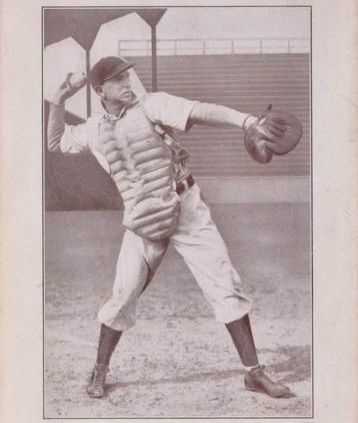

Johnny Kling

Arguably one of the most overlooked star players of the Dead Ball Era, catcher Johnny Kling was a key part of the great Chicago Cubs Dynasty of 1906-10. When his baseball career was over, Kling returned to his hometown of Kansas City, Missouri where he enjoyed a successful business career. A modest man, Kling never thought anyone would be interested in his accomplishments as a player once he retired.

Arguably one of the most overlooked star players of the Dead Ball Era, catcher Johnny Kling was a key part of the great Chicago Cubs Dynasty of 1906-10. When his baseball career was over, Kling returned to his hometown of Kansas City, Missouri where he enjoyed a successful business career. A modest man, Kling never thought anyone would be interested in his accomplishments as a player once he retired.

John Kling fell in love with the game at an early age, but he was required to help his father with the family bakery business. His job was to drive a horse drawn wagon and deliver bread to waiting customers. Every morning, the clang of the family alarm started John on his route, making deliveries. The story is told that the route never grew in numbers and the elder Kling started to learn why. An irate housewife informed the bakery proprietor she would take bread from a competitor since the Kling wagon never reached her house on time.

One morning, Kling’s father started out on the trail of Johnny and found the horse meandering down the road. Where was Johnny? A great deal of noise over in a corner field, where a baseball game was in progress, revealed the truth about the undelivered bread. Did the elder Kling use a paddle on youthful Johnny? Only history knows.

Those good old corner lot days were soon over. In 1890, at age 14, he pitched for the Haverlys and led the team to an amateur league championship. At age 15 Johnny got on a team that had real honest to goodness uniforms. It was the SIBER meat market team, sponsored by John Siber, a butcher. Two years later he joined the Schmeltzers, during the two-year term with the team he pitched, played first base and managed. In 1895 he was given a tryout with St. Louis but was not given a contract because he was too small.

In 1896 he joined Houston of the Texas League and in 1897 he was with the Emporia team. His size again played a role in 1898, when Rockford dropped him because he was too small. He then went back to the Schmeltzers. When he joined the team, they made him a catcher, where he was destined to shine brilliantly in the annals of the national pastime.

In 1899 he went on a barnstorming trip with Kansas City of the Western League. While at a game in Atchison he was noticed by manager Byron McKibben of the St. Joseph club. In 1900 he began to play with St. Joseph, but in late summer Ted Sullivan found him and signed him for the Chicago Colts. He made his major league debut in September 1900 with the team, he played fifteen games and hit .294 earning a chance to return to the major leagues. Sullivan, ironically was a boyhood friend of White Sox owner Charles Comiskey.

In 1901 Kling shared catching duties with Mike Kahoe and Frank Chance. He appeared in 69 games behind the plate, hitting a respectable .273. It was clear that manager Tom Loftus‘ catcher, Chance, had difficulty in handling foul tips. In 1902 new Cub skipper Frank Selee decided that Chance would be his permanent first baseman and Kling his full time catcher. The addition of Joe Tinker at shortstop established the nucleus of a team that would terrorize the National League later in the decade. Kling responded to full time duties by leading the league’s catchers in putouts, assists and double plays. At bat in 1902 he hit .289 and led the Chicago Nationals in RBI with 59, while batting eighth in the order.

During the Dead Ball Era a strong defensive catcher was a key component of any great team, due to the emphasis on bunting and base stealing. Kling was the dominant defensive catcher during the first ten years of the twentieth century. From 1902 through 1908 he led the National League in fielding percentage twice, putouts six times, and assists and double plays once each. Cub pitcher Ed Reulbach called Kling one of the greatest catchers to ever wear a mask. In at notable game on June 21, 1907 he threw out all four Cardinal runners who tried to steal second, and in the World Series he gunned down 5 of 11 Tiger runners, holding base stealing champion Ty Cobb to no stolen bases.

As his 1902 figures showed, he was no easy out at bat and was a strong contributor to the Cub offense. In 1906 he hit .312 and batted in 46 runs on a Cubs team that the most games (116) in history. Kling had a career batting average of .272.

