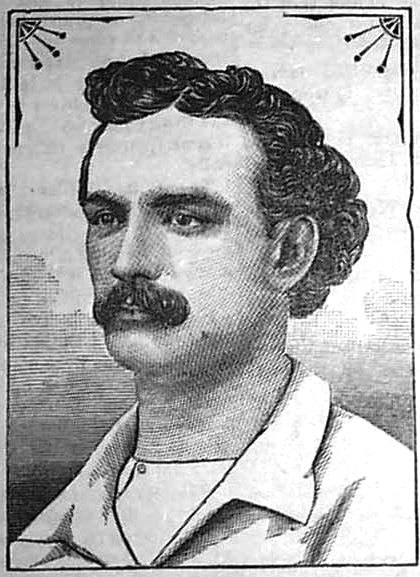

Lip Pike

Born May 25, 1845, Lipman Emanuel Pike was the first great Jewish baseball player, playing professionally from 1866 to 1881. While no comparable statistical records exist for his career through 1870, from 1871 through 1881 Pike appeared in 425 National Association and National League games, hitting .322 with a slugging average of .468. Despite being “small by modern standards (5-foot-8, 158 pounds),”1 Pike nonetheless was among the premier sluggers of his time.

Born May 25, 1845, Lipman Emanuel Pike was the first great Jewish baseball player, playing professionally from 1866 to 1881. While no comparable statistical records exist for his career through 1870, from 1871 through 1881 Pike appeared in 425 National Association and National League games, hitting .322 with a slugging average of .468. Despite being “small by modern standards (5-foot-8, 158 pounds),”1 Pike nonetheless was among the premier sluggers of his time.

The son of a haberdasher,2 Pike, according to the Big Book of Jewish Baseball, “…[w]as born in New York City. He was the son of Emanuel and Jane Pike. The Pike family were Jews of Dutch origin. Lip had an older brother, Boaz, two younger brothers, Israel and Jacob, and a sister, Julia. The Pike family moved to Brooklyn when Lipman was very young. “Boaz was the first of the Pike brothers to play base ball. Just one week after his bar mitzvah, Lip appeared in his first recorded game, along with Boaz. This was an amateur game.”3

Playing for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1866, for whom the “long ball was a prominent part of [their] arsenal”, Pike “had numerous multi-homer games” on a team that boasted several sluggers “capable of smashing the ball beyond the reach of opposing fielders.”4 The events of July 16, 1866, give an indication both of Pike’s home run prowess and of the nature of the game at the time. Pike hit five home runs in succession against the Alert club of Philadelphia. The final score was 67-25.5

Also in 1866, Pike played a major role in the professionalizing of the game as “Philadelphia City Item publisher Fitzgerald…charged the club with paying two or possibly three members of the first nine (reportedly Dockney, McBride and Pike) $20 per week.”6 Meanwhile, The Biographical History of Baseball reported:

“Pike was one of the first players to be acknowledged as a professional. While others had certainly been paid before 1866, Pike, along with two teammates on the ostensibly amateur Philadelphia Athletics, was ordered to appear before the judiciary committee of the governing National Association of Base Ball Players to answer charges that he had accepted $20 for his services. Although the matter was dropped when nobody bothered to show up for the hearing, the incident exposed for the first time the wide spread practice of paying supposedly amateur players.”7

This was perhaps the first step in legitimizing the practice of play for pay. By 1869 acceptance of this idea allowed all-professional teams to be admitted to the Association. However, the professional teams proved to be so far superior to the amateur teams that matches between them were laughable. This led to the formation of the first all-professional league in 1871. This, in turn, sounded the death knell for organized amateur baseball and its governing body, The National Association of Base Ball Players.

Overall, Pike seems to have had a fine season with the outstanding Philadelphia Athletic club of 1866, appearing in 16 of 25 games for a team that went 23-2. Playing the outfield as well as second and third base, Pike, in the rudimentary statistics of the day, made an average of 2.7 outs per game while scoring 6.4 runs per game.8

At the conclusion of the 1866 season, dissatisfaction with non-native professional players became a major issue with the Philadelphia club, leading to Pike’s dismissal from the team:

“The two salaried players who had been imported from New York (Dockney and Pike) were jettisoned in favor of Philadelphians. This experiment had never worked the way management had hoped. Whenever the play of the Athletics had been considered suspicious, the two ‘foreigners’ had been the most suspected. It seemed that, as nonnatives [sic], their loyalty was perpetually in question. With the exception of Reach, all of the 1867 regulars were local boys.9

