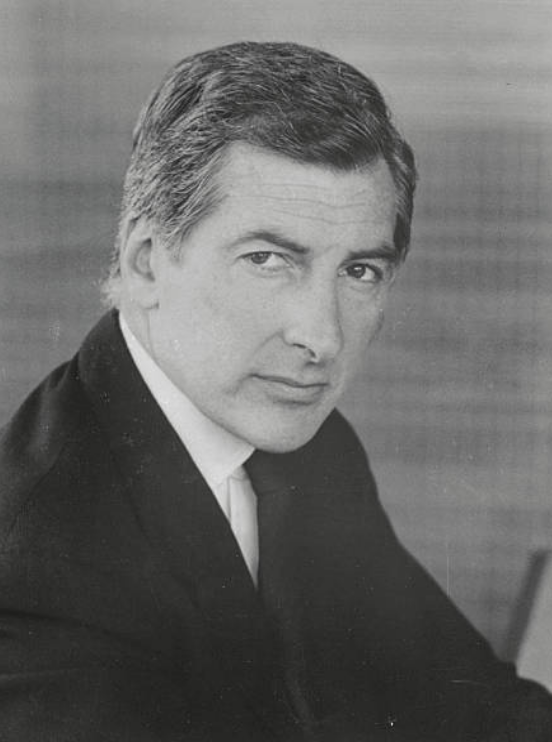

Michael Burke

Words cannot contain Mike Burke. A man of boundless courage and matchless charm, by the time he became president of the New York Yankees in 1966, he had already fought the Nazis with the French Resistance, tried to overthrow communist governments for the CIA, served as the model for a movie spy, and run the Ringling Brothers circus.

Words cannot contain Mike Burke. A man of boundless courage and matchless charm, by the time he became president of the New York Yankees in 1966, he had already fought the Nazis with the French Resistance, tried to overthrow communist governments for the CIA, served as the model for a movie spy, and run the Ringling Brothers circus.

Burke deserves a share of the credit for saving Yankee Stadium and keeping the city’s marquee team from moving to New Jersey. Although several of his ventures were failures, and the Yankees didn’t claim a pennant during his six-plus years at the helm, he wore a Teflon jacket. He never got the blame, or acknowledged any.

His was a life of name-dropping. Boldface names. Drinking with Hemingway in Paris and Cuba. A houseguest of Eleanor Roosevelt. An all-nighter with Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford. Ingrid Bergman. Gary Cooper. Soviet spy Kim Philby. TV titans William Paley, Walter Cronkite, and Howard Cosell. “He knew everybody,” sportswriter Mike Lupica wrote. “He did everything.”1

One boldface name defeated him: George Steinbrenner.

Edmund Michael Burke was born in Enfield, Connecticut, on June 8, 1916.2 Both of his grandfathers had emigrated from Ireland, and they became friends; Michael Fleming drank at Patrick Burke’s tavern. Mike was the first of three children of Mary (Fleming) and Patrick Burke Jr., a Yale Law School graduate who worked for an insurance company in Hartford, Connecticut.

Growing up in a middle-class family, Mike remembered seeing Babe Ruth hit a home run at Yankee Stadium. He won a football scholarship to the posh private Kingswood School, where he learned the ways of the moneyed class, and rode football to another scholarship at the University of Pennsylvania. He earned a starting job as a 6-foot-1, 180-pound halfback, playing both offense and defense and returning kicks. By the time he graduated, he had married a New York model, Faith Long.

Burke signed with the NFL Philadelphia Eagles, but quit when he decided it wasn’t worth risking his neck for $125 a game and began selling marine insurance. A chance meeting with World War I hero “Wild Bill” Donovan at a party shortly after Pearl Harbor was his ticket to fame and wealth. Donovan recognized Burke from football and recruited him for his new intelligence agency, the Office of Strategic Services.

Working behind enemy lines for the OSS, Burke was a genuine war hero. He helped to spirit an Italian admiral — an expert in torpedo technology — out from under the noses of the Nazis, a mission that won him a Silver Star and a Navy Cross. Parachuting into occupied France, he fought alongside the Resistance until the nation was liberated.

