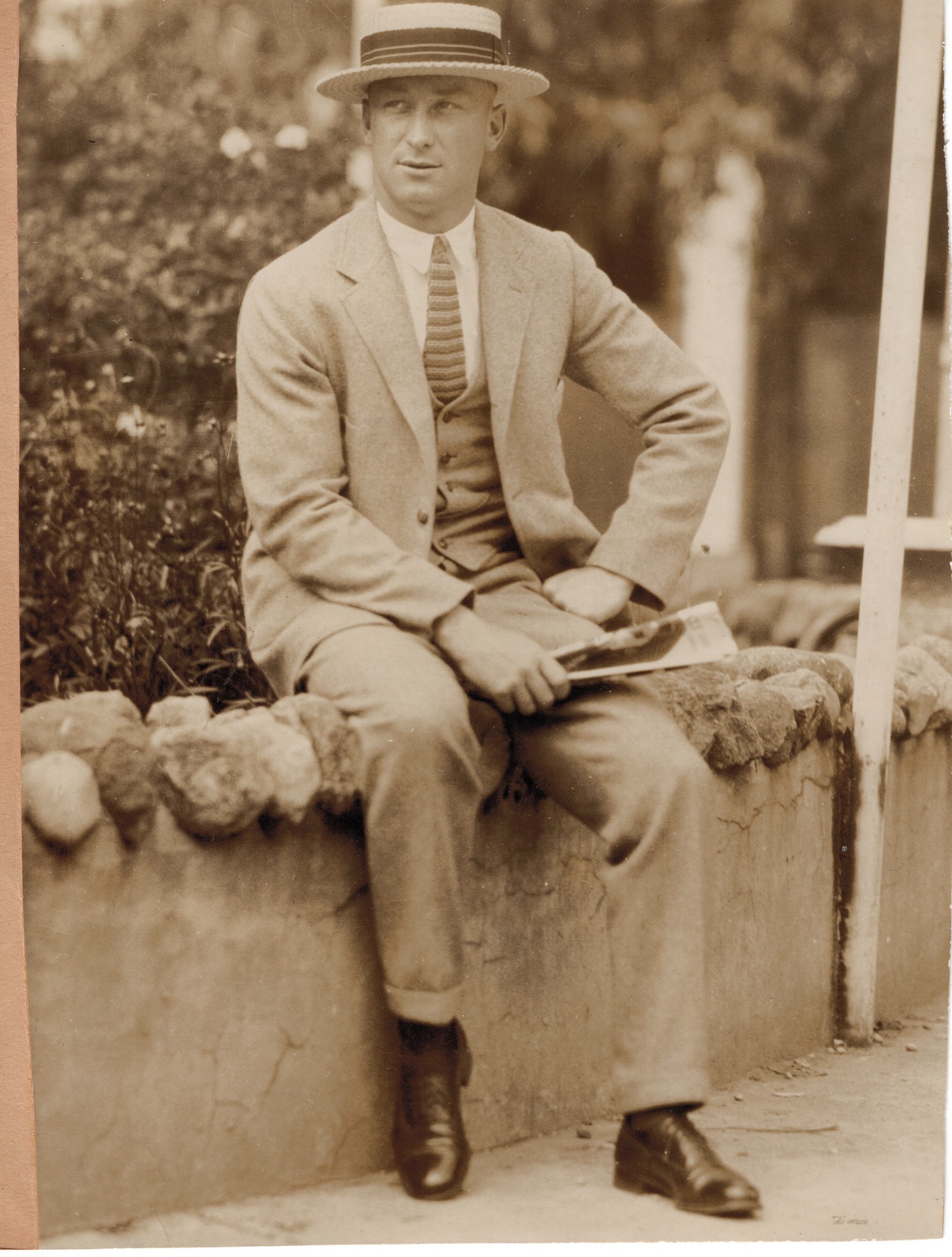

Myles Thomas

Myles Thomas was the winning pitcher in seven of the New York Yankees’ 110 victories in 1927. He also has the distinction of owning the fifth-highest batting average (.333) on a team known as Murderers’ Row.

