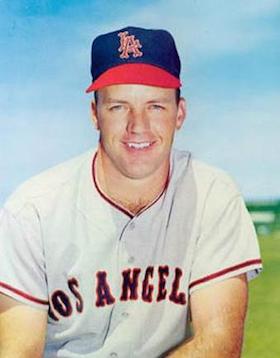

Lee Thomas

After being stuck in the New York Yankees minor-league system for seven seasons, Lee Thomas spent 1961 through 1968 as a big-league player. The first baseman/outfielder was an All-Star in his best year, 1962 – but his finest day came in the final month of his rookie season. On September 5, 1961, Thomas (then with the Los Angeles Angels) had what remains one of the greatest doubleheaders in baseball history. He was a perfect 5-for-5 in the opener and 4-for-6 in the nightcap, when he slugged three home runs, including a grand slam, and drove in eight runners. His nine hits for the twin bill tied a major-league record that, as of 2016, he still shared with eight others.

After being stuck in the New York Yankees minor-league system for seven seasons, Lee Thomas spent 1961 through 1968 as a big-league player. The first baseman/outfielder was an All-Star in his best year, 1962 – but his finest day came in the final month of his rookie season. On September 5, 1961, Thomas (then with the Los Angeles Angels) had what remains one of the greatest doubleheaders in baseball history. He was a perfect 5-for-5 in the opener and 4-for-6 in the nightcap, when he slugged three home runs, including a grand slam, and drove in eight runners. His nine hits for the twin bill tied a major-league record that, as of 2016, he still shared with eight others.

However, Thomas made his greatest contributions to the game after he hung up his spikes, primarily in the front offices of two National League teams. As director of player development from 1980-88 with the St. Louis Cardinals, he helped build a club that won a World Series (1982) and two other NL pennants (1985, 1987). Later, as general manager with the Philadelphia Phillies (1988-97), he earned recognition as The Sporting News Major League Executive of the Year in 1993 for his work building the pennant winner that year. Along with Al Rosen and Johnny Murphy, he is one of only three men thus far to win that award after being an All-Star player.

Born in Peoria, Illinois, on February 4, 1936, James Leroy Thomas says he never knew his biological father, John Leonard Thomas.1 He was raised by his mother, Dorothy (Hutchison) Johanson (1919-96), and his stepfather, Hildor E. Johanson (1908-91), who married his mother when Thomas was still a boy. Johanson served three years in the U.S. Army during World War II, when he rose to the rank of staff sergeant. He then moved with Thomas and Dorothy to St. Louis, where he worked as a mechanic.

Thomas has nearly always been referred to by his middle name, although he preferred the nickname “Lee” because he detested “Leroy.” Until 1963, when he told a reporter that, the press often identified him as “Leroy.” After that, writers almost universally began to use “Lee.”2

As a boy, Thomas pursued sports with a passion. At Beaumont High School in St. Louis, from which he graduated in 1954, he lettered in football, basketball, and baseball, excelling in all three. As football team co-captain, he played halfback and fullback until he suffered an injury early in his senior year. One sportswriter called him “the TD kid,” so dogged was Thomas in his pursuit of the goal line.3 As a forward in basketball, during his senior year he finished fifth in voting for the St. Louis sectional prep player of the year. The award was co-sponsored by St. Louis radio station KXOK and the YMCA.4

In baseball, splitting time between first base and the outfield, Thomas hit .370 as a junior and .580 in his senior year, earning an outfield spot on the conference All-Star team in the latter year.5 Although he was a lefty batter, he threw righty. When fully grown, he was 6-foot-2 and 195 pounds.

While Thomas was in high school, Yankee scout Lou Maguolo started following him. Shortly after graduation, on June 19, 1954, Thomas signed for a bonus of something less than $4,000.6 The team sent him to the Owensboro (Kentucky) Oilers in the Class D KITTY League to start his professional career. In his first game with the Oilers five days after signing, he had four hits in a 13-12 victory over the Fulton (Kentucky) Lookouts.7

Thomas went on to have a solid minor league career, advancing steadily through the Yankee organization for the first few seasons, moving up to Birmingham of the Class A Eastern League by 1956. He spent the next two seasons there, making the league All-Star team in 1958 when he finished third in the league with 17 home runs, while hitting .281.