The hero came home to a dead marriage. Having acquired a new man, Faith left with their daughter, Patricia. Adrift, Burke jumped at an offer to go to Hollywood as technical adviser on a movie about the OSS. The babe in filmland found the producers and writers struggling to devise a suitably dramatic plot. After he described his mission in Italy, it became the basis for Cloak and Dagger with box-office superstar Gary Cooper doing the derring.

Burke married a studio publicist, Timothy “Timmy” Campbell, and they had a daughter, Doreen. As he entered his 30s, he was floundering, failing to make it as a screenwriter and collecting rejection slips as a freelance writer. He borrowed $5,000 from his father to feed his family. “I had two skills: football and guerrilla warfare,” he wrote later.3

One of those skills was marketable. Burke joined the new Central Intelligence Agency in 1948. His first assignment was to promote an uprising against the communist government of Albania. Based in Rome, he armed Albanian exiles and infiltrated them into the country. None of the irregulars was ever heard from again. Kim Philby, the British liaison with the CIA who was feeding secrets to the Soviet Union, had betrayed the operation.4

The CIA next sent Burke to Berlin under cover as an adviser to the U.S. High Commissioner in Germany. His real job was organizing resistance groups in the Soviet satellite countries behind the Iron Curtain. That effort was about as successful as his Albanian adventure. He fretted over the morality of sending people into hostile territory on futile missions: “Even if underground movements had succeeded in gaining enough strength in numbers and arms to rise up, what armies of the West would intervene to ensure their success? None.”5

The OSS old-boy network presented him with a way out and a chance to make money. Henry Ringling North had been one of Burke’s partners on the Italian mission. Burke became friends with Henry and his older brother, John, CEO of the Greatest Show on Earth, and came aboard as general manager despite his protest that he knew nothing about the circus.

He quickly learned that John Ringling North didn’t know much and had told him less. Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey was in debt up to its elephants’ ears. Managers of the traveling show, known as the Sneeze Mob, were stealing from the till at will.

Burke fired the Sneezes, punched out a gambler who was fleecing the employees, and secured television deals that generated enough cash to pay the day-to-day bills. He soon had a bigger problem in the person of James Hoffa, the thuggish president of the Teamsters union. After Burke rejected Hoffa’s demand for a union contract, the Teamsters began a campaign of picketing and sabotage. Burke blamed Hoffa for forcing him to cut the 1956 tour short and strike the Big Top forever. When the circus re-opened, it played in sports arenas.

Burke’s experience negotiating with the television networks had kindled his interest in that industry, and his experience in Europe appealed to top executives at CBS. He went to London to plant CBS’s flag in Europe, spending five years as an international dealmaker.

The work didn’t satisfy his lust for adventure. After the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961, Burke’s former boss, CIA director Allen Dulles, paid for the disaster with his job. In what Burke called his patriotic duty — others would say hubris — he wrote a letter to President Kennedy, whom he had never met, proposing himself as Dulles’s successor. “I could run the CIA as well as anyone I know,” he told the president. A White House assistant responded with a polite brush-off.6

Burke moved easily among Europe’s business and society elite, and his star was rising at CBS. Chairman William S. Paley, eager to expand beyond broadcasting, brought him to New York as vice president for diversification. His assignment was to make deals, but not just any deal; CBS styled itself the Tiffany network, and Paley wanted to buy only platinum businesses. “Paley called me three to six times a day,” Burke remembered.7 Brainstorms to take over IBM and Time Inc. came to nothing. The company acquired Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, a major book publisher, and Fender, a maker of high-end guitars.

Burke was often credited with recommending one of CBS’s most profitable investments, in the musical My Fair Lady, but he made no such claim. He did propose bankrolling another hit, Fiddler on the Roof. Paley, unwilling to highlight his own heritage, signaled his disapproval with a question: “Do you think it’s too Jewish?”8

Paley’s biographer, Sally Bedell Smith, wrote that the network’s purchase of the New York Yankees began with a golf-course chat between the chairman and Yankees co-owner Dan Topping.9 The Yankees, on the way to their fifteenth American League pennant in 18 years, were sufficiently gilt-edged to suit Paley, although the deal made barely a blip on CBS’s balance sheet.

