New York Yankees team ownership history

This article was written by Mark Armour - Daniel R. Levitt

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

In over a century of existence, through 2016 the New York Yankees have been run by only five different ownership groups.1 To their great fortune and that of their fans, the three longest tenured were well-capitalized and committed to winning. They also had a terrific knack for finding great baseball men to work for them. During these three ownership regimes the Yankees (as of 2017) have won a record 40 American League pennants and 27 world championships.

New York Enters the American League

American League President Ban Johnson knew that for the long-term success of his new major league, which began in 1901, he would eventually need a franchise in New York. Among his circuit’s four Eastern clubs — Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington — Baltimore was Johnson’s preferred candidate for relocation: It was smaller than Boston and Philadelphia, and he liked having a team in the nation’s capital. Though many of Baltimore’s syndicate of owners were locals who considered their city major league-caliber — the Baltimore National League squad of the mid-1890s had been baseball’s best before being amalgamated into the Brooklyn Dodgers — Johnson, at least as early as the 1902 preseason, had begun secretly talking with Baltimore manager John McGraw about shifting the Orioles franchise to Gotham.

Johnson’s biggest challenge to putting a team in New York would be finding a place to play. The National League’s Giants were owned by Andrew Freedman, a wealthy, well-connected real-estate tycoon, who was also a confidant of Tammany Hall boss Richard Croker.2 At the time, as urban America exploded in population, municipal governments often couldn’t cope with the influx of immigrants and rural migrants; into this vacuum stepped party organizations, often called “machines” that were run by “bosses.” These organizations doled out favors to businessmen competing for construction projects and other municipal licenses, gave city jobs to their supporters, and addressed many of the needs of working-class ethnic communities. Urban machines were notoriously corrupt but often remained in power for decades with the support of the voters and a frequently corrupt judiciary. The most notorious of these organizations, dubbed Tammany Hall, was a Democratic political machine that controlled New York City for many years.3 Freedman used his connections with Tammany Hall to block the few available suitable sites.

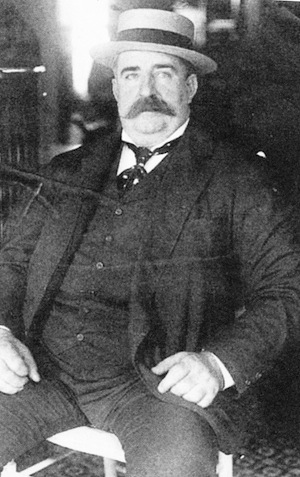

John McGraw, ambitious, driven, and mercurial, liked the idea of running a team in the nation’s largest metropolis and covertly traveled to New York early in the 1902 season to scout out potential ballpark locations. He met with Frank Farrell, himself a well-connected Tammanyite and boss of much of the City’s high-end, illegal gambling and horse-race betting, and an associate of Tammany’s Big Tim Sullivan.4 Most famous for his palatial gambling establishment, the House with the Bronze Door, Farrell and his syndicate oversaw roughly 250 gambling enterprises. With Farrell’s support, McGraw thought they had lined up a position on the East Side around 112th Street but the city turned the site into a park, frustrating their plan.5

John McGraw, ambitious, driven, and mercurial, liked the idea of running a team in the nation’s largest metropolis and covertly traveled to New York early in the 1902 season to scout out potential ballpark locations. He met with Frank Farrell, himself a well-connected Tammanyite and boss of much of the City’s high-end, illegal gambling and horse-race betting, and an associate of Tammany’s Big Tim Sullivan.4 Most famous for his palatial gambling establishment, the House with the Bronze Door, Farrell and his syndicate oversaw roughly 250 gambling enterprises. With Farrell’s support, McGraw thought they had lined up a position on the East Side around 112th Street but the city turned the site into a park, frustrating their plan.5

McGraw and Johnson, however, couldn’t coexist in the same league. One of Johnson’s key tenets in starting his new league had been to clean up the hooliganism, dirty play, and umpire abuse that had been rampant in the National League during the 1890s. McGraw, aggressive and willing to do just about any of those now-forbidden deeds to win, was suspended several times early in the 1902 season for his abusive actions. Upon the last suspension McGraw later claimed Johnson told him that he would not be allowed to stay on as manager of the team when it moved to New York.6

Shortly thereafter McGraw entered secret negotiations with Freedman and two engineered a scheme to get McGraw to New York and deal the AL a significant blow. In July, McGraw contrived to get released from his Baltimore contract and was promptly signed by Freedman to manage the Giants. Freedman, using a front man to purchase the stock, then acquired a controlling interest in the Baltimore franchise and released all the team’s capable ballplayers, who were then scooped up by the Giants. Johnson, who had some inkling of the plan and was not altogether taken by surprise, quickly grabbed back control of the franchise and cobbled together a roster to play out the season.7

If he hadn’t been fully committed before, Freedman’s treachery cemented Johnson’s determination to field a team in New York in 1903. The league voted in August to stake the up-front costs necessary to plant their flag in Gotham for the next season, a price that included signing a number of players from the National League’s Pirates. Of course, as emissary for his league Johnson faced two significant hurdles: He needed to find a well-heeled ownership group he liked, and he needed a place to play. And the two were not unrelated: Though Freedman had sold the Giants in September 1902, because of his enmity with Johnson and his support for the NL, he continued to use his connections to block the American League’s search for suitable stadium locations. His influence over land sites and their potential assemblage through his association with the Interborough Rapid Transit system only added to the new league’s difficulties. Johnson’s dilemma became fully apparent when a site he thought he had assembled at 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue was blocked, apparently due to the influence of Freedman.8 Fortunately for Johnson, he was sought out by Joseph Gordon, a coal merchant with some history in New York baseball. Gordon had just lost his job as deputy superintendent of buildings and was well plugged into New York City real estate. Gordon claimed he knew of an available site. In return he wanted the franchise. Johnson, though he needed the site, recognized that Gordon didn’t have the wealth to build and run a franchise in Gotham and insisted on “seeing the man with the money.” Gordon introduced him to Frank Farrell, still excited about owning a baseball team and also feeling betrayed by McGraw, though Farrell and Johnson had conceivably met previously through influential New York Sun sportswriter Joe Vila.9 Farrell purportedly showed up with a certified check for $25,000. When he proved amenable to paying both $18,000 to cover salaries advanced to players by the league and some nominal reimbursements to Baltimore’s minority stockholders, and willing to spend the funds necessary to build a ball grounds and assemble a team, Johnson awarded Farrell the franchise. Farrell also assured him he didn’t have to bring in any partners: “I didn’t propose to let anybody carve me if I went into this thing.” The AL president, who prided himself on being squeaky clean, had little choice but to accept a well-connected Tammanyite of his own. To front for the franchise, Farrell and Johnson allowed Gordon, generally unconnected to Tammany Hall, to act as team president.10

On March 14, 1903, the Greater New York Baseball Association was incorporated to operate New York’s American League baseball franchise. Gordon was clearly the face of the new team, and several days later he publicly announced the stockholders, who included Farrell.11 The AL Baltimore franchise ceased to exist.