When the Yankees assigned him to Birmingham for yet another season, however, Thomas—whose reputation for temper won him the nickname “Mad Dog”—walked away from spring training. Unfortunately, he was trapped behind a formidable list of All-Star and Gold Glove outfielders and first basemen on the big club, including Mickey Mantle, Bill Skowron, and Norm Siebern.8 Moreover, his frustration also smoldered because he believed the team was promoting less talented players ahead of him.9

Convinced to return, however, he had an even stronger season for Birmingham in 1959, hitting .304 and finishing fourth in home runs (24) and second in RBIs (122), earning a repeat appearance on the Eastern League All-Star team.

On the basis of this performance, the New York Times tabbed Thomas as a rookie to watch going into spring training for 1960.10 Despite that, he ended up back in the minor leagues that season, initially at Amarillo in the Double-A Texas League. In 61 games there, he batted .390 with 17 home runs and 76 RBIs and wound up on his third minor-league All-Star team. Midway through the year, the Yankees promoted him to Triple-A Richmond in the International League. He finished the season hitting .258 with 11 home runs and 36 RBIs in 55 games with his new club.

In the off-season, the American League expanded from eight to ten teams, adding the Los Angeles Angels and the Washington Senators. Each of the existing organizations had to make 15 members of its 40-man roster available for a draft by the new teams and could lose up to seven of those 15. The Yankees put Thomas on their list, but neither Washington nor Los Angeles picked him.11 New York did lose several key reserves in the draft, including outfielders Bob Cerv and Ken Hunt and first baseman Dale Long. Thus, for the first time in his tenure with the organization, Thomas went into spring training with a legitimate chance to make the major league roster.12

Although he did not hit well during camp, Thomas nonetheless went north with the team. He made his major league debut in the second game of a doubleheader against the Orioles in Baltimore on April 22. It was a pinch-hitting appearance. with two down in the ninth inning and the Yankees trailing 5-3. Facing future Hall of Fame knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm, Thomas stroked a single to center field. Thomas had one more pinch-hit appearance for the Yankees the next day but grounded out leading off the fifth inning.

Roughly two weeks later, on May 8, 1961, New York traded him to the expansion Angels. The deal centered primarily on an exchange of pitchers—Ryne Duren, a reliever who had enjoyed success in New York but had fallen out of favor because of his personal problems, and Tex Clevenger, whom Yankees manager Ralph Houk had coveted since spring training.13 The Yankees also regained one of the players they had lost in the expansion draft, Cerv. The Angels got another pitcher, Johnny James. Some sportswriters considered Thomas a “throw-in.” One Los Angeles-area sports columnist dismissed him as the sort of “left-handed hitting outfielder . . . that falls out of trees without much shaking.”14

Some time after the trade, a story emerged that the Angels’ acquisition of Thomas had been furthered by the advice that two of the Yankee stars had given him. According to the Los Angeles Times, Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris recognized some talent in Thomas but saw that, given the makeup of the team, he wasn’t likely to get much playing time. Before a game the Yankees played against the Angels on their first road trip to California in early May, the sluggers suggested that Thomas arrive early and take some extra batting practice to show off his hitting ability. “They said, ‘Just go out there and try to impress them and maybe something will happen, because we heard some rumors.’” Several days later, the teams made the deal.15

Despite some lack of enthusiasm about his value, Thomas went on to have a solid rookie season. Over the next ten days with his new team, he appeared in five games as a late-inning substitute or pinch hitter. He collected his first hit in an Angel uniform, a single, in the first game of a home doubleheader against the Chicago White Sox on May 19. In the nightcap, Thomas got his first start in a major-league uniform, playing right field and batting fifth, going 1-for-3 with another single.