Myles Thomas was the winning pitcher in seven of the New York Yankees’ 110 victories in 1927. He also has the distinction of owning the fifth-highest batting average (.333) on a team known as Murderers’ Row.

But there’s more. In real life, Myles Thomas was a Pennsylvania farmer’s son, a baseball star for Penn State, a Yankee whom Babe Ruth used to call “Duck Eye,” a Washington and Hartford Senator, a pitcher who baffled hitters until the age of 42, a minor-league coach and manager, a mechanic and a car salesman, a devoted husband and father, and the doting grandfather of two boys.

He also must have been a good friend.

That was apparent on the day that former Yankee pitcher Urban Shocker was buried in September of 1928. There were more than 1,000 mourners in attendance at All Saints Church in St. Louis. Shocker, who had won 18 games for the ’27 Yankees, died of heart failure in Denver on September 9, but because the team was coming to his hometown to play the Browns, services were delayed a few days.

The attendees saw six men carrying his casket: Hall of Famers Lou Gehrig, Waite Hoyt, and Earle Combs; Gene Robertson, an old Browns teammate; Yankee utility infielder Mike Gazella, and, yes, Myles Thomas.

Shocker had literally died to win those 18 games. Suffering from congestive heart disease, he would sleep sitting up because he might start choking if he lay down. Because he wanted to keep pitching, only a few people knew the seriousness of his condition. One of them had to have been Thomas, who was one of Shocker’s roommates on the road.

No, Myles did not keep a diary. But it would have made for good reading. He knew famous people, and he knew them well. His baseball coach at Penn State was Hugo Bezdek, the only man ever to manage a major-league team and coach an NFL team. His Penn State teammate Hinkey Haines won both a World Series and an NFL title. He played with Hall of Famers on the Yankees and Washington Senators. He was good friends with Fred Haney, the man who managed the Milwaukee Braves to a World Series title in 1957, when they beat the Yankees. Thomas helped get Fred Hutchinson to the majors, and then saw his former pupil nurture the careers of Frank Robinson and Pete Rose. His daughter Myrtice dated legendary golfer Frankie Stranahan and married Carl Happer, a baseball and football star at Auburn.

In other words, Myles Thomas had a front row seat to American sports in the 20th century.

He died of a myocardial infarction on December 12, 1963 at the age of 66. Two of his descendants, grandsons Tom and Joe Happer, knew a little about his days with the Yankees, but a great deal more about his nature.

“Pappy was just a sweet man,” Tom later recalled. “One time, he was giving me my bath — I must’ve been about 5. Well, he accidentally got some soap in my eye. I started crying and crying, even after he wiped it away. Do you know what he did? He went and put some soap in his own eyes, looked at me and said, ‘See, it’s not so bad.’ And I stopped crying.

“Here’s the best part of the story. After that, I would wander into his bathroom to see him shave. And I would say, ‘Pappy, put some soap in your eyes.’ And he would, even though I could tell it was stinging his eyes.”

Joe recalled, “He rarely talked about his time with the Yankees. But he was still a hero to us.”

Myles Lewis Thomas was born on October 22, 1897 in State College, Pennsylvania. His mother, the former Sallie P. Bowman, and his father, Dicen Blanchard Thomas, lived on a farm in Bellefonte, 12 miles east of State College. They had four children in this order: Wynona, Ralph, Myles and Kenneth.

With only census records as a guide, and without a formal family history, it’s difficult to retrace the path Myles took from childhood to his enrollment at nearby Penn State. But he did register for the draft in September of 1918 — he was described as tall and slender with blue eyes and brown hair — and his listed occupation was farm laborer.

Centre County was renowned for both its agriculture and baseball products. Bellefonte was the home of John Montgomery Ward, one of the game’s first great pitchers, and Bucknell College in Lewisburg was the proving ground for Christy Mathewson. So it’s easy to imagine Myles playing on a town team or two when his farm chores were done.

