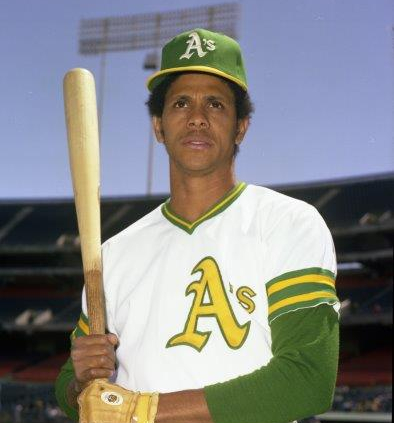

Miguel Diloné

A right-handed-throwing, switch-hitting outfielder who had much more success from the left side because of his ability to “swing-and-run” and beat out slap base hits, Miguel Diloné was perhaps the quintessential journeyman. He played for seven teams (including two stints with the Pirates) over a 12-year career and had more than 400 plate appearances in only two of those years. While his career numbers, including a slash line of (.265/.315/.333) in 2,182 plate appearances during those 12 years would not stand out to anyone, there was one glorious summer when Diloné was third in batting average in the American League.

From the moment Diloné hit a baseball field in the United States, he was off and running. Born on November 1, 1954, in Santiago, Dominican Republic, he was signed as a 17-year-old by the Pittsburgh Pirates. In that 1972 season, Diloné came in third in stolen bases in the New York-Penn League as an outfielder for Niagara Falls. He stole 41 bases in 61 gamesd and was caught only 10 times. In 1973, Diloné was promoted to the Class-A Western Carolinas League and proceeded to set a league record with 95 stolen bases in 115 games. As a 19-year-old playing for Salem in the Carolina League, Diloné was having his best year yet in 1974. He was batting .333/.414/.444 with 85 stolen bases when he was called up to Pittsburgh for September. He was the youngest player in the National League at the time.

In the second game of a home doubleheader against the Philadelphia Phillies on September 2, 1974, Diloné came in to play center field in the ninth inning as part of a double-switch in an 11-1 Pirates victory. No plays were needed in center field that day. Diloné’s first plate appearance came a few days later, on September 7 against the Montreal Expos. It was the bottom of the 12th inning in a 5-5 game with a runner on first base and two outs when manager Danny Murtaugh called on Diloné to hit for pitcher Ramon Hernandez. He worked a walk from pitcher Dale Murray. The Pirates’ young slugger Dave Parker followed Diloné to the plate and drove in the winning run.

Throughout the rest of that season, Diloné continued to see time as a pinch-hitter and primarily as a pinch-runner. He got his first major-league stolen base on September 15 at Montreal. He scored his first run on September 23, in the top of the 10th inning of a 5-4 Pirates victory. Diloné’s first run at the major leagues in 1974 ended with 12 games but only three plate appearances. He walked once and stole two bases, scoring three times and still looking for his first hit.

For his 20-year-old season in 1975, Diloné largely repeated 1974. He spent the bulk of the year in the minors again, but this time in Triple A at Charleston in the International League. He struggled much more at the plate, posting a slash line of .217/.291/.270 in 125 games. He was still a speedster but was kept to 48 stolen bases at this level. Once again he was a September call-up and saw time primarily as a pinch-runner. He got into 18 games, with six plate appearances. He scored eight runs and added two stolen bases, but still had no major-league hits. The 1976 season was a near-repeat performance statistically with the bulk of the year spent at Triple A (though he did manage a .336 batting average in 449 plate appearances) and a September call-up.

Diloné got his first starting assignment on September 28 against the Cubs. Starting in center field and leading off, he was 2-for-4. Diloné wasted no time, beating out a groundball to third base. He scored on a sacrifice fly by Richie Zisk. With his first two singles (he also beat out a groundball in the hole to shortstop in the third inning), Diloné showed off the “slap-and-run” style that characterized his hitting at its best. With 1977 a near repeat of the previous three years (substitute Columbus for Charleston as Pittsburgh moved their Triple-A affiliates and add an extended stay on the disabled list for a dislocated finger from a stolen-base attempt), Diloné spent the Septembers of four consecutive seasons with the Pirates. His cumulative line for his efforts was .145/.181/.145 in 75 plate appearances, with 21 stolen bases and 23 runs scored. The speed was real, but the Pirates felt they had seen enough.