Two days later he became a near-fixture in the Los Angeles lineup, splitting time between the outfield and first base. He hit his first major-league home run on May 25, a solo blast against the Indians’ Jim “Mudcat” Grant, and his second round-tripper two innings later. On June 6, batting against the Orioles’ Milt Pappas at home, he hit the first grand slam in Angels history.

An August slump (only 20 hits in 95 at bats) had his average down to .265, but Thomas started hitting again once the calendar turned, beginning with a 4-for-4 day in a September 1 home game against the Kansas City Athletics. As he took the field on September 5 for the first of two against those same A’s, this time on the road, he had raised his average to .276. By the time the doubleheader ended, his 9-for-11 burst had lifted it another 16 points, to .292.

That red-letter day sparked a final month in which Thomas hit .355 with an OPS of 1.021. He finished with the second-highest average (.285) and OPS (.844) of any major-league rookie that season with at least 450 plate appearances. At season’s end, his .284 average as an Angel stood second on the team, behind Albie Pearson’s .288. He also had slugged 24 home runs with 70 RBIs. He finished tied for third in the BBWAA voting for Rookie of the Year and second in the UPI poll for top AL rookie. He also was recognized as part of the Topps All-Rookie team.

His second season was even better. Though starting slowly, only 10 for 68 (.147) through May 5, his bat awoke in a May 6 home game against Baltimore. He went 5-for-6 with four RBIs to lead the team to a 15-7 victory. Over the next 18 games, he hit .380, and by the end of May, his average was up to .278. Thomas’ performance helped the Angels, only a season removed from their creation, into contention. For a brief period, they even reached the top of the AL standings, a half-game ahead of the eventual league champion Yankees. Thomas earned a spot on both American League All-Star teams (the leagues played two Midsummer Classics from 1959-62). He got a pinch-hit groundout in the first game and played two innings in left field in the second. He recorded the final out of the latter game, catching a fly ball by future Hall of Famer Frank Robinson.

The Angels finished third that season, albeit 10 games back. Thomas ended the year leading the surprising Angels in batting (.290), hitting 26 home runs with 104 RBIs (sixth in the league) as well. He also finished 11th in the balloting for MVP.

After the season, Thomas disclosed that he had played the entire year with a bad left knee, partly the result of the high-school football injury he had suffered nearly ten years earlier. Doctors found he had loose cartilage, and during the fall, he underwent surgery and physical therapy to correct the problem.16 Nonetheless, The Sporting News anticipated that he would have an even better year in 1963.17

As it turned out, however, while Thomas occasionally approached the level of play he had in his All-Star year, he never reached those heights again. The rest of his major-league career often frustrated him and his teams. During his first two seasons, he had averaged .288 and hit 50 home runs with 174 RBIs, but over the following six years with five different teams, he averaged only .240, with 54 additional home runs and 254 RBIs.

In 1963, Thomas began the year suggesting that he would repeat and perhaps surpass his performance of the previous year. At first it appeared he might be an accurate prophet. Though he had had a miserable April the previous season, through his first ten games in 1963, he went 15-for-38, for a .357 average. Although his hitting cooled after that, he closed out the month at .284, with two home runs and 14 RBIs, good for third in the league. After that, he crashed into an almost season-long slump. Between May 1 and September 1, he hit .193, with 7 home runs and 37 RBIs. Though he rebounded slightly in September (.294 as a part-time player), he closed out the year with a .220 average and only nine home runs (none after July). A Sporting News writer characterized his season as “shocking,” adding, “No one can explain why he dropped to an anemic (average).”18

After another slow April to open 1964 (.208), Thomas hit .295 in May and started June off well. On June 3, his average was up to .273 after going 2-for-4 with a double and two RBIs to pace a 9-8 win over Boston. However, the Angels decided he no longer fit in their future plans. The next day, Los Angeles traded him to the Red Sox for outfielder Lou Clinton. With typical bluntness Thomas told reporters that the Angels had made a mistake trading him, and he would prove to them that they had.19

The Sox needed a new left-handed hitter after outfielder Gary Geiger retired following surgical complications. The day after the deal, they started Thomas in right, batting fifth. Nearly immediately, it seemed he would indeed make the Angels regret trading him. In his first seven games following the trade, he blistered the baseball with something approaching a vengeance, going 14-for-29 with two home runs and seven RBIs. He cooled off after that spree but nonetheless finished the season with more respectable numbers: .262 with 15 home runs and 66 RBIs.