And he must’ve been pretty good if Penn State coach Hugo Bezdek wanted him. In 1919, the Czech-American dynamo managed the Pittsburgh Pirates (who included Casey Stengel) to a 71–68 record, then turned around and coached the Penn State football team to a 7–1 season. (He would later become the Cleveland Rams’ first coach, thus becoming the first man to manage a club in both major-league baseball and one in the NFL.)

In 1920, Bezdek took over a Penn State baseball team that had two of his All-American football players, outfielder Hinkey Haines and second baseman Glenn Killinger. Myles, who was also known as “Tommy,” wasn’t as big on campus as they were, but that only helped prepare him for his future role in the shadows of men like Ruth and Gehrig, Hoyt and Combs.

There are no official statistics dating back that far. On May 19, 1920, though, Myles made the front page of the campus newspaper, The Collegian. Under the headline, “Thomas Pitches No-Hit Game Against Presidents,” the story about the May 12 13–0 win over Washington & Jefferson reads: “Thomas pitches a pretty game for the varsity and was the first twirler to achieve a hitless, runless victory. … The Nittany Lion moundsman was in complete control and struck out 14.”

With 10 wins to end the 1920 season, and 20 to start the 1921 campaign, the Lions won a collegiate record 30 games in a row. That brought them to the attention of scouts, one of whom was Paul Krichell of the Yankees. In the review of the 1921 season in La Vie, the Penn State yearbook, there was this nugget:

“This spring three men from our team will be trying to score berths on the New York American League team. Killinger, Haines and Thomas will all be taken South for tryouts, and if they make good, we may be hearing more about them later in the sporting world.”

As it turned out, Haines would become the first and only man ever to win both a World Series and an NFL championship: he had one at bat for the Yankees in the ’23 Series and was the star tailback of the New York Giants when they won their first NFL title in 1927. Killinger never made the majors, but he did play tailback for the Canton Bulldogs and New York Giants before becoming a highly respected college football and baseball coach. Myles, who reported to Hartford after the tryout, was the only one who would stick around in the big leagues.

As it turned out, Haines would become the first and only man ever to win both a World Series and an NFL championship: he had one at bat for the Yankees in the ’23 Series and was the star tailback of the New York Giants when they won their first NFL title in 1927. Killinger never made the majors, but he did play tailback for the Canton Bulldogs and New York Giants before becoming a highly respected college football and baseball coach. Myles, who reported to Hartford after the tryout, was the only one who would stick around in the big leagues.

On July 5, 1921, Thomas did the most amazing thing. In his very first professional game, he threw a no-hitter as Hartford beat the Springfield Hampdens, who had three ex-major leaguers: Marty Becker, John Flynn and Danny Silva, and his old friend from Happy Valley, Hinkey Haines.

In Hartford, Myles’s manager was the infamous bigamist, Arthur Irwin, and just missed being a Hartford teammate of Lou Lewis, an 18-year-old, hard-hitting first baseman from New York. That would have been Lou Gehrig, playing professionally for the Senators under an assumed name (“Lou Lewis”), so as not to jeopardize his collegiate standing. (Just a week before Myles arrived in Hartford, Lou’s true identity was discovered and he was pulled off the Hartford team by his Columbia University coach, and had to forfeit his first year of eligibility.)

Myles would go 9–13 for the Senators that season, but his ERA of 2.41 belied his record. Indeed, he was considered something of a star. In November of ’21, a writer from the Hartford Courant caught up with Myles in an article headlined, “Myles Thomas Hunting Game in Penn. Wilds”:

“The right-handed flinger… is tromping in the wilds of the northern part of Pennsylvania hunting bear… Thomas was popular with Hartford fandom, but none will miss him more than Owner Jim Clarkin, who declares he was one of the best-liked players connected with the club in his long baseball career.”

That popularity extended to a certain 22-year-old Hartford woman named Helen Belcher. They married the next year. “She must have been quite the looker,” said grandson Joe. “She was glamorous even to us.”