Despite Farrell’s earlier protestations, he brought in his longtime friend Big Bill Devery as a partner. Devery was a shady ex-police chief with his own Tammany connections, who had escaped conviction despite a couple of indictments. Devery had walked the beat of one of Farrell’s first gambling parlors and the two had been friends ever since. Devery had accumulated a nice nest-egg by 1903 but had lost his position and clout within the Tammany political machine. Devery’s connection with the team remained obfuscated for many years and for a short time he even denied being an owner. Farrell later became the face of ownership, and over time his press became more sympathetic, focusing on baseball, not his gambling connections. He was now a “sportsman,” not a “gambler.”12

Despite Farrell’s earlier protestations, he brought in his longtime friend Big Bill Devery as a partner. Devery was a shady ex-police chief with his own Tammany connections, who had escaped conviction despite a couple of indictments. Devery had walked the beat of one of Farrell’s first gambling parlors and the two had been friends ever since. Devery had accumulated a nice nest-egg by 1903 but had lost his position and clout within the Tammany political machine. Devery’s connection with the team remained obfuscated for many years and for a short time he even denied being an owner. Farrell later became the face of ownership, and over time his press became more sympathetic, focusing on baseball, not his gambling connections. He was now a “sportsman,” not a “gambler.”12

Even with their Tammany and real-estate connections, the New York club could do no better than Gordon’s marginal site just west of Broadway between 165th and 168th Streets at the far north end of Manhattan in Washington Heights. It was leased for a 10-year term from the New York Institute for the Blind. The lease was executed on March 12, 1903, giving the team only seven weeks to build the ball grounds in time for the April 30 home opener. Fortunately, the erection of the modest wood-frame stands of the era could be accomplished relatively quickly.13 As a backup Johnson and the new owners had identified a site in the Bronx owned by the Astor estate at 161st Street and Jerome Avenue — a site that two decades later would be purchased by a different set of Yankees owners for a new stadium.14

Still, getting the ballpark built in time would be a close race due to the physical configuration of the location. The work to level and prepare the rocky, uneven site cost roughly $200,000, while construction of the 16,000-seat ballpark cost approximately $75,000, bringing the total investment for Farrell and Devery in the their new grounds to around $275,000, an outlay larger than typical for ballpark erection at the time, though they may have received some assistance from the league.15 The ball grounds were christened Hilltop Park and the team became informally dubbed the Highlanders because the location was one of the highest points on Manhattan and Gordon’s Highlanders (in an allusion to the team’s president) were one of the most famous regiments in the British Army.16

New Yorkers did not immediately flock to see their new American League entry. Despite a sold-out Opening Day, the team drew just over 210,000 fans, the second lowest in the league and well behind their crosstown rival Giants, but turned a small profit. The team more than doubled its attendance in 1904 as the Highlanders were in the pennant chase until the last day of the season. Over the next several years the club generally fell in the middle of the league in attendance, and while financial information is sketchy, when the Highlanders finished second in 1910 with mediocre attendance, they reportedly turned an $80,000 profit.17 In part, this was because Farrell abandoned his pledge of no advertising in Hilltop Park and sold billboard space on the outfield fences.18

In 1907 Farrell bounced President Gordon and took over the role himself, explaining, “I decided that I should get some of the glory. I had put up the money and done a lot of the work.”19 Gordon had snagged much of the spotlight late in the 1904 season when he chided the NL champion Giants for their reluctance and subsequent refusal to participate in the World Series against the upstart American League. As the publicity available to a baseball owner in New York became more apparent, Farrell no longer wanted to remain in the background. When he let Gordon go, Farrell offered his one-time president the dividends on $10,000 worth of stock, but no right to sell, transfer, or vote the stock.20

Gordon refused to go quietly. He claimed he had been promised a 50 percent share of the team when originally incorporated and that he was due half the profits after Farrell received the return of his initial capital. He also claimed that the team had been making significant profits based on recent average revenues of $240,000 and expenses of $80,000; accordingly, he demanded an accounting, as the rightful beneficiary of half of these profits.21 It’s highly unlikely the team was anywhere near as profitable as Gordon alleged, and in the end the court ruled against his improbable, undocumented claim for half the franchise.22

In 1909, as teams throughout baseball began opening the next generation of concrete-and-steel ballparks, Farrell resurrected his search for a suitable location for a new ballpark. Moreover, the New York Institute for the Blind seemed reluctant to extend the land lease, which would expire prior to the 1913 season. For a new, modern ballpark, Farrell and his proxies uncovered a site in the Bronx just north of the Harlem Ship Canal. The overall area under the land assemblage included the old Spuyten Duyvil Creek and surrounding marshy regions. Dewatering this site sufficiently to allow the construction of new ballpark would prove an engineering nightmare.23 Nevertheless, Farrell outwardly expressed optimism. “In my new site,” he said, “I believe I have secured an excellent location, and I shall erect a series of stands that will afford spectators every comfort and convenience that the up-to-date baseball fan has learned to expect as his right. It will be fireproof, which in itself will relieve every officer of the club of much worry and responsibility.”24

Early in the 1911 season Farrell had a chance to offer a courtesy to his crosstown rivals when the Giants ballpark, the Polo Grounds, suffered significant fire damage. Farrell offered up Hilltop Park to accommodate the Giants games until the Polo Grounds repairs were finished. When the Giants moved back into the rebuilt Polo Grounds in late June, Giants owner John Brush would remember the consideration shown by Farrell.

Despite the outlay of considerable sums on engineering his new ballpark in the Bronx, Farrell’s project was plagued with water and construction difficulties, sapping much of his focus and energy from his team on the field. Moreover, Farrell proved a poor judge of baseball executive acumen and integrity. Late in the relatively successful 1910 season he sided with crooked star first baseman Hal Chase over manager George Stallings, bouncing the latter and installing Chase as player-manager. After one season, Farrell replaced Chase with the overmatched Harry Wolverton; Chase remained as the first baseman, and the team struggled on the field.

The ballpark situation, too, remained an ongoing headache. With their 10-year lease nearing expiration and the New York Institute for the Blind unwilling to renew it — thinking they could get more than the $10,000 per year the Highlanders were paying — Farrell needed a new venue quickly. Fortunately for Farrell, Brush allowed the Highlanders to share the Polo Grounds. Under the terms the new lease, the team paid the Giants $55,000 a year for the first two years, and the Giants were responsible for maintenance and expenses. The AL club would also be allocated a small share of the concession revenue.25 After 1910 with the team consistently in the second division, the losses associated with the Bronx stadium fiasco, and now having to pay significantly higher rent, Farrell and Devery were beginning to feel the financial pinch.

The Two Colonels Take Over

In 1914 Organized Baseball was challenged by a new competitor when the upstart Federal League declared itself a major league. Both the major and minor leagues as well as the Federal League suffered huge financial losses during the two-year conflict. As the leagues battled for players over the winter of 1914-15, Ban Johnson and Federal League President Jim Gilmore both understood the importance of shoring up their league’s weakest franchises, and both wanted the same man for a New York franchise, Jacob Ruppert. One of New York’s most eligible bachelors, Ruppert ran his family’s brewery operation and had accumulated a significant fortune. Well dressed and at home in upper-class society, Ruppert occasionally lapsed into a German accent when agitated, despite his native birth. Ruppert also dabbled in exotic hobbies: He collected jade, Chinese porcelain, and oil paintings; for a time he kept a collection of small monkeys, and he raised Saint Bernards. Like many of the upper class at the turn of the last century, he also raised and raced horses.26

In 1914 Organized Baseball was challenged by a new competitor when the upstart Federal League declared itself a major league. Both the major and minor leagues as well as the Federal League suffered huge financial losses during the two-year conflict. As the leagues battled for players over the winter of 1914-15, Ban Johnson and Federal League President Jim Gilmore both understood the importance of shoring up their league’s weakest franchises, and both wanted the same man for a New York franchise, Jacob Ruppert. One of New York’s most eligible bachelors, Ruppert ran his family’s brewery operation and had accumulated a significant fortune. Well dressed and at home in upper-class society, Ruppert occasionally lapsed into a German accent when agitated, despite his native birth. Ruppert also dabbled in exotic hobbies: He collected jade, Chinese porcelain, and oil paintings; for a time he kept a collection of small monkeys, and he raised Saint Bernards. Like many of the upper class at the turn of the last century, he also raised and raced horses.26

Popular, wealthy, and well-connected to the German-American community, Ruppert was a natural for politics. In 1886 he joined an upper-class regiment of New York’s National Guard. A few years later he was appointed aide de camp to Governor David Hill and given the rank of colonel, a largely ceremonial title. Ruppert took great pleasure in this title and for the rest of his life liked to be addressed by it.

Late in the 1880s Tammany Hall tapped Ruppert to run for city council president, but they withdrew his candidacy due to various political machinations and miscalculations. The Democratic organization later sponsored him to run for the US Congress in 1898 in a generally Republican district. Ruppert won in a mild upset and served four terms. After eight years in Congress, Ruppert concentrated most of his energies, aside from all his hobbies, on the brewery business. Moreover, Ruppert had loved baseball since his youth. In 1914 Ruppert began talking to people in and around baseball, inquiring about buying into the game. Both Gilmore and Johnson remained in close touch with Ruppert, hoping to entice him into his league.