Going into the 1965 season, the Red Sox made Thomas their everyday first baseman and he claimed the job emphatically. On Opening Day, he blasted a three-run home run in the third inning in a road game against Washington to give the Sox a lead they would not relinquish. Five days later, facing Jim Palmer in the future Hall of Famer’s first inning on a major-league mound, he hit a two-run single that helped Boston come back from a five-run deficit. A week after that, as part of a 4-for-6 day, he slugged a three-run, 15th-inning homer to lead the Sox to another victory over the Orioles, this time on the road. On May 1, he was batting .289 with a .622 slugging average. He finished the year hitting .271, with 22 home runs (second on the club behind league HR champ Tony Conigliaro) and 75 RBIs.

Despite his solid play, however, that season was his last with Boston. The Red Sox finished an abysmal 62-100, in ninth place, 40 games behind the league champion Minnesota Twins, and manager Billy Herman declared the team would be rebuilding with youth. One of the players he named specifically who would likely be gone in the off-season was Thomas, who would turn 30 before the 1966 season opened.20 Herman initially intended to replace him with Tony Horton because the team wanted a right-handed power hitter at first. As it turned out, they gave the job to a different right-handed slugger, George Scott, who had won the Triple Crown in the Double-A Eastern League in 1965 and would go on to an All-Star major-league career.

On December 15, 1965, Boston traded Thomas, pitcher Arnold Earley, and a player to be named later, to the Braves, who would be relocating from Milwaukee to Atlanta for the next year. In exchange, the Sox received pitchers Dan Osinski and Ray Sadowski.

Unlike his reaction to his previous trade, Thomas was “elated” over the deal that sent him to the Braves, who had finished the previous season in fifth place, but with a winning record. The team had a solid core of legitimately great players, including Henry Aaron, Joe Torre, Eddie Mathews, Rico Carty, and Felipe Alou. After the deal, Thomas told a reporter, “It’s a real break for me to get with a pennant contender. I have no hard feelings with anyone in Boston but I felt I wasn’t wanted there.”21

As for the Braves, they saw Thomas as a badly-needed asset, since they were looking for an everyday first baseman who could hit for some power, a commodity they had lacked for three seasons, ever since they’d traded away slugger Joe Adcock in 1962. Since Adcock’s departure, the team had used catchers Joe Torre and Gene Oliver and outfielder Felipe Alou at first. Without, as one sportswriter put it, “a full-time, dues-paid accredited member of the first base union,” they were likely going to be forced to install Torre there again, something neither the club nor Torre wanted.22 Although he did not hit well in camp, Thomas nonetheless impressed the team with his hard work and his willingness to do whatever he needed for the team.23 He was, wrote Furman Bisher in The Sporting News, “[o]ne reasonably bright spot, in spite of his ladylike batting average.”24

Thomas, however, did not last long with the Braves. Once again, he had a slow start to his season, and by the middle of May, his average was below .200, so Braves manager Bobby Bragan benched him.25 Finally, on May 28, the team traded him to the Chicago Cubs for relief pitcher Ted Abernathy. The Cubs were interested in Thomas despite his .198 average because they wanted a left-handed hitting first baseman who could perhaps platoon with right-handed Ernie Banks, then in the 14th season of his Hall of Fame career. Banks was having a miserable season, hitting even worse than Thomas (.183), with only two home runs and five RBIs. After Thomas announced that he was more interested in playing full-time and not merely platooning, some writers speculated that the Cubs were considering trading Banks.26