On April 4, the eve of the 1978 season, the Pirates traded Diloné along with Elias Sosa and a player to be named later (Mike Edwards) to the Oakland Athletics. The A’s sent the Pirates former Pittsburgh legend Manny Sanguillen so that he could finish his career as a Pirate after a brief sojourn in Oakland. Diloné spent only one year with Oakland, but the A’s did give him the chance to spend the whole year in the major leagues, installing him as their regular left fielder. He stole 50 bases but still strugglde mightily at the plate. He hit .229/.294/.271 though he was able to get his first major-league home run.1 In 1979 Diloné started out with Oakland but his struggles continued. He was batting .187/.237/.275 when he was sent down to Triple-A Ogden on June 24. Diloné was rescued from more time at Triple A when the Chicago Cubs purchased his contract from the A’s on July 4. Used again primarily as a pinch-runner and defensive replacement with a few spot starts, he batted .306/.342/.306 with 15 stolen bases in 38 plate appearances.

The 1980 season began, as so many previous years had, with Diloné not making the team out of spring training and being sent to the minor leagues, Wichita of the American Association in this case. He did not spend much time in Wichita, however, as the Cleveland Indians came calling and purchased his contract from the Cubs on May 7. He got a chance to play regularly in Cleveland in 1980 and made the most of it. Originally brought in as an injury replacement for center fielder Rick Manning, Diloné platooned in left field briefly with Joe Charboneau but quickly earned the starting job. He was frustrated with his reputation as a speedster who couldn’t hit and felt it was due to his lack of consistent playing time. In an interview with the Akron Beacon Journal in August of 1980, he said, “People said I can’t hit. They see my .214 batting average [his career mark heading into 1980]. But I never played regular. I only played eight games in a row once until this season.”2 Missing 25 games that season before the Indians acquired him, Diloné blew away his career marks with a line of .341/.375/.432 and added a team-record 61 stolen bases (third in the American League). His .341 mark was also third in the league – well behind AL leader George Brett’s .390 but still very impressive.

It looked as though Diloné had perhaps finally found his spot. Maybe he was right and all it took was regular playing time for him to prove himself. He looked forward to the 1981 season as an opportunity to prove that 1980 was no fluke. During the 1980-1981 offseason, he did as he always did and returned to his native Dominican Republic to spend time with family and play more baseball. He was three days late in reporting to Arizona for his first spring training with the Indians because of some legal trouble back home. Diloné had been accused of statutory rape after a consensual sexual encounter with a young woman who said she was 17 years old. The case was adjudicated in the Dominican court system and it was determined that the young woman, at the urging of an unscrupulous attorney, had falsified her birth certificate (she was actually 18) in an attempt to extort $5,000 from Diloné. The court proceedings obviously distracted Diloné and caused him to be late for spring training.3

When he was finally able to report to camp, Diloné was surprised (and offended) to learn that his starting job was in jeopardy even after his breakout performance in 1980. “From the day I came to camp,” he said in broken English, “I was confused. First I couldn’t get out of the [Dominican Republic] because I was accused of rape. Then I arrive late and I am told I have to fight for my job in left field. Why should I have to fight for a position after I bat .341 the season before? I don’t understand that.”4 Diloné did not respond well to the challenge, as he acknowledged a year later – “Now I am prepared to fight [for my starting job]. Last spring I was not.”5 That strike-shortened 1981 season was a part-time season for Diloné and his numbers took a step back. In just 72 games and 289 plate appearances, he hit .290/.334/.346. His speed was still there, as he stole 29 bases in this limited time. Diloné beat out Charboneau for the starting job in 1982 and things looked hopeful for him – he was given regular playing time again. But he did not perform. His game slipped quickly. In 412 plate appearances (the second-most of his career, to 1980) he hit only .235 and stole only 33 bases, a rate far lower than he had previously been hitting.