Johnson’s mortal enemy, New York Giants manager John McGraw, may have inadvertently helped Johnson in his quest. McGraw was a close friend of Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston, another wealthy investor looking to buy into baseball. An engineer by training, Huston had remained in Cuba after fighting in the Spanish-American War and started an engineering and construction company. By 1914 he was a rich man, near the level of most baseball owners, but well below Ruppert’s fortune. Huston reportedly secured an option to purchase the Chicago Cubs for $600,000 in 1914 and planned to bring along his pal McGraw as manager and part-owner. McGraw initially expressed an interest but soon claimed he was tied to New York by his multiyear contract.27 In reality, he probably did not want to leave New York and simply wanted an excuse so as not to embarrass his friend. Without McGraw on board, Huston allowed the option to lapse.

Ruppert and Huston did not know each other but the baseball ownership fraternity was small, and once they met — probably through McGraw — the two agreed to join forces for the right opportunity. McGraw suggested that the Yankees might be available, and the two reluctantly agreed to look into what was generally regarded as one of baseball’s most hapless teams. Adding to their trepidation, the team’s books were a mess and Ruppert and Huston were more than a little leery about what they were getting into.

In Johnson’s eyes, though, the Yankees were the perfect franchise for the duo. Ruppert was a well-connected New Yorker without too much Tammany baggage, and Frank Farrell and William Devery, always of suspect character, were out of money. As an inducement, Johnson persuaded the American League’s owners to make some decent players available to the Yankees immediately after the two gained control the club.

Farrell, however, didn’t really want to sell the Yankees. He liked all the perks that came with owning a major-league baseball team in New York. Farrell dragged out the sale by lingering over minor contractual matters in the hope that something might change. The team had accumulated losses of $83,273 and debts of around $285,000, however, and his partner, William Devery, who generally liked to stay behind the scenes, was ready to cash out.28

In late 1914, while Ruppert was reconsidering, Gilmore and Chicago Federal League owner Charles Weeghman traveled to French Lick, Indiana, the resort community where Ruppert spent a portion of his winters. They hoped to tempt Ruppert into purchasing the Indianapolis franchise, which he would move to New York or its environs.

Once Ban Johnson realized how close the Federals were to landing Ruppert, he snapped back into action. On Saturday, January 30, 1915, as negotiations remained stalled, Johnson had finally had enough of Farrell’s procrastination. He put Farrell and Devery in one conference room, Ruppert and Huston in another, and trusted the lawyers to hammer out the final document. In the end the new owners closed on the team for $463,000.29

Once they purchased the franchise, their fellow American League magnates generally forgot their pledge to make players available to the Yankees. Only Detroit President Frank Navin honored the promise of players: He allowed the Yankees to purchase two reserves, outfielder Hugh High and first baseman Wally Pipp, for $5,500. In July, the team purchased budding star pitcher Bob Shawkey for only $3,000 from Philadelphia Athletics owner Connie Mack, who, in a financial bind because of the Federal League, was selling players. In another arrangement to find players, Ruppert reached an agreement with Richmond in the International League through which for a payment of $3,000 the Yankees would get first dibs on selecting any player they wanted from the Richmond roster for the payment of an additional $2,500 per player.30

Resentful but still determined, Ruppert and Huston hoped to purchase some of baseball’s better players as they became available in the aftermath of the Federal League war. They spent $40,000 to purchase four mediocre players controlled by Federal League magnate Harry Sinclair. More successfully, they paid Mack $37,500 for future Hall of Fame third baseman Home Run Baker, who had held out during 1915 while demanding his contract be renegotiated. The Yankees owners felt frustrated and further betrayed that same offseason at their exclusion from the Tris Speaker sweepstakes when Ban Johnson engineered the sale of the all-time great center fielder from Boston to Cleveland for $55,000.

Huston hoped to prove his baseball smarts as a front-office executive and actively supervise baseball personnel decisions on the model of Charles Comiskey in Chicago or Barney Dreyfuss in Pittsburgh. Unfortunately for Huston, in one of his first high-dollar recommendations the Yankees purchased pitcher Dan Tipple from Indianapolis for $9,000 — a considerable sum for the time, particularly in the midst of the Federal League war. Tipple’s failure to perform and progress as expected led quickly to Huston’s eclipse as a baseball insider.

The partnership of Huston and Ruppert was strained from the start. Neither man had the temperament or desire to share authority. Nevertheless, the Two Colonels both tried hard — and with some success — to make the marriage work. Both were extremely competitive and driven. Ruppert played the hard-driving perfectionist, while Huston was the high-spirited, socially active partner. The Yankees hired Wild Bill Donovan as their manager but let him go after three years at the helm on the heels of a 71-82 finish in 1917. Huston wanted to hire his buddy and current Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson. Ruppert, who did not really know Robinson, interviewed him and came away unimpressed. Furthermore, signing Robinson would have caused some friction with Dodgers owner Charles Ebbets, though the Yankees could have maneuvered through this had Ruppert really wanted Robinson.

Huston, who had joined the war effort and was in France (he would return a lieutenant colonel, leading many to call the owners the Two Colonels), could not exert the influence he wanted or deserved. Ruppert remained resistant to Robinson and consulted Ban Johnson for advice. Johnson reportedly recommended the St. Louis Cardinals’ diminutive manager, Miller Huggins, whom he considered the best manager in the National League behind John McGraw. Ruppert was favorably impressed with Huggins and hired him without consulting Huston. Huston was naturally furious that while he was away, Ruppert had spurned his candidate and signed another. Ruppert’s unilateral hiring of Huggins led to the most serious and longest-lasting disagreement between the two owners. Huston’s anger at the Huggins hiring ripened into an excessive dislike of Huggins and a hatred of Johnson for his perceived interference with his team’s internal affairs. Even after he returned from France, Huston never reconciled himself to Huggins. Until he sold out his interest in the Yankees a number of years later, Huston unrelentingly worked to undermine and replace him.

In the middle of 1919 the Yankees owners found themselves at the center of a controversy that would eventually topple the National Commission, baseball’s ruling body. Carl Mays, one of the American League’s top pitchers, jumped the Red Sox in July, and, as the other league owners began offering packages of players and money for Mays, Boston owner Harry Frazee looked to cash in. Johnson argued that an insubordinate player should not be able to force a trade and demanded that the Red Sox instead suspend Mays. Frazee and the Two Colonels ignored Johnson’s edict: The Yankees bought Mays for $40,000 and two players. Johnson ordered Mays suspended and decreed that he could not play for New York. The Yankees owners disregarded Johnson’s directive and obtained a court injunction permitting Mays to play. With this act of defiance, the Yankees owners, allied with Frazee, became the focus of Johnson’s enmity. Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, also feuding with Johnson, joined Frazee and the Yankees owners in a triumvirate committed to the dismissal, or at least neutering, of Johnson — first among equals on the three-man National Commission.

The other five American League owners, however, remained loyal to Johnson, creating a precarious stalemate. Albert Lasker, a prominent Chicago businessman and a Cubs minority stockholder, proposed a plan to replace the old Commission system with a three-person triumvirate of neutrals with no financial interest in baseball. The National League generally supported the plan, but the five Johnson loyalists in the American League objected, mainly because Johnson would be forced to relinquish his power. After much posturing and politicking, the issue came to a head in November. At a meeting in Chicago on August 8, the three disgruntled American League franchises threatened to jump to the National League, forming a 12-team New National League. (Another team would be added later.) The Johnson loyalists eventually backed down, and the owners brought in Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis as baseball’s first commissioner.

The Yankees owners continued their big spending after the 1919 season when they splurged for Babe Ruth. With the financial squeeze mounting on Boston owner Harry Frazee, on January 5, 1920, the Yankees and Red Sox announced the sale of Ruth from Boston to New York. The Yankees paid a record sum of $100,000: $25,000 up front and three promissory notes of $25,000, each at a 6 percent interest rate, due in November 1920, 1921, and 1922. In addition, Ruppert gave Frazee a three-month commitment that he would lend him $300,000 to be secured by a first mortgage on Fenway Park.31

Notably at this time, the constitutional amendment banning the sale of alcoholic beverages was taking effect. The new law would clearly have a significant adverse impact on Ruppert’s brewery operation — his main source of income. The purchase of Ruth and the large loan to Frazee testified to Ruppert’s willingness to take considerable financial risks in order to construct a winner.

