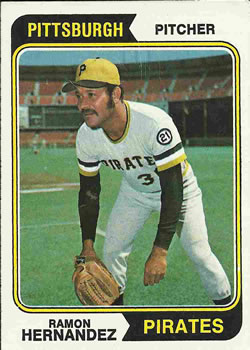

Ramón Hernández

Ramón Hernández pitched in 337 big league contests, but he was born in the wrong age. His relatively short nine-season career in the majors (1967-68; 1971-1977) could have been extended had he started playing in the 1990s, when specialized bullpen roles had become more commonplace. Modern strategists would have likely found a way to maximize usage of the Puerto Rican’s key attribute: his deceptive left-handed delivery.

Ramón Hernández pitched in 337 big league contests, but he was born in the wrong age. His relatively short nine-season career in the majors (1967-68; 1971-1977) could have been extended had he started playing in the 1990s, when specialized bullpen roles had become more commonplace. Modern strategists would have likely found a way to maximize usage of the Puerto Rican’s key attribute: his deceptive left-handed delivery.

Had the situation been different, Hernández might have enjoyed a career like those of Mike Stanton, Tony Fossas, or Jesse Orosco, who thrived by retiring left-handed batters with ease, often neutralizing their opponents with movement and guile rather than triple-digit heat. But the lefty-one-out-guy, or LOOGY – a hallmark of modern baseball – was not yet in vogue.

Hernández was also hindered in his younger years by conflicts with management. As his teammate in Puerto Rico, Benny Ayala, said, “He could have done more in the majors. He did his own thing. The coaching staff did not attempt to enforce the rules with him. We knew he had his quirks – he was controversial at times and would often disappear into the clubhouse. You had to dance to his beat.”1

More than a decade after making his professional debut, Hernández blossomed in the early 1970s with the Pittsburgh Pirates, an ethnically and culturally diverse squad where he fit in well. Diminishing effectiveness kept Hernández from pitching in the majors past age 37, and Ayala noted another contributing factor. As the years caught up with Hernández, “he would hate to see the batter square up to bunt as he knew he’d have to field the ball.”2

Ramón Hernández González was born on August 31, 1940, in Carolina, Puerto Rico, a suburb of San Juan. By the late 1950s, the city had produced only one major leaguer: the island’s all-time great, Roberto Clemente. Information regarding Hernández’s family background and youth has not yet surfaced. As an adult, he grew to 5-feet-11 and 160 pounds, not very imposing for a pitcher, but his skills enabled him to debut in Puerto Rico’s professional league a few months after his 18th birthday. He went on to play winter ball there for a remarkable 21 seasons, donning the uniform of every one of the league’s franchises.

Nicknamed “Mon” (short for his given name), Hernández was inked by Pittsburgh as an undrafted free agent in 1959, thanks to the keen eyes of Howie Haak. The Pirates assigned him to Grand Forks of the Class C Northern League, where he walked 63 hitters, almost as many as the 69 he struck out in 71 innings. The combination yielded a 7.73 ERA, a tough welcome for a teenager playing against competition almost three and a half years older than him on average.

In 1960, Hernández cut his ERA by more than half – albeit in just 11 games between Grand Forks and Dubuque of the Class D Midwest League. His season was cut short by both injury and suspension (although press coverage does not shed any further light on these issues). Upset about his demotion, Hernández sat out the 1961 season. “I went home,” he recounted in 1972. “I worked at a lot of different jobs.”3 The Pirates sold his contract to the Los Angeles Angels on December 4, 1961. Starting afresh with a new franchise, he saw extensive action for its San Jose affiliate in the Class C California League, logging 138 innings as both a starter and reliever in 1962. He punched out almost twice as many batters as he walked and kept the ball in the stadium (only two home runs) to win seven games against six defeats. He posted a sharp 2.93 ERA. Although things were looking up, Hernández’s temper generated another suspension (alas, further detail is lacking here too). As a result, he spent the 1963 season largely in the wilderness. He appeared in seven games for Reynosa of the Mexican League and just five others for the PCL’s Hawaii Islanders.

