouse Register: Dec 1845 — July 1847.” Ireland Genealogy Projects. Available from: http://www.igp-web.com/fermanagh/Donated.htm. [cited December 12, 2012].

4 “Telegraph [Passenger List]: Online Microfilm of Shipping Lists.” (2012). New South Wales Government State Records. [cited December 28, 2012]. Available from: http://www.records.nsw.gov.au.

5 Queensland Registry of Births Deaths & Marriages. (2015). “Birth Registration: Quinn, Joseph James (Per Quinn, Patrick – Catherine Mcafie) “ Department of Police & Justice, Queensland. [cited July 15, 2001]. Available.

6 “Australia Birth Index, 1788-1922: Patrick F. Quin.” (2010). Ancestry.com. [cited July 1, 2012]. Available from: www.ancestry.com.

7 “Supreme Court, Brisbane. In the Insolvent Estate of the Moreton Bay Tramway Company,” Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald & General Advertiser (Brisbane, , Queensland). February 17, 1863, 3.

8 “Municipal Council,” Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald & General Advertiser (Brisbane). July 12, 1864, 3.

9 “Opening of the First Railway in Queensland (from Our Special Reporter),” The Brisbane Courier, August 1, 1865, 2-3.

10 Maree Murray, “Children’s Work in Rural New South Wales in the 1870s,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 79 (3-4), 1993: 226-244.

11 “Distress in the Agricultural Districts,” The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales), March 9, 1864, 5.

12 The logs of 1872 passenger ships between the USA and Australia did not record the names of steerage passengers, but the year of the Quinns’ arrival in the United States, 1872, is recorded in the 1900 United States census: Joseph J. Quinn (image no. 00620): “United States Census: City of St. Louis, Missouri – Division of St. Louis City.” (1900). United States Census Office. [cited November 11, 2012]. Available from: www.familysearch.org.

13 “Patrick Quinn Is Dead,” Dubuque Telegraph-Herald (Dubuque, Iowa), April 12, 1902: 3.

14 Marble’s Dubuque City Directory (Dubuque, Iowa: Chas. A. Marble, 1881).

15 William Mott Steuart, Special Report: Mines and Quarries (Washington: Department of Commerce and Labor — Bureau of the Census, 1905), 450.

16 Joe Clark, A History of Australian Baseball: Time and Game ( Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 12.

17 Dick Farrington, “Half a Century through Joe Quinn’s Eyes: Union Star Recalls Birth of ‘the Sporting News’”, The Sporting News (St. Louis, Missouri). May 21, 1936: 9B.

18 Ibid.

19 Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press. 1960), 102.

20 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Major League Baseball (Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 178.

21 Bill Borst, Baseball through a Knothole: A St. Louis History (St. Louis: Krank Press, 1980), 34.

22 Farrington, “Half a Century through Joe Quinn’s Eyes”

23 “Notes and Comments,” The Sporting Life (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), April 22, 1885: 7.

24 Farrington, “Half a Century through Joe Quinn’s Eyes”

25 “Washington Whispers,” The Sporting Life, September 6, 1890: 13.

26 “Sporting: The Altoonas Again Defeated by Our Union Club,” The Republican (St. Louis, Missouri), April 27, 1884: 3.

27 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 24-31.

28 “From the Mound City,” The Sporting Life, March 24, 1886: 8.

29 “Joe Quinn,” Indianapolis Herald, June 15, 1887: 3.

30 Rochelle Llewelyn Nicholls, Joe Quinn among the Rowdies: The Life of Baseball’s Honest Australian (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2014), 61-75.

31 “Duluth’s New Manager,” The Sporting Life, August 31, 1887: 7.

32 “Sports, Limited,” Saint Paul Daily Globe (St. Paul, Minnesota), February 8, 1888: 5.

33 Joseph M. O’Toole, “My God, What a Life!” (St. Louis: O’Toole, 1981), 13.

34 Seymour and Mills, Baseball: The Early Years, 332-333.

35 Robert G. Mayer, Embalming: History, Theory, and Practice, Fifth Edition (New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2011), 492.

36 Farrington, “Half a Century through Joe Quinn’s Eyes.”

37 “St. Louis Screed,” The Sporting Life, October 27, 1886: 2.