As it turned out, the trade seemed to rejuvenate Banks, who almost immediately started hitting and averaged close to .300 from the day Thomas joined the team until the end of the season. He continued hitting well through the next year, when he was an All-Star. Thomas found himself consigned to part-time duty. For the remainder of the 1966 season, he started only occasionally and appeared in only 75 games with the Cubs, roughly half as a pinch-hitter. He finished the season hitting .222 with seven home runs and 24 RBIs. The next year was much the same: he spent the entire season with Chicago, appearing in 77 games, and hitting .220 (42-for-191).

On February 9, 1968, Chicago traded Thomas to his sixth team in eight years, the Houston Astros, for two minor-league players, outfielder Levi Brown and infielder/outfielder Tommy Murray, neither of whom ever reached the majors. Thomas served primarily as a bench player with Houston. In fact, that year he set what was then a new team record for pinch-hit appearances, 43.27 But it was another disappointing season. He batted only .194 with no evidence of the power he’d once had, hitting only one home run and four doubles for a .229 slugging average. On September 27, he appeared in his last game as a major-league player. Pinch-hitting with a runner on second base, he popped out to the shortstop. (Thomas’ last big league hit had come off Cincinnati Reds pitcher Gary Nolan a week earlier. His final homer had been back on May 19, a solo shot against the Dodgers’ Mike Kekich.)

The end of his major-league playing career was even slightly more ignominious than his performance would suggest, because the Astros removed him from their major-league roster on the last day of the season. This move had a significant impact on Thomas: if he’d been on their roster for one more day, he would have completed eight full seasons as a major-league player. Under the rules then, before establishment of free agency in the 1970s, if a team assigned a player with eight major-league seasons to the minor leagues, the player had the right to negotiate with another club for a major-league job. But because he was one day shy of that, Thomas was stuck in the Astros system for at least the next year.28

Rather than play in the minor leagues, Thomas elected to go to Japan. “When Houston let me go,” he said, “I knew I would have no chance at a big league opportunity.” Don Blasingame (a fellow St. Louis resident) had played in Japan for a couple of years, “and he talked me into going over there for a year.” In 1969, Thomas was the everyday first baseman for the Nankai Hawks. He ended the season hitting a respectable .263, while finishing second on his team in home runs (12) and RBIs (50).

He returned to the U.S. the following year and, after a tryout with the Cardinals, spent 1970 with their Triple-A team in Tulsa. When the season ended, he hung up his spikes—but was far from finished with baseball. For two seasons (1971-72), he served as bullpen coach for the Cards before managing in their minor league system for two more years (1973 with the Gulf Coast League Red Birds, 1974 with Modesto of the California League).

Following that season, Thomas moved into the team’s front office, first for a year as assistant director of sales and promotions. In October 1975, he became traveling secretary, a job he held until the fall of 1980, when the team had a series of management shakeups. Former Kansas City Royals manager Whitey Herzog joined the team in midsummer that year as skipper. After the Cardinals finished a disappointing fourth, 17 games out of first, the team fired then-general manager John Claiborne, eventually giving the job to Herzog. When the team’s director of minor-league operations left, Herzog asked Thomas if he wanted the job. The two had first met in the Yankees’ minor league system in the 1950s and had renewed their friendship, going on hunting and fishing trips together. On those trips, and on the road, according to Thomas, they had talked about the Cardinals organization and its players. So when Herzog offered him the job, Thomas accepted it. Herzog later said it was one of his more brilliant moves.29

Thomas’ work for the Cardinals directly led to their success in the eight years after his appointment. At the end of Thomas’ tenure in the job in 1988, Herzog outlined for a reporter some of his friend’s accomplishments. Every number-one draft pick from 1980 to 1987, for example, reached the major leagues. It was Thomas’ idea to teach key players how to switch-hit in the minor leagues (six of the eight regulars in the team’s 1985 N.L. Championship team were switch-hitters). Thomas also suggested converting future MVP Terry Pendleton from second base to third and also recognized that talented but inconsistent pitcher Todd Worrell should be a closer. In that role, Worrell was a Rookie of the Year, a two-time All-Star, and NL Rolaids Relief Award winner.30