Hernández returned to San Jose in 1964, splitting a dozen decisions while struggling with his control (70 walks, 85 strikeouts) in 94 innings. Nonetheless, before the 1965 season, the Angels promoted him to El Paso of the Double-A Texas League. He pitched in a total of 95 games in 1965 and 1966, striking out 199 opponents and earning a short, six-game opportunity with Seattle of the PCL, during which he went 0-2 with a 5.25 ERA, striking out eight batters in 12 innings. Given his minor league tenure, he was eligible for the Rule 5 draft of players not on the 40-man roster, and Atlanta selected him on November 28, 1966.

At a still-young 26 years, Hernández broke camp with the Braves for the 1967 season and was pressed into immediate duty, tossing 1 2/3 innings in the April 11 season opener against Houston. He entered the game in the seventh frame – the fourth Atlanta pitcher of the night – and allowed two runners (one inherited) to score. He returned in the eighth, allowing one hit, but finished the game with three strikeouts, including future Hall of Famer Eddie Mathews. In his next outing, on April 15, he retired both hitters he faced to earn his first major league save, and ended the season with five saves and two losses for the 77-85 Braves.

The club did not protect him on its 40-man roster, allowing the Chicago Cubs to claim him on November 28, again via the Rule 5 draft. Before spring training, pitching coach Joe Becker stated, “I just hope he’s as good as they say he is because we need a consistent lefty for emergency calls. The day in baseball is gone when you expect a starter to finish.”4 Becker was ahead of his time, pinpointing Hernández’s critical value for any big league club, even though the LOOGY revolution would not start in earnest for two more decades. As analyst Steve Treder pointed out, despite various examples in the mid- to late 1960s and early ’70s, “Across the decade of the 1970s and beyond, the LOOGY went into a long period of near-hiatus.”5 By the 1990s, more than 40 hurlers fit that category, but back in the 1970s, most relievers took the mound regardless of the batter’s location in the box. Starters often went deep in the game, so relievers were expected to enter a game regardless of the scenario, not to be used when a specific setting arose.

Hernández’s 1968 big league action did not last long. He appeared in eight games for the Cubs but was hit hard, allowing nine runs in as many innings. St. Louis purchased his contract on June 14, but he would not wear the Cardinal uniform in the big leagues. His misfortunes continued with Tulsa of the Triple-A PCL, playing in 18 games and posting a 6.19 ERA while clashing with manager Warren Spahn, as he would admit a few years later.6 Yet Hernández’s peripheral statistics – two home runs allowed, eight walks, and 31 strikeouts in 32 innings – were good. That prompted the organization to give him another chance in 1969 with Double-A Arkansas of the Texas League. Hernández swung between the starting rotation and the bullpen, compiling a solid 10-10 record with a 2.40 ERA in 184 innings. He struck out 133 against just 38 walks. The season’s highlight was a one-hour, 17-minute no-hitter on August 17. Manager Ray Hathaway was quite pleased, commenting, “What else could you call it but a masterpiece? The guy works fast, has great control, and when he really has it, like he did today, he makes this a simple business.”7

Although Hernández’s performance on the mound was robust, his demeanor worried both the club and the league. A salient example came on May 25, 1969: Hernández slid into third base, got entangled in a fight, and swung the base against the fielder. It encapsulated the quandary: a talented pitcher who would often lose his cool.8 The Cardinals released him on March 31, 1970. That might have been the end of the road, but Hernández headed south. He joined the Mexico City Reds of the Triple-A Mexican (Summer) League and pitched admirably: 5-3 with a 1.82 ERA in 79 innings, including 56 strikeouts against nine walks. The Pirates reacquired Hernández on February 10, 1971, in exchange for Danilo Rivas, another left-handed pitcher. José Pagán played with him in the Puerto Rican Winter League and was puzzled why no team had inquired about him. His scouting report found its way to Pittsburgh, which re-signed Hernandez more than a decade after Haak had first inked the lefty.