By then, Myles had been assigned to Reading. He had auditioned for Miller Huggins in January, but the Yankee manager didn’t think he was ready. Huggins was probably right. Thomas had an awful year with the Aces, going 2–8 with a 5.37 ERA. Still, he was one of the players featured on a souvenir pin series sponsored by Kolb’s Mother’s Bread.

One of the wonderful things about baseball is that the past often dresses with the future in the clubhouse. Playing for Reading that year was the Aces’ pitcher-manager, Chief Bender, who was in his sunset at 38 but would one day go into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Also on the staff was Al Schacht, who had mediocre stuff but a bright future as “The Clown Prince of Baseball.” The catcher was the washed-up Justin Clarke, who once hit eight homers in a game for the Corsicana Oil Citys. Oh, and the kid over there in the corner? That was Babe Herman, who eight years later would bat .393 for the Brooklyn Robins, with 35 homers and 130 RBIs.

In March of 1923, Myles’s contract was sold to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League. One newspaper article stated, “Wildness is his fault and Manager Dan Howley of Toronto thinks he can cure it.” Also known as “Howling Dan,” Howley would go on to manage the St. Louis Browns and Cincinnati Reds for three seasons apiece. And he did help Myles, who he thought was short-arming the ball.

Myles turned around his career in Canada, winning 57 games in his three seasons there. He enriched his life in Toronto, as well: Helen gave birth to a daughter, Myrtice Ann, on July 25, 1923. (Myrtice, pronounced “Mir-tiss,” was a fairly popular name at the time.)

Following the 1925 season, in which he went 28–8 with a 2.52 ERA — thanks in part to the hitting and fielding of young second baseman Charlie Gehringer — Thomas was sold to the Yankees for $25,000. According to an article in the January 6 Reading Eagle, Myles was the first Yankee to sign that year, joining three others who were already under contract: Wally Pipp, Herb Pennock, and Babe Ruth.

Thomas made his major-league debut on April 18, against the host Senators, relieving Bob Shawkey in the eighth. He kept Washington at bay until the 11th, when rookie second baseman Tony Lazzeri made an error that led to a victory for the Senators and a loss for Myles.

But that performance must’ve gotten Huggins to thinking that Thomas might make a starting pitcher. On May 14 he outdueled Dutch Levsen of the Indians over nine innings, winning 2–1 thanks to the two-run homer that the Babe hit in the first inning.

Thomas had a decent fastball, but his out pitches were a nasty curve and a forkball, the precursor to the modern changeup. Over the next month, “Duck Eye” — the name Ruth gave him because of his close-set peepers — would throw three more gems, one against the Browns and two against the Red Sox. On June 19, Thomas earned his sixth win, against the White Sox, nearly 14 percent of the first-place Yankees’ 43 victories.

But that would be his last win for the year. Huggins was notoriously mercurial when it came to selecting his pitchers, and after a few bad outings, Thomas was placed back on the shelf. He finished the regular season at 6–6 with a 4.23 ERA and three complete games.

Huggins did use him in the World Series against the Cardinals, though. In Game 3, Myles entered in the eighth inning with the Yankees trailing 4–0, gave up a single to Jim Bottomley, then got Les Bell to hit into a 6–4–3 double play and Chick Hafey to ground out to third. In Game 6, a 10–2 loss, he was asked to clean up the mess, which he did by allowing just one run in two innings of work.

In G.H. Fleming’s Murderers’ Row, an extraordinary collection of newspaper stories from the ’27 campaign, the vicissitudes of Myles’s season are revealed. He didn’t appear in a game until May 4, when he was called in to stop the bleeding after Dutch Ruether and Bob Shawkey gave up seven runs in the first inning to the Senators. Wrote Pat Robinson of the New York Telegraph: “Thomas turned in a beautiful seven innings, and Huggins again found solace in the work of a second-string pitcher.”

Huggins gave him a start in a May 23 game in Washington, and though he lost 3–2, Charles Segar of the Daily Mirror wrote, “Thomas did not pitch a bad game. Had he been given good support, he probably would have registered his first victory of the season.”