The network paid $11.2 million for 80 percent of the team. (It later bought the other 20 percent from Topping and his partner, Del Webb, for an additional $2 million.) News of the sale in August 1964 hit the baseball world with the force of a beanball. Not only was a huge corporation gobbling up the game’s most lustrous franchise, but that corporation was a television network. Sportswriters had been ranting for years about how TV was taking over baseball, and here was the proof. “This is the blackest day in baseball since the Black Sox scandal,” Houston co-owner Roy Hofheinz fumed.10 The furor delayed final approval of the deal until November.

Burke became CBS’s point man in watching over the investment. Trying to mute the controversy, he insisted the network would be a hands-off owner: “We’re not trying to kibitz the Yankees from 52nd Street.”11 Topping remained as team president while Burke kept his office at CBS, although he attended most home games.

CBS’s crown jewel turned out to be glass, all too fragile. The Yankees won the 1964 pennant, but fired manager Yogi Berra after losing the World Series to St. Louis — and hired the Cardinals’ manager, Johnny Keane — in 1965 the unthinkable happened: The club posted its first losing record in 40 seasons as it fell to sixth place in the 10-team American League.

“The trouble was, we didn’t go in and feel the goods,” Burke explained later, shifting the blame to his boss. “Paley trusted Topping, but Dan had let the franchise go to pot. We bought a pig in a poke.”12 Mickey Mantle’s knees were shot, and the rest of the team was hardly worth shooting. The 1966 Yankees sank to the bottom of the standings for the first time since 1912.

As the season limped to a painful end, CBS forced Topping out and completed its takeover. Burke was installed as president. On his first day, September 22, the smallest “crowd” in Yankee Stadium’s history, 413 people, watched the club lose to the White Sox.

Burke’s urgent task was to restore the lost luster. He retained the respected manager, Ralph Houk, and hired Lee MacPhail as general manager. MacPhail had been the Yankees’ farm director before he moved on to become president and GM in Baltimore. The Sporting News had just named him Major League Executive of the Year for building the Orioles into a World Series champion in 1966. He leveled with the fans and the media: It could take five years to turn the Yankees into a pennant contender.

While leaving baseball decisions to MacPhail, Burke set out to overhaul the Yankees’ arrogant image. Attendance had trailed the last-place but lovable Mets every year of CBS’s ownership. “[W]hether justified or unjustified, the Yankees had a terrible image at that time,” said Howard Berk, who came with Burke from CBS, “cold, uncaring, not involved in city life, more interested in General Motors executives coming to the games than the fans.”13 Burke spent more than $1 million to paint and spruce up the 44-year-old stadium. He held an open house for 1,300 season ticket holders, a first for the Yankees, and led them on a tour of the clubhouse. Tens of thousands of children received free tickets. The notoriously surly ushers and security personnel got lessons in politeness.

Burke turned his charm on New York’s suspicious sportswriters. He gave them his home phone number and regaled them with stories of his wartime exploits. (His CIA service, still classified, was never mentioned.) At his first press conference, he perched casually on a table in his office with his feet dangling instead of sitting behind his desk. “Part of my job, as I saw it, was to personalize, to warm up the Yankees, especially in their deplorable position,” he said afterward.14 He tried to make himself, rather than the faceless corporation, the face of the franchise.

“Mike was dashing,” wrote Marty Appel, an apprentice publicist for the team. Burke’s shaggy gray hair spilling over his collar, stylish Italian pinstriped suits, and wide ties stamped him as a man of the ’60s instead of one entering his 50s. As a mark of noblesse oblige, he affected shirts with frayed collars and cuffs. His second marriage had broken up (he and Timmy had three children), and “his girlfriends were the tall and thin model types.” He guarded his public image; Appel remembered Burke editing his biography in the media guide, adding “for heroism” after the mention of his Silver Star.15

In his first full season in charge, the Yankees inched up to ninth place, although they lost 90 games, one more than when they finished last. Attendance improved by 12 percent, but still lagged 300,000 behind the Mets. Burke roamed around the vast grandstand on game days, chatting with the customers while letting the staff know that the boss was watching.