Hernández was assigned to Triple-A Charleston, where he pitched 47 innings without yielding a home run. That prompted a brief June call-up (two games) and a September promotion (eight more appearances). Against the Cardinals, who had given up on him the previous year, Hernández was outstanding: one baserunner in six innings. He carried a grudge against St. Louis general manager Bing Devine for years. “He thought I was too old,” he told The Sporting News in 1973.9 The accusation, common against Latin American players, would plague him for years. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch was more balanced, calling Hernández a “super reliever” who “this season has faced the Cardinals four times and has retired 18 men in order…Hernandez, who uses a big variety of pitches, including a screwball, also might have had revenge in mind…there were such problems as reporting late for practice sessions. Ramon was on time last night, however, much to the Cardinals’ regret.”10

According to postseason roster rules at the time, Hernández was ineligible to be on the LCS roster. This caused some frustration for the hurler that carried over into 1972. The team provided navy sports jackets to wear as a group during travel days; a “World Series Champions” insignia adorned the left breast. Hernández removed his emblem, stating he should not be able to wear it if he was not able to wear the championship ring.11 The episode reflected the ongoing chafing between a proud man and the rules that robbed him of recognition.

After a vagabond career to that point, Hernández was eager to find a permanent home. Pittsburgh, with a significant Latino presence in its clubhouse, was a great fit. Queried as to why Hernández was so at ease in Pittsburgh, general manager Joe Brown mused, “Most clubs don’t have as many Latin American ballplayers as we do. He feels at home here. He had two people in whom he has great confidence, Pagán and Clemente. He respects them and listens to them.”12

The sentiment was echoed by Puerto Rican baseball man Luis Rodriguez Mayoral, who described Hernández as “happy go-lucky, not an ounce of malice. He and Roberto were like brothers. Some of Roberto rubbed off on him; he was always sharply dressed.” However, he experienced some negative times. Few outside his inner circle realized he suffered from epilepsy; a car crash, likely the result of an episode, was immediately regarded as a drunk driving instance. Sportswriters regarded his silence as moodiness, but as Clemente explained, while Hernández was not a talker, “he knows he is welcome here. He doesn’t speak English real good, but the players on this club let him know they like him, just by an occasional smile, or maybe a jab in the ribs.”13 The press acknowledged his reticence, with occasional short commentaries: “Ramon does talk once in a while with close friends, Jose Pagan and Roberto Clemente. Most of the time he smiles an acknowledgement as a hello.”14

Hernández’s best major league performance came in 1972, when he won five games and saved 14 others (seventh-best in the National League), while allowing only three home runs all year. He co-anchored the Pirates’ bullpen with right-hander Dave Giusti, who welcomed the collaboration, citing Hernández as “the best I’ve ever seen at getting out left-handers, and I mean ever.”15 Ayala remarked, “He had a sidearm style, so it was really hard to pick up the ball and he had good control.”16 Rodriguez Mayoral agreed, stating, “Hernández was never the hardest thrower, but he was conscious of how to pitch to the batter, how to position the pitch. He could be deceptive, crafty, tricky…that allowed him to dominate. He had a rubber arm and could have pitched until age 40 in the major leagues…I do not recall him once complaining about a sore arm.”17 While discussing how middle relievers are often unsung heroes of a team, author David Finoli noted that Hernández “had an arsenal of three pitches, a screwball, a fastball, and a curve that he threw each from three different angles, overhand, sidearm, and from an angle that was almost underhand.”18 Opponents across the league noticed, with Philadelphia manager Frank Lucchesi noting that his motion had “a lot to do with it. It’s very deceptive. And he doesn’t beat himself with walks. He’s got fair stuff.”19 Hernández himself was more succinct: “I do it with a bunch of garbage.”20

The Pirates lost to Cincinnati in the LCS. However, Hernández pitched creditably, appearing in three games and allowing only one baserunner (a round-tripper to Joe Morgan in the second game). He saved the first game of the series, forming with catcher Manny Sanguillén the first Hispanic battery in postseason history.21 The 1973 season appeared promising, with Pittsburgh expected to again win its division, but tragedy struck. Clemente, the club leader and spokesperson for the Latino players, died in an airplane accident on New Year’s Eve 1972.