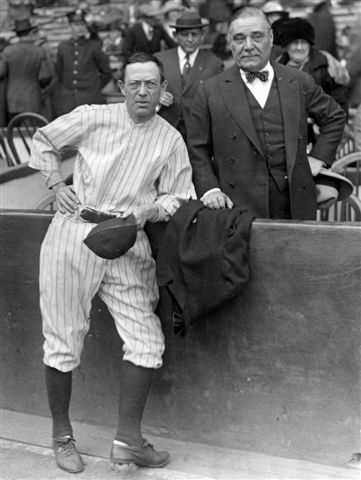

Yankees co-owner Jacob Ruppert, left, with manager Miller Huggins, and star outfielder Babe Ruth. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

With Ruth on board, in 1920 the Yankees produced one of their best seasons to date and with 1,289,422 fans set an attendance record that would stand nearly a decade. Sustained by the Babe’s heroics, Huggins led the Yankees to 95 wins and a third-place finish. The team was on the cusp of greatness with owners willing to spend.

When business manager Harry Sparrow died in May 1920, the two owners were forced to take on a larger hands-on role that they didn’t really want. Moreover, as the owner of a large brewery operation, Ruppert recognized the importance of sound oversight and professional administration. After the season they reached out to Ed Barrow, manager of the Boston Red Sox, to oversee their front office. Technically hired as business manager, Barrow was one of the first men to take on the role of the modern general manager. A brilliant hire, the introduction of this new front office position, and Barrow’s grasping of both its potential and its boundaries was one of the foundations of the coming Yankees dynasty.

Barrow also introduced another of the keys to the Yankees long-term success, amassing possibly the greatest assemblage of scouts in baseball history. During his tenure Barrow expanded and reorganized his scouts, creating arguably the first modern scouting department. He hired Vinegar Bill Essick to scout the West and Eddie Herr, a former Detroit Tigers scout, whom he assigned to the Midwest. Bob Gilks and Ed Holly focused on the South and East respectively. Superscout Paul Krichell was principally responsible for the colleges, and acted as Barrow’s right hand.32

Through their relationship with the cash-strapped Frazee, the Yankees owners had a unique pipeline to major-league talent. Ruppert was willing to part with his money for top talent, and Frazee was more than happy to sell his remaining stars. That offseason the Yankees sent $50,000 and a couple of players to Frazee for four players including Hall of Fame hurler Waite Hoyt and star catcher Wally Schang. In 1921, with this new talent on board, a historic season from Ruth and a league-leading 27 wins from Mays, the Yankees finally won their first pennant. Although they lost the World Series to the Giants, the pennant represented vindication for all the effort and money expended by the two owners.

Over the next several years Ruppert bought the rest of Frazee’s stars. In one transaction after the 1921 season, he and Huston acquired two of the league’s best pitchers, Sam Jones and Joe Bush, along with star shortstop Everett Scott, for four players and $150,000 — the highest dollar amount ever included in a player transaction up to that point and one that would not be exceeded until the Cubs bought Rogers Hornsby from the Boston Braves near the end of the decade. In total the Yankees owners paid Frazee roughly $450,000 over a five-year period to build the team that captured three straight pennants from 1921 to 1923.

Ruppert and Huston could afford to spend because profits for the Yankees exploded after the Great War. The overall jump in baseball attendance coupled with the legalization of Sunday baseball in New York in 1919 and a Yankees ticket-price increase led to profits averaging $300,000 per year in 1920 and 1921, though much of this was paid to the government as part of the wartime excess profits tax controls. Once the tax was repealed in1921, the Yankees owners could keep more of their profits, which exceeded $300,000 in 1922.33

Furthermore, Ruppert and Huston were not taking distributions from their franchise; they were reinvesting all the profits. From 1920 through 1924, for example, four American League clubs distributed at least $200,000 to their owners, reducing the funds available for investing in minor-league talent. In contrast, the Yankees plowed over $1.6 million in profits back into the franchise; no other American League team retained even $700,000.34

The disappointment over the 1922 World Series debacle prompted the final divorce of the Two Colonels. The hated crosstown Giants swept the Series in four games, with hurler Bullet Joe Bush openly disrespecting Huggins during the final game, convincing Huston that the manager could not control his players. Back at the Commodore Hotel after the game, Huston let out a wild yell, sending drinks and glasses flying with a wide sweep of his right hand and bellowing: “Miller Huggins has managed his last Yankee ballgame. He’s through! Through! Through!” When tracked down for his reaction, Ruppert backed Huggins, announcing, “I won’t fire a man who has just brought the Yankees two pennants.”35

As long as the Yankees were unmistakably New York’s second team, Giants manager John McGraw was happy to allow his friends Huston and Ruppert to lease his home ballpark. Owner Charles Stoneham, too, liked the income generated by the lease. With the coming of Ruth, however, the Yankees boasted the league’s biggest draw and began to win as well. McGraw and Stoneham began to have second thoughts regarding the stadium arrangement and decided they wanted the Yankees out. Ruppert also suspected that Ban Johnson hoped to see the Yankees evicted — this was at the height of the Johnson/Yankee feud — as a way to revoke their league charter, which required having a venue in which to play. In May 1920 it came out that Stoneham had given notice to the Yankees that he would not renew their lease after the season.36 He eventually relented, however, and extended the lease for another two years through 1922. Stoneham made it clear, though, that this was only a short-term accommodation unless the Yankees were permanently willing to pay an exorbitant rent.

Ruppert and Huston naturally recognized that they needed their own ballpark, and needed it soon — by Opening Day 1923. A new ballpark would obviously provide many benefits beyond simply freeing themselves from the Giants control. The club would generate the ancillary revenue associated with a ballpark at the time, including concession revenue, rent from hiring out for football games and boxing matches, and storage income. Huston estimated the annual receipts from these sources at $325,000.37

In early 1921 Ruppert announced that the club had secured an option on a site in Manhattan. He assigned Charley McManus, a one-time executive in the real-estate department at Ruppert’s brewery and current Yankees front-office employee, as the point man for the stadium project. (When it was completed, McManus became superintendent of Yankee Stadium, a position he held for many years thereafter.) As with the Yankees’ previous site searches, this one proved quite difficult as well — even without obstructions thrown up by a political machine, finding and assembling a suitably large, accessible site in New York was far from a simple task. The first and then several additional sites fell by the wayside for various reasons; the Yankees eventually struggled through six potential alternatives before finally settling on their current site in the Bronx. Ruppert and Huston purchased the majority of the site from Vincent Astor. They wrangled a key corner from a florist for only $14,000 before he discovered the true reason for the acquisition. In total the Yankee owners spent close to $600,000 to acquire the entire site, and the construction cost of Yankee Stadium totaled about $1,600,000, bringing the all-in expenditure to roughly $2,200,000.

Once construction began in April 1922, Huston, the engineer, embraced the task of overseeing its construction. To help defray the cost, the American League loaned the Yankees owners $400,000 on a 10-year term at 7 percent interest. The new stadium was clearly the preeminent and most majestic baseball venue in America and would hold this distinction for many years.38

Ruppert Takes Sole Ownership

In the wake of the 1922 World Series sweep, Huston wanted out, and Ruppert was tiring of the partnership as well. Huston was frustrated by his inability to bring in a manager he respected, and highly frustrated with Ruppert’s high-handed approach to running the ballclub. “We went into the business on a fifty-fifty partnership basis,” Huston wrote to his partner, “but now you have arrogated to yourself so much authority and doing continually so many things without consulting me that it is becoming a one man show.” Along with his frustration over Huggins, Huston resented what he considered Ruppert’s co-opting of Barrow, that the blame over the Mays imbroglio fell disproportionately on himself, and what he considered Ruppert’s overall belittlement. Regarding several payments coming due, Huston added that he was ready to ante up his share, but “I will participate in no financing whatsoever until the affairs of the club are put on a truly partnership basis.”39 Perhaps just as importantly, Huston, who was not in the same financial class as his partner, felt nervous having essentially his entire net worth tied up in the team and the new Yankee Stadium.