38 “From St. Louis,” The Sporting Life, October 6, 1886: 4.

39 “A Talk with Joe Quinn,” The Sporting Life, November 23, 1887: 3.

40 “Sporting Notes,” Boston Globe, January 6, 1888: 6.

41 He had made his professional debut in 1872, the year Quinn arrived in America, with the Brooklyn Atlantics. Kathy Torres, “Jack Burdock,” SABR Baseball Biography Project. Society for American Baseball Research. [cited May 5, 2013]. Available from: http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/834f6239.

42 “Hunting for Talent,” Saint Paul Daily Globe, August 12, 1888: 6.

43 “The price of his release has not been made public, but it is well known that it was not less than $4,000. The Boston management is to be praised for its liberality and perseverance in bringing to a close this negotiation, which ranks with those that secured Clarkson and Kelly.” From: “Boston’s Latest: Joe Quinn, Their New Second Baseman, and His Record,” The Wichita Daily Eagle (Wichita, Kansas), October 16, 1888, 7.

44 “Won by a Home-Run Hit,” New York Times, August 30, 1888: 7.

45 “Baseball Stories by Joe Quinn; Outlook for the Cardinals in 1906,” St. Louis Republic (St. Louis, Missouri), December 10, 1905: 6.

46 Peter M. Gordon, “King Kelly,” SABR Baseball Biography Project. Society for American Baseball Research. [cited June 20, 2013]. Available from: http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ffc40dac.

47 “Joe Quinn Gets a Bat,” Boston Globe, September 13, 1889: 8.

48 “Joe Quinn in the Outfield,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1888: 5.

49 Daniel M. Pearson, Baseball in 1889: Players vs. Owners (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1993).

50 Dean A. Sullivan, Early Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1825-1908. (Ann Arbor, Michigan.: The University of Michigan Press, 1995), 197.

51 “The Great Scheme: The Plans of the Brotherhood Given in Detail,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1889: 3.

52 David Stevens, Baseball’s Radical for All Seasons: A Biography of John Montgomery Ward (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1998), 91.

53 Alfred H. Spink, The National Game, (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000 — reprint), 28-29.

54 “News, Notes and Comment,” The Sporting Life, December 11, 1890: 5.

55 “Joe Quinn, the Champion Second Baseman,” Boston Globe, October 11, 1890: 7.

56 J. Thomas Hetrick, Chris Von Der Ahe and the St. Louis Browns (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow, 1999).

57 “J. Quinn,” The Sporting News, February 11, 1893: 1.

58 St. Louis City Directory 1893-1894: “United States City Directories, 1882-1901. Saint Louis, Mo. [Microform].” (1990). Research Publications: Woodbridge, Connecticut.

59 “St. Louis Siftings — the Dedication of a New Park a Social Event,” The Sporting Life, May 6, 1893: 3.

60 “The Browns in a Rather Crippled Condition,” The Sporting Life. July 13, 1995: 10.

61 “Obituary: Joe Quinn,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1940: 8.

62 The Sporting Life reported, “Capt. Joe Quinn has sold his livery stable business. Joe has a nice competence, and is of that steady, thrifty character that gives him the reputation of being one of the really substantial members of the profession”: “St. Louis Siftings – Rumors as to the Make-up of the ’94 Team,” The Sporting Life, October 21, 1894: 5.

63 Farrington, “Half a Century through Joe Quinn’s Eyes.”

64 “St. Louis Siftings — Ready for the Great Fight of 1894,” The Sporting Life, April 21, 1894: 6.

65 “Games Played July 4,” The Sporting Life, July 14, 1894: 3.

66 “St. Louis Siftings,” The Sporting Life, August 4, 1894: 4.

67 The Dead March is part of a three-act oratorio, “Saul,” composed by George Frederic Handel in 1738. See also: “Baseball: Personal,” The Sporting Life, June 8, 1895: 4.

68 “League-Association,” The Sporting Life, July 6, 1895: 3.

69 “Obituary: Joe Quinn.”

70 “St. Louis Sayings,” The Sporting Life, July 27, 1895: 10.

71 “The Browns in a State of Demoralization,” The Sporting Life, August 10, 1895, 11.