Myles’s first win in ’27 came on May 29 in Yankee Stadium. He was summoned in the third inning after Fred Haney of the Red Sox, who would later cross paths with Thomas, homered off Ruether to give Boston a 4–0 lead. The Yankees rallied to win 15–7, and Myles went the last seven innings.

He might have been the Yankees’ best pitcher in June, winning five and losing one in six starts and three relief appearances. In a 9–8 victory over the Athletics on June 28, Urban Shocker got the win and Thomas would have gotten the save had it been an official stat. But he did earn this acknowledgement from Fred Lieb of the New York Post: “The Penn Stater made quick work of the Athletic rally and got two of the toughest men on the A’s, Simmons and Cochrane.”

Shocker and Thomas were friends and roommates, but their relationship had at least one rocky moment. In Babe Ruth’s Own Book of Baseball, a breezy guide actually written by Ruth’s ghost writer, Ford Frick, the chapter on baseball superstitions contains this anecdote:

“Urban Shocker believes that throwing a hat on a bed is bad luck. He used to room with Tommy Thomas, the kid pitcher, and one night Tommy came into the room, and threw his hat on the bed. Shocker was scheduled to pitch the next day. And he was furious. The things he said to Tommy wouldn’t look good, even if printed in Yiddish. It’s a wonder Tommy came out alive. And it’s a certain cinch he has never thrown his hat on the bed since then. The following afternoon Shocker pitched a beautiful game but lost by one run.”

The Yankees also called Thomas “Professor” because, well, he looked more like a scholar than an athlete (5’9”, 170). That made made him a natural companion for Shocker, who would often study the box scores from out-of-town newspapers to try to get an edge on future opponents. (Shocker was one of the last pitchers to legally throw a spitball since he was using it before the pitch was banned prior to the 1920 season.)

After a few bad outings in July, Thomas again fell into disfavor. Huggins did give him a start on September 15 in Yankee Stadium against the Indians. He pitched fairly well, but took the 3–2 loss to fall to 7–4 on the season. Had he won, he would have gotten credit for the Yankees’ 100th victory in ’27.

He didn’t pitch in the World Series against the Pirates, but then, there wasn’t much of a chance since the Yankees swept the Series as Huggins employed only four pitchers — Wilcy Moore pitched twice. It was hard to complain, though: Myles’s World Series share came to $5,592. That, combined with the $6,500 contract he had signed, helped Myles and Helen buy a $4,000 house on Jaggard Street in Altoona, just down the road from State College.

***

There is a story, probably apocryphal, involving Myles and Ruth, who was notorious for forgetting people’s names. According to Billy Werber, a third baseman who played briefly for the Yankees before finding stardom elsewhere, Tony Lazzeri decided to play a joke at the Boston train station by introducing Myles to the Babe as a new pitcher who had just joined the ball club from Yale. Babe stuck out his hand and said, “Hi, Keed. Glad to have you on the club,” even though Myles had been on the team for a few years.

The reason that tale seems doubtful is a photograph that Joe Happer has of his mother and another child standing with the Babe during spring training. He also has a striking photo of Myrtice being held up by a smiling Adonis — Lou Gehrig. Myles was very much a part of the team, and despite his lack of work, he was still on Huggins’s mind.

Midway through the 1928 season, Huggins told a reporter that he wanted to use Thomas in the same way he had used Wilcy Moore in ’27: “I expect to use Thomas a lot from now on. He looked as though he would develop into a regular winner for us in 1926, and I haven’t weakened on him. He was quite ill early in the present season, and it took him some time to regain his full strength… Thomas is a smart pitcher, he has a good change of pace, and I still entertain a lot of hope for his future.”

The nature of Myles’s illness is a mystery. But on July 15, he recovered enough to make his only start of the season, getting his only win in a 6–4 victory over the Indians. Despite Huggins’s best intentions, the heaviest work Thomas did in ’28 was carrying Shocker’s coffin. He pitched in only 12 games and had an ERA of 3.41 in those. Once again, he sat out the World Series, a sweep of the Cardinals.