Bill Paley became a frequent visitor to the owner’s box, bringing his elegant wife, Babe, and their society friends. “He was like a ten-year-old child,” Burke remarked.16 Paley claimed he had wanted to own a baseball team ever since he shagged fly balls during batting practice at Wrigley Field as a boy.

On Opening Day in 1968, Burke invited the 81-year-old poet Marianne Moore to throw out the ceremonial first ball. Rookie catcher Frank Fernandez caught Moore’s toss, kissed her on the cheek, then hit the game-winning homer in a 1-0 victory over the Angels. The Yankees climbed to an 83-79 record, back on the winning side of the ledger and good for fifth place, but the onetime Bronx Bombers batted only .214, worst in the majors, and attendance fell. The pinstripe mystique had given way to impatience among the fan base.

The hobbled Mickey Mantle batted .237 in his final season, dragging his lifetime average below .300, though he was still a valuable hitter with an OPS+ of 143 in the year of the pitcher. Whitey Ford had retired, Roger Maris and Elston Howard had been traded. Mantle was the last relic of the Casey Stengel-Yogi Berra dynasty.

During that year Burke joined a small group of owners called the Young Turks who were determined to get rid of the feckless Commissioner William Eckert. Their successful coup angered Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, baseball’s behind-the-scenes power and an Eckert supporter.

Burke’s name emerged as a candidate for commissioner. Although he maintained he didn’t want the job, he gave a reflective interview to the New York Times that sounded like a campaign speech. He acknowledged that the game was in trouble — public opinion polls showed that football had surpassed it as the most popular sport — but he cautioned against tampering with the basic rules. “Baseball essentially is a nonviolent sport in a violent time,” he said. “But it’s absolutely fundamental to man’s nature — one man with a bat facing one man with a ball.”17

In a marathon meeting on December 21, most American League clubs voted for Burke while the National League, led by O’Malley, lined up behind Chub Feeney, vice president of the Giants. Before the meeting adjourned around 5:00 the next morning, Burke withdrew his name. “I couldn’t imagine working for 25 O’Malleys,” he wrote later. “Or even one.”18 It’s hard to imagine baseball owners in 1968 choosing a longhaired outsider as their leader.

From his first days as president, Burke saw that Yankee Stadium needed rebuilding as badly as the team on the field. Crumbling concrete, stinking restrooms, and four decades’ accumulation of gunk had brought the treasured landmark close to ruin. New York Mayor John Lindsay agreed to have the city buy the stadium and pay for an extensive renovation, over opposition from some of his own staff and members of the city council. Burke never threatened to leave town; he didn’t have to. The NFL Giants had already announced their move to a new stadium in the New Jersey Meadowlands. Keeping the Yankees in the Bronx was a political necessity.

By 1970, the fourth year of MacPhail’s five-year plan, the Yankees had grown a new generation of stars in rookie catcher Thurman Munson, center fielder Bobby Murcer, left fielder Roy White, and pitchers Mel Stottlemyre and Fritz Peterson. They soared to 93 victories and a second-place finish in the AL East, although they trailed 15 games behind Baltimore. But the fans did not come back. In 1972, as the team hung in the race for the division championship until the final days, attendance dropped below 1 million for the first time since World War II.

The Yankees had made a profit for CBS only once in eight years while losing a reported $11 million. Some network executives thought the club’s also-ran performance was tarnishing the CBS brand. “Paley was tired of it,” Burke said.19

The chairman told him, “Offer me a fair price and it’s yours.”20 Burke went trolling for money. When he found it, he bought trouble.

Gabe Paul, president of the Cleveland Indians, put Burke together with George M. Steinbrenner III, who had inherited a shipbuilding company and was growing it into a dominant force in shipping on the Great Lakes. Now he was shopping for a baseball team. Burke told him Paley’s asking price was $10 million, $3.2 million less than CBS had paid for the franchise. Within weeks Steinbrenner assembled an investor group and closed the deal. Burke was awarded a 5-percent share as a finder’s fee.