Things went from bad to worse quickly in 1983. At age 28, Diloné should have been entering his prime, but the numbers did not bear that out. Through July 14, when the Indians demoted him to Triple-A Charleston, Diloné was batting only .191. Worse from a media perspective is that Diloné was being paid $225,000 to hit in Triple A, making him the most expensive minor leaguer the Indians had ever had. Cleveland’s coaches thought the problem was one of approach – they believed that Diloné had stopped bunting for hits and was trying to hit for power, and it ruined his value. General manager Phil Seghi said, “He started swinging for the fence. Everything he hit was in the air. He quit bunting. Then the bottom fell out of his batting average.”6 So the Indians sent Diloné to Triple A hoping he could return to his old form. It would not happen again in Cleveland. On September 1 Diloné was traded as the player to be named later in an earlier deal in which the Indians received Rich Barnes from the Chicago White Sox. He played in only four games for the White Sox, going 0-for-3 with one stolen base and one run scored. Less than a week later, on September 7, Diloné was traded back to Pittsburgh along with minor leaguer Mike Maitland for Randy Niemann. Back with the Pirates, Diloné repeated his early-season pattern in Pittsburgh, appearing seven times but only as a pinch-runner.

A free agent for the second time, Diloné was signed this time by the Montreal Expos in January 1984 to a one-year deal. He played most of two seasons for the Expos as a 29- to 30-year-old. For a player whose game depended on speed, the decline came quickly. In shared playing time in 1984 and 1985 with Montreal, he had 280 plate appearances and hit .249/.312/.324 with 34 steals. The stolen-base numbers were starting to slip as well. On July 10, 1985, Diloné was released by the Expos. He signed as a free agent with the San Diego Padres two weeks later. After spending two weeks in Triple-A Las Vegas, Diloné joined the Padres. He ended his career as it always had been – not hitting much and for very little power but running when he was on base. His San Diego line in 27 games and 50 plate appearances, was 10 stolen bases and .217/.280/.261. That was the end of major-league baseball for Miguel Angel Diloné.

From the Dominican Republic to Pittsburgh to Oakland, Chicago (Cubs), Cleveland, back to Chicago (White Sox this time), back to Pittsburgh, to Montreal and San Diego over the course of 12 years, Diloné slapped and bunted his way on base and ran with the best of them. His career averages of .265/.315/.333 show a hitter whose batting average was close to average, but who hit for almost no power. His 267 stolen bases place him 207th all-time, but his rate was a bit better. He was more successful than his peers, so his career success rate of 77.39 percent bumps him up to 58th place.

During and after his major-league career, Diloné played in his native Dominican Republic for 22 seasons. He led the Dominican League in stolen bases for 10 of his first 12 years and as ofg 2019 still held the league’s career stolen-base record.

In a freak accident on a foul tip during a practice, Diloné was struck in the face by a baseball and lost his left eye in 2009. He was coaching a 15-year-old prospect and giving him batting tips at the time.7 As of 2019 he remained active in baseball in his hometown of Santiago and throughout the Dominican Republic.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.com

Notes

1 This was a rare occurrence indeed, as he ended his career with only six home runs. This one came to lead off the bottom of the first inning for the A’s against the Yankees’ Don Gullett in a 6-4 A’s victory.

2 Bob Nold, “There’s No Doubt About His Speed …,” Akron Beacon Journal, August 5, 1980: B1.

3 Sheldon Ocker, “Acceptable Excuses: Jail or Death,” Akron Beacon Journal, March 5, 1981: B1.

4 Hal Lebowitz, “The Other Face of Senor Dilone,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 22, 1982: 1-C.

5 Lebowitz.

6 Terry Pluto, “Dilone’s Demise Is Hard to Figure Out,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 16, 1983: 6-C.

7 “Miguel Diloné Loses an Eye in Baseball Accident,” Diario Libre, March 17, 2009. Retrieved from web September 30, 2018.

Full Name

Miguel Angel Dilone Reyes

Born

November 1, 1954 at Santiago, Santiago (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.