In the wake of the 1922 World Series sweep, Huston wanted out, and Ruppert was tiring of the partnership as well. Huston was frustrated by his inability to bring in a manager he respected, and highly frustrated with Ruppert’s high-handed approach to running the ballclub. “We went into the business on a fifty-fifty partnership basis,” Huston wrote to his partner, “but now you have arrogated to yourself so much authority and doing continually so many things without consulting me that it is becoming a one man show.” Along with his frustration over Huggins, Huston resented what he considered Ruppert’s co-opting of Barrow, that the blame over the Mays imbroglio fell disproportionately on himself, and what he considered Ruppert’s overall belittlement. Regarding several payments coming due, Huston added that he was ready to ante up his share, but “I will participate in no financing whatsoever until the affairs of the club are put on a truly partnership basis.”39 Perhaps just as importantly, Huston, who was not in the same financial class as his partner, felt nervous having essentially his entire net worth tied up in the team and the new Yankee Stadium.

As the partnership deteriorated, the Two Colonels entertained the possibility of selling the franchise, going so far as to negotiate a tentative sale for $2.5 million. When the sale fell through, Huston found a buyer for his half-interest. Ruppert, not interested in a new partner, decided to buy out Huston himself. The two negotiated a buyout of Huston’s half for $1.175 million: $450,000 in cash and the remainder in nine annual principal payments beginning in June 1925 (the first payment was for $85,000 and the remaining eight for $80,000) at 6 percent interest. The transaction was finalized in May 1923.40

With the buyout completed, Ruppert later offered Barrow the opportunity to buy a 10 percent share of the Yankees for $300,000. Barrow did not have anything close to that amount and turned to his old friend and one-time partner Harry Stevens, the concessionaire, to lend him some of the money.

In the early 1930s Ruppert quickly recognized that changes in the roster rules altered the practicality and usefulness or creating a farm system. In late 1931 he paid $250,000 for the Newark franchise in the International League, one step below the majors. In February 1932 Ruppert announced that the Yankees intended to own or control four minor-league franchises in different classifications. He hired future Hall of Fame executive George Weiss to run it, and by the mid-1930s the Yankees rivaled the Cardinals for baseball’s best farm system.41

With the onset of the Depression, profits fell off dramatically for all teams, and several suffered staggering losses. In 1933, in aggregate, American League teams lost in excess of $1 million. The Yankees’ revenue advantage slipped as well, as four teams fared better financially that dismal season. Profits declined from $271,028 in 1929 to a loss of $98,126 in 1933, yet the team’s payroll of $294,982 was still the highest in baseball. In fact no other AL team had a payroll greater than $188,000. By 1939 Ruppert’s payroll was back up to $361,471, still the highest in the game.42

In early 1938 Ruppert received treatment for phlebitis, an inflammation of the veins, in his left leg. Although the malady was not thought to be serious at the time, Ruppert was confined to his home for several days. The illness forced him to skip traveling to the Opening Day festivities for his newly acquired farm club in Kansas City. Throughout the year Ruppert struggled with the condition and its complications. On January 13, 1939, after dropping in and out of a coma for several days, Ruppert died at age 71.

Meanwhile, the struggling Brooklyn Dodgers franchise had brought in the iconoclastic Larry MacPhail to run their organization. Two new economic opportunities (or challenges) faced baseball as World War II approached: radio and night baseball. In December 1938 MacPhail announced that he was pulling out of the no-radio agreement among the three New York teams, and that he would broadcast all Dodgers games. In response to MacPhail’s decision, the Giants began to waver on their pledge. Ruppert, ill but still obsessed with his baseball team, encouraged Barrow to put the Yankees on radio as well. The Yankees and Giants always worked their schedule to minimize conflicting home dates. In the same spirit, the two agreed to team up for their radio broadcast rights in 1939. Each would broadcast only home games to minimize the risk of cutting into the other’s stadium attendance.

Not surprisingly, sponsor demand was intense for the inaugural New York broadcast rights. The two teams executed a two-year contract with General Mills for Wheaties. Procter & Gamble also signed on to pitch Ivory Soap. From the two corporate sponsors the Yankees and Giants each received $110,000. The Dodgers, in a smaller market, received $87,500 despite broadcasting road games as well. [At the time announcers did not travel on the road; they broadcast re-creations based on wire reports.] The rights fees received by the New York clubs were significantly more than those received by the other franchises, which typically ranged from $30,000 to $60,000. By midseason 1939, Yankees attendance lagged 1938 by a significant margin. Team executives suspected both radio and the New York World’s Fair for the decrease in patronage. In total, attendance fell by over 100,000 from 1938 to 1939, despite a dominant team trying for its record-tying fourth consecutive pennant.

The sponsors fared poorly as well. Overall, between 3 P.M. and 5 P.M., baseball had about a 33 percent share nationwide. In Chicago the percentage of radios tuned to baseball was estimated slightly higher. In New York, however, baseball received only a 12 percent share.43 Some of this was blamed on Yankees announcer Arch McDonald, a capable announcer from the South who may have been a little too laconic for the taste of New Yorkers. Because of the low 1939 ratings the teams voluntarily agreed to reduce their fee to $75,000. The clubs also brought in a new announcer, Mel Allen, to be the lead for both the Yankee and Giant broadcasts. For 1941 the Yankees and Giants held out for $75,000 again. But this time no sponsor could be found at that level. Neither team felt it worthwhile to put the games on for a lesser rights fee and withheld their games from radio in 1941.

In 1942 the Yankees and Giants were back on the air, and Allen returned as the lead announcer. In 1943 the two teams again failed to reach an agreement with a sponsor and neither the Yankees nor Giants games were aired that season. Finally, in 1944 Gillette stepped up as a sponsor. The Yankees would never again play a season without radio coverage.

Ruppert’s death on January 13, 1939, threw the ownership of the Yankees into flux. He left the bulk of his estate in three equal shares to two nieces and Helen Weyant. Upon learning of her inheritance, Weyant expressed surprise and trepidation. She was a longtime acquaintance and the daughter of a deceased friend. Her brother Rex had been the Yankees assistant road secretary for the past three years. Full control over the estate fell to the “executors and trustees for the lifetime of the beneficiaries, who are to receive the entire proceeds during their lives.”44 Initially Ruppert’s wealth was estimated at $40 million to $45 million, of which about 60 percent would have to be paid in estate taxes. The Yankees organization was valued at around $10 million, requiring a tax payment of $5 million to $7 million. In other words, the estate would have to monetize many of the assets to pay the taxes and distribute the value of the estate to the beneficiaries.

Ruppert had designated three trustees for the bulk of the estate: his brother-in-law, H. Garrison Sillick Jr.; his brother, George Ruppert; and his longtime attorney, Byron Clark Jr. Clark also became the estate’s executor. Ruppert had added Barrow as a fourth trustee for the Yankee corporation, and he was named the team’s president. Although the beneficiaries ultimately would command the proceeds of the estate, Ruppert left the decision-making authority in the hands of the trustees. George Ruppert sought to reassure Yankee fans that Ruppert had provided for the Yankees, and that the team’s management and operation would not change.

Almost immediately rumors of a sale emerged. Despite George Ruppert’s assurances regarding the safeguards built into Ruppert’s will, payment of the estate’s tax burden weighed heavily on the trustees.