72 J. Thomas Hetrick, Misfits! The Cleveland Spiders in 1899: A Day-by-Day Narrative of Baseball Futility. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1991).

73 “Joe Quinn Released: Der Cherman Pand Must Be Playing Madhouse Airs!,” New York World, July 1, 1896: 3.

74 The .698 win-loss percentage of the 1896 Orioles bettered their 1894 effort by 0.003; the team won the National League pennant in both years, in addition to their 1895 triumph. The franchise was born in 1882 and spent its first nine seasons in the American Association before transferring to the National League. In 1899, the team franchise and that of the Brooklyn Superbas were co-owned by Baltimore owner Harry Van der Horst and Ned Hanlon — most of the star Baltimore players were shipped to Brooklyn and the denuded Orioles finished only fourth. They were one of four teams dropped by the National League as it downsized to eight teams for the 1900 season. Mark L. Armour and Daniel R. Levitt, Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got That Way. (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2004), 12-17.

75 W.J. Monaghan, “One of Baseball’s Great,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 26, 1933: 6,14.

76 Clark, A History of Australian Baseball, 35.

77 Twister, “The Australian Base-Ballers,” The Argus (Melbourne, Victoria), July 23, 1897: 5.

78 “The Farce Has Begun,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 16, 1899: 1.

79 “Gossip of the Diamond,” Evening Times (Washington, DC), August 12, 1899: 6.

80 “Cleveland Chatter — Cross’ Men Broke Even with the Eastern Clubs,” The Sporting Life, June 3, 1899: 4.

81 “Gossip of the Diamond,” The Times (Washington, DC), July 19, 1899: 6.

82 “A Revival of Interest in the Forest City,” The Sporting Life, July 8, 1899: 5.

83 “Games Played July 17,” The Sporting Life, July 22, 1899: 3.

84 Henry Chadwick, Spalding Official Base Ball Guide for 1899 (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1900), 145.

85 “St. Louis Sad over the Persistent Bad Luck of the Cardinals,” The Sporting Life, June 16, 1900: 5; “The Passing of Quinn,” The Sporting Life, September 29, 1900: 7.

86 “Notes About the Big and Little Ball Tossers,” St. Paul Globe, April 7, 1902: 5.

87 Dennis Pajot, Baseball’s Heartland War, 1902-1903: The Western League and American Association Vie for Turf, Players and Profits (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2011), 199.

88 “United States Census: City of St. Louis, Missouri – Division of St. Louis City.” (1920). United States Census Office. [cited November 12, 2012]. Available from: www.familysearch.org.

89 Farrington, “Half a Century through Joe Quinn’s Eyes.”

90 John R. Quinn: “Missouri Death Certificates, 1910-1962.” (2013). Missouri Digital Heritage. [cited April 28, 2013]. Available from: http://www.sos.mo.gov/archives/resources/deathcertificates/advanced.asp.

91 “Section and Lot Report for Calvary Cemetery,” Catholic Cemeteries of the Archdiocese of St. Louis, 1988. [cited May 17, 2000]. Available from: http://archstl.org/cemeteries/content/view/91/233/.

92 Tom Hesemann, “Re: Joe Quinn – Australian Born Major League Ball Player,” E-mail to Rochelle Nicholls. April 20, 2000.

93 Mary Ellen Quinn: “Missouri Death Certificates, 1910-1962.” (2013). Missour Digital Heritage. [cited April 28, 2013]. Available from: http://www.sos.mo.gov/archives/resources/deathcertificates/advanced.asp. and “Death Notice – Mary E. Quinn (Nee Mcgrath).”. St. Louis Globe-Democrat. December 14, 1937: 5C.

94 “Missouri Death Certificates, 1910-1962.” (2013). Missouri Digital Heritage. [cited April 28, 2013]. Available from: http://www.sos.mo.gov/archives/resources/deathcertificates/advanced.asp.

95 “Obituary: Joe Quinn.”

96 2012/13 Baseball Australia Annual Report (Gold Coast, Australia: Baseball Australia, 2013), 59.

Full Name

Joseph James Quinn

Born

December 24, 1862 at Ipswich, Queensland (Australia)

Died

November 12, 1940 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.