Hernández struck out 64 batters in 89 2/3 innings in 1973 – both career highs – while winning four games, losing five, and saving 11 others. The Pirates finished in third place behind the surprising New York Mets. While the entire team was affected by the drastic and sudden loss of its soul, Hernández was devastated. He had lost not just a teammate but also his biggest advocate.

In 1974 Hernández won five games, lost two, and saved two others. His postseason performance was flawless, tossing 4 1/3 innings in two games without yielding a run, but the Dodgers beat the Pirates in four games. In 1975 he won a career-high seven games while not allowing a single home run in 64 innings, but the Reds tagged him for two runs in two-thirds of an inning in the third and final game of the LCS, his only post-season decision. Although his numbers in the playoffs were solid (0.96 WHIP in 8 1/3 frames), Pittsburgh lost all three of those appearances. The New Pittsburgh Courier lauded his contribution to the Pirates in a rare one-page article on the quiet pitcher: “This year he is just as much a part of the Pirates’ success as anyone…part of the reason of his obscurity is that he doesn’t speak English that well and is a very quiet man…when all the cheers and congratulations are over, look somewhere in the background where Mr. Hernandez will be standing, and let’s hear one for the quiet forgotten man who does his job day in and day out superbly without any fanfare.”22

Hernández was also at his peak in Puerto Rican winter ball from 1971-1972 to 1974-1975. He posted four consecutive seasons with a sub-2.00 ERA. A high point came in the 1974 Caribbean Series as a reinforcement for Caguas.23 His two saves earned him a spot on the series’ All-Star team, alongside future Hall of Famer Gary Carter.24 Hernández’s stay in Pittsburgh ended in 1976 when the club sold his contract in early September to the Chicago Cubs, for whom he appeared just twice over the remainder of the season. His last year in the majors, 1977, proved to be disappointing. He allowed seven earned runs for the Cubs in 7 2/3 innings before being traded to the Red Sox in late May for Bobby Darwin.

Although he originally rejected reporting to Boston, he appeared in a dozen contests and posted a 5.68 ERA. His first six appearances for the Red Sox – all in June road games – ended in the team’s defeat. In his last major league appearance, on July 27, the Sox trailed Milwaukee, 7-5, in the ninth when he came in and gave up four runs. Boston released him on August 20. Hernández was then coming up on his 37th birthday – not an advanced age compared to many of the LOOGYs who would emerge in subsequent decades. In an era of expanded bullpens, it is tempting to think that he should have received at least one more chance. Back in 1977, however, 10-man staffs were still the norm. No clubs expressed interest in him, and he returned to Puerto Rico, where he lived for the rest of his life.

For his big-league career, Hernández compiled a respectable 23-15 record with 46 saves. In his 337 relief appearances, he posted a 1.241 WHIP across 430 1/3 innings. He allowed just 23 home runs, a remarkable feat regardless of the era. Using modern statistics, his value resonates further, as a 116 ERA+ and 6.2 WAR demonstrate. He ranks fifth in ERA (2.51) and third in FIP (2.90) among all-time Pirate relievers with at least 150 career innings pitched. Many Hall of Famers were befuddled by his repertoire. Among those he faced, only Johnny Bench (3-for-10, .700 slugging) and Billy Williams (5-for-15, .733 slugging) had significant success. Lefties managed an anemic .583 OPS against Hernández across 611 plate appearances (roughly a third of his major-league total). Overall, he was stronger as the season progressed, yielding a .552 OPS to hitters from either side of the plate in September and October.