As early as July 1939 Clark disclosed that in response to the many sale inquiries, Barrow had informally valued the organization at $7 million.45 By March 1940 Barrow felt he needed to respond to the many rumors of an impending sale: “I have had several legitimate offers for the sale of the club, which I am not at liberty to mention just now, but this is not one of them. It would take a lot of money to buy the Yankees. I estimate the club to be worth roughly $6,000,000. Anybody who has that kind of money and is ready to put it up, can buy the Yankees.”46

The price continued to fall as the tax matter dragged. The asking price was actually closer to $4 million, and the Yankees received no bona-fide offers over $2 million. Clark, George Ruppert, and Barrow were all discussing the sale with several potential suitors, including Joseph Kennedy (patriarch of the Kennedy clan), with little success. In July 1940, George Ruppert acknowledged that the franchise had been offered to Democratic Party bigwig and Postmaster General James Farley for $4 million. To line up the capital, Farley was struggling to assemble a syndicate of moneyed investors. The trustees required that he muster a down payment of at least $1.5 million. In December 1940, Clark traveled with Barrow to the winter meetings in Chicago reportedly to facilitate the sale. But raising the down payment proved more difficult than expected, and Farley’s money-raising road show dragged on for nearly a year. In the end, he could not round up the necessary funds.47

In the meantime, Ruppert’s estate turned out to be worth much less than originally estimated. The trustees placed the overall value at only $7 million, a fraction of the earlier approximation. They valued the brewery stock at $2.5 million, the ballclub at $2.4 million, real estate at $600,000, and additional disparate items at $1.45 million, including miscellaneous securities, furniture, jewelry, paintings, and a $50,000 yacht. Of course, the trustees naturally had reason to value the estate as low as possible to minimize taxes. Nevertheless, the value of Ruppert’s holdings was clearly below expectations. It turned out that Ruppert owned only a portion of the brewery stock. In the real estate he so prized, he owned only a minority position, and, furthermore, the value of many of the properties had declined during the Depression.48 Magnifying the trustees’ predicament, the taxing authorities placed a much higher value on the estate than did the trustees. For example, the government valued the baseball operation at roughly $5 million as opposed to around $2.4 million by the estate. To settle the value disagreement, the estate decided to litigate the issue, which also had the advantage of postponing any tax payment until a resolution had been achieved. Regardless of the outcome of the litigation, it was now unmistakable that either the team or the brewery would have to be sold to pay the estate tax. Because the team was more liquid than the brewery and theoretically a less stable income generator, the Yankees organization seemed the more reasonable disposition.

As the dispute dragged on, the trustees grew weary of the wrangling in which they had little financial stake, and they had no desire to oversee all the complicated negotiations. On July 29, 1941, as permitted in the trust documents, they turned the administration of the estate over to the Manufacturers Trust Company.

Barrow also had to sue the estate to preserve the rights to his 10 percent ownership in the team. The original loan from Harry Stevens to purchase his share had been amended in 1938 to reflect a principal amount of $250,000 and an interest rate of 3½ percent. In his settlement with the estate, Barrow received a 10 percent interest in the team for $305,000 under the same terms as the original agreement with Ruppert.

MacPhail Puts Together a Syndicate

After the Pearl Harbor attack and America’s entry in World War II, non-war-related economic activity quickly came to a standstill. Barrow and Manufacturers Trust both received a number of inquiries, but none at a level they felt reasonable. In 1943 Larry MacPhail, now unemployed in baseball and serving in the War Department, put together a 10-person syndicate to purchase the team. His lineup of investors included construction magnate Del Webb and sportsman Dan Topping. Topping owned the Brooklyn Tigers of the National Football League. Because the team played in Ebbets field, he was effectively a tenant of MacPhail’s once he took over the Dodgers in early 1938, and the two became friendly. When they ran into each other in California during the war — MacPhail was there on War Department business, Topping with the Marine Corps — MacPhail invited him to join his syndicate. At the time Topping was having difficulty negotiating a lease renewal with Dodgers President Branch Rickey. Assuming he could get permission from the NFL to move to Manhattan (the New York football Giants already played there), owning Yankee Stadium would give him a playing venue he could control.

After the Pearl Harbor attack and America’s entry in World War II, non-war-related economic activity quickly came to a standstill. Barrow and Manufacturers Trust both received a number of inquiries, but none at a level they felt reasonable. In 1943 Larry MacPhail, now unemployed in baseball and serving in the War Department, put together a 10-person syndicate to purchase the team. His lineup of investors included construction magnate Del Webb and sportsman Dan Topping. Topping owned the Brooklyn Tigers of the National Football League. Because the team played in Ebbets field, he was effectively a tenant of MacPhail’s once he took over the Dodgers in early 1938, and the two became friendly. When they ran into each other in California during the war — MacPhail was there on War Department business, Topping with the Marine Corps — MacPhail invited him to join his syndicate. At the time Topping was having difficulty negotiating a lease renewal with Dodgers President Branch Rickey. Assuming he could get permission from the NFL to move to Manhattan (the New York football Giants already played there), owning Yankee Stadium would give him a playing venue he could control.

MacPhail first met Webb, a Phoenix-based millionaire in the construction business, in Washington during the war. MacPhail worked as an assistant to Undersecretary of War Robert Patterson, while Webb frequently traveled to Washington to negotiate war-related construction work. At the time, Webb was considering the purchase of the Oakland Pacific Coast League team for $60,000. When MacPhail contacted him regarding the Yankees opportunity, he quickly changed his focus. Other investors included Chicago taxicab magnate John Hertz and New York sanitation commissioner Bill Carey.

Barrow hated the idea of the boisterous, aggressive and spotlight-seeking MacPhail taking control of “his” team. He went so far as to state that MacPhail would only gain control of the Yankees “over his [Barrow’s] dead body.”49

MacPhail offered $2.8 million for 96.88 percent of the stock ($2.5 million for the 86.88 percent owned by the three Ruppert beneficiaries and $300,000 for the 10 percent controlled by Barrow). The remaining 3.12 percent was owned by George Ruppert and two others. In February 1944, despite Barrow’s distaste for MacPhail, acceptance by the trust company of the offer appeared imminent. Barrow managed to delay the sale, most likely because the estate received another extension on its tax bill. Commissioner Landis helped slow MacPhail down when he ruled Hertz, who was involved in horse racing, persona non grata in baseball ownership. Landis’s edict forced MacPhail to restructure his ownership entity.50

His delay in hand, Barrow sought to drive up the price or find another buyer. But finding a willing buyer with available cash under the wartime circumstances was highly problematical. In one scheme, Barrow hoped to steer the franchise to his friend, Tom Yawkey. This plan suffered from several shortcomings, most notably that Yawkey would first have to find a buyer for his Red Sox. In addition, Yawkey’s finances were potentially in limbo due to a recent divorce. Barrow also held out hope that James Farley could reformulate his syndicate, but that idea, too, came to nothing.

With little hope of either an alternate buyer in the short term or a delay until the end of the war and a reinvigoration of the civilian economy — which still seemed a long way off — Manufacturers Trust was becoming impatient. Furthermore, Webb and Topping, both now awakened to the availability of the team and their own interest in acquiring it, continued to pursue the club. The trust company attempted to reinstate MacPhail’s original terms by contacting Webb. They let him know that the estate might now be willing to sell at the original terms. The estate was also actively selling off some of its real-estate holdings, but the war depressed prices in real estate as well. Only a fraction of the tax burden could be raised through the liquidation of real-estate assets.

Independent of Webb, Topping learned through his society connections that Manufacturers Trust was getting antsy. In late 1944, when Topping again encountered MacPhail in New York, he proposed that they try to revive the deal. MacPhail needed little prompting, and the two decided that they would simplify their proposed ownership by narrowing the syndicate to include only Webb in their reformulated venture. Topping, through his numerous connections, took the lead in contacting Barrow. Topping’s father and Harry Sillick had been friends, and through H. Garrison Sillick III, he had become friendly with Barrow’s daughter, who was married to Garrison. She acted as an intermediary and set up a meeting between Barrow and Topping. Once Barrow realized the hurriedness with which Manufacturers Trust planned to dispose of the franchise, he merely hoped to preserve as much of his legacy as possible. He met one-on-one with both Topping and Webb. With both he stressed the importance of maintaining the status quo and running a first-class, well-respected, and championship organization. Both gave him enough assurance that he could sell without too much trepidation — although he had little choice, in any case.

In late January 1945, MacPhail, Webb, and Topping finally purchased the team, split evenly so that each owned one-third. They put $250,000 down with the remainder to follow in March. Prior to their final payment, the trio also agreed to purchase George Ruppert’s and associates’ 3.12 percent interest, giving them complete ownership of the team. Webb and Topping supplied the majority of the capital, lending MacPhail much of his obligation, and MacPhail became president under a 10-year contract. The final transfer of operational control occurred in late February.