Steinbrenner and Burke introduced themselves as co-general partners at a press conference on January 3, 1973. Steinbrenner said he would be an absentee owner: “I’ll stick to building ships.”21 On Paley’s orders, Burke told the media that CBS had broken even because of the tax deductions it gained from owning the team. “Bill Paley was determined not to have it look like a bad deal,” he explained later.22 Steinbrenner blew up that rationalization, and enraged Paley, when he declared, “This is the best bargain in baseball.”23 The purchase price was less than Bud Selig had paid for the bankrupt Seattle Pilots three years earlier.

The events that led to Burke’s departure raised another controversy. “When we bought the team, there was no question that I was going to run it,” Burke said. “Gabe Paul was supposed to help out in the front office for a couple of years and then retire to Florida.”24

Paul said that was “a baldfaced lie.” In his version, he, Burke, and Steinbrenner had agreed that he would be in charge: “The three of us were sitting in the back of the car and we shook hands on it, we put our hands on top of each other like football players before a game.” Paul added, “Mike Burke ought to get down on his knees when George Steinbrenner’s name is mentioned. He ought to thank the good Lord for George Steinbrenner. Mike Burke owns 5 percent of the New York Yankees, and do you know how much that cost him, thanks to George Steinbrenner? Nothing, not a plug nickel.”25

Paul was still working for Steinbrenner when he unleashed that diatribe in 1977. However, at the press conference announcing his purchase of the team, Steinbrenner had said, “Mike will be in complete charge.”26 Burke loved being president of the Yankees and the spotlight that came with it. He never would have allied with Steinbrenner unless he was assured of keeping his job.

Soon there was no question about who was running the show. On Opening Day at the stadium, the absentee owner wrote down the uniform numbers of several players and demanded that they get haircuts. (Their hair probably was no longer than Burke’s.) Steinbrenner had berated Burke for signing Bobby Murcer to a $100,000 contract. When Murcer struck out with the tying run on base, Steinbrenner bellowed, “There’s your goddamn hundred-thousand-a-year ballplayer!”27

“He shouted and blustered from a lack of fundamental self-assurance,” Burke said. He believed Steinbrenner had lied to him about Gabe Paul’s role and had tried to renege on the promise of a 5-percent share. “From the very first George had been bugged by my New York visibility and the amiable relationship I enjoyed with a variety of people,” Burke wrote.28

He resigned three weeks after the opener, becoming the first of many who found Steinbrenner unbearable. He told friends, “I’ll be fine when I get this knife out of my back.”29 He retained his 5-percent stake and, according to Paul, a consulting contract at $25,000 a year. Not that he was ever consulted.

In spite of the sour ending, Burke recalled his Yankee years as “a long, lilting holiday.”30 The job had brought him rich and powerful friends in the highest echelons of New York society and made the onetime undercover agent famous.

Burke’s business resume consisted of presiding over the decline and fall of Ringling Brothers, losing money with the Yankees, picking the wrong partner in Steinbrenner, and being maneuvered out of his job. Yet he landed a new plum position as head of another marquee New York institution. The conglomerate Gulf & Western hired him to be president of its Madison Square Garden subsidiary. “I couldn’t care less about Mike’s Yankee record,” G&W president Jim Judelson said. “I picked Mike for his chemistry, his image, his entrepreneurial skills.”31 Burke said the company’s chairman, Charles Bludhorn, was the one who hired him, but the mercurial Bludhorn evidently paid no attention to his track record, either.

Besides the storied arena, which was operating at a loss, Burke’s portfolio included the Holiday on Ice show and two teams going downhill, the NBA Knicks and NHL Rangers. He boosted revenue by booking more rock concerts, hosting the 1976 and 1980 Democratic National Conventions, and promoting the second Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier fight and Ali’s heavyweight title bouts against Ken Norton (held at Yankee Stadium) and Earnie Shavers.

With the decline of the Knicks and Rangers, there were persistent rumors that Burke would be fired. A bartender, that familiar sage of the sports pages, complained, “What did he ever do but take winners and turn them into losers?”