His contemporaries, team mates and opponents alike, marveled at his ability to defend, handle pitchers and take part in the psychological warfare which was baseball in the early twentieth century. Johnny Evers claimed Kling could tell pitchers what their best stuff was during warm-ups. He kept up a steady string of chatter earning him the nickname ‘Noisy.’ Evers praised Kling for his ability to work umpires on balls and strikes, yet Kling avoided antagonizing the men in blue, even warning them if an unusual play or pitch was coming.

In an era where many players could be best described as social outcasts, Kling was different. He did not smoke, chew or drink. His grandchildren say he was very kind and loved spending time with them. His eldest daughter was mascot of the Braves during the time her Daddy was manager. Some insight into Kling’s character comes from the biography of former baseball commissioner Ford Frick. In Games, Asterisks and People, Frick describes attending an exhibition game involving the Cubs in 1907 in Kendallville, Indiana. As the Cubs were walking to the ballpark, Kling asked the young Frick if he wanted to go to the game. When Frick said yes, Kling had the future baseball tsar carry his shoes. Once at the game Frick was allowed to sit near the bench and see his Cub heroes in action and hear their bench talk between innings.

Kling’s difference from other Dead Ball Era players extended to his approach to life. Baseball was a job that opened doors for other opportunities. In other words, he was not a baseball lifer. He had other skills to fall back on, thus his yearly contract talks with Cub owner Charles Murphy often resembled a game of chicken, more than a negotiation.

Following the Cubs’ championship year in 1908, Kling won the world pocket billiards championship. He then invested about $50,000 in a billiard emporium in Kansas City, informed Murphy of the investment and requested an indefinite leave of absence. Murphy granted this in writing and Kling promised that if he could subsequently arrange his affairs so that he could leave his business in the hands of others, he would join the team. The arrangement was on the best of terms according to the investigative report by the National Commission in 1910, when Kling had applied for reinstatement into baseball. This story, as told in the Commission’s report, varies with news articles that described Kling as a holdout, unable to negotiate a satisfactory contract with Murphy. But those statements were not true. Kling had a valid contract for 1907, ’08 and ’09 as pointed out in the Commission’s report. And in spite of receiving an indefinite leave from Murphy, Kling was held to be in violation of his contract for not playing. He was fined $700 and allowed to return to the Chicago team. He was given a $4500 salary, the same as in 1908.

The 1909 hiatus was costly for Kling and the Cubs. The year marked the first since 1906 that the Cubs did not win the pennant, they finished second to the Pirates. As for Kling, he failed to defend his billiards championship.

Kling always maintained that players should learn a lesson from him and stay in the game until they were ready to retire. Despite his clean living habits, Kling found it hard to regain the skills that he had just a few years previous. In 1911 he was traded to the Boston Braves, some claimed as punishment for his holdout and poor performance against Philadelphia in the 1910 World Series. He played and managed for the Braves in 1912. He hit .317, but the team finished dead last at 52-101. His playing career ended in 1913 in Cincinnati.

Upon retirement Kling returned to his native Kansas City where he continued on with a career in real estate, one he had started while playing baseball. He became a successful businessman. He had a knack for developing real estate and amassing wealth. Kling had a compassionate side as well, and would quickly make out a check when a friend was in need. During World War I, he volunteered his services to the military and taught and coached baseball at Camp Funston, Kansas. Kling was a doting parent and his family never wanted for the basic comforts, even during the height of the Great Depression.

In 1933 he bought the Kansas City Blues and promptly eliminated segregated seating at Muehlebach Field, which happened to also be the home of the Monarchs of the Negro Leagues. This policy remained in effect until Kling sold the club in 1937 to Col. Jacob Ruppert of the New York Yankees.

Kling was a private man who preferred life out of the spotlight. We do know he cared little about what others thought or said about him. Some historians claim he was among the first Jewish baseball stars, but such an assertion is still a matter for debate. In a February 12, 1969 letter, Kling’s wife said he was baptized Lutheran. In a December 2, 1948, letter, she claimed “he was baptized in the Baptist Church.” Nobody seems to have questioned the contradiction nor her motivation for making these statements. Kling’s grandson, also named John Kling, recently claimed that his grandfather was definitely Jewish. Membership records for B’nai Jehudah Temple, in Kansas City, Missouri, of close family members, in addition to other records, supports the Jewish heritage issue. Nevertheless, the issue continues to be matter for debate.

Who should one believe? Either way, Kling cared little about what people said about his religion. It was something he chose not to discuss. His focus was on the task before him. And overall, he was successful in whatever venture he took on, be it baseball, business or desegregating seating in the Kansas City ballpark. He was a man with ideas who met challenges head on. He was a man with lofty ideals, a man before his time.

Sources

Dave Anderson and Gil Bogan have had a number of conversations about Kling. Much of the material for this biography was from Dave’s book More than Merkle and Gil’s upcoming book on Johnny Kling’s life.

Full Name

John Kling

Born

November 13, 1875 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

Died

January 31, 1947 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.