In 1867, Pike played for the well-respected and powerful Irvingtons of New Jersey, (in six of the Irvingtons’ 23 games, all at third base) and for the first rate Mutuals of New York (in 21 of the Mutuals’ 30 games, in the outfield, first, second, and third base). He appeared exclusively for the New York Mutuals in 1868, hitting a robust .497, with a .661 slugging average for a Mutuals team that went 31-10.10

Pike returned to his native Brooklyn in 1869 where he played for one of the nation’s leading teams, the Brooklyn Atlantics. For the first time the National Association of Base Ball Players recognized the professional class of player and team. Overall, against all comers, the Atlantics racked up 40 wins against six losses, with two ties. However, the Atlantics record against teams composed exclusively of professionals fell off to 15 wins, six losses, and one tie. This was Pike’s first season as a full-time player, as he appeared in all 48 games, hitting .610 with an astonishing slugging average of .883. Without diminishing Pike’s performance, the modern reader is reminded that in 1869 the batter called for his pitch, telling the pitcher his preference for either a high or low ball, and foul balls did not count as strikes. In addition, the pitcher tossed the ball up to the batter in an underhand motion without snapping his wrist. In other words, the batter did not have to contend with either blazing fastballs or any sort of curve balls. The game was very similar to today’s slow pitch softball.

Pike stayed with the Atlantics through the 1870 season, in which the team went 41-17, with 20 wins and 16 losses against professional teams. Pike again played second base in all of the Atlantic games, averaging 2.48 hits and 4.58 total bases per game.11

When the first system of government for professional baseball teams was organized for the 1871 season, The National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, Pike joined the entry from Troy, New York, with the New York Clipper announcing that he “has been elected captain of the Haymakers of Troy…”12 In the nineteenth century the captain was in fact the field manager. He determined who played what position, the batting order, as well as directing play on the diamond, while the manager filled what today would be called the role of the general or business manager.

The season got off to an auspicious start for Pike and his nine, as “[t]he heavily favored Mutuals [we]re soundly defeated by the Haymakers of Troy, in Brooklyn, 25-10. Lipman Pike, the Troy second baseman, collect[ed] six hits.”13

Pike’s first year in the newly formed professional league was a smashing success. Playing outfield, first base and second base for a Troy team that finished sixth in a nine-team league, Pike tied for the league lead in home runs (4), placed second in slugging average (.654), third in total bases, fourth in RBIs, and sixth in batting average (.377). However, Pike did not fare too well as captain, turning the helm over to second baseman Bill Carver after three losses in four games.

Lip Pike joined the Baltimore team for the 1872 season. Officially, the team name was “The Lord Baltimores” but because of their bright yellow shirts with matching caps and hose, they were popularly known as “The Canaries.” The team owners had vigorously recruited outstanding players during the off-season, and their efforts were rewarded with a second-place finish (in an 11-team league.) Overall, Pike, playing 56 of his team’s 58 games, led the league in home runs (with seven) and RBIs, finishing second in total bases, while hitting a respectable .298.

Continuing with Baltimore in 1873, Pike hit a fine .316 while again leading the league in home runs with four. As reported in The Baseball Chronology, Pike also found time for an exhibition of his speed in August of that year: “At Baltimore’s Newington Park, Baltimore outfielder Lipman Pike races against a horse named ‘Clarence.’ Pike has a short lead after 75 yards when the trotter breaks into a run. Pike holds on to win in 10 seconds flat.”14

Prior to the 1874 season, “Power hitting Lip Pike, released from his contract with the bankrupt Baltimore organization, signed on as Captain and center fielder” for the Hartford Blue Stockings.15 As the Blue Stockings’ “one bona fide star,”16 Pike enjoyed another excellent season, finishing third in hitting at .355, second in on-base percentage, and first in slugging (.504).

For the 1875 season, Pike signed on with the St. Louis club, leaving a bad taste in the mouths of many in Hartford: “Pike, never reticent, offended many in Hartford with his constant boasting of the havoc his new team would wreak on the old.”17

In 1876, the National League replaced the National Association as the premier organization for professional teams. Indeed, virtually all the old Association teams, at the urging of the League’s principal motive force, William Hulbert, simply registered with the new League, leaving the Association an empty shell. It vanished into history without a trace. Pike remained with the new St. Louis NL squad that finished a very respectable second behind the overpowering Chicago White Stockings. Pike batted a solid .323, finished third in slugging (.472), and fifth in total bases. Batting cleanup, then later moving to the leadoff spot, he led his team in every major offensive category, except runs scored and walks.