Hernandez last pitched in Puerto Rico in the 1979-1980 season. He won 58 games and lost 46 with a 2.75 ERA in 370 games, second most all-time in PRWL history.25 Little is known of his post-baseball career. He owned a liquor store in Carolina and began drawing his major league pension in the late 1980s. He had heart problems later in life, likely contributing to his death on February 4, 2009, though the cause of death was not revealed. He was survived by his wife Myriam (née Ortiz) and children Vila, Ramón Jr., and Mabel. He is buried in his birthplace of Carolina.

Ramón Hernández’s feats were recognized in his homeland in 2013, when he was named among the 75 best players of the Puerto Rico Roberto Clemente Walker Baseball League, alongside his former teammates Clemente and Cepeda.26

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Benny Ayala and Luis Rodríguez Mayoral for sharing anecdotes from their careers (telephone interviews).

Thanks also to:

- Jorge Colón Delgado and Thomas Van Hyning for providing Puerto Rican Winter League statistics

- David Finoli for providing information on the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates NLCS roster

- SABR member Mark Tomasik for providing articles from The Pittsburgh Press

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

In addition to the notes referenced below, the author consulted retrosheet.org and baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Personal interview with Benny Ayala, October 25, 2020. (hereafter Ayala interview).

2 Ayala interview.

3 Bob Smizik, “Ramon Hernandez: Red-Hot Retread,” Pittsburgh Press, May 31, 1972: 69.

4 Edward Prell, “Cubs Pin Flag Bid on Pitchers,” Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1968: C3.

5 Steve Treder, “A History of the LOOGY: Part Two,” The Hardball Times, April 26, 2005, https://tht.fangraphs.com/a-history-of-the-loogy-part-two/

6 Russo, “Birds Promising—For ‘72,” St. Louis Post–Dispatch and Pittsburgh Press, Sept 17, 1971: 1B & 6B.

7 “Puente, Hernandez Hurl TL No-Hitters,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1969.

8 Jerry Wagoner, “Leg Brace No Problem for Hill Whiz Gary,” The Sporting News, June 14, 1969: 41.

9 Charley Feeney, “Silent Ramon Buc Rouser in Relief,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1973: 18.

10 “Birds Promising—For ’72.”

11 Charlie Feeney “Playing Games,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 12, 1972:13.

12 Bruce Markusen, “#Cardcorner: 1973 Topps Ramon Hernandez,” https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/card-corner/mysterious-ramon-Hernandez.

13 “Silent Ramon Buc Rouser in Relief.”

14 Al Abrams, “Sidelights on Sports,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 31, 1972:21.

15 “Pirates’ Reliever Stuns Astros,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 7, 1972: 35.

16 Ayala interview.

17 Personal interview, Luis Rodriguez Mayoral, October 23, 2020.

18 David Finoli, The Pittsburgh Pirates All-Time All-Stars: The Best Players at Each Position for the Bucs, Lyons Press, 2020, 228-229.

19 “Ramon Hernandez: Red-Hot Retread.”

20 Bill Christine, “Gypsy Ramon To Stay Put?” Pittsburgh Press, March 31, 1972: 21.

21 Lou Hernández, Chronology of Latin Americans in Baseball, 1871-2015 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2016).

22 Ulish Carter, “Hernandez the Quiet Man Who Gets the Job Done,” New Pittsburgh Courier, August 2, 1975: 21.

23 https://beisbol101.com/ramon-mon-Hernandez/

24 Thomas Van Hyning, “Caguas Criollos: Five Caribbean Series Crowns and Cooperstown Connections,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2018 (https://sabr.org/journal/article/caguas-criollos-five-caribbean-series-crowns-and-cooperstown-connections/)

25 “Líderes de Todos Los Tiempos,” Beisbol101.com (https://beisbol101.com/lideres-de-todos-los-tiempos/#tab-tb_ie72536-5)

26 Liga de Béisbol Profesional Roberto Clemente Walker, November 13, 2013 (https://ligapr.com/lbprc-escoge-a-los-75-jugadores-mas-destacados/)

Full Name

Ramón Hernández Gonzalez

Born

August 31, 1940 at Carolina, (P.R.)

Died

February 4, 2009 at Carolina, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.