“Burke is the quintessential nice guy whose teams finish last, or close to it, while he moves onward and upward,” writer Sidney Zion observed. In the face of mounting criticism, Zion noted that Burke was still the sportswriters’ favorite, had the right friends, and went to the right places, “likely to be seen with one or another young lovely on his arm.”32

Burke lasted at the Garden for eight years, longer than he held any other job. He resigned, apparently voluntarily, in 1981. Now 65, he retired to his 500-acre farm in County Galway, Ireland, the home of his ancestors. He spent the rest of his life as a country squire, riding horseback every day while wearing a Pittsburgh Pirates cap for some unexplained reason. Burke’s ex-wife Timmy was with him when he died of cancer at 70 on February 5, 1987.

What is left, like the Cheshire cat’s smile, is the charm. Even Steinbrenner fell for it, calling Burke “a real heartthrob kind of guy.”33 His friend Howard Cosell eulogized him: “He was a civilized man in an era extremely short on civility and civilization.”34 The charmer had led a charmed life.

Acknowledgments

Photo credit: Associated Press. This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Baseball-reference.com

Armour, Mark. “Lee MacPhail.” SABR BioProject.

Corbett, Warren. “Gabe Paul.” SABR BioProject.

Vorperian, John. “Ralph Houk.” SABR BioProject.

Notes

1 Mike Lupica, “A Life of Daring and Caring,” New York Daily News, February 7, 1987: 40.

2 Published accounts give several different birthdays. The June 8 date was provided by the town clerk’s office in Enfield, Connecticut, the keeper of the official records.

3 Michael Burke, Outrageous Good Fortune (Boston: Little, Brown, 1984), 136. Many details of Burke’s life and his undercover work come from this autobiography.

4 Ben McIntyre, A Spy Among Friends (New York: Crown, 2014), 140.

5 Burke, 166.

6 Robert Weintraub, “Yankee Executive, Soldier, Spy,” Grantland, May 6, 2015. http://grantland.com/features/mike-burke-new-york-yankees-team-president-spy-world-war-two-baseball-mlb/, accessed April 2, 2019. The letters were released to the public 41 years later under the Freedom of Information Act.

7 Sally Bedell Smith, In All His Glory: The Life of William S. Paley (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 439.

8 Burke, 229.

9 Smith, 439.

10 “Yanks Sale to CBS Pales Black Sox Scandal,” New York Daily News, August 16, 1964: 117.

11 Joseph Durso, “CBS Tells of Plans for Yankees,” New York Times, December 26, 1965: S12.

12 Sidney Zion, “The Troubled World of Mike Burke,” New York Times Magazine, October 9, 1977: 86.

13 Philip Bashe, Dog Days (New York: Random House, 1994), 88.

14 Burke, 243.

15 Marty Appel, Now Pitching for the Yankees (Toronto: Sport Media Publishing, 2001), 55-56.

16 Smith, 441.

17 Durso, “Baseball Speculation Focusing on a Wary Burke,” New York Times, December 15, 1968: S1.

18 Burke, 283.

19 Zion, 88.

20 Ibid.

21 Durso, “C.B.S. Sells Yankees for $10 Million,” New York Times, January 4, 1973: 45.

22 Smith, 489.

23 United Press International, “Yankees Sold for $10 Million,” Daily Record (Long Branch, New Jersey), January 4, 1973: 24.

24 Zion, 89.

25 Ibid., 91.

26 “Burke Finally Gets Wish,” Passaic (New Jersey) Herald-News, January 4, 1973: 33.

27 Burke, 320.

28 Ibid., 321.

29 Appel, 137.

30 Burke, 284.

31 Zion, 92.

32 Ibid., 32, 94.

33 Weintraub.

34 Howard Cosell, “Mike Burke: A Great Man Who Cared,” New York Daily News, February 11, 1987: 31.

Full Name

Edmund Michael Burke

Born

June 8, 1916 at Enfield, CT (US)

Died

February 5, 1987 at , Galway (Ireland)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.