So when the Philadelphia Phillies fired their vice-president for player personnel in June 1988, president Bill Giles had Thomas at the top of his list of candidates to fill the open job. (At the time, the Phils’ VP of player personnel fulfilled the role of GM but without the GM title.) Twice before, Thomas had come close to a GM job (with the White Sox in 1986 and the Astros in 1987) but had lost out. This time, he got the position with an organization that had begun the decade with great promise—winning its first World Series in 1980 and then a second NL pennant in 1983—but had struggled after that. On the day Thomas moved into his new office, the Phillies were in last place in the N.L. East.31

Thomas came into the job intending to make significant changes, largely because he perceived the team as listless, lacking his notion of the sort of ideal player who could motivate his teammates—players like outfielders Lenny Dykstra (with the Mets) or Kirk Gibson (with the Dodgers).32

Over the next few years, the team continued to struggle, but Thomas set about remaking it according to his vision. As GM, he took his time before making any significant deals. He later told a writer that nearly from the first moment he took office, other general managers began calling him to make trades, but not with what he thought of as serious offers. They were, instead, attempts by more experienced GMs to take advantage of someone new. However, roughly a year to the day after he took the job, he began making a series of major deals that eventually created the Phillies’ 1993 NL championship team. In June 1989, he acquired John Kruk, Terry Mulholland—and Dykstra, in what Thomas characterized as his signature deal while with the Phillies.33 Over the next few seasons, he also dealt for Curt Schilling, Danny Jackson, and Milt Thompson, among others. Thomas acquired 20 of the 25 players on the 1993 team’s postseason roster through trades or free-agent signings. His splendid work earned him the Sporting News Executive of the Year Award for that year.

Thomas lasted another four-plus seasons with Philadelphia, which did not have another winning season the rest of the decade. The team fired him in December 1997.34 Following this, Thomas worked as a special assistant to the GM for the Boston Red Sox from 1998-2003, and as a scout for the Milwaukee Brewers until 2006. After that, he decided to retire, but he came back to the game in 2011 as a special assistant to the executive vice president of baseball operations for the Baltimore Orioles. “I decided I could only do so much hunting and fishing with Whitey (Herzog),” he said.35

When he was a player, during offseasons Thomas also worked as a car salesman and truck driver, among other jobs. He married twice. In 1955, he wed the former JoAnn Jansing; that union ended in divorce. In 1985, he married Susan Quigley, and they remained together at the time of this writing. He is the father of four children.

Last revised: March 29, 2016

Sources

Telephone interview with Lee Thomas, July 14, 2014 (hereafter “Thomas interview”)

Archives at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Beaumont High School yearbooks, 1954-55

Long Beach (CA) Press-Telegram

Los Angeles Times

New York Times

St. Louis Globe-Democrat

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Thomas interview.

2 Braven Dyer, “Strutting Seraphs Toss Leis to Lees,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1963, 15.

3 Harold Tuthill, “SLUH Beats Beaumont,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 2, 1953, 2B.

4 “Player of the Year Awards Given to Mimlitz and Ohl,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 30, 1954, 2B.

5 “Four McKinley Players on League All-Stars,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 6, 1954, 5F.

6 Thomas interview.

7 “Yankee Farms Sign 2 Local Prep Grads,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 20, 1954, 1E; “Minor League Highlights Class D,” The Sporting News, July 7, 1954, 39.

8 “Leroy’s ‘Slavery’ Support for Cut?”, Associated Press, February 8, 1970 (from Baseball Hall of Fame Archives).