When MacPhail took over the Yankees, he was already famous within baseball circles, having run the Reds and Dodgers with some success. His fame came from his game promotions and events, his installation of lights in both cities to allow night games, and his embrace of radio. He hired the unknown Red Barber to broadcast Reds games, and later brought him to Brooklyn. MacPhail and his two partners had clearly made a good buy. Even in 1945, the financial potential of the Yankees shined through. The Yankees turned a profit of just over $300,000 on $1.6 million in revenues. Though the farm clubs showed a slight loss of just over $100,000, overall the organization made $202,000 during a wartime season. With even a normal uptick from a return to peacetime, revenues and profits should soar.51

And in fact, that’s what occurred. Nearly all teams drew spectacularly in 1946, led by the Yankees. The club’s attendance of 2.27 million obliterated the previous major-league record, as the Yankees became the first team to draw over 2 million fans. The Yankees made $808,866 in profit that year, surely an all-time record to that point, and nearly one-third of the purchase price just one year earlier. And as with Ruppert, the Yankee triumvirate did not take any dividends — they reinvested all the profits into the ballclub.52 In 1946 the Yankees spent $583,989 on their “player replacement program,” including scout salaries, scout travel, baseball schools, newspaper and statistical services, bonuses to amateur free agents, and an allocation of the team’s general administrative costs among other items. This amount increased every year for the remainder of the decade.53

MacPhail also pushed the business potential of the club by ending the club’s radio partnership with the Giants and exploiting radio’s possibilities. The Yankees became the first major-league team to have the announcer travel with the team on the road, eliminating the campy recreations. With Mel Allen as the lead announcer both home and away, the Yankees jumped to the forefront of capitalizing on the medium. Further modernizing the organization, MacPhail introduced lights and night baseball to Yankee Stadium (as he had in Cincinnati and Brooklyn) for the 1946 season.

Webb and Topping Jettison MacPhail

After three years of running the Yankees, the pressure and constant limelight began to unhinge MacPhail. Near the end of the 1947 season he arranged an initial public stock offering of shares of the Yankees franchise through a New York investment bank. MacPhail and the bankers worked out an IPO that would make just under 50 percent of the club available to the public. The bankers estimated that this stock offering would raise about $3 million, implying a franchise value of roughly $6 million. MacPhail contrived the transaction to cash out part of his investment. Topping and Webb, however, had no desire to come under the scrutiny and reporting requirements of the public market. The two quickly resolved to buy out their partner. Just before the start of the World Series, Topping and Webb reached an agreement to acquire MacPhail’s one-third interest for around $2 million, a huge profit over his initial investment, most of which he had borrowed. Despite selling his ownership interest, MacPhail would remain as president and de-facto general manager.

The agreement to sell did not calm MacPhail. Just the opposite: His decision to surrender his ownership in baseball’s most popular franchise further troubled him. Rumors persisted that MacPhail feuded with other members of the Yankees executive team, most of whom had been in place for many years and were protégés of Ruppert and Barrow. MacPhail’s maniacal behavior culminated with his breakdown at the Yankees victory celebration dinner in the Biltmore hotel after they won the 1941 World Series. He stumbled around the dining room, alternating between bouts of sentimental crying and irrational raging. He saved his most vile epitaphs and anger to denigrate Brooklyn’s Branch Rickey, whose club the Yankees had just defeated. When John McDonald, MacPhail’s former employee in Brooklyn (against whom MacPhail still harbored a grudge for a magazine story), defended Rickey, MacPhail punched him in the eye.

MacPhail next lurched over to George Weiss’s table and berated his work. The rest of table watched in horror as MacPhail told Weiss he had “48 hours to make up your mind what you are going to do.” Weiss remained as calm as possible and suggested: “Larry, I don’t want to make a decision here tonight. We have all been drinking. I would like to wait until tomorrow and discuss this with you.” MacPhail, in no condition to be mollified, responded by firing Weiss on the spot. As MacPhail walked away, Weiss’s wife chased after him to appeal for her husband’s job, but he just ignored her. A shaken Weiss went outside to cool down and commiserate with top scout Paul Krichell. Weiss’s wife returned to the table in tears.

Topping finally seized control of the situation. He tried to calm MacPhail down only to be told he had “been born with a silver spoon in [his] mouth.” Topping then guided the still crazed MacPhail into the kitchen where the two huddled alone. After calming him down somewhat, Topping ushered MacPhail out a side door so he could gather himself. Topping and Webb accompanied Weiss up to his hotel room to reassure him of his position with the Yankees. MacPhail actually returned later, still combative, but no longer unglued. Webb and Topping, naturally, had no intention of leaving their $6 million operation in MacPhail’s hands and quickly worked to quietly terminate his Yankee contract. To run the club the duo promoted Weiss to general manager, Topping assumed the presidency, and Webb a key role on the ownership councils.

Dan Topping enjoyed a “sportsman” lifestyle that we seldom see any more in America, one founded on inherited wealth, some athletic ability, and active involvement in professional or other sports. Topping’s life also often entailed a playboy youth and multiple attractive socialite wives. His maternal grandfather amassed a fortune in the tin-plate business, started the American Can Company and had interests in railroads, tobacco, and banks. He left virtually his entire fortune of $40 million to $50 million to Dan’s mother. His paternal grandfather was a longtime president of the Republic Iron and Steel Company.

His parents gave him the education befitting a young aristocrat. He attended the Hun School, an expensive boarding school in New Jersey, where he starred in football, baseball, and hockey. He attended the University of Pennsylvania and played both baseball and football. Topping took up golf and became a top-notch amateur, winning several tournaments. After finishing school, Topping spent three years working at a bank, but quickly realized that the life of toiling for a dollar wasn’t for him.

In 1934 the 22-year-old Topping purchased a partial interest in the Brooklyn Dodgers of the fledgling National Football League. He soon acquired a majority ownership and spent some money to improve his club. By 1940 he had assembled a decent squad, but with the coming of World War II, most of the Dodgers’ best players entered the military and the team fell back in the standings.

Del Webb had survived a near-fatal bout of typhoid fever in his late 20s to build one of the West’s great construction and homebuilding empires. After he finally recovered ing from his illness, his doctor advised Webb to move to a dry climate. Webb and his wife took their $100 in savings and moved to Phoenix, Arizona. In Phoenix he began building grocery stores and when the Depression came, he managed to secure large government projects to keep his company afloat and even thrive. Webb’s contacts eventually included President Franklin Roosevelt, oil millionaire Ed Pauley, and Democratic power broker Robert Hannegan. The government contracts Webb landed during World War II made his company one of the country’s largest contractors.

Webb and Topping owned the Yankees equally. Both were wealthy and independent and neither liked or had experience with equal partners. Moreover their personalities and backgrounds were diametrically opposed: “Webb is the Far Westerner who looks as though he just shucked off his cowboy stuff,” wrote Harold Rosenthal. “Topping is an Easterner in the yachts-polo-anyone-for-tennis mold. Unless Webb has known you a long time, you’ll get a ‘yes,’ ‘no’ or ‘maybe’ from him. Topping is the open, friendly type, the kind the headmaster tells you your boy will turn out to be when you enroll him in one of the more fashionable Eastern prep schools.”54 Nevertheless, the duo made a surprisingly long-lasting and effective team.

The Yankees owners’ next high-profile baseball involvement came in December 1950 when baseball’s owners were considering extending the contract of Commissioner Happy Chandler. Webb detested Chandler and considered him rather a prude and prone to offer opinions and decisions without all the facts. Webb also had a more personal reason to dislike the commissioner. “His construction company built the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas and I investigated to make sure that Webb’s involvement with the gambling center ended there,” Chandler recalled. “This seemed a sensible and understandable precaution, but Webb was furious.”55

Webb and Topping proved adept at working the backrooms of baseball ownership. Despite initial support for Chandler among many of the owners, the Yankees duo, supported by St. Louis Cardinals owner Fred Saigh, maneuvered the vote away from Chandler. Webb was not reticent about his involvement: “If I’ve never done anything else for baseball, I did it when I got rid of Chandler.”56

In late 1953 Webb and Topping sold the franchise’s real estate, including Yankee Stadium and the minor-league Kansas City Blues stadium, to Chicago-based businessman Arnold Johnson for $6.5 million, a tidy profit considering that their total investment in the team was roughly $4.225 million after their buyout of MacPhail. The Yankees signed a 28-year lease with Johnson with rents starting at $600,000 a year and declining to $350,000 a year by the last year of the lease. As part of the deal and to help Johnson finance the transaction, Webb and Topping took back a second mortgage on Yankee stadium for $2.9 million. Johnson then flipped Yankee Stadium to the Knights of Columbus for $2.5 million, leasing the stadium back from them for 28 years at rates significantly less than what he was leasing it to the Yankees for.57

The next year, helped by some behind-the-scenes politicking by Webb and Topping, Johnson bought the Philadelphia Athletics and moved them to Kansas City. Several AL owners expressed objections to his financial relationship with the Yankees — both the sandwich lease, making him effectively the Yankees’ landlord, and the second mortgage between the owners. At the time of Johnson’s purchase, he was given 90 days to work these issues out, a time period that was eventually indefinitely extended.58

During the 1950s baseball’s owners spent considerable time and energy mulling over the geographic future of their sport. After 50 years of franchise stability, many began to salivate over the potential huge payday in untapped metropolitan areas. Webb believed in realignment as opposed to expansion, as there were still plenty of struggling two-team cities that could no longer support two teams.