Prior to the 1877 season, Pike changed teams yet again, this time signing on as captain with the lackluster Cincinnati Reds. “The new fair-foul rule (for 1877) did not hurt the hitting style of … Pike, a four-time home run champion in the 1870s,”18 but despite leading his league in home runs again, hitting .298, and “excel[ling] defensively as a swift center fielder … his heroics were not enough to keep Cincinnati from finishing last in the league for the second consecutive year.”19 All that losing seems to have cost Pike the captain’s helm, as “Pike resign[ed] as Cincinnati Captain (following a 13-2 loss to St. Louis)” on June 10, and was “succeeded by Bob Addy. Pike continue[d] as the starting center fielder.”20

It appears that being a left-handed middle infielder finally caught up with Pike in 1877, as David Nemec reports:

“Pike played the most games on the [Cincinnati] team at both second base and center field. He moved permanently to center field following a game played in Brooklyn on Aug. 18, 1877. The New York Clipper observed, ‘Pike is a splendid outfielder and quick in handling the ball on the bases, but his left-handed throwing unfits him from second-base playing.’”21

Despite league-leading home run totals that are miniscule compared to the modern era, Pike’s status as a true power hitter should not be dismissed. As stated in Before They Were Cardinals, while “Pike’s totals …were ludicrous by today’s standards — he won his four (home run) titles by hitting a combined total of eighteen home runs. … As the home run became more commonplace, the game’s leading sluggers actually hit a smaller percentage of the overall home runs. In Pike’s best season, 1872, his league-leading six home runs accounted for 17.1 percent of the thirty-five home runs hit in the National Association that year. Thus, the 1872 season marked one of only twenty-one occasions in baseball history when a league’s leading home run hitter accounted for more than 10 percent of all the league’s home runs.”22 In addition, he finished in the top ten in slugging and in doubles in seven consecutive seasons, in total bases and triples six times, and OPS five times. All this was accomplished in a career spanning just eight relatively full professional seasons.

Perhaps his most famous feat of power probably occurred in this season of 1877, as the Sporting Life of May 27, 1883, reflecting on the demolition of Brooklyn’s Union Grounds, spoke of “the pagoda from which rises the rod once bent by a ball struck from the home plate by ‘Lip’ Pike.”23 How far from home plate was the rod atop the pagoda? The precise dimensions of the Union Grounds were lost forever when it was razed on May 28, 1883. However, the late Larry Zuckerman (a SABR member whose specialty was reconstructing the dimensions of the ball grounds of yesteryear) provided the following information:

“Union Grounds was between Harrison and Marcy Avenues (sort of east and west) and Rutledge and Lynch Streets (sort of north and south). The field featured a horseshoe shaped grandstand, facing west from Harrison. There was a board fence about 10 feet high surrounding the park, parallel to the streets and about 10 feet inboard of the sidewalks. Assuming a midline location of home plate, the foul lines would have been about 310 feet with dead center about 470 feet. … The pagoda seems to be in right center, more or less on a line drawn from home plate to the Marcy-Rutledge corner. I would put it at about 360 feet from home plate, perhaps more distant …”24

Imagine a batted ball crashing into a metal rod about forty feet above the ground level, and 360 feet away from home plate, with sufficient force to bend the rod!

Zuckerman continues:

“In 1877 Pike hit the ball over the ladies stand — I have no idea what that means or where it was — but the ball was still in play and he beat it out for an inside the park home run. The paper said it was the longest home run at the park since the introduction of the dead ball, suggesting that it was not as long as some of the 1876 shots …”25

Pike re-signed with the Cincinnati nine for the 1878 season. The infamous reserve rule was not enacted until 1879, and the players were free agents once their contract expired at season’s end. An account in the May 21, 1878 Redleg Journal gives further evidence of Pike’s enormous power:

“Lip Pike’s long drive highlights a 13-2 win at Lakefront Park in Chicago. Pike’s blast not only cleared the fence, but a freight shed and a half dozen railroad cars. Pike only earned a double on this hit, however, because of the ground rules of the ball park. Built on a narrow lot between Michigan Avenue and the railroad yards, Lakefront Park had foul line of less than 200 feet. Balls hit over the fence were considered doubles. Pike’s hit was of such force, however, that the Enquirer felt obliged to estimate the distance: 200 yards! No doubt Pike’s drive was a mighty wallop, but 600 feet strains credulity.”26

The left field line at Lake Front Park was 180 feet, while the right field line measured 196 feet. Straight away center field was about 300 feet. There were two poles located along the outfield fence, one in left-center and the other in right-center. The ground rule provided that any fly ball clearing the fence between these two poles was an “automatic” home run. Any other over-the-fence fly balls were merely doubles. Pike must have pulled his ball rather sharply down the right field line.

