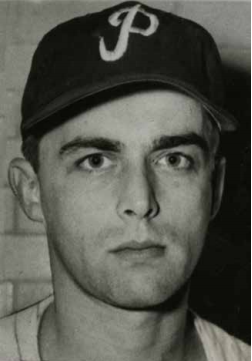

Ken Johnson

On September 27, 1947, a soft-spoken 24-year-old left-handed pitcher from Kansas toed the rubber at Wrigley Field preparing to make his first major-league start for the St. Louis Cardinals against the Chicago Cubs.1 The National League pennant race was over for the season and the Cardinals would finish second to the Brooklyn Dodgers. Eddie Dyer, the manager, decided to rest many of his starters and take a look at his younger players. Dyer basically informed the lefty, Ken Johnson, that he was not going to win.2 “Don’t worry,” Dyer said. “I just want you to see what it is like up here.”3

On September 27, 1947, a soft-spoken 24-year-old left-handed pitcher from Kansas toed the rubber at Wrigley Field preparing to make his first major-league start for the St. Louis Cardinals against the Chicago Cubs.1 The National League pennant race was over for the season and the Cardinals would finish second to the Brooklyn Dodgers. Eddie Dyer, the manager, decided to rest many of his starters and take a look at his younger players. Dyer basically informed the lefty, Ken Johnson, that he was not going to win.2 “Don’t worry,” Dyer said. “I just want you to see what it is like up here.”3

Dyer told Johnson not to worry if he gave up five or six runs. This seemed to relax the young pitcher, and that day Kenneth Wandersee Johnson pitched a masterpiece. During the first seven innings, he faced 23 batters and held the Cubs hitless; the only baserunners were Andy Pafko, who drew a walk in the second inning, and Cliff Aberson, who walked in the seventh. (Aberson was erased when Pafko hit into a double play.)

In the eighth inning, with a 3-0 lead, Johnson hit Ray Mack with a pitch, Bob Sturgeon reached on an error, and Don Johnson walked to load the bases. Johnson then surrendered a run-scoring single to Eddie Waitkus. The Cubs’ only hit resulted in their only run of the game.

Johnson began to tighten up in the ninth inning, especially when slugger Bill Nicholson strode to the plate with two outs. Eddie Dyer bounced out of the dugout to share some encouraging words for his young left-handed pitcher:

“You get your good curve over, and this big slob couldn’t hit you with two bats. Just throw the curve with something on it.”4

Johnson broke off a curve, and Nicholson could only bow for strike one. He followed it up with another curve for strike two. Johnson threw the hook again, and Nicholson flied out to right field. Johnson had won his first big-league game! He even capped his remarkable day by getting two hits in four at-bats.

Only twice in major-league baseball had a rookie pitcher thrown a no-hitter, both times in the 19th century: Theodore Breitenstein in 1891 and Charles L. Jones in 1892. Rookie Johnson nearly matched them, carrying a no-hitter into the eighth inning of his first start.

Kenneth Wandersee Johnson was born in Topeka, Kansas, on January 14, 1923, to Alvin and Rhea Johnson. Alvin worked at the Topeka Canning Company. Kenneth graduated from Topeka High School and in 1941 was spotted as an 18-year-old playing American Legion ball in Topeka by Branch Rickey Jr. of the Cardinals organization. According to Johnson, he convinced Rickey that he needed money to attend the University of Kansas and received a $5,000 signing bonus. Johnson said that after getting that bonus, “I thought that there wasn’t any money left in St. Louis.”5

Johnson was assigned to the Asheville Tourists of the Class-B Piedmont League, where he posted a 1-8 record with a 5.54 earned-run average. Exhibiting the control issues that would plague him his entire career, he walked 61 batters in 65 innings. The following year, also with Asheville, he was 8-8 and lowered his ERA to 4.32 but walked 104 in 123 innings. Then came World War II.

By 1943, Johnson was an officer in the US Army, serving in the Pacific.

After the war Johnson pitched 11 games for the Rochester Red Wings in 1946 and went 1-4 with a 5.02 earned-run average and 44 walks in 43 innings. He began 1947 with the Triple-A Columbus Red Birds but wildness continued to plague him and the Cardinals sent him down to Omaha of the Class-A Western League, where he posted a 6-2 record with a 2.40 ERA, good enough to earn him a September callup, and allow him to make his memorable debut against the Cubs. After the season, on December 11, 1947, Johnson and Barbara Burns were married.

Johnson opened the 1948 season with the Cardinals but saw little action and was sent to Rochester, where he was 6-9 with the Red Wings. He returned to the Cardinals near the end of July and appeared in nine games (four starts) and had a 2-4 record for the season with a 4.76 ERA. He was 0-1 in 1949, appearing in 14 games, but was not used after June because of his disappointing 6.42 ERA and continuing control problems. (Though not used after June, he remained on the Cardinals roster the entire season.)

After pitching in parts of four seasons for the Cardinals (1947-50), Johnson was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies on April 27, 1950, in exchange for Johnny Blatnik, a little-used outfielder. Phillies manager Eddie Sawyer saw Johnson as an investment in the future.