Thomas made just five appearances for the Yankees in ’29 before he was released on June 15, then the major league cut down and trade deadline day. The Washington Senators, managed by Walter Johnson, immediately signed him, and Myles found himself playing with a whole different contingent of legends: the Big Train himself, Sam Rice, Joe Cronin, and Goose Goslin.

Imagine how Myles felt when they slapped his back after beating the Red Sox 6–1 on a four-hitter on June 21. Johnson put him to good use: He pitched in 22 games, started 14 and finished 7–8 — right in line with the 71–81 Sens — with a 3.52 ERA.

But as promising as the ’29 season might have seemed to Myles and Helen, 1930 was his own Great Depression. After going 2–2 with an 8.29 ERA, he found himself pitching in Newark for the Bears and their 42-year-old player-manager, Tris Speaker.

According to the 1930 Census, Myles and Helen lived on 1308 Jaggard St. in Altoona. Also listed was his offseason occupation: mechanic in a “municipal car shop.” He had gone from The Big Train to streetcars. But that knowledge of motors would stand him in good stead.

***

He was pretty much the toast of Newark in 1931, going 18–6. He was 33, though, and no calls came in from major league teams. He and Helen and Myrtice went West in ’33, to play for the Hollywood Stars along with his old Yankees teammate Bob Meusel. “That might explain a photo they had in their house,” said grandson Tom, who became an actor. “It’s an autographed picture signed to Myles from Marion Davies, the actress who was William Randolph Hearst’s mistress.”

Myles had two decent years for St. Paul in 1933 and ’34, touching base with yet another former member of Murderers’ Row, Ben Paschal. His pitching career effectively ended with two more stops in ’35: Indianapolis and Toledo. He was on the same Mud Hens staff as Dizzy Trout and Jim Turner, who would become the longtime pitching coach of the Yankees — not to mention the nemesis of Jim Bouton in his memoir, Ball Four.

The peripatetic life of the Thomases was such that after his daughter died in 1999, her obituary read: “Myrtice attended over 20 grammar schools throughout the United States.” Each offseason, they would return to Altoona and the close-knit community on Jaggard Street.

But it was in Toledo that they finally settled. The player-manager was Fred Haney, who became a lifelong friend, as well as the manager of the 1957 Milwaukee Braves, the team that beat the Yankees in seven games of the World Series. Because Toledo was part of the Tigers’ farm system, Haney dispatched Thomas to nearby Tiffin to run their farm team in the Ohio State League, also called the Mud Hens.

He made friends easily. But what kind of guy was Myles Thomas? Well, here is a brief glimpse of his personality in a May 12, 1936 letter that Myles wrote in his capacity as general manager of the Tiffin Baseball Club, Inc. It is addressed to a Mr. Egan concerning some prospects, and his voice comes through loud and clear and delightful:

“Am writing to you in regards to this boy Bates whom we are unable to use at this time. It is not that I do not think him Class D material but our second base position is taken care of by a local boy who has been somewhat of a star here the past couple of years and to replace him would be like nailing up the entrance of the park… Of the four boys sent us from Charleston three have decided to stay but the fourth Furry a catcher left us several days ago. Either through an offer of a better job or fear of someone stealing his best girl we are not certain…”

Myles was promoted to manager of the Toledo Mud Hens in 1939 after Haney left to take over the St. Louis Browns, and Joe still has a clipping of a newspaper photo of Myles celebrating the news with Helen and Myrtice. Though there are no official American Association records from that season, the Mud Hens must have been dreadful. If you were to total the wins and losses of their pitchers, their won-lost record would come to 52–109.

Two members of the team, however, went on to play prominent roles in the World Series, for entirely different reasons. A 26-year-old outfielder named Frank Secory later worked as an umpire in four different Fall Classics.