Cincinnati’s acquisition of “Buttercup” Dickerson spelled the end of Pike’s tenure there, as related by David Nemec:

“After playing 31 games and hitting .324 in the lead-off position, Lip Pike was released by the Cincinnati team. This is due to Louis ‘Buttercup’ Dickerson joining the team, even though Pike went 2-for-6 in his last game vs. the Providence Grays on July 9. Dickerson batted .309 in 29 games for the Reds. Lip was signed by the Providence team and debuted with them on July 31. He played second base and batted third. On August 8, he went 0-for-7, made three errors and was released the next day. Pike was replaced by Charlie Sweasy at second base. Sweasy hit only .175 in 55 games and committed 54 errors so it is difficult to understand how he improved the team.”27

But Pike got some measure of revenge, as The Baseball Chronology reports the events of July 31, 1878: “Lip Pike, released by Cincinnati, goes 4 for 5 with 3 RBIs for Providence, as the Greys beat his old team 9-3.”28

Pike slipped down to the minor leagues in 1879 and played for teams in Springfield and Albany. Captain and center fielder for the Springfield club, he appeared in a total of 53 games and hit .356.

Beginning the 1880 season with Albany, Pike showed he still had home run power, as evidenced by this report in The Baseball Chronology regarding the game of May 21, 1880: “In Albany’s Riverside Park, Lip Pike hits a ball over the wall and into the river. Right fielder Lon Knight begins to go after the ball in a boat but gives up. Few parks have ground rules about giving the batter an automatic home run on a hit over the fence.”29

According to David Nemec:

“Pike played for the Albany team until it disbanded in July. He then played for the Unions of Brooklyn in a three-team tournament held at the Union Grounds on August 18, featuring the Washington and Rochester teams. Pike also played for the New York Metropolitan team. He appeared in a total of 12 games and batted .241.30

“Pike opened the [1881] season playing second base for his old Atlantic team in a minor league and working in the mercantile business. However, in late August he was called up by the National League Worchester Ruby Legs when Arthur Irwin was disabled. He joined Worchester on August 27, played center field and batted second. In six games he went 3-for-25, a mere .120 batting average.”31

Pike’s miserable play for the Worchester club led to controversy, as noted in The Baseball Chronology’s account of events as the season of 1881 drew to a close:

- September 3: “Center fielder Lip Pike makes 3 errors in the 9th inning to give Boston 2 runs and a 3-2 victory over Worchester. The losing club immediately accuses Pike of throwing the game and suspends him.”32

- September 29: “At a National League meeting in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., the league adopts a blacklist of players who are barred from playing for or against any NL team until they are removed by the unanimous vote of the league clubs. These men are: Sadie Houck, Lip Pike, Lou Dickerson, Mike Dorgan, Bill Crowley, John Fox, Lew Brown, Emil Gross, and Ed Caskin.”33

His baseball career essentially over, Pike “became a haberdasher in Brooklyn. … Lip’s haberdashery became a successful business and a meeting place for local base ball enthusiasts. After the expiration of his year’s ban, Lip decided to continue with his business enterprise.”34

While his professional career was over, Pike continued an interest in the game, “playing center field for an amateur club on Long Island.”35

Finally, as reported by David Nemec, Pike made one final attempt to play at the major league level. It came on July 28, 1887:

“At the age of 42 Pike played center field and batted sixth for the New York Metropolitans, an American Association team. He was supposed to pitch, but switched to the outfield at the last moment. The papers reported that his fielding was good, but ‘at the bat he was quite weak.’”36

Pike “died of heart disease on October 10, 1893 in Brooklyn, at the age of 48. His funeral was a notable event, attended by much of the Jewish and baseball communities of Brooklyn. The services were conducted by Rabbi Geismer of Temple Israel and, according to the Brooklyn Eagle, he ‘paid fitting tribute to the exemplary life led by the deceased.’”37

In subsequent issues, The Sporting News published a series of tributes to Pike, indicating his stature as one of the greats of his time:

“Pike was the center fielder of the Atlantics of Brooklyn in the latter’s palmiest days and as an all-round batsman, fielder and base runner he had few if any superiors. He was a left-handed batsman and in his day could hit the ball as hard as any man in the business. He was a right field hitter and during his career had sent balls over the right field fence of nearly every park in which he had played in.”38