Sawyer called Johnson “a Cardinal stepchild for several years” who “had been booted in and out of the ash can on several occasions,” and “wasn’t even considered good enough for relief duty.”6 He thought Johnson had one of the best curveballs he’d ever seen, although he had trouble throwing for strikes.7

Used as a spot starter, Johnson won the first four games he pitched for the Phillies. Because of his wildness, coach Benny Bengough took Johnson under his wing and worked with him in the bullpen each day. The Phillies felt that Johnson’s pitching had at times been astounding considering how infrequently St. Louis used him. Before his first Phillies start, on May 3, Sawyer told catcher Ken Silvestri to try to get Johnson to throw the ball over the center of the plate to avoid walks, even at the expense of giving up hits.8 The plan worked, and Johnson beat the Cubs, 5-2, walking only two in eight innings but giving up 12 hits. He eschewed his curveball, using fastballs almost exclusively.

Five days later, on May 8, Johnson beat the Cincinnati Reds, 6-5, mixing the curve and fastball in six innings of work. He didn’t record a strikeout in either of his first two starts. He defeated the Reds again, 5-4, on May 17 in a complete game. After a couple of rocky spot starts, Johnson was used sparingly out of the bullpen and was out of action for a while after being hit on his throwing hand while pitching batting practice.9

Sawyer decided to give Johnson another start on August 7 against the Cardinals. Sawyer felt Johnson performed better when he didn’t know he was pitching. On this night, he had spent the day at the hospital because his wife was giving birth. He arrived at the ballpark just before game time and told the team his wife had just had a baby girl and everything was fine. Sawyer said, “Good. You’re pitching.”10

That night Johnson exacted revenge on his old team, showing the form they had hoped for, with a two-hit, 9-0 shutout. He struck out six and walked six. He started shakily, giving up a single to Stan Musial and then walking two to load the bases with two outs, but then got Nippy Jones to fly to center. He walked two more in the second, before finding his groove and walking only two more the rest of the way. That performance earned Johnson a start on August 13 and he suffered his lone loss, 2-0 to the New York Giants’ Jim Hearn. Johnson pitched a complete game, threw mainly breaking pitches, and six hits but walked seven.

Johnson made only two more pitching appearances and finished the season with a 4-1 record. He started nine games with three complete games, and worked in relief five times, finishing with a 4.01 earned-run average in 60⅔ innings.

Johnson did not pitch against the Yankees during the World Series. He did get in as a pinch-runner for Dick Sisler and scored in the ninth inning of the fourth and final game.

Before the 1951 season, the question arose: Who would replace Curt Simmons while Simmons served in the Army? Although the Phillies felt that Johnson was loaded with natural stuff, he had never shown the control or poise necessary to serve as a replacement for Simmons.11

A well Johnson owned in Kansas struck oil during spring training in 1951. Johnson decided that if his monthly income from the well reached $1,000, he would retire from baseball.12

On Johnson’s player questionnaire completed for the Hall of Fame in 1963, he answered “doubtful” to the question of whether he would play baseball if he had to do it over again. Author Paul Rogers interviewed Johnson around 1995 and Johnson said he felt he’d squandered his talent in baseball and been a failure. He thought he’d been successful in life after baseball but mostly tried to forget his baseball career. He was the only member of the Whiz Kids who didn’t go to the team’s 1975 reunion.13

Johnson flashed his brilliant potential during the 1951 season with three shutouts but finished with a 5-8 record and a 4.57 ERA. During spring training in 1952 he was placed on waivers and was claimed by the Detroit Tigers. In nine games (one start) he pitched 11⅓ innings for Detroit, walking 11. He started a game for the Tigers on July 15 but was pulled in the third inning after walking five batters. At age 29, it was his last major-league appearance. The Tigers assigned Johnson to Buffalo, he where started seven games, won three games, all shutouts, lost two, and had a 3.38 ERA. His major-league record was 12-14 in 74 games with a 4.58 ERA. He walked 195 batters in 269⅓ total innings, struck out 147, and gave up 251 hits.

Not yet prepared to go home and live off his oil-well earnings, Johnson hung around in Triple-A baseball for four more years. Control problems still bothered him, but he won 12 games for Buffalo in 1953, 14 for the Bisons in 1954, 14 for Toronto in 1955, and 8 for the Maple Leafs in 1956. After the ’56 season, Johnson retired from baseball at the age of 33.

After baseball, Johnson became an insurance executive in Wichita, retiring as a vice president for IMA Financial Group. He died on April 6, 2004, at the age of 81. After Kenneth Wandersee Johnson’s MLB debut it looked as if he was headed for a Hall of Fame career, but the only thing that would go to Cooperstown was the curveball he taught to Robin Roberts.

This biography appears in “The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2018), edited by C. Paul Rogers III and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources reflected in the notes, the author also consulted:

Orodenker, Richard. The Phillies Reader (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005).

Paxton, Harry T. The Whiz Kids (New York: David McKay Company, 1950).

The Phillies 1951 Official Yearbook, 1951.

Notes

1 Johnson had made his major-league debut on September 18 in relief when he pitched a scoreless ninth inning in a 6-2 Cardinals loss to the Boston Braves.

2 “Hats Off,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1947: 17.

3 The Sporting News, March 24, 1948: 4.

4 Ibid.

5 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 222.

6 The Sporting News, August 23, 1950: 8.

7 Roberts and Rogers, 246.

8 Roberts and Rogers, 223.

9 Roberts and Rogers, 246.

10 Ibid.

11 The Sporting News, January 10, 1950: 10.

12 “Ken Johnson Strikes Oil; He talks of Retirement,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1951: 10.

13 Ken Johnson player questionnaire, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Full Name

Kenneth Wandersee Johnson

Born

January 14, 1923 at Topeka, KS (USA)

Died

April 6, 2004 at Wichita, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.