By the end of the 1950s it was clear to most observers there were more major-league-ready cities than there were franchises to go around. Business interests and politicians in those cities were pressing baseball for expansion. The inherently conservative baseball owners, however, continued to resist growing beyond 16 franchises. Ironically, the greatest pressure came in New York. To rectify having only one team after the departure of the Giants and Dodgers, well-connected New York lawyer Bill Shea, with the support of New York politicians and the possibility of a new stadium in Queens, began canvassing the country for potential investors and cities in a new, third major league, dubbed the Continental League.

After fighting a cagey rear-guard action for a roughly a year, Webb eventually realized he had little choice but to accept a National League expansion team in Queens as the least bad option. He was also the driving force in directing American League expansion into Los Angeles. Although other cites appeared to have more support, Webb wanted an American League team in California, and if the National League was going to force a second team on his city, he could do the same in Los Angeles.

On the field the team dominated in the 1950s like no other team in the history of the sport. But in the aftermath of the seven-game loss to the underdog Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1960 World Series, Topping and Webb eased both manager Casey Stengel and Weiss out of their positions. “A contract with Casey didn’t mean anything,” Topping complained. “Casey was always talking about quitting. For a couple of months there [late in the 1958 season] we didn’t know whether we had a manager or not. We decided right then that we would never be put in that position again.”59 Topping also wanted to get more directly involved in the operation of the franchise, something that would have been much trickier with the imperial Weiss still in charge.

Topping quickly took to his activist role. When the Yankees won the World Series in 1961 after a two-year drought, The Sporting News named Topping its Executive of the Year for making “a radical change in the leadership of the Yankee club.” The Sporting News further touted his “courage,” and emphasized that he had become the key man running the franchise. “Had this bold move failed,” opined the paper, “Topping’s own position could conceivably have become untenable.”60

CBS Gets a Baseball Team

In August 1964 the Yankees announced the sale of the franchise to CBS, which dragged on throughout the offseason, troubled by additional revelations and commentary. Webb and Topping had first seriously considered selling the team a couple of years earlier when Topping went through some health problems. Topping felt he could no longer run the team and sounded out Webb about buying him out. Topping eventually rebounded but needed the money a sale could bring, and the two owners agreed to explore selling the team. With his many ex-wives and children to support, the proceeds from the sale of the team would ease Topping’s financial burdens.

The two initially reached an agreement with Lehman Brothers, then a large investment house. The sale was dependent on some complex tax angles, and while the lawyers and accountants were working them out, CBS chairman William Paley called his friend Topping to see if the team was available. Topping told him they were already committed in another direction, but that if something changed, he would get back to him. When the sale fell through, Topping called Paley on July 1, 1964, to see if he was still interested. Paley was, and the two began negotiations.

On August 14 Topping and Webb agreed to the final deal, selling 80 percent of the Yankees to CBS for $11.2 million. Additionally, Topping would stay on as the operating partner. Topping later testified that he had received offers as high as $16 million, “but they wanted to run the whole show, and I preferred a deal where I could remain active.”61

It is hard to overestimate the outcry generated by the sale of the Yankees to a television network. Up to this point baseball teams rarely had true corporate ownership. More importantly, in 1964 television was rightly seen as a large and growing phenomenon in American life, and its ultimate impact was not yet fully understood. The sale of America’s number-one baseball team to its number-one television network appeared to foreshadow grave consequences.

Many criticized the process as much as the substance. Fearing just this sort of reaction, Webb and Topping persuaded American League President Joe Cronin to get league approval by telephoning the league owners rather than calling a meeting. The owners approved the sale 8 to 2, but the two dissidents, Charles Finley of the Kansas City Athletics and Arthur Allyn of the Chicago White Sox, went public with their opposition. Eventually Cronin felt compelled to call a league meeting to confirm the sale, but the vote remained the same, and the sale was finalized on November 2, 1964. Webb had little desire to remain in a ceremonial position; in March he sold his remaining share for $1.4 million. Topping stayed on as team president.

Topping was soon overmatched without a strong baseball executive as general manager. After a slow start in 1966, with encouragement from CBS, Topping shook up his staff. But the team just wasn’t good enough and finished last. Topping resigned on September 19, selling his remaining 10 percent share to CBS. Topping publicly stated that he had resigned for personal reasons, but there can be little doubt that CBS wanted little to do with the men who had sold them a now struggling club for a record price. To replace Topping, CBS appointed Mike Burke, who had been an executive at CBS for several years and on the Yankees board for the past two.

Not surprisingly, a large conglomerate like CBS, with vast business holdings in a variety of industries, turned to a versatile business executive like Burke to run the Yankees. Burke, who wore tailored suits made in Rome, was a dashing figure, especially compared with the staid and conservative Yankees. He had been a football star at Penn, a war hero, a drinking buddy of Ernest Hemingway, an OSS agent, and an executive with Ringling Brothers circus, before joining CBS. His job now was to restore a legendary baseball team to its proper place of glory. “I won’t be satisfied,” he said, “until the Yankees are once again the champions of the world.”62

Once in charge, Burke and general manager Lee MacPhail (Larry’s son) smartly rebuilt the organization’s talent level. Nevertheless, despite several years of slowly improving talent, CBS decided to sell. Having purchased the most famous franchise in sports just eight years earlier, CBS was reportedly losing money on the Yankees, though that was not the primary motivation for selling. CBS had bought the team for its famous brand, in order to bring additional prestige to its hugely successful media company. Instead, the team fell from glory and many fans tended to blame the largely unseen corporate managers for the change in fortune. “CBS came to the conclusion,” said a spokesman, “that perhaps it was not as viable for the network to own the Yankees as for some people. Fans get worked up over great men, not great corporations. We came to the realization, I think, that sports franchises really flourish better with people owning them.”63

George Steinbrenner Takes Center Stage

In mid-1972 CBS chairman William S. Paley asked Burke to put together a group to buy the club, and Burke looked for a purchaser that would allow him to continue running the team. Cleveland Indians general manager Gabe Paul introduced Burke to George M. Steinbrenner, the 42-year-old CEO of American Shipbuilding Company who had recently come very close to purchasing his hometown Indians. A decade earlier Steinbrenner had taken over the small Great Lakes shipping company from his father, bought out most of his competitors, and built an empire.

In mid-1972 CBS chairman William S. Paley asked Burke to put together a group to buy the club, and Burke looked for a purchaser that would allow him to continue running the team. Cleveland Indians general manager Gabe Paul introduced Burke to George M. Steinbrenner, the 42-year-old CEO of American Shipbuilding Company who had recently come very close to purchasing his hometown Indians. A decade earlier Steinbrenner had taken over the small Great Lakes shipping company from his father, bought out most of his competitors, and built an empire.

Although hardly a household name, Steinbrenner had been involved with sports teams for many years. Once a track star at Williams College, he was later a football graduate assistant to coach Woody Hayes at Ohio State and had held football coaching positions at Northwestern and Purdue. In the early 1960s he bought the Cleveland Pipers, a team in the short-lived American Basketball League, and made an immediate splash by signing the most coveted college player in the country, Ohio State’s Jerry Lucas. The league soon folded, but a few years later Steinbrenner bought a stake in the Chicago Bulls and began acquiring racehorses.