“Pike … was one of the few sons of Israel who ever drifted to the business of ball playing. He was a handsome fellow when he was here, and the way he used to hit that ball was responsible for many a scene of enthusiasm at the old avenue grounds…The roster of ball players who once wore the red and who have been called out by Umpire Death is not very large, but in the passing away of ‘Lip’ Pike one of the greatest sluggers who ever batted for Cincinnati has joined the file in eternity.”39

“The death of ‘Lip’ Pike removes another of the veterans of the seventies from the ranks of the men who played as stars when most of the present favorites were babies. I remember Pike’s ball playing best through a hit which I saw him make at Cincinnati. … He hit the first ball pitched and none who saw that ball sail out over the right fielder’s head will ever forget it. It went not only over the right field fence, but continued to sail until it cleared the brick kiln beyond and dropped into the high weeds bordering on Mill Creek. I am impressed with the belief that if the distance could be measured that hit of Pike’s would go on record as the longest fly ball ever made. The last time I saw Pike — which was during the New Yorks’ last series of Championship games at Eastern Park — we rode together in the elevated train from the ball ground, and he recalled that famous home run with a great deal of pride. Some one of the players on that day had made a home run, and ‘Lip’ could not refrain from comparing it with the greatest incident in his professional career.

“… Those who knew Pike appreciated him most. He was one of the few ball players of those days who were always gentlemanly on and off the field, a specie which is becoming rarer as the game grows older. Such men as Pike, Barnes, Spalding, Reach, Jim White, George Wright, and Morill, creditable to the game professionally and personally, are becoming scarcer every year.”40

Several honors came to Lipman Pike in the years following his death. The publisher of Philadelphia’s prestigious Sporting Life, Francis Richter, constructed hypothetical all-star teams in 1911. Richter selected Pike as one of his three outfielders for the 1870-1880 time period.

The Base Ball Writers of America held the inaugural election for the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 1936. Despite the fact that Pike had been dead for more than 43 years and his playing career had ended years before most, if not all, of the electors were born, he still received one vote. So, to some small extent, his achievement as baseball’s first notable slugger was recognized.

Finally, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball reports that Lipman Pike was elected to the Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in Netanya, Israel, in 1985.41

Last revised: June 3, 2021 (zp)

1 William Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings: A History of Baseball’s National Association, 1871-1875 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1992), 33.

2 Melvin L. Adelman, A Sporting Time: New York City and the Rise of Modern Athletics, 1820-70 (Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 178.

3 Peter S. Horvitz and Joachim Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball (New York: SPI Books, 2001), 134.

4 William Ryczek, When Johnny Came Sliding Home: The Post-Civil War Baseball Boom, 1865-1870 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1998), 87-88.

5 James Charlton, ed. The Baseball Chronology: The Complete History of the Most Important Events in the Game of Baseball (New York: Macmillan, 1991), 16.

6 Ryczek, When Johnny Came Sliding Home, 87-88.

7 Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, The Biographical History of Baseball (New York: Triumph Books, 1995), 362.

8 Data taken from Marshall D. Wright, The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857-1870 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2000), 114-115.

9 Ryczek, When Johnny Came Sliding Home, 11.

10 Wright, 145-146 and 150-151.

11 Wright, 298.

12 New York Clipper, April 22, 1871.

13 Charlton, 19.

14 Charlton, 23.

15 Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings, 133.

16 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball (New York: Dutton Books, 1997), 54.

17 Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings, 179.

18 Jon David Cash, Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2002), 3.

19 Cash, 38-39.

20 Charlton, 32.

21 Private e-mail from David Nemec, August 7, 2002.

22 Cash, 3.

23 Sporting Life, May 27, 1883.

24 Private e-mail from Larry Zuckerman, March 25, 2000.

25 Zuckerman email, March 25, 2000. Larry Zuckerman passed away shortly after this exchange of e-mails without completing his landmark ballpark project.

26 Greg Rhodes and John Snyder: Redleg Journal: Year by Year and Day by Day With the Cincinnati Reds Since 1866 (Road West Publishing, 2000), 54.

27 Nemec e-mail, August 7, 2002.

28 Charlton, 36.

29 Charlton, 41.

30 Nemec e-mail, August 7, 2002.

31 Nemec e-mail, August 7, 2002.

32 Charlton, 45.

33 Charlton, 46.

34 Horvitz and Horvitz, 135.

35 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 25, 1994.

36 Nemec e-mail, August 7, 2002.

37 Horvitz and Horvitz, 135.

38 The Sporting News, October 14, 1893.

39 The Sporting News, October 21, 1893.

40 The Sporting News, October 21, 1893.

41 Horvitz and Horvitz, 135.

Full Name

Lipman Emanuel Pike

Born

May 25, 1845 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

October 10, 1893 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.