9 Larry Claflin, “Thomas Erasing All Hub Doubts as Happy Hitter,” The Sporting News, May 8, 1965, 22.

10 John Drebinger, “7 Rookies Get More Attention than Regulars in Yanks’ Camp,” New York Times, February 2, 1960, 34.

11 Louis Effrat, “It’s Either too Young or too Old,’” New York Times, November 19, 1960, 15.

12 John Drebinger, “Yankees to Seek 7 New ‘Regulars,” New York Times, January 25, 1961, 38.

13 John Drebinger, “Yankees Trade Duren and Three Others to Angels for Cerv and Clevenger,” The New York Times, May 9, 1961, 47.

14 Hank Hollingsworth, “Angel Trade Roasted.” Long Beach Press-Telegram, May 18, 1961, 36.

15 Andrew Owens, “Angels Having Another ‘T’ Party,” Los Angeles Times, June 7, 2012, accessed February 29, 2016, http: //articles.latimes.com/2012/jun/07/sports/la-sp-0608-angels-trumbo-trout-20120608.

16 Braven Dyer, “Doctors Order Knee Operation for Lee Thomas,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1962, 13.

17 “Scribes Slants on A.L. Players,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1963, 14.

18 Braven Dyer, “Angels Close Books with Dreary Debit—29 One-Run Losses,” The Sporting News, October 12, 14.

19 Larry Claflin, “‘Angels Made a Bad Mistake,’ Says Thomas; Hub Fans Agree,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1964, 12.

20 Larry Claflin, “Kids to Hold Key to Bosox Infield Blueprint for ’66,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1965, 25.

21 Larry Claflin “Thomas Elated Over Deal That Sent Him to Braves,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1966, 12.

22 Furman Bisher, “Thomas Will Free Torre for Duties as Backstop,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1966, 10.

23 Furman Bisher, “Braves Suffer Dizzy Feeling as Hurlers Ride Teeter-Totter,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1966, 15.

24 Furman Bisher, “Judge Roller Courtroom Swing Blamed for Braves’ Swat Plunge,” The Sporting News, April 30, 1966, 16.

25 Wayne Minshew. “Peace Reigns Again in Tepee Following a Torrid Family Tiff,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1966, 10.

26 Richard Dozer, “Cubs Trade Abernathy for Braves’ Lee Thomas,” Chicago Tribune, May 29, 1966, B1.

27 John Wilson. “Here Comes the Groom—But He’ll Be on Crutches,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1968, 44.

28 “Leroy’s ‘Slavery’ Support for Cut?”; Thomas interview.

29 Thomas interview; Jayson Stark. “So Who Is Lee Thomas and Where Did He Come From?”, Philadelphia Inquirer, June 19, 1988, accessed February 29, 2016, http://articles.philly.com/1988-06-19/sports/26265695_1_herzog-cardinals-position-people.

30 Stark, “So Who is Lee Thomas and Where Did He Come From?”

31 Bill Brown, “Thomas Has Authority If Not Title,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1988:13; Stark, “So Who is Lee Thomas and Where Did He Come From?”

32 Peter Pascarelli, “Irked But Patient, Lee Thomas Looks Ahead,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 2, 1988, accessed February 29, 2016, http://articles.philly.com/1988-08-02/sports/26255259_1_lee-elia-phillies-effort.

33 Frank Fitzpatrick, “Lee Thomas: A Guy Who’s All Business When It Comes To Deals The Phillies’ GM Is Interested Only In Trade Talk, Not In Small Talk. It’s A Philosophy That Has Served Him Well,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 18, 1993, accessed February 29, 2016, http://articles.philly.com/1993-07-18/sports/25976977_1_trade-policy-thomas-trades-patience.

34 Jim Salisbury, “Lee Thomas Is Fired by the Phillies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 10, 1997, accessed February 29, 2016, http://articles.philly.com/1997-12-10/news/25556098_1_major-leagues-lee-elia-ed-wade.

35 Thomas interview.

Full Name

James Leroy Thomas

Born

February 5, 1936 at Peoria, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.