The other one was a 19-year-old pitching prospect named Fred Hutchinson, and he would become the manager who took the Cincinnati Reds to the 1961 World Series. But in 1939 he was having control problems, and the Tigers sent him to Thomas for a cure. Just as Dan Howley had helped Myles find the plate in Toronto, Myles helped Hutchinson in Toledo. Here is how Clay Eals described the move in an article for the Society of American Baseball Research:

“The strategy eventually worked. Over the next two and a half months, Hutch went 9–9 for the last-place Mud Hens, emerging as the team’s lone American Association All-Star. He rebounded to Detroit on July 21… thus began a lengthy major league ascendance.”

You could say that the man who helped Pete Rose get to the majors was the same man whom Myles Thomas helped get to the majors.

In 1940, at the age of 42, Thomas returned to the mound to pitch 22 games for the Tiffin Mud Hens. By then, he was already onto his second career: car salesman. Eventually, he became the sales manager for Trilby Motor Sales in Toledo.

***

Myrtice, whose best friend was Fred Haney’s daughter, went to Ohio State and became a stewardess for Eastern Airlines. For a time, she dated Frankie Stranahan, a golfer known as the “Toledo Strongman.” (Stranahan, who was coached by Byron Nelson, later became Tom Watson’s mentor.)

While stationed in Miami, Myrtice met Carl Happer, a former football and baseball player for Auburn who worked for a phone company as the district traffic manager. They married and moved to Birmingham, where they had two sons, Thomas, born in 1949, and Joseph, born in 1951. “My grandfather loved that Carl was an athlete,” Joe said. “It reminded him of the days when he was one, too.”

Myles and Helen stayed in close touch with their old friends from Altoona, and joined them for summer vacations in cottages at nearby Raystown Dam. Joe, a retired information systems consultant with two adult sons and a rock cover band called “Corporate Therapy,” remembered those days well. “That community was literally built for speed,” he said. “They loved fast cars — remember the Studebaker Avanti? — and fast boats.”

Myles also maintained contact with his old teammates, especially Haney. Joe still has a ball in his Atlanta home autographed by the members of the 1957 World Champion Milwaukee Braves that Haney sent to his grandfather. “There they are,” he said, reading the names. “Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Warren Spahn, Del Crandall …”

Tom, who is retired and does volunteer work in Vermont, has the watch given to Myles for winning the 1928 World Series, while Joe has the World Series ring from 1927. In fact, he takes it out of his safety deposit box every postseason, and wears it until the day after the last out of the World Series. “Just to give it some air,” he said.

But Joe’s most treasured souvenir is a memory.

“It was a Christmas visit in ’62, the year before he died. Myles and Helen drove down to Alabama from Toledo during a blizzard — the highway patrol tried to stop him, but he told them he knew how to drive in the snow and ignored them. Anyway, they get to our home in Mountain Brook, and the sun is shining. Not knowing my grandfather was taking nitroglycerine for his heart, I asked him one day if he wanted to play catch. What 11-year-old wouldn’t want to play baseball with someone who played with Babe Ruth? And he said, ‘Hell, yes.’

“Painted on our driveway were markings for home plate and the pitcher’s mound. I stood behind home plate and he lobbed the first one in there. This was a man who hadn’t thrown in like 25 years. Then he began to get in a rhythm, and pretty soon, Whoosh. He’s not rearing back or anything, just throwing nice and easy, but these fastballs are hissing. I’m used to Little League — I never heard a ball make that sound, and I would’ve been scared, except that each pitch was right to my glove.

“He must’ve thrown a dozen of them before my Mom and Helen come out of the house to tell him to stop. He said ‘Oh, crap’ and mumbled something about wanting to throw with his grandson. But I could tell he got a kick out of it.

“Right to the end, Myles was still pitching.”

This article originally appeared at ESPN’s “The Diary of Myles Thomas,” a season-long experiment in real-time historical fiction, and is used by permission of the author. Learn more at ESPN.com/1927.

Full Name

Myles Lewis Thomas

Born

October 22, 1897 at State College, PA (USA)

Died

December 12, 1963